Abstract

The social, financial, and health implications of adult alcohol-related oral and maxillofacial trauma have been recognized for several years. Affordability and widespread accessibility of alcohol and issues of misuse in the pediatric trauma population have fostered concerns alcohol may be similarly implicated in young patients with orofacial trauma. The aim of this study was to review data of pediatric facial injuries at a regional maxillofacial unit, assess the prevalence of alcohol use, and review data of patients sustaining injury secondary to interpersonal violence. This study is a retrospective, 3-year review of a Regional Maxillofacial Unit (RMU) trauma database. Inclusion criterion was consecutive facial trauma patients under 16 years of age, referred to RMU for further assessment and/or management. Alcohol use and injuries sustained were reviewed. Of 1,192 pediatric facial trauma patients, 35 (2.9%) were associated with alcohol intake. A total of 145 (12.2%) alleged assault as the mechanism of injury, with older (12–15 years) (n = 129; 88.9%), male (n = 124; 85.5%) (p < 0.001) patients commonly involved and alcohol use implicated in 26 (17.9%) presentations. A proportion of vulnerable adolescents misuse alcohol to the risk of traumatic facial injury, and prospective research to accurately determine any role of alcohol in the pediatric trauma population is essential.

The affordability, accessibility, and widespread misuse of alcohol are current issues of national concern. In recent years, it has been alleged that marketing of some alcoholic drinks, to attract young adults, encourages excessive consumption in children and adolescents[1] and the effects of alcohol in this age group are now a serious public health and financial burden.

Adolescence is a period of development associated with independence from parents and participation in risk behavior including alcohol experimentation. The additional influence of young adult role models can further promote childhood exposure to alcohol misuse and these combinations of factors may predispose young people to traumatic injuries requiring hospitalization.[2]

Trauma remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children worldwide, surpassing all major diseases of children, and can be associated with lifelong disability. Head injuries remain the most prevalent, yet severe pediatric maxillofacial trauma is still moderate compared with adults.[3]

Alcohol is a recognized risk factor in the adult trauma population[4] and the role of alcohol in adult maxillofacial trauma, particularly as a consequence of interpersonal violence, is well established.[5,6,7] Little research exists on the prevalence and any role alcohol may have in the pediatric trauma population.[2,8] In cases of pediatric maxillofacial injuries, studies recognizing alcohol involvement are few,[9,10] and in relation to the etiology and epidemiology of pediatric facial trauma, the presence and possible role of alcohol remains largely unknown.

The global public health challenge of pediatric trauma documented current trends of adolescent alcohol misuse, and the recognition of the role of alcohol in violent-related adult maxillofacial trauma implies that work to evaluate and assess the prevalence and possible role of alcohol in cases of pediatric facial trauma is essential.

The aim of this study was to review etiological, epidemiological, and geographical data of pediatric facial injuries presenting to a busy urban regional maxillofacial unit over a 3-year period, assess the prevalence of alcohol involvement in these cases, and consider any contributory role alcohol may have in pediatric maxillofacial trauma presentation, particularly in cases whereby the mechanism of injury was interpersonal conflict.

Materials and Methods

The study involved retrospective review of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (OMFS) database of 9,459 consecutive adult and pediatric patients presenting or referred to a busy urban Regional Maxillofacial Unit (RMU) in the United Kingdom over a 3-year period.

Standardized trauma data forms, completed by OMFS staff at the time of presentation, were logged in a secure electronic database. Data, which included information on patient age, sex, mechanism of injury, location where injury occurred, injury sustained, and presence of alcohol, were recorded.

Inclusion criterion was all consecutive pediatric facial trauma patients under 16 years of age, referred to OMFS for further assessment and/or management within the set 3-year period of review.

The presence of alcohol, admitted by the patient on direct questioning or deemed likely in the context of clinical examination, was included. Data were analyzed according to mechanism of injury with alcohol use for these documented when applicable. Patients sustaining injuries secondary to alleged acts of interpersonal violence were further investigated to identify gender, age range, and geographical location where the injury occurred. Of those cases citing alleged assault as the mechanism of trauma, the oral maxillofacial and/or head injury sustained was additionally reviewed.

