Abstract

In many centers, computed tomography (CT) scan is preferred over plain film radio- graphs in the setting of acute nasal injury because CT scan is thought to be more sensitive in predicting nasal bone fracture. However, the usefulness of CT scans in predicting the need for surgery in acute nasal injury has not been well-studied. We conducted a retrospective review of 232 patients with known nasal bone fracture and found very similar rates of surgery in patients with a diagnosis of nasal fracture by CT scan as by nasal radiographs (41 and 37%, respectively). This suggests that experienced clinical examination remains the gold standard for determining the need for surgery in isolated nasal trauma, regardless of CT findings.

Computed tomography (CT) is the imaging modality of choice for evaluating facial trauma because of its ability to identify the exact anatomic location of fractures. CT reliably demon- strates fracture patterns and level of fracture severity [].CT has become essential for the evaluation and management of midfacial fractures, nasoethmoidal orbital fractures, and orbital fractures [,,,,]. In the case of complex facial fractures, the CT is critical in planning for reconstruction []. Fractures of the nasal bone account for roughly 40% of fractures of the facial skeleton []. However, unlike most other facial fractures, history and physical examination findings are often sufficient to diagnose a nasal fracture. The decisions regarding surgical approach (open vs. closed reduction), surgical timing and anesthesia are also generally based on clinical examination [,,]. Other radiographic techniques in-cluding plain film of the nasal bones are of limited clinical utility because they have a poor sensitivity and specificity profile. The films are frequently misread as positive and have not been shown to alter the course of treatment [,].

Many patients presenting with nasal trauma receive a facial CT for evaluation of their injury. While the clinical utility of CT in facial fractures has been clearly demonstrated, the role of CT scan for an isolated nasal fracture merits further evaluation. This study seeks to compare the rates of surgical intervention for patients with varying grades of nasal bone fracture identified by CTwith subjects with plain radiography and no imaging.

Methods

After approval by the research subjects of the review board, a retrospective chart review was conducted of all patients with the diagnosis of acute nasal fracture seen in the Otolaryngol- ogy Department our institution between January 1, 2008 and March 1, 2011. All male and female subjects above the age of 14 years with a chart and an International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 code for closed (802.0) or open (802.1) fracture within the specified date range were included in the study. All charts were reviewed using Allscripts (a medical record software) (Allscripts Healthcare Solutions, Inc., Chi- cago, IL) and images were viewed using Stentor (Stentor, Inc., San Francisco, CA).

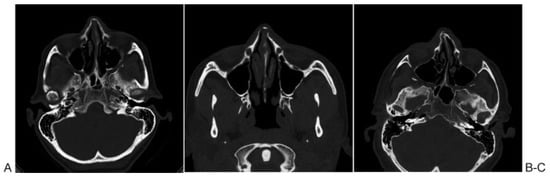

After initial review of the medical record, subjects were assigned to one of three groups based on the studies listed under the “Radiology” tab: maxillofacial/facial CT scan, X-ray of the nasal bones, no facial imaging. If there was a CT scan in the chart, the scan was immediately opened in Stentor without viewing the radiology impression, clinical descriptions of severity, or patient outcomes. Subjects with a CT scan were then further assigned to one of three subgroups, based on previous classification schema: (1) minimally displaced fracture of the nasal bone, (2) displaced fracture of the nasal bone without comminution or septal involvement, and (3) severe nasal bone fracture involving the nasal septum or comminution [,,,,]. (see Figure 1). Patients were excluded if they were found to have orbital or other maxillofacial fractures at any point during chart review.

Figure 1.

Modified nasal fracture classification schema based on Harrison and Strenc. (A) Group I: minimally displaced or nondisplaced fracture of the nasal bone with no septal involvement, (B) Group II: displaced nasal bone fracture without septal involvement, and (C) Group III: comminuted nasal bone fracture or nasal bone fracture involving the nasal septum.

