Frontal Sinus Obliteration with Iliac Crest Bone Grafts—Review of 8 Cases

Abstract

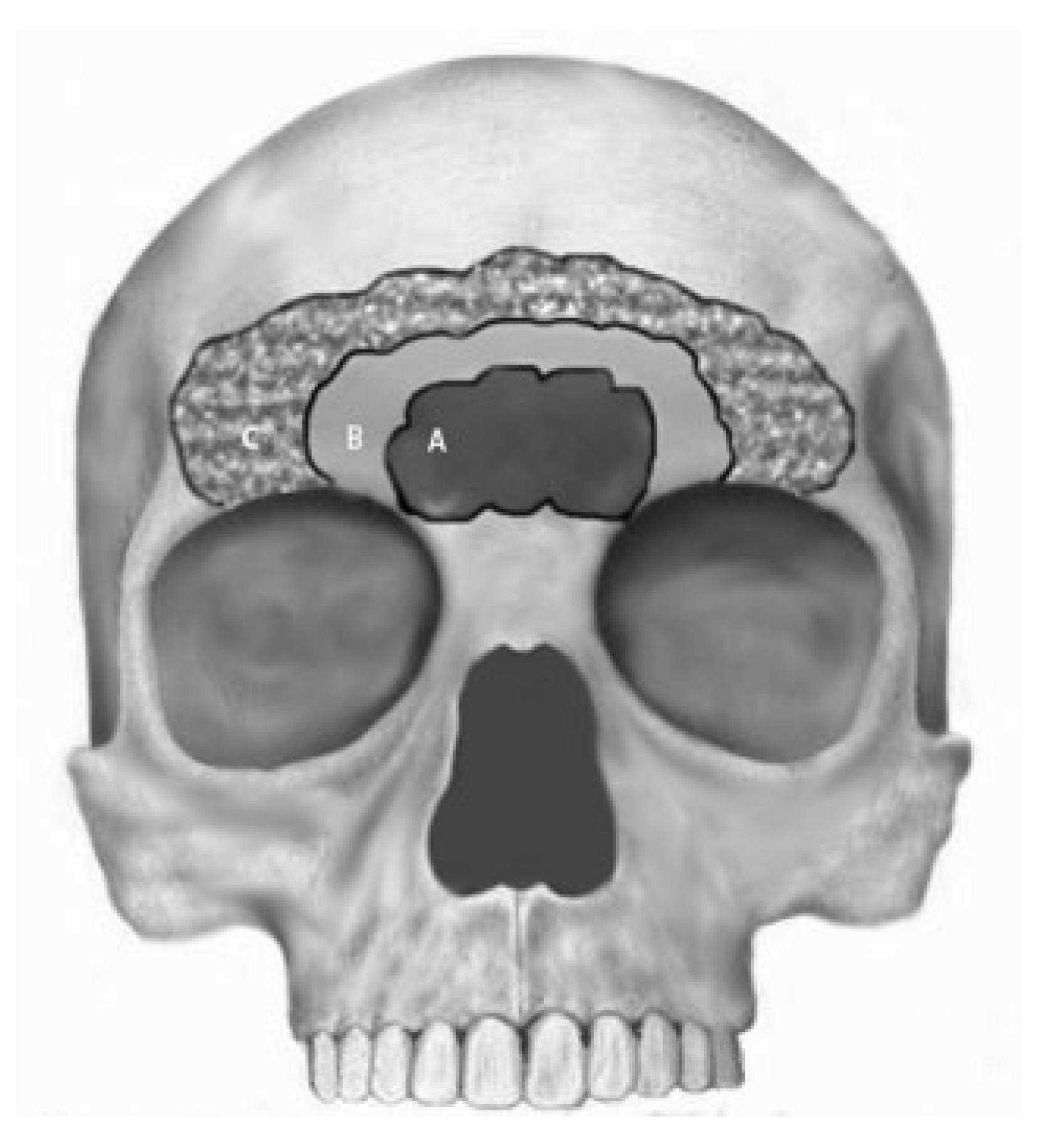

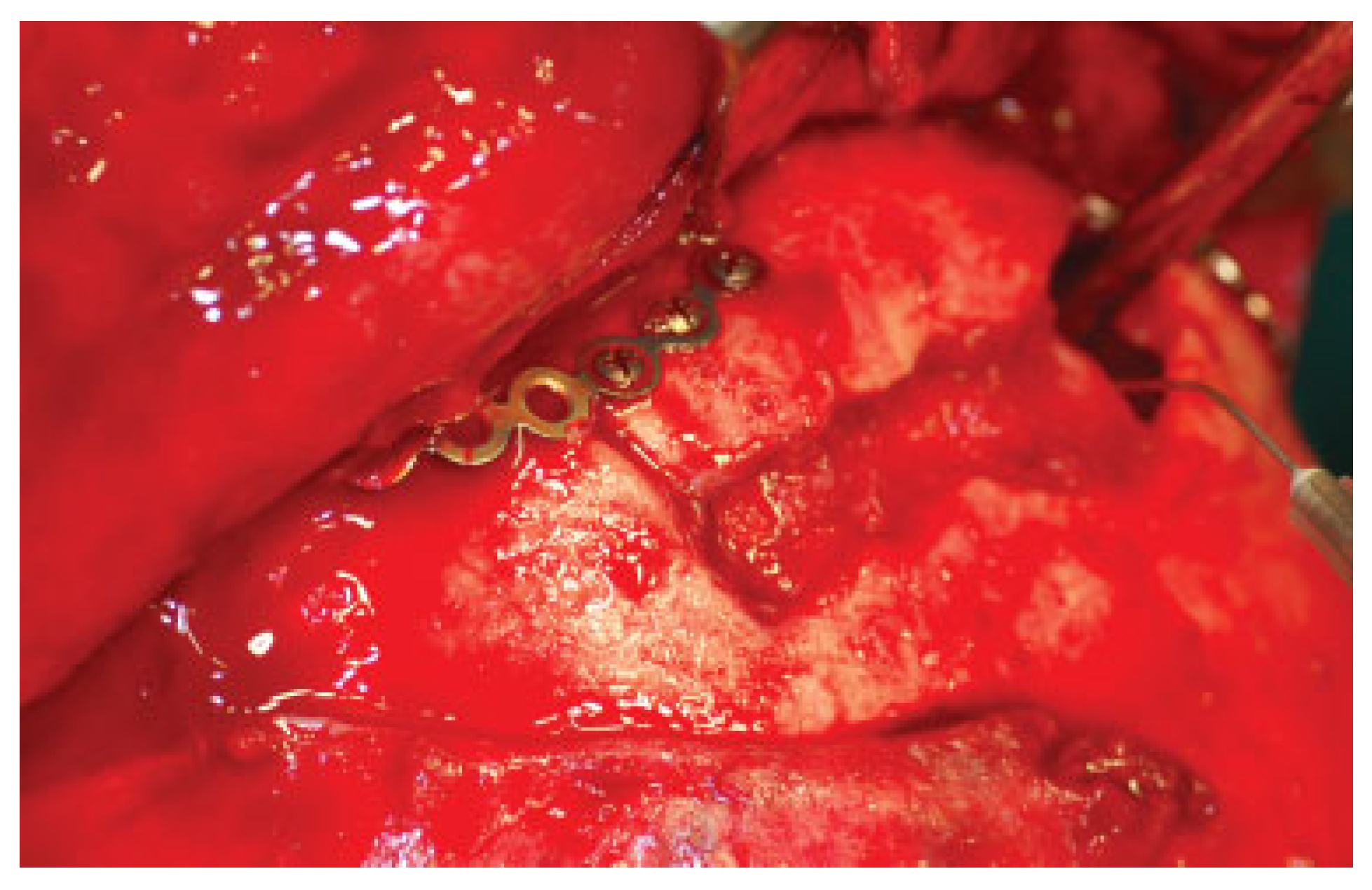

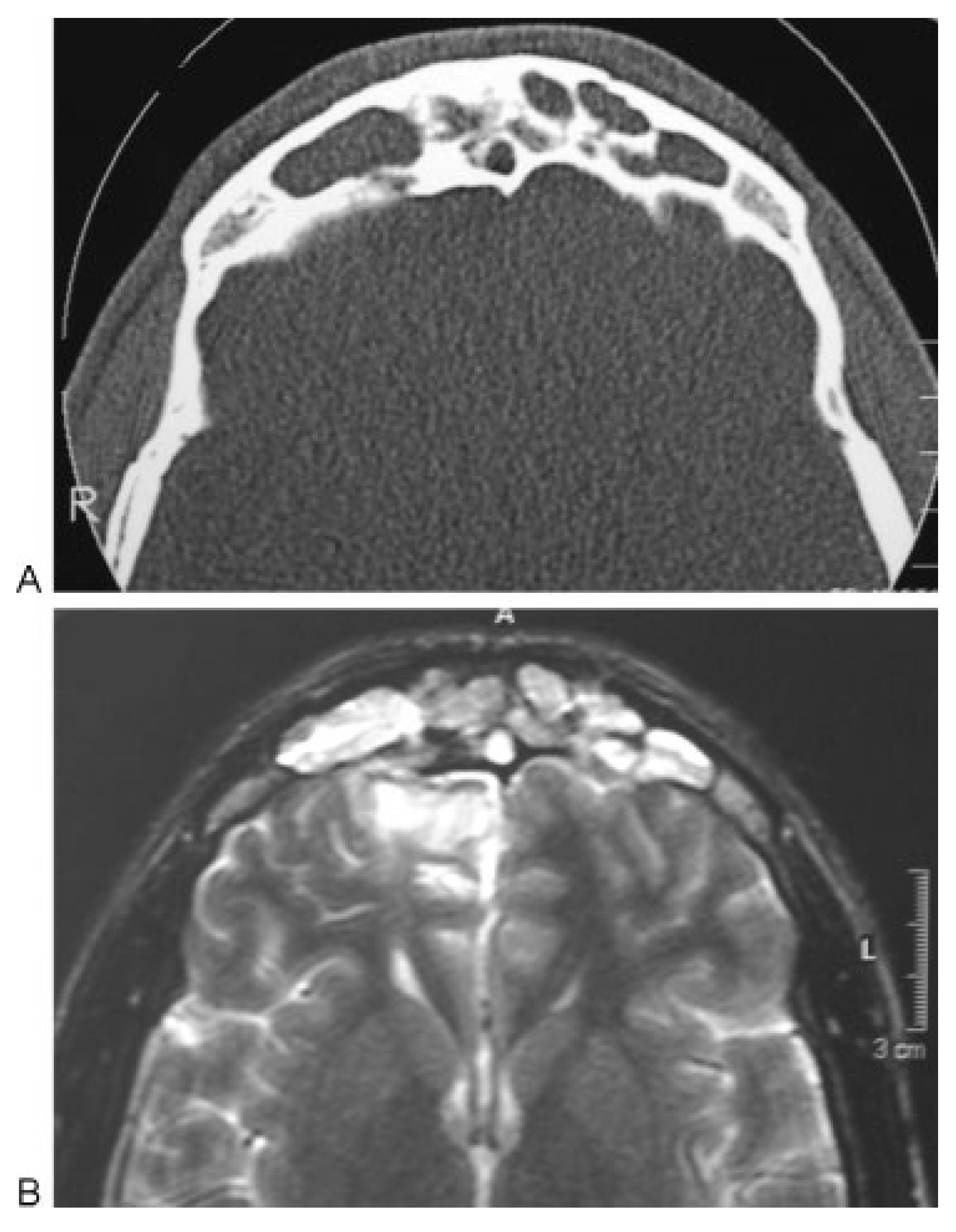

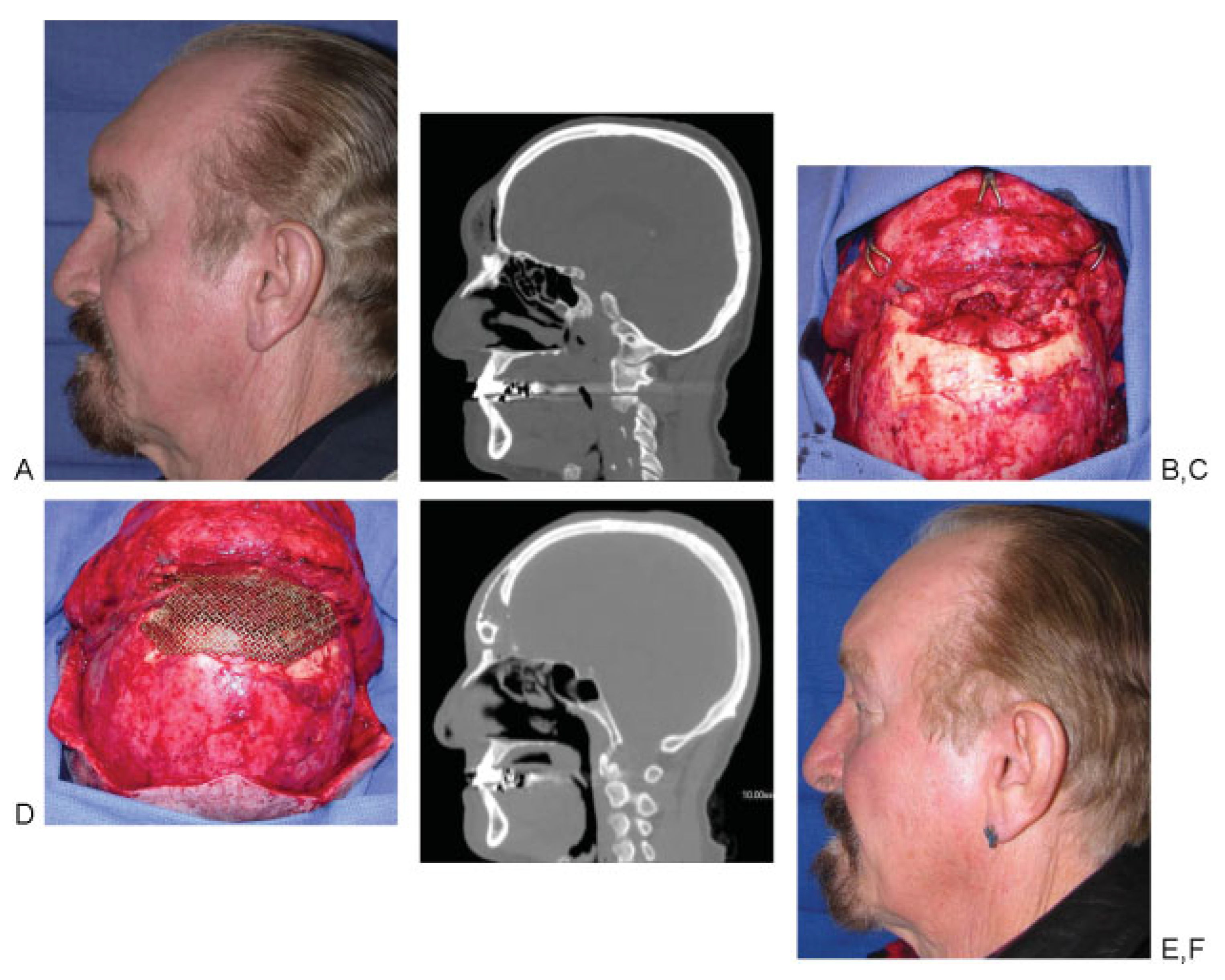

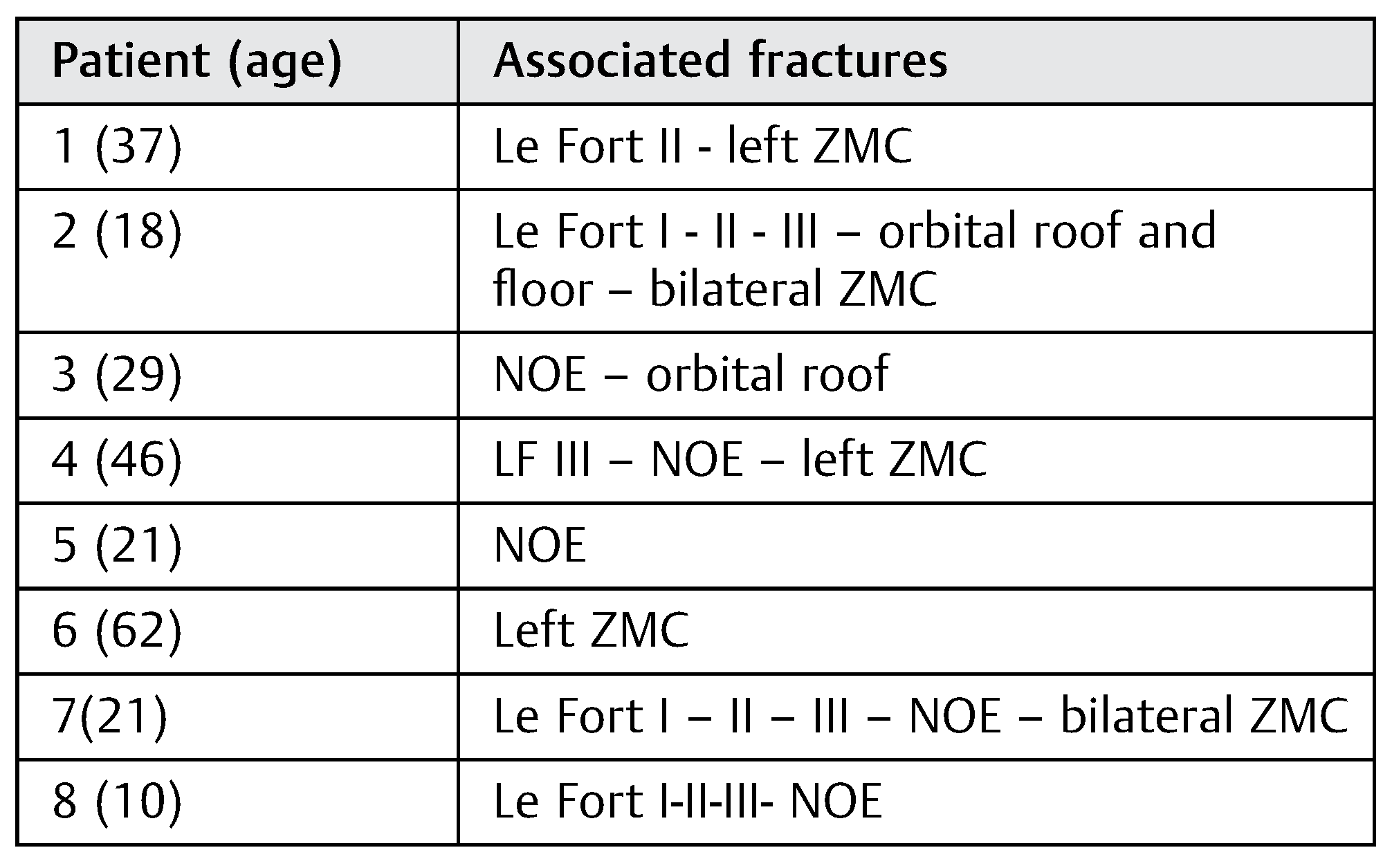

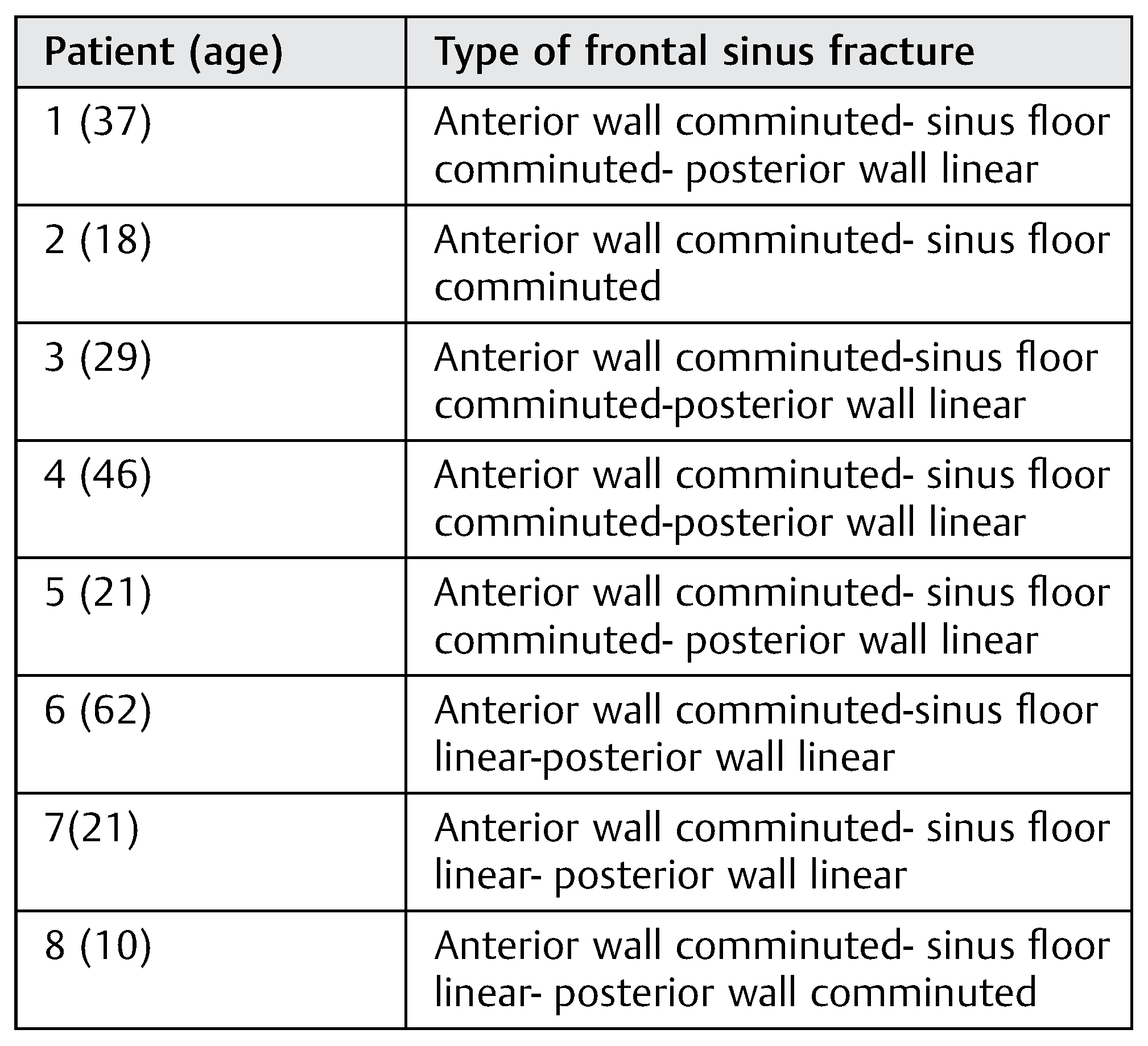

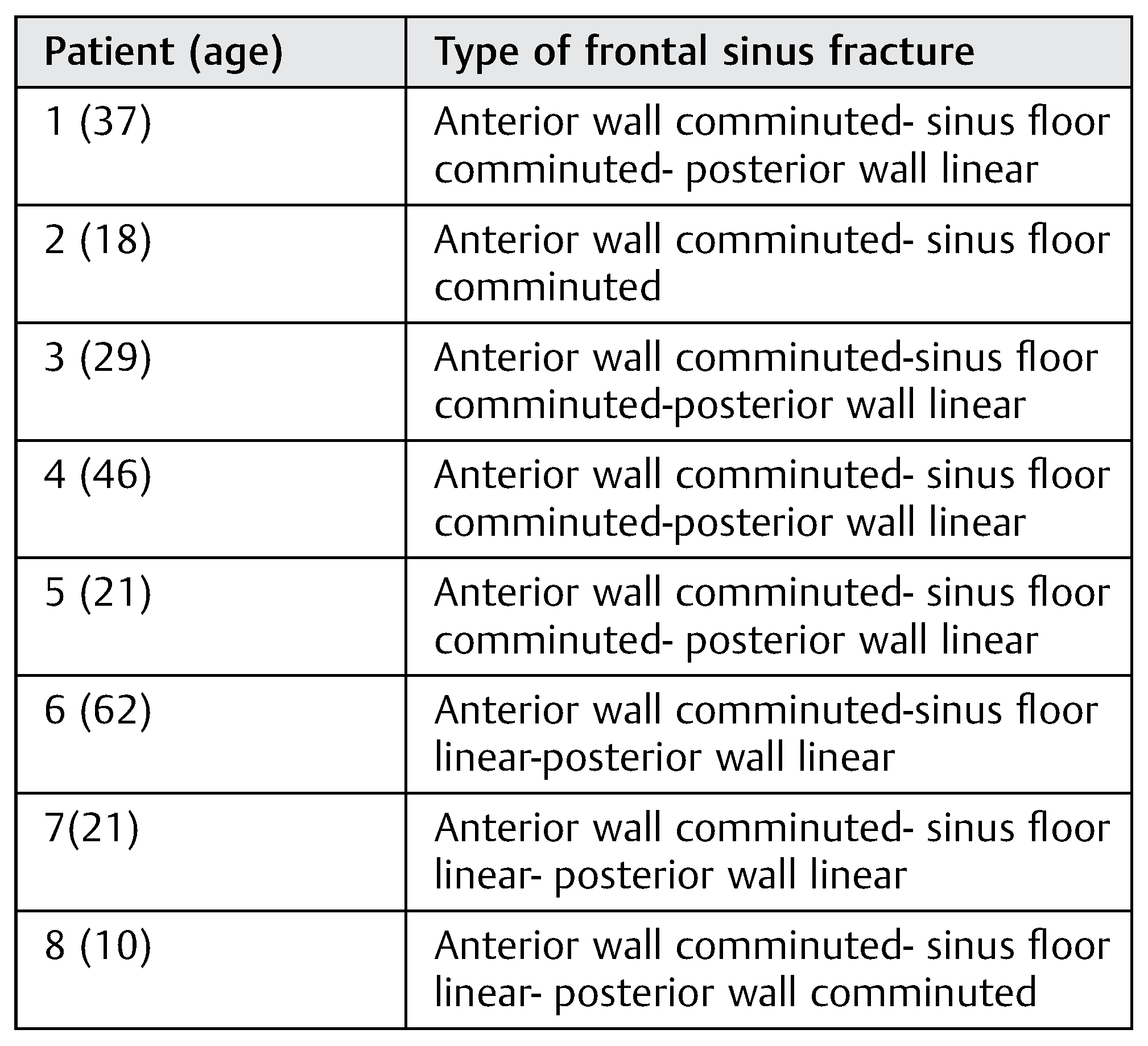

:Patients and Methods

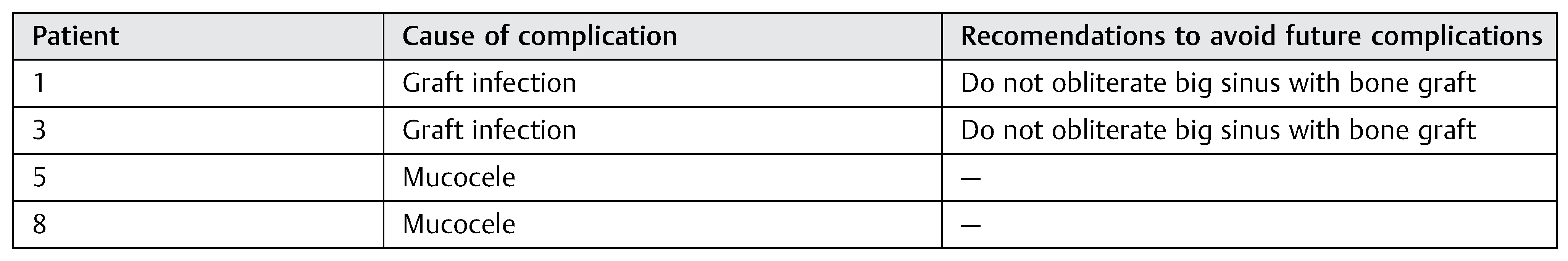

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Commentary

- Eduardo D. Rodriguez, MD, DDS

- Professor and Chair

- NYU Department of Plastic Surgery

- The Institute of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery

- New York University School of Medicine

- New York, New York

- Paul N. Manson, MD

- Professor of Surgery

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center

- University of Maryland Distinguished Service

- Professor Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

- Baltimore, Maryland