All referrals from local accident and emergency departments, general practitioners, and general dental practitioners were included in this study. All sections of trauma data forms were successfully completed in approximately 95% of those reviewed.

Results

Over the 3-year period of review, 1,438 (15.2%) pediatric (under 16 years of age) patients presented to the RMU with maxillofacial emergencies. Of these, 1,192 (82.9%) presented following trauma and 246 (17.1%) with acute illness such as craniomaxillofacial infection.

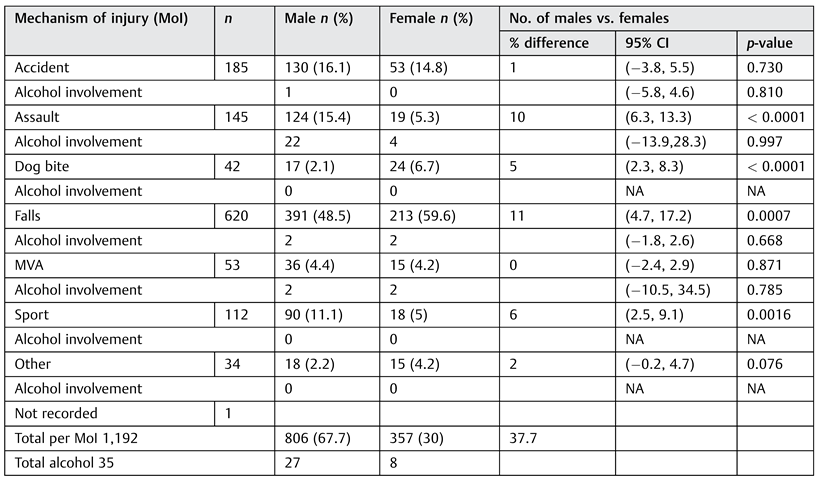

Of 1,192 trauma patients recorded, 35 (2.9%) were positive for alcohol involvement, with a male (n = 27) to female (n = 8) ratio of 3.4: 1. Of the remaining 1,157 pediatric patients, no use of alcohol was documented. The ratio of pediatric trauma male (n = 806; 67.7%) to female (n = 357; 30%) patients was 2.3:1. Twenty-nine (2.4%) pediatric trauma patients had no sex recorded. Mechanism of injury is represented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mechanism of injury.

