Abstract

The head and face are relatively common sites of gunshot injury, and the temporomandibular joint is often affected. These wounds usually produce major deformity and functional impairment, particularly when the temporomandibular joint is affected or when structures such as the facial nerve are damaged. Complications may include mandibular displacement at maximum mouth opening and in protrusion, limited mouth opening, limited lateral movement of the jaw, anterior open bite, and, more rarely, temporomandibular ankylosis. Projectiles that strike the mandible usually cause comminuted fractures; maxillary wounds, in turn, are most commonly perforating. The present report describes a case of gunshot injury in which the projectile lodged within the mandibular fossa but did not cause any fractures. Oral and maxillofacial trauma surgeons must be aware of the different types of gunshot injury, as they produce distinct patterns of tissue destruction due to projectile trajectory and release of kinetic energy into surrounding tissue.

The head and face area is a relatively common site of gunshot injury.[1] The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) may be involved in many cases, as may important anatomic structures such as the facial nerve,[2] with the potential for development of traumatic facial palsy.[3] Lesions of the temporal and marginal branches produce remarkable functional loss and must be repaired. Immediate reconstruction is indicated in cases of uncontaminated trauma. However, in FAF, the posterior repair is reserved due to contamination of the injury, although the nerve terminations must be identified and repaired for anastomosis.[3]

The pattern of trauma in gunshot wounds (GSWs) is extremely variable. These injuries may affect vital structures and cause difficult-to-control bleeding, and proper initial management usually requires a multidisciplinary approach. GSWs often cause comminuted fractures with multiple small bone fragments[1,4] and may produce sequelae as serious as those caused by massive blunt impact to the same area.

This report seeks to present an atypical case of facial gunshot injury in which the projectile was found to be lodged within the mandibular fossa without any evidence of bone fracture.

Case Report

A 32-year-old male was referred to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery service of our institution three days after being shot with a low speed 0.38-caliber revolver. The patient explained the late demand for treatment because he didn’t want to get caught by the police, however, the bad evolution of the case forced him to seek treatment.

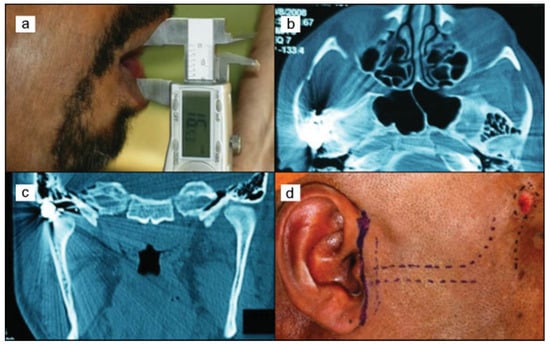

On primary survey, the patient was hemodynamically stable, with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 15, patent airway, and no active bleeding. There was massive right-sided hemifacial edema, with limited mouth opening (16 mm) (Figure 1a), occlusal abnormality and pain.

Figure 1.

(a) Preoperative aspect: limited mouth opening (16 mm); (b) axial CT showing projectile lodged within the mandibular fossa; (c) coronal CT; (d) bullet trajectory.

Computed tomography showed an entrance wound near the zygomaticofrontal suture (Figure 1b–d) and a retained projectile within the right mandibular fossa, with no discernible fractures. An angiography was not performed because unfortunately, in our regional hospital, we don’t have such equipment.

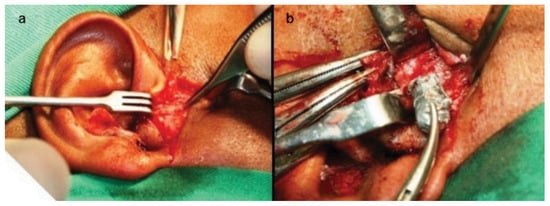

The decision was made to extract the projectile via the preauricular approach (Figure 2a), as described by Ellis III & Zide (2006),[5] as it was limiting mandibular movement. The projectile was removed from the TMJ (Figure 2b and Figure 3a), the wound was rinsed copiously with saline solution (NaCl 0.9%), and the entrance site was debrided for removal of bone splinters and casing fragments.

Figure 2.

(a) Pre-auricular approach; (b) projectile extraction.