After group assignment, subjects were given a random study number and their charts and billing data were further reviewed for age, gender, mechanism of injury, clinical de- scription of injury, and the mode of treatment of their injuries by CPT code (#21310–21337 for reduction of nasal bone fracture and #30400–30420 for septorhinoplasty). Subjects who received closed reduction of nasal fracture, open reduc- tion, or septorhinoplasty for their injury were recorded as having received surgical intervention.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Comparisons between groups were made using the Fisher exact test with two-tailed p values.

Results

Using the ICD-9 code of 802.0 or 802.1, 699 patient encoun- ters were identified totaling 411 patients. Of these 699 patients, 320 had a chart available for review; 34 patients were excluded because of other maxillofacial and orbital fractures; and 54 patients under the age of 14 were also excluded, leaving 232 study patients.

Of these 232 study patients, 56 had a CT scan, 78 patients had a plain-film radiograph, and 98 patients received no imaging. There was no difference in the rates of surgical intervention between patients who had CT scan versus X-ray (23/56 [41%] vs. 29/78 [37%], p = 0.7203). However, patients having no imaging (61/98 [62%]) were significantly more likely to have surgery than patients with CT (p = 0.0123) or X-ray (p = 0.0014). Patients who had a CT scan, there was no difference in rates of surgical treatment between patients with displaced versus severe fractures (7/12 [58%] vs. 13/26 [50%], p = 0.7342). Patients with nondisplaced/minimally displaced fractures (3/18 [17%]) were significantly less likely to require intervention than those with displaced (p = 0.045) or severe (p = 0.030) fractures (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Need for otolaryngology intervention by study group.

Discussion

While CT scan is generally considered the gold standard for sensitivity in diagnosing acute nasal fracture, it may not be useful in predicting the need for surgical treatment. On the basis of our findings, patients with a nasal bone fracture diagnosed by CT scan were no more likely to require surgery than those with a fracture diagnosed by plain radiograph. As previously mentioned, nasal radiography is generally consid- ered of little clinical utility: false-positive rates have been reported as high as 66%, [] and in a series of 100 consecutive patients presenting with nasal trauma, the nasal film did not alter management in a single case [].

CT scan by the very nature of its sensitivity may “over- diagnose” clinically less significant nasal injuries. Our results showed that nasal bone fractures diagnosed by CTor by plain- film radiograph were actually less likely to require interven- tion than those diagnosed without imaging (presumably by history and clinical examination). This supports our premise that CT can be overly sensitive and will identify many fractures that do not require surgery.

The severity system we employed in our study also had limited ability to distinguish those fractures that are clinically significant. While patients with minimally displaced fracture on CTwere less likely to require surgery than those with more severe fractures, there were a substantial number of patients with minimally displaced fractures on CT who still went to surgery. We also noted that there was no difference in rates of surgery between patients with comminution or septal in- volvement and those with simple displacement. These ob- servations suggest that the clinical evaluation was the primary element guiding surgical management, both in the setting of severe and less severe CT diagnosed fractures.

The cost of a CT scan clearly exceeds the cost of a careful physical examination. Thus, even though patients with less severe fractures by CT scan may be less likely to require surgical treatment, the cost of a CT scan should discourage its use to evaluate acute isolated nasal trauma, or to evaluate the severity of a known nasal bone fracture. However, maxil- lofacial CT scan remains a vital part of the work-up of a patient with suspected orbital or maxillofacial fractures in the setting of a secondary trauma survey.

Another important aspect of our study was the finding that patients with no facial imaging were much more likely to have surgery than those who had CT or plain radiographs. It is thought that a clinically evident or bothersome nasal defor- mity was more likely to cause these patients to seek follow- up. Similarly, there may have been a substantial number of patients with CT scan or nasal radiographs who sought follow-up simply because diagnostic studies had reported a fracture. It is also possible that patients with more clinically equivocal nasal deformities were sent for imaging to aid in the diagnosis.

Even though CT is described as the gold standard of sensitivity for nasal bone fracture, some authors have suggested other imaging modalities as superior. High-resolution ultrasonogra- phy was found to be more sensitive than both CT and radiogra- phy in a study of 140 patients and in another study of 87 patients [,]. Other studies have suggested that the diagnostic accuracy of CT scan for nasal trauma can be enhanced by the addition of sagittal multiplanar reconstruction CT [].

