Delayed infection is thought by many to be the most serious complication following cranioplasty [

1] and can present a significant challenge to the reconstructive surgeon. To fully address complications associated with infection, it is necessary to undergo aggressive, often radical, operative debridement with the removal of all nonviable tissue, debris, and foreign materials [

1]. This debridement often leaves patients with large defects and little protection for the brain. Few options for coverage of these defects have been published in the literature. Deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flaps are popularly used for breast reconstruction [

2]; however, the use of the DIEP flap for the reconstruction of head and neck defects has recently gained support [

3,

4,

5]. While the defects in these published reports resulted mostly from cancer extirpation [

3,

4,

5], the potential exists for use in the reconstruction of defects as a result of other causes, including traumatic injury. A review of the current literature revealed no reports of the use of DIEP free tissue transfer for coverage of cranial defects after removal of infected cranioplasty hardware.

Case Report

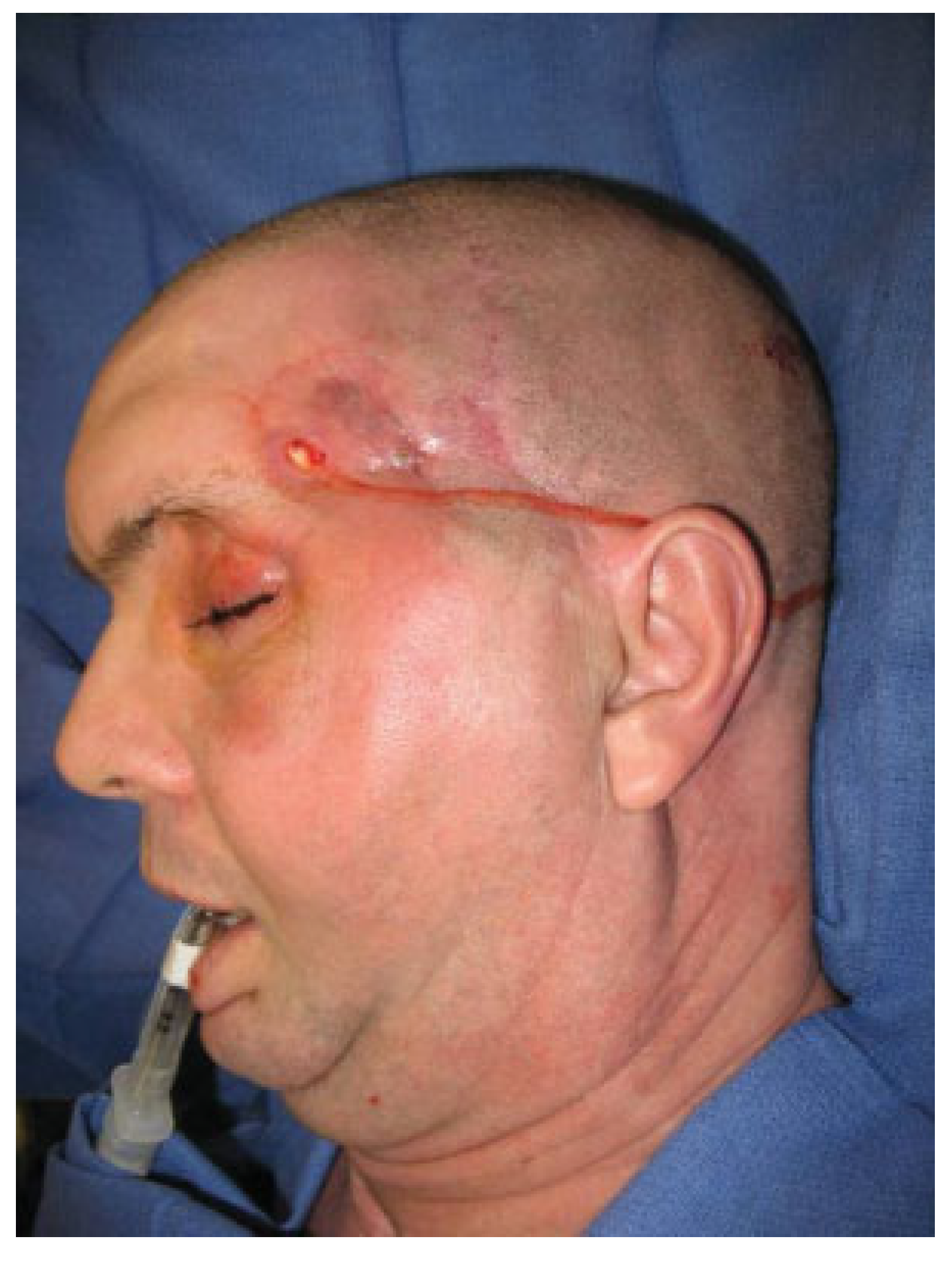

A 53-year-old man presented with several draining scalp wounds 6 years after a motor vehicle crash that resulted in severe craniomaxillofacial injury (

Figure 1). The patient had undergone multiple reconstructive operations after the accident. The draining had been going on “for a while” and it significantly impacted his daily living. Clinical examination revealed left-sided facial asymmetry and bilateral temporal hollowing with multiple open wounds over the temporal areas and vertex of the scalp with purulent drainage (

Figure 2). Preoperative craniomaxillofacial computed tomographic scan showed extensive implanted hardware and methylmethacrylate overlay.