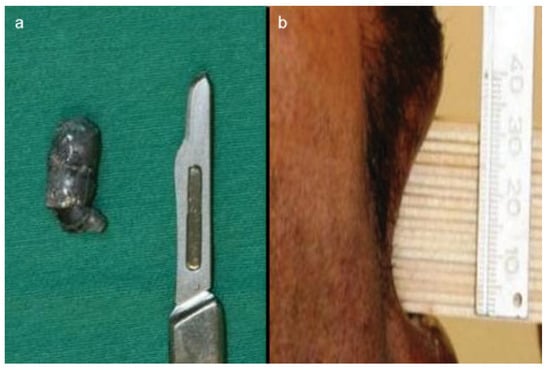

Figure 3.

(a) Projectile size; (b) normal mouth opening (32 mm) at 20-day follow-up.

The patient was discharged in good condition on the fourth postoperative day, with mild edema in the right lower quadrant of the face and limited mouth opening. There was no facial nerve palsy. At 20-day follow-up, the patient had normal mouth opening (32 mm) (Figure 3b), despite non-adherence to the prescribed orofacial myofunctional therapy regimen. He was pain-free and had recovered full stomatognathic system function. Unfortunately, the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Discussion

GSW-related trauma to the TMJ region is associated with transfer of a massive amount of kinetic energy to the injured area, which may cause damage to local anatomic structures such as bone and cartilage. This damage, in turn, may lead to such complications as edema, limited mouth opening, and TMJ ankylosis.[1]

Gunshot wounds may be classified as penetrating, perforating, or avulsive. In penetrating injuries, such as that described herein, the projectile remains lodged in the injured tissue. Low-velocity gunshot wounds are generally penetrating. In perforating injuries, which are characteristic of high-velocity projectiles, there is an entrance wound and an exit wound. Avulsive gunshot wounds are those involving loss of tissue, and are usually caused by high-velocity or ultrahigh-velocity projectiles, or even by shrapnel.[6,7,8]

Initial care of patients presenting with a GSW to the face should focus on the ABCs, with particular emphasis on the airway component, as bleeding from the wound and subsequent edema may lead to significant airway compromise.[9,10]

Cases in which the projectile traverses the aerodigestive tract or the paranasal sinus are particularly hazardous. Devitalized tissue and vascular congestion provide an optimal environment conducive to bacterial growth.[11] To decrease morbidity, debridement should be kept to a minimum.[12,13] Extensive surgical debridement of injuries consistent with a low-velocity projectile is rarely indicated, so as to reduce the risk of infection.[11] All GSW victims should receive broad-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis, usually with a second-generation cephalosporin, and tetanus prophylaxis as indicated.[12]

The management of facial GSWs has led to much advancement in the knowledge and development of oral and maxillofacial surgery techniques, and remains the object of extensive discussion.[14]

Nevertheless, management of these injuries is still somewhat beset by a dogma that has persisted since the earliest days of trauma surgery and is still inculcated in the minds of some practitioners during training: the decision to delay definitive treatment. This practice is based on the misguided belief that tissue devitalization and infection are inevitable after gunshot injury.[15]

Shinohara (1999)[9] recommends that, once the decision has been made to pursue surgical treatment, initial measures should consist of copious irrigation with saline solution, wound debridement, and extraction of bone sequesters, dental fragments and foreign bodies. The projectile itself should only be removed if it is near the surface or causing functional impairment; otherwise, it is left embedded in situ. This method is consistent with our opinion.

Ogata et al (2003)[16] advocate the following protocol for GSW care: immediate surgical debridement; antibiotic therapy; careful attention to soft tissue injury and judicious layered closure, for better cosmetic results; orthodontic banding to restore the balance of forces, as major muscle tissue loss will lead to spasms and potential mandibular displacement; referral for physical therapy and speech– language pathology care as indicated, so as to restore stomatognathic system function as soon as possible; and, in most cases, delayed reconstruction, using appropriate criteria for sequelae of traumatic injury, orthognathic repair or graft reconstruction.

Not all GSWs are managed surgically. Transfixing (“through-and-through”) injuries not causing fracture or vascular injury do not require surgical intervention. In these cases, urgent care focuses on wound cleanup, conservative debridement and closure.[17] Projectile extraction surgery is only indicated if the retained projectile is close to the surface or is hindering normal movement of adjacent structures, as in our patient.