References

- Sataloff, R.T.; Sariego, J.; Myers, D.L.; Richter, H.J. Surgical management of the frontal sinus. Neurosurgery 1984, 15, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haug, R.H. Management of fractures of the frontal bone and sinus. In Principles of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; Peterson, L.J., Indresano, A.T., Marciani, R.D., et al., Eds.; JB Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, R.H.; Adams, J.M.; Conforti, P.J.; Likavec, M.J. Cranial fractures associated with facial fractures: a review of mechanism, type, and severity of injury. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994, 52, 729–733. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, M.; Kline, S.N. Management of frontal sinus fractures. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma 1995, 1, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ioannides, C.; Freihofer, H.P.M.; Bruaset, I. Trauma of the upper third of the face. Management and follow-up. J Maxillofac Surg 1984, 12, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godin, D.A.; Miller, R.H. Frontal sinus fractures. J La State Med Soc 1998, 150, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, K.B., Jr.; Poetker, D.M.; Rhee, J.S. Sinus preservation management for frontal sinus fractures in the endoscopic sinus surgery era: a systematic review. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr 2010, 3, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli, M.F.R.; Gabrielli, M.A.C.; Hochuli-Vieira, E.; Pereira-Fillho, V.A. Immediate reconstruction of frontal sinus fractures: review of 26 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004, 62, 582–586. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, R.B.; Dierks, E.J.; Brar, P.; Potter, J.K.; Potter, B.E. A protocol for the management of frontal sinus fractures emphasizing sinus preservation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007, 65, 825–839. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, S.A.; Johnson, P. Frontal sinus injuries: primary care and management of late complications. Plast Reconstr Surg 1988, 82, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, E.M.; Jacobs, J.B.; Holliday, R.A. Evaluation of the frontonasal duct in frontal sinus fractures. Head Neck 1989, 11, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Helmy, E.S.; Koh, M.L.; Bays, R.A. Management of frontal sinus fractures. Review of the literature and clinical update. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1990, 69, 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrich, R.J.; Hollier, L.H. Management of frontal sinus fractures. Changing concepts. Clin Plast Surg 1992, 19, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vrieus, J. Fractures of the frontal sinus: A rationale of treatment. Br J Plast Surg 1993, 46, 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannides, C.; Freihofer, H.P. Fractures of the frontal sinus: classification and its implications for surgical treatment. Am J Otolaryngol 1999, 20, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luce, E.A. Frontal sinus fractures: guidelines to management. Plast Reconstr Surg 1987, 80, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McRae, M.; Momeni, R.; Narayan, D. Frontal sinus fractures: a review of trends, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes at a level 1 trauma center in Connecticut. Conn Med 2008, 72, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Manolidis, S.; Hollier, L.H., Jr. Management of frontal sinus fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007, 120 (Suppl. 2), 32S–48S. [Google Scholar]

- Bluebond-Langner, R.; Jackowe, D.; Rodriguez, E.D. Simultaneous obliteration and treatment of infected frontal sinus fractures: novel use of the fibula flap. J Craniofac Surg 2007, 18, 680–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suonpää, J.; Sipilä, J.; Aitasalo, K.; Antila, J.; Wide, K. Operative