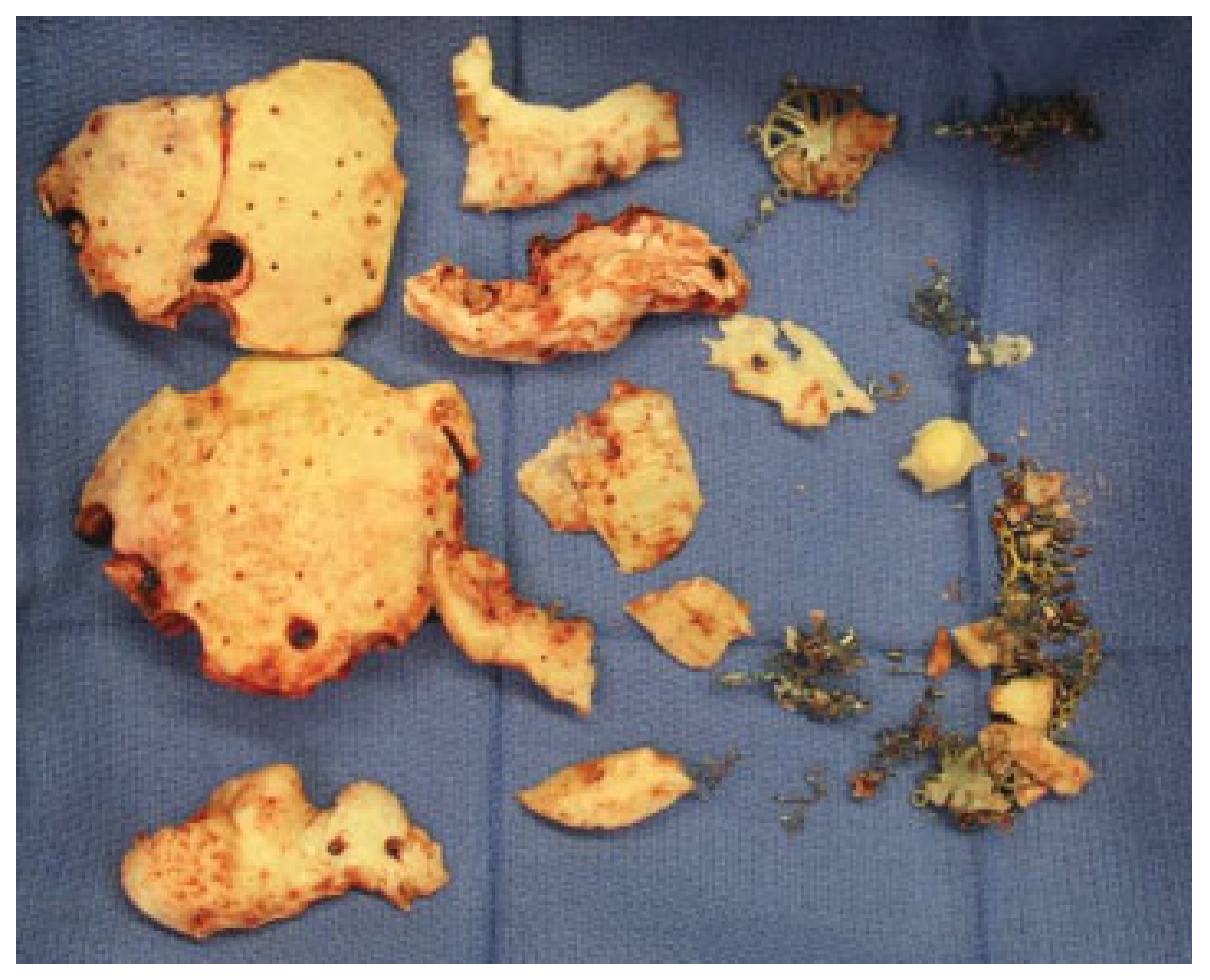

The patient was taken to the operating room for a planned, two-stage reconstruction. In the first operation, radical debridement of the scalp and calvarial wounds was completed with removal of the methyl methacrylate, underlying hardware, including titanium mesh, and any nonviable bone (

