Lip and/or cheek adhesion to the alveolar mucosa with subsequent loss of vestibular depth and width is a devastating problem to the patient [

1]. It usually occurs due to primary inadequate vestibular soft tissue repair following complicated trauma cases, burns, cysts, and tumors of the oral cavity. The consequences of such resultant complete or partial vestibular loss include; continuous saliva drooling, impaired mastication, and compromised speech [

2,

3].

For years, the management protocol of such cases has been composed of aggressive surgical excision of all scarred adhesions to reform a new vestibule. Then, a suitable grafting material [

4] is immediately applied to cover the opposing connective tissue surfaces thus, preventing further readhesion [

5,

6]. Split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) represented the standard separating material, as it provided abundant tissue to entirely resurface the opposing connective tissue walls [

7]. Despite the inherent disadvantages of STSG, such as, donor site morbidity, color and texture incompatibility, the main drawback was the difficulty in achieving a fixed nonmobile graft position during the healing period. This, in turn, led to either complete or partial graft loss and further readhesion or shrinkage [

7]. Later, the acellular dermal matrix (AlloDerm) was introduced as another grafting material that succeeded in sparing the disadvantages of donor site morbidity, color and texture incompatibility. Nevertheless, it was not able to overcome the fixation and stability problem that, subsequently led to complete or partial graft loss [

8]. Instead of managing the predicament by using grafts, researchers motivated their thinking toward using various types of splints to preserve the separated gap between the opposing connective tissue surfaces following their release until healing occurs [

5,

9].

Both the dynamic commissural splint and the Loma Linda stent represent the most frequently used methods. However, these splints suffered several drawbacks including patient intolerance, retention deficiency, technique complexity, and cost excessiveness. All these factors disabled these techniques and inhibited their further popularization [

10,

11].

In this study, we devised a simple, cheap, retentive, highly tolerable, and stable method—which we termed thermoplastic vestibuloplasty (TV)—to overcome the inherent disadvantages of the previously mentioned methods. The TV technique depends on aggressive removal of scarred tissues, creating the appropriate vestibular dimension followed by applying a specially prefabricated thermoplastic sheet and hence, we made use of the unprecedented mucosal capabilities to reepithelialize the opposing connective tissue surfaces. These sheets gain a firm stability from the teeth and its preformed shape extends to the full-created vestibular depth and rotates upward toward the lip side forming the desired vestibular space. It offers an excellent means of retention that is well tolerated by the patient. It also acts as a space maintainer that prevents readhesion until complete epithelial resurfacing occurs.