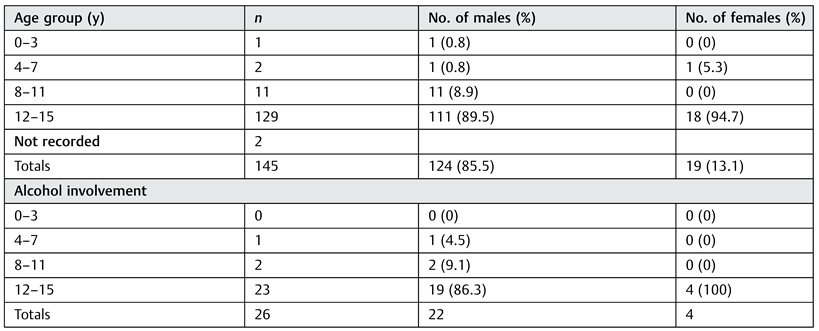

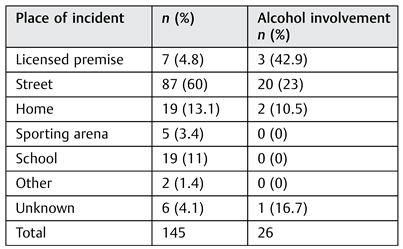

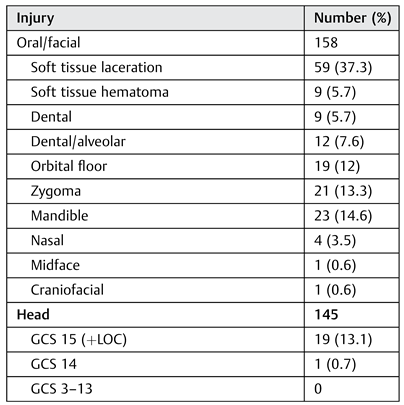

In cases of alleged assault (n = 145; 12.2%), alcohol involvement was present in 26 (17.9%) pediatric presentations, with more males (n = 22) affected than females (n = 4). Alcohol use and alleged assault as the mechanism of injury was not regarded as statistically significant (p > 0.0001). Age range, gender, and documented alcohol use of patients presenting with facial trauma secondary to an alleged act of violence are documented in Table 2. As observed, male patients aged 12 to 15 years (n = 111) presented most frequently and of these 19 (17.1%) had consumed alcohol prior to injury. Location of alleged assaults on pediatric patients, including information on alcohol use at the time of injury, is detailed in Table 3. Alleged assaults in the street and other unspecified outdoor areas (e.g., parks) were most frequently observed (n = 87; 60%), and of these, 20 (23%) were known to be associated with alcohol intake. Facial injuries sustained in cases of alleged interpersonal violence, including associated head injury if applicable, are illustrated in Table 4. In some instances, multiple injuries have been recorded in individual patients. Accompanying head injury, documented Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of less than 15 or GCS equal to 15 with convincing history of loss of consciousness (LOC), was included. Information regarding GCS and LOC was documented in all but two pediatric facial trauma patients following assault.

Table 2.

Pediatric facial trauma secondary to alleged assault (n = 145)—age and sex of patient.

Table 3.

Pediatric facial trauma secondary to alleged assault (n = 145)—locale of incident occurrence and presence of alcohol.

Table 4.

Pediatric facial trauma secondary to alleged assault (n = 145)—facial injuries and associated head injury.

Local deprivation scoring, based on English Indices of Deprivation 2010 (ID 2010) and Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI), was calculated for areas where pediatric facial trauma secondary to interpersonal violence (n = 145) occurred. A total of 119 (82.1%) towns, postcodes, and areas were recorded, identified, and subsequently reviewed to identify if any were associated with the highest levels of national deprivation (0–1% of 32,482 Lower Super Output Areas [LSOA] in England), with lower ranked areas accepted as most deprived. Twenty-two (15.2%) presentations of facial trauma secondary to alleged assault were associated with the most deprived LSOAs nationally, nine (34.6%) of which were associated with alcohol use.

Discussion

The perception that the prevalence of adult alcohol misuse and alcohol-associated traumatic injuries secondary to interpersonal violence may be currently reflected in the pediatric trauma population is a public health concern.

The paucity of existing research of alcohol misuse in the general pediatric trauma population ensures any contributory role of alcohol remains largely unknown.[11] In children presenting with orofacial injuries, literature on alcohol prevalence is similarly dearth, with a recent nationwide survey suggesting this to be ~5%.[9] Alcohol use in our sample population was lower (n = 35; 2.9%), and in injuries as a consequence of alleged assault, alcohol was not recognized as a significant factor (p > 0.0001). Nevertheless, the implication that a proportion of children under 16 years of age may be involved in alcohol-related violence raises concerns of the use and effects of alcohol intake in adolescents. Initiation and fostering of excessive consumption during transition to early adulthood with possible predisposition to dependence and/or alcohol-associated antisocial behaviors is of social, financial, and public health interest.

Unintentional etiology, most frequently a fall, was the most common mechanism of facial injury in the pediatric population reviewed, a finding consistent with similar reviewed literature.[3,9,10,12,13,14]

Oral and maxillofacial injury secondary to violent etiology (n = 145; 12.2%) was the third most common mechanism of injury. Published data on pediatric maxillofacial trauma as a consequence of interpersonal violence[3,9,10,12,13,14] are limited and variable, with reported incidences in western communities ranging between 3.9[3] to 16.6%,[12] increasing to 42.5%[14] in areas affected by conflict and poverty. Widespread perception that levels of assault-related pediatric facial injuries are mirroring the adult population and increasing has been refuted[12] and endorsed[15] in conflicting literature. Irrespective of prevalence or current trend, pediatric facial trauma secondary to acts of violence exists in sufficient numbers to cause concern.