Figure 3 and

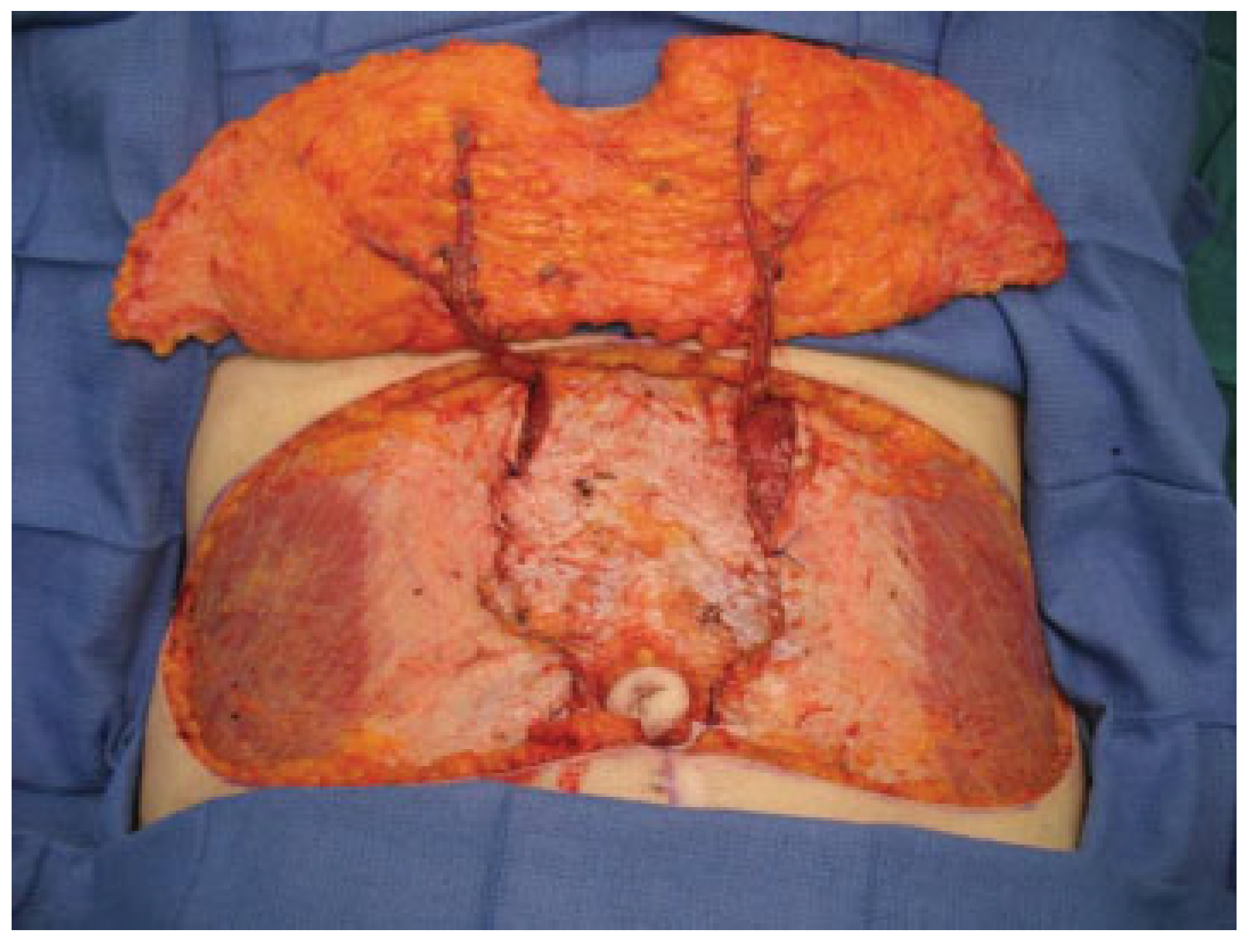

Figure 4). A bilateral, bipedicled DIEP free flap was fashioned over the defect with bilateral anastomoses performed to the superficial temporal vessels (

Figure 5). His postoperative course was uneventful (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) and donor morbidity was minimal (