Patients and Methods

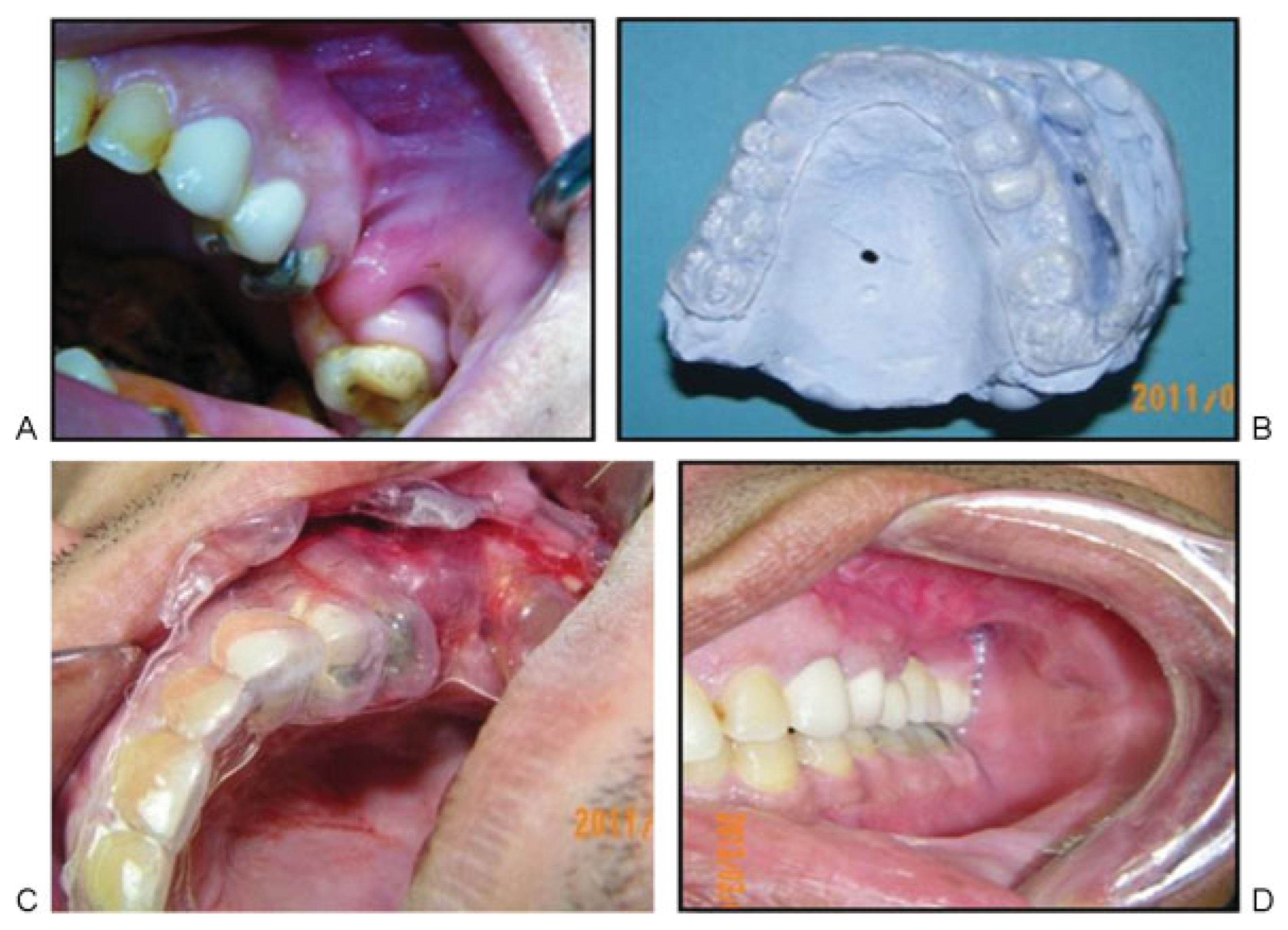

Ten patients suffering from vestibular loss and adhesion that varied from anterior lip (

Figure 1A,B) to posterior cheek area (

Figure 2A,B) were included with all data summarized in

Table 1. All patients received a thorough explanation of the procedure and then signed a written informed consent before enrollment.

An impression was performed using a modified special tray that allowed full accommodation of the adhesion area and extended toward the opposing lip or cheek. A virtual vestibule was performed on the model by creating a trough at the adhered area using a bur to match the desired dimension of the adjacent vestibular area. A special 1.5 mm semisoft thermoplastic sheet (Easy-vac, splint 60 = 1.5 mm; 3A MEDES (Gyeonggi-do, Korea)) was used and two bur holes were added to the model to ensure that the vacuum machine (Vacuum former, Easy-vac 3A MEDES) will force the heated sheet to delineate the full vestibular depth (

Figure 2B). The excess parts are trimmed from the sheet leaving the teeth undercuts up to just below the gingival margin to attain maximum retention.

Surgical Procedures

Under general anesthesia, the adherent area was sharply deepened to the preplanned vestibular dimension. Then, the prefabricated sheet was freely seated on place and any interfering tissues were carefully removed. The sheet periphery, which is inherently curved to 180 degrees, was sutured to the lip to prevent any stent movements

Figure 1C,D and

Figure 2C). Lip mobility was carefully checked and the patients were kept on soft diet and rigid cleaning protocol. Two weeks later, sutures were removed, stent was cleaned, and the patients were instructed to wear it continuously for another 2 weeks except during eating and cleaning.