treatment of frontal sinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1997, 529, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Jones, N.S. Frontal sinus obliteration. J Laryngol Otol 2004, 118, 637–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossman, D.G.; Archer, S.M.; Arosarena, O. Management of frontal sinus fractures: a review of 96 cases. Laryngoscope 2006, 116, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yavuzer, R.; Sari, A.; Kelly, C.P.; Tuncer, S.; Latifoglu, O.; Celevi, M.C.; Jackson, I.T. Management of frontal sinus fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005, 6, 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bergara, A.R. The obliteration of the sinus in the treatment of chronic frontal sinusitis. Trans Second Pan Am Congr Otorhinolaryng Bronchosophagol 1950, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Tato, J.M.; Sibbald, D.W.; Bergaglio, O.E. Surgical treatment of the frontal sinus by the external route. Laryngoscope 1954, 64, 504–521. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, R.H.; Likavec, M.J. Frontal sinus reconstruction. Atlas of Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin N Am 1994, 2, 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, P.J.; Lawson, W.; Som, P.; Biller, H.F. Radiographic evaluation and diagnosis of the failed frontal osteoplastic flap with fat obliteration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991, 104, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Fattahi, T.; Johnson, C.; Steinberg, B. Comparison of 2 preferred methods used for frontal sinus obliteration. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005, 63, 487–491. [Google Scholar]

- Taghizadeh, F.; Krömer, A.; Laedrach, K. Evaluation of hydroxyapatite cement for frontal sinus obliteration after mucocele resection. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2006, 8, 416–422. [Google Scholar]