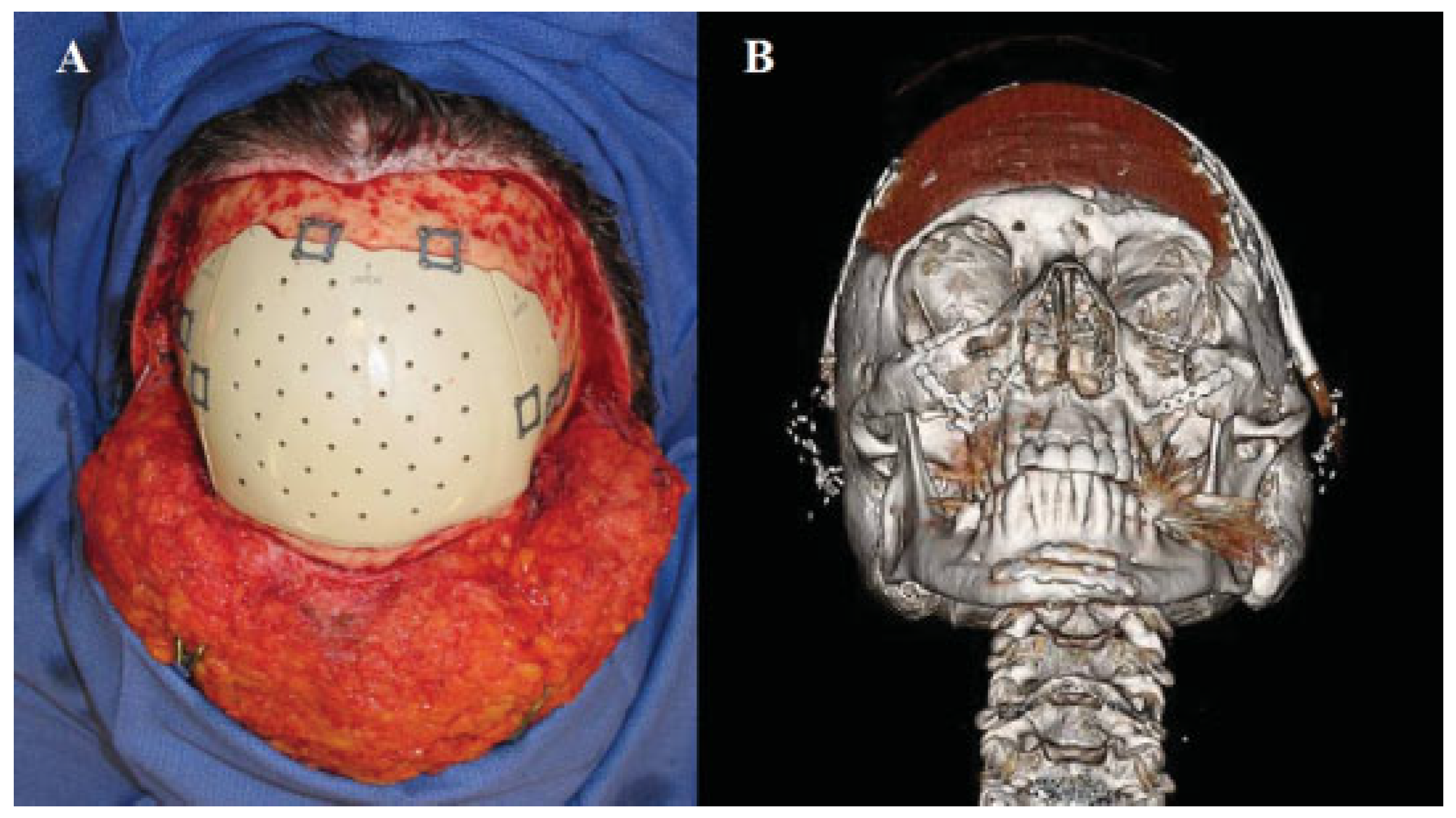

Figure 8). The patient completed a several month course of culture-specific IV antibiotic therapy to clear his indolent, chronic infection, and was brought back to the operating room 7 months later for the second stage of the procedure. Using imaging of the defect, a computer-aided designed, prefabricated polyetheretherketone (PEEK) cranioplasty was placed into the area of the bony defect (

Figure 9) and the flap was revised and reinset. The surgical incisions healed well without further drainage providing an acceptable esthetic and functional result (

Figure 10).

Discussion

For over 30 years, methyl methacrylate has been available as an option for cranioplasty when autogenous bone is not available [

6]. The material has good tension and compression stress resistance, it is inexpensive, easily molded, and provides rigidity [

6]. As the material allows for no tissue integration, methyl methacrylate can also be removed easily if it becomes infected [

6]. Common complications after a cranioplasty include chronic pain, infection, hematoma formation, scalp erosion with exposure of hardware, and migration of implants [

7]. A recent review of 70 consecutive patients undergoing polymethyl methacrylate cranioplasty revealed an infection rate of 13% [

7]. Higher infection rates have been seen in implants placed in sites with previously infected acrylic implants [

7].

Removal of infected cranioplasty implants often leaves patients with a need for some type of cranial coverage. In our case, we present the use of a bilateral, bipedicled DIEP flap for both temporary coverage during a several month antibiotic course of treatment of infection and also permanent reconstruction of the soft tissue defect over the newly placed PEEK cranioplasty implant. DIEP flaps have been an option for reconstructive surgeons since the late 1980s when they were described by Koshima and Soeda [

3]. The ability to harvest the flap with minimal stress to the muscles of the abdominal wall allows theoretically for less morbidity at the donor site and quicker recovery time,3,8 while still providing a large amount of skin and soft tissue [