Measurements and Assessment

Vestibular Length

The initial clinical vestibule length was measured from a specific spot at the alveolar margin or tooth to the deepest point in the vestibule then marked on the stent to ensure reproducibility

Table 2.

Lip or Cheek Mobility

Mobility was tested and compared with the adjacent normal sites according to a special scale where 0 refers to limited mobility, 1 refers to acceptable mobility with slight restriction, and 2 refers to free mobility without any restriction.

Patient Satisfaction

A written questionnaire of five items was provided to the patients to assess the following: speech, mastication, saliva drooling, restricted mobility, and overall patient satisfaction. All items were tested using 0 to 10 score tolerability for each item with a total score of 50.

All measurements were recorded and compared three times at baseline (preoperative), 2 weeks, and 3 months postoperatively. The means of the vestibular length, mobility, and visual analogue scale (VAS) score were compared using the paired t test (SPSS 10.0 for windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL; 2001), where p ≤ 0.05 is significant (S). All measurements were performed by the second author (A.A.).

Results

All the patients tolerated the procedures uneventfully. Minor complaints were reported in the first 2 weeks. Most of them resolved following suture removal including bad odor, difficulty in eating, and cleaning. The mean vestibule length significantly increased by 205% at 15 days postoperatively (

p < 0.001) (

Figure 1E), then it slightly decreased by (−14%) after 3 months with an overall increase of 163% (

p < 0.001) (

Table 2,

Figure 3). While the mean mobility score significantly increased from 0.3 preoperatively to 1.6 and 2 at 15 days and 3 months, respectively (100%) (

p < 0.001) (

Figure 1F and

Figure 2D). Moreover, the total VAS score significantly increased from 25.3 preoperatively to 38.1 (54%) and 50 (103%) at 15 days and 3 months, respectively (

p < 0.001).

Discussion

Reconstruction of the lip and cheek following their adhesion to the opposing gingiva continues to be a challenging situation in reconstructive maxillofacial surgery [

12]. The oral mucosa has a very powerful healing potential owing to the highly vascular connective tissue supply which leads to rapid adhesion between any bare connective tissue surfaces [

12]. This new TV technique uses a special prefabricated stent that curves to reach the proposed depth and rotates to resurface the opposing vestibular sides, until reepithelialization occurs. Thus, it prevents readhesion and maintains the achieved vestibular length. Those stents are simple, cheap, and obtain excellent retention from the teeth without any undesirable means of fixation. Several thermoplastic sheets were tested to configure the appropriate thickness and consistency required to offer enough stiffness to prevent collapse of the vestibule. At the same time, it can offer the desired resilience to contour the sheet to the vestibular fold depth. The 2 mm semisoft sheet was found to be the most appropriate to perform both functions. However, the fabrication method should be precisely followed to guarantee optimal results. Disadvantages included cleaning difficulties with consequent production of bad odor and slight speech impairment during the first 2 weeks which resolved spontaneously following intermittent application.

In this study, there was a statistically significant increase in the vestibule length at 15 days postoperatively. Although this achieved length slightly decreased after 3 months by −14%, it did not affect the overall significant increase of 163% (

p < 0.01). Our results are more stable and reliable when compared with Melo et al. [

2], who showed a 45% decrease in the gained vestibular length at 6 months despite the use of palatal grafts. In this study, the decrease in length may be attributed to continuous stretch of the muscles attached to the vestibule during the healing period. However, it can be better accommodated by increasing the initial planned length on the virtual cast. A significant increase in lip mobility was also achieved both at 15 days and 3 months postoperatively denoting successful increasing lip mobility. Patient satisfaction was assessed using a VAS composed of multiple scores, which recorded a significant increasing progress in all parameters indicating the tolerability and effectiveness of the TV technique.

Conclusions

TV represents a simple, reliable, cheap, and innovative technique for reconstruction of the deformed or lost vestibule following trauma, tumor, or thermal burns. Proper utilization of the rapid healing potential of the oral tissues with its high capability to reepithelialize by a tolerable retentive thermoplastic stents can simplify the treatment of a complex recurrent problem.