- D’Addario, M.; Haug, R.H.; Talwar, R.M. Biomaterials for use in frontal sinus obliteration. J Long Term Eff Med Implants 2004, 14, 455–465. [Google Scholar]

- Petruzzelli, G.J.; Stankiewicz, J.A. Frontal sinus obliteration with hydroxyapatite cement. Laryngoscope 2002, 112, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrich, R.J.; Mickel, T.J. Frontal sinus obliteration: in search of the ideal autogenous material. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995, 95, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hochuli Vieira, E.; Real Gabrielli, M.F.; Garcia, I.R., Jr.; Cabrini Gabrielli, M.A. Frontal sinus obliteration with heterogeneous corticocancellous bone versus spontaneous osteoneogenesis in monkeys (Cebus apella), histologic analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003, 61, 214–221. [Google Scholar]

- Peltola, M.J.; Aitasalo, K.M.; Suonpää, J.T.; Yli-Urpo, A.; Laippala, P.J.; Forsback, A.P. Frontal sinus and skull bone defect obliteration with three synthetic bioactive materials. A comparative study. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2003, 66, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weber, R.; Draf, W.; Kahle, G.; Kind, M. Obliteration of the frontal sinus—state of the art and reflections on new materials. Rhinology 1999, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Elahi, M.M.; Vanduzer, S.; Spears, J.; Gibson, J.; Mitra, A. Frontal sinus obliteration with beta-tricalcium phosphate. J Craniofac Surg 2004, 15, 967–970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Acosta-Feria, M.; Infante-Cossío, P.; Hernández-Guisado, J.M.; et al. [Frontal sinus obliteration using tibial bone graft and platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis]. Neurocirugia (Astur) 2006, 17, 351–356, discussion 356. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça-Caridad, J.J.; Juiz-Lopez, P.; Rubio-Rodriguez, J.P. Frontal sinus obliteration and craniofacial reconstruction with platelet rich plasma in a patient with fibrous dysplasia. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006, 35, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.T.; Chen, C.T.; Mardini, S.; Tsay, P.K.; Chen, Y.R. Frontal sinus fractures: a treatment algorithm and assessment of outcomes based on 78 clinical cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006, 118, 457–468. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, R.; Draf, W.; Keerl, R.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging following fat obliteration of the frontal sinus. Neuroradiology 2002, 44, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kanowitz, S.J.; Batra, P.S.; Citardi, M.J. Comprehensive management of failed frontal sinus obliteration. Am J Rhinol 2008, 22, 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, E.D.; Stanwix, M.G.; Nam, A.J.; et al. Twenty-six-year experience treating frontal sinus fractures: a novel algorithm based on anatomical fracture pattern and failure of conventional techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008, 122, 1850–1866. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manson, P.N.; Stanwix, M.G.; Yaremchuk, M.J.; Nam, A.J.; Hui-Chou, H.; Rodriguez, E.D. Frontobasal fractures: anatomical classification and clinical significance. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009, 124, 2096–2106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, E.D.; Stanwix, M.G.; Nam, A.J.; St Hilaire, H.; Simmons, O.P.; Manson, P.N. Definitive treatment of persistent frontal sinus infections: elimination of dead space and sinonasal communication. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009, 123, 957–967. [Google Scholar]

- Bluebond-Langner, R.; Jackowe, D.; Rodriguez, E.D. Simultaneous obliteration and treatment of infected frontal sinus fractures: novel use of the fibula flap. J Craniofac Surg 2007, 18, 680–683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2014 by the author. The Author(s) 2014.

Share and Cite

Monnazzi, M.; Gabrielli, M.; Pereira-Filho, V.; Hochuli-Vieira, E.; de Oliveira, H.; Gabrielli, M. Frontal Sinus Obliteration with Iliac Crest Bone Grafts—Review of 8 Cases. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2014, 7, 263-270. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1382776

Monnazzi M, Gabrielli M, Pereira-Filho V, Hochuli-Vieira E, de Oliveira H, Gabrielli M. Frontal Sinus Obliteration with Iliac Crest Bone Grafts—Review of 8 Cases. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2014; 7(4):263-270. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1382776

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonnazzi, Marcelo, Marisa Gabrielli, Valfrido Pereira-Filho, Eduardo Hochuli-Vieira, Henrique de Oliveira, and Mario Gabrielli. 2014. "Frontal Sinus Obliteration with Iliac Crest Bone Grafts—Review of 8 Cases" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 7, no. 4: 263-270. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1382776

APA StyleMonnazzi, M., Gabrielli, M., Pereira-Filho, V., Hochuli-Vieira, E., de Oliveira, H., & Gabrielli, M. (2014). Frontal Sinus Obliteration with Iliac Crest Bone Grafts—Review of 8 Cases. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 7(4), 263-270. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1382776