This study has some inherent limitations due to its retro- spective approach. Future studies could prospectively com- pare rates of operative and nonoperative treatment in patients with CT and other imaging modalities in the setting of isolated acute nasal trauma.

Conclusions

Our results show that in patients with isolated nasal trauma, a nasal bone fracture found on CT scan does not reliably predict the need for surgical treatment. The majority (59%) of nasal bone fractures diagnosed by CT did not undergo surgery. This is similar to what has been previously reported for nasal bone radiographs. Even patients with fracture comminution or septal involvement on CT had surgery only 50% of the time. These results suggest that regardless of CT findings, only those patients with clinically evident nasal deformity on physical examination will undergo surgery.

References

- Manson, P.N.; Markowitz, B.; Mirvis, S.; Dunham, M.; Yaremchuk, M. Toward CT-based facial fracture treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg 1990, 85, 202–212, discussion 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.K.; LeMay, D.R. Imaging of facial trauma. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2002, 12, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escott, E.J.; Branstetter, B.F. Incidence and characterization of unifocal mandible fractures on CT. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008, 29, 890–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmler, D.; Denny, A.; Gosain, A.; Subichin, S. Role of three-dimen- sional computed tomography in the assessment of nasoorbitoeth- moidal fractures. Ann Plast Surg 2000, 44, 553–562, discussion 562–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargent, L.A. Nasoethmoid orbital fractures: diagnosis and treat- ment. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007, 120 7, Suppl. 2, 16S–31S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Barrera, J.E.; Jung, T.Y.; Most, S.P. Measurements of orbital volume change using computed tomography in isolated orbital blowout fractures. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2009, 11, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraioli, R.E.; Branstetter, B.F.I.V.; Deleyiannis, F.W. Facial fractures: beyond Le Fort. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2008, 41, 51–76, vi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucik, C.J.; Clenney, T.; Phelan, J. Management of acute nasal fractures. Am Fam Physician 2004, 70, 1315–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Mondin, V.; Rinaldo, A.; Ferlito, A. Management of nasal bone fractures. Am J Otolaryngol 2005, 26, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, G.J. Management of nasal fractures. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991, 24, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Ghasemi-Rad, M. Nasal bone fracture—ultrasonog- raphy or computed tomography? Med Ultrasound 2011, 13, 292–295. [Google Scholar]

- Nigam, A.; Goni, A.; Benjamin, A.; Dasgupta, A.R. The value of radio- graphs in the management of the fractured nose. Arch Emerg Med 1993, 10, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stranc, M.F.; Robertson, G.A. A classification of injuries of the nasal skeleton. Ann Plast Surg 1979, 2, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, D.H. Nasal injuries: their pathogenesis and treatment. Br J Plast Surg 1979, 32, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, R.A. Nasal trauma. Pathomechanics and surgical manage- ment of acute injuries. Clin Plast Surg 1992, 19, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.A.; Maran, A.G.; Busuttil, A.; Vaughan, G. A pathological classification of nasal fractures. Injury 1986, 17, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; You, S.H.; Kim, S.G.; Lee, S.I. Analysis of nasal bone fractures; a six-year study of 503 patients. J Craniofac Surg 2006, 17, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lacey, G.J.; Wignall, B.K.; Hussain, S.; Reidy, J.R. The radiology of nasal injuries: problems of interpretation and clinical relevance. Br J Radiol 1977, 50, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, M.; O’Driscoll, K.; Masterson, J. The utility of nasal bone radiographs in nasal trauma. Clin Radiol 1994, 49, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Cha, J.G.; Hong, H.S.; et al. Comparison of high-resolution ultrasonography and computed tomography in the diagnosis of nasal fractures. J Ultrasound Med 2009, 28, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Seo, H.S.; Kim, A.Y.; et al. The diagnostic value of the sagittal multiplanar reconstruction CT images for nasal bone fractures. Clin Radiol 2010, 65, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2013 by the authors. The Author(s) 2013.