Gunshot wounds to the temporomandibular joint area are severe and may be associated with a variety of sequelae, such as edema and limited mouth opening, as reported herein. We disagree with the assertion that edema lasts 7 days (Cunningham et al, 2003),[18] as, in our experience, said edema may persist for several weeks postoperatively.

Conclusion

Growing levels of urban violence have led to an increase in the number of patients presenting to hospitals with gunshot wounds. Health care professionals must therefore be ready to deliver better care to these patients so as to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Immediate, definitive treatment of mandibular gunshot wounds should be the goal whenever patient and setting permit, as they enable reintegration of patients into society as quickly as possible and thus mitigate the socioeconomic impact of these injuries.

References

- Pereira, C.C.S.; Jacob, R.J.; Takahashi, A.; Shinohara, E.H. Mandibular fracture by projectile from a firearm. Rev Cir Traumatol Bucomaxilofac 2006, 6, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- He, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ellis, E., III. Panfacial fractures: analysis of 33 cases treated late. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007, 65, 2459–2465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pinna, B.R.; Testa, J.R.G.; Fukuda, Y. Estudo de paralisias faciais traumáticas: análise de casos clínicos e cirúrgicos. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed) 2004, 70, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariades, N.; Mezitis, M.; Mourouzis, C.; Papadakis, D.; Spanou, A. Fractures of the mandibular condyle: a review of 466 cases. Literature review, reflections on treatment and proposals. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2006, 34, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, E., III; Zide, M. Acessos cirúrgicos ao esqueleto facial, 2nd ed.; Santos: São Paulo, 2006; pp. 193–199. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, D.B.; Bays, R.A. Pathophysiology and management of gunshot wounds to the face. In Oral Maxillofacial trauma; Fonseca, R.W., Ed.; Saunders Co: Philadelphia, 1991; pp. 672–701. [Google Scholar]

- Akhlaghi, F.; Aframian-Farnad, F. Management of maxillofacial injuries in the Iran-Iraq War. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997, 55, 927–930, discussion 930–931. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pena, E.O.; Marzola, C.; Campos, C.R.N.; Toledo Filho, J.L.; Zorzetto, D.L.G.; Pastori, C.M. Tratamento de lesões faciais causadas por armas de fogo – Considerações gerais e apresentação de casos cirúrgicos. Rev Ass Maringaense Odont 2000, 1, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara, E.H.; Shigeto, E.B.; Mitsuda, S.T.; Carvalho Júnior, J.P. Tratamento de fratura mandibular por projétil de arma de fogo. Rev Assoc Paul Cir Dent; Escola de Aperfeiçoamento Profissional: São Paulo, 1999; pp. 363–365. [Google Scholar]

- Hollier, L.; Grantcharova, E.P.; Kattash, M. Facial gunshot wounds: a 4-year experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001, 59, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holmes, J.D. Decker, B.C., Ed.; Gunshot injuries. In Peterson’s principles of oral and maxillofacial surgery, 2nd ed.; B.C. Decker, 2004; pp. 509–524. [Google Scholar]

- Alper, M.; Totan, S.; Cankayali, R.; Songür, E. Gunshot wounds of the face in attempted suicide patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998, 56, 930–933, discussion 933–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motamedi, M.H. Primary management of maxillofacial hard and soft tissue gunshot and shrapnel injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003, 61, 1390–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, L.J.; Ellis, E.E.; Hupp, J.R.; Tucker, M.R. Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery, 3nd edMosby: Saint Louis, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, H. A history of surgery; Greenwich Medical Media Limited: London, 2001; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata, E.; Ono, H.Y.; Leandro, L.F.L. Fraturas mandibulares por projétil de arma de fogo. Rev Internacional de Cirurgia e Traumatologia Bucomaxilofacial; Dental Tribune International: Curitiba, 2003; pp. 212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Demetriades, D.; Chahwan, S.; Gomez, H.; Falabella, A.; Velmahos, G.; Yamashita, D. Initial evaluation and management of gunshot wounds to the face. J Trauma 1998, 45, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, L.L.; Haug, R.H.; Ford, J. Firearm injuries to the maxillofacial region: an overview of current thoughts regarding demographics, pathophysiology, and management. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003, 61, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2014 by the author. The Author(s) 2014.