2]. Although multiple alternatives for soft tissue coverage exist including: latissimus dorsi, muscle-sparing free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous, and unilateral DIEP flap there were several factors that lead to selecting a bilateral, bipedicled DIEP flap. The adipocutaneous tissue harvested with the flap allows the DIEP flap to maintain its shape and volume [

5]. This flap also allows for a two-team approach providing for simultaneous wound debridement and flap harvest to keep operative and anesthetic times as short as possible for such a complicated and complex reconstructive microsurgical case. The latissimus dorsi was abandoned due to shoulder girdle musculoskeletal impairments and chronic back pain as a result of the patient’s motor vehicle accident. Utilizing the bilateral, bipedicled DIEP flap provides the necessary bulk to protect exposed brain, ensures a rich vascular supply for a chronically infected wound, and affords more symmetric tissue to optimize cosmesis, especially for future secondary revision procedures that may be needed.

Coverage with the DIEP flap allowed the patient in this case critical, vascularized cranial coverage during an extended course of intravenous antibiotics. The ability to provide the patient with a period of time with the absence of any foreign bodies at the infection site was essential to adequate infection control and treatment. With the infection cleared, the bilateral, bipedicled DIEP flap was able to be revised and reinset to provide soft tissue coverage over the new PEEK cranioplasty implant.

Conclusion

Minimal donor site morbidity and tremendous versatility make the DIEP flap a good option in the reconstruction of cranial defects following the removal of infected hardware. The coverage it provides is extremely useful in providing cranial protection while the site of infection is treated and contributes, along with necessary cranial hardware, to an overall acceptable cosmetic result for durable and hopefully long lasting reconstruction.