In keeping with other studies,[3,9,10,12,13,14,15,16,17] male patients presented most frequently with traumatic oral and maxillofacial injuries sustained through interpersonal violence, with or without the presence of alcohol, with gender regarded as statistically significant (p < 0.0001). In studies including 16- and 17-year-olds,[16,17] increased incidences were reported, supporting suggestions that traumatic pediatric facial injuries secondary to acts of interpersonal violence increase with age into early adulthood.[3,12,16,17] The likelihood that adolescent antisocial behaviors propagate into adult life is therefore pertinent.

Importantly, alcohol misuse in the context of known socioeconomic deprivation in pediatric facial trauma presentation may be linked with the role of alcohol recognized as part of a wider milieu of deprivation-associated social influences.[9,10]

Local deprivation scoring, based on ID 2010[18] and IDACI,[19] utilizes economic, social, employment, health, and housing indicators to compare levels of LSOA deprivation (1–32,482) in England, with those ranked lowest (0–1%) accepted as most deprived. Persistently, high levels of deprivation exist in the urban area of review with one local authority ranked as the most deprived area in England.[18] Of assault-related pediatric facial injuries in this study, 22 (15.2%) patients were from the LSOA recognized as the most socioeconomically deprived in England. Of those, nine had consumed alcohol at the time of injury.

Therefore, the influence of socioeconomic deprivation in pediatric facial trauma discussed in previous studies[9] is supported by the findings of this study.

Accepted socioeconomic influences in pediatric facial trauma presentation and prevalence must be recognized when reviewing data from such areas of established deprivation, with the exact role of alcohol alone difficult to distinguish.

In addition to linked social issues of alcohol misuse and socioeconomic deprivation, lack of parental guidance, poor family support, structure, and functioning have previously been implicated in traumatic dental injuries.[20] In our data review, traumatic pediatric facial injuries secondary to assault were most commonly sustained in the street (n = 87; 60%) with alcohol intake associated in almost one-quarter (n = 20; 23%) of these cases (Table 3). These findings may represent an insufficient level of parental supervision and control which may be a contributing social factor to injuries in these children.

The absence of comparable studies inhibits interpretation of the injuries sustained (Table 4) in the pediatric trauma population presenting following intentional injury. Nevertheless, inflicted deliberate force sufficient to cause pediatric facial fracture or head injury irrespective of prevalence is alarming.

There are several limitations of this study. The retrospective approach to data review predisposes to inherent bias which must be considered in relation to findings presented. The collated data are representative of a single urban trauma population over a 3-year period. As alluded to previously, the complex mix of socioeconomic and cultural factors likely associated with pediatric maxillofacial trauma ensures direct comparison between this and similar trauma populations is not possible. The possibility of an adult perpetrator or nonaccidental injury in cases of interpersonal violence is not considered. Therefore, possibly not all pediatric facial trauma secondary to alleged assault have been inflicted by a fellow minor. An unknown number of patients with orofacial trauma will not have presented or been referred to the RMU and therefore not included in this trauma review. Finally, missing and incomplete data, an intrinsic limitation of database compilation and review, must be recognized.

Conclusion

The exact contribution of alcohol misuse in the pediatric population presenting with traumatic facial injuries is unknown. Alcohol is an intrinsic component of epidemiological and socioeconomic deprivation elements which predispose adolescents to traumatic facial injury,[9] including those sustained secondary to interpersonal violence. The concern that a proportion of vulnerable adolescents misuse alcohol to the risk of traumatic injury and are involved in alcohol-related violent antisocial behaviors must stimulate further research. Serious pediatric facial trauma secondary to interpersonal conflict, irrespective of alcohol use, is an additional concern. The welfare and future of vulnerable pediatric patients, particularly those from areas of recognized socioeconomic deprivation who may be subjected to violent conflict, must be considered a healthcare priority. A trauma center prospective study using universal screening aids to define the true impact and effect of alcohol consumption in the pediatric trauma population, particularly those injured as a consequence of violence, is the responsibility of future, essential studies.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Nunez-Smith, M.; Wolf, E.; Huang, H.M.; et al. Media exposure and tobacco, illicit drugs, and alcohol use among children and adolescents: a systematic review. Subst Abus 2010, 31(3), 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noffsinger, D.L.; Cooley, J. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment in the adolescent trauma population: examining barriers to implementation. J Trauma Nurs 2012, 19(3), 148–151, quiz 152–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassner, R.; Tuli, T.; Hächl, O.; Moreira, R.; Ulmer, H. Craniomaxillofacial trauma in children: a review of 3,385 cases with 6,060 injuries in 10 years. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004, 62(4), 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blondell, R.D.; Dodds, H.N.; Looney, S.W.; et al. Toxicology screening results: injury associations among hospitalized trauma patients. J Trauma 2005, 58(3), 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Warburton, A.L.; Shepherd, J.P. Alcohol-related violence and the role of oral and maxillofacial surgeons in multi-agency prevention. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002, 31(6), 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchison, I.L.; Magennis, P.; Shepherd, J.P.; Brown, A.E. British Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. The BAOMS United Kingdom survey of facial injuries part 1: aetiology and the association with alcohol consumption. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998, 36(1), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, D.I.; McMahon, A.D.; Graham, L.; et al. The scar on the face of Scotland: deprivation and alcohol-related facial injuries in Scotland. J Trauma 2010, 68(3), 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, K.; Charyk-Stewart, T.; Girotti, M.J.; Parry, N. Substance Use in Paediatric Trauma: Setting the Stage for an Injury Prevention Programme. Inj Prev 2010, 16(1), A85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhouma, O.; McMahon, A.D.; Conway, D.I.; Armstrong, M.; Welbury, R.; Goodall, C. Facial injuries in Scotland 2001-2009: epidemiological and sociodemographic determinants. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013, 51(3), 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, K.O.; Oliveira Filho, P.M.; Ferreira, E.F.; Oliveira, A.C.; Vale, M.P.; Zarzar, P.M. Prevalence and association of dental injuries with socioeconomic conditions and alcohol/drug use in adolescents between 15 and 19 years of age. Dent Traumatol 2012, 28(2), 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, K.L.; Vogt, K.N.; Girotti, M.J.; Stewart, T.C.; Parry, N.G. Drug use and screening in pediatric trauma. Ther Drug Monit 2011, 33(4), 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotecha, S.; Scannell, J.; Monaghan, A.; Williams, R.W. A four year retrospective study of 1,062 patients presenting with maxillofacial emergencies at a specialist paediatric hospital. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008, 46(4), 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerfowski, M.; Bremerich, A. Facial trauma in children and adolescents. Clin Oral Investig 1998, 2(3), 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcenes, W.; al Beiruti, N.; Tayfour, D.; Issa, S. Epidemiology of traumatic injuries to the permanent incisors of 9-12-year-old schoolchildren in Damascus, Syria. Endod Dent Traumatol 1999, 15(3), 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traebert, J.; Peres, M.A.; Blank, V.; Böell, R.daS.; Pietruza, J.A. Prevalence of traumatic dental injury and associated factors among 12-year-old school children in Florianópolis, Brazil. Dent Traumatol 2003, 19(1), 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, Z.S.; Worrall, S.F. Epidemiology of facial trauma in a sample of patients aged 1-18 years. Injury 2002, 33(8), 669–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaare, A.B.; Jacobsen, I. Etiological factors related to dental injuries in Norwegians aged 7-18 years. Dent Traumatol 2003, 19(6), 304–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- The Index of Multiple Deprivation 2010. A Liverpool Analysis. Liverpool City Council 2011. Accessed January 2013. Available at: www.liverpool.gov.uk/ council/key-statistics-and-data/indices-of-deprivation.

- The Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI). Accessed January 2013. Available at: www.education.gov.uk.

- Nicolau, B.; Marcenes, W.; Sheiham, A. The relationship between traumatic dental injuries and adolescents’ development along the life course. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003, 31(4), 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2014 by the author. The Author(s) 2014.