Superolateral Dislocation of Bilateral Intact Condyles—An Unusual Presentation: Report of a Case and Review of Literature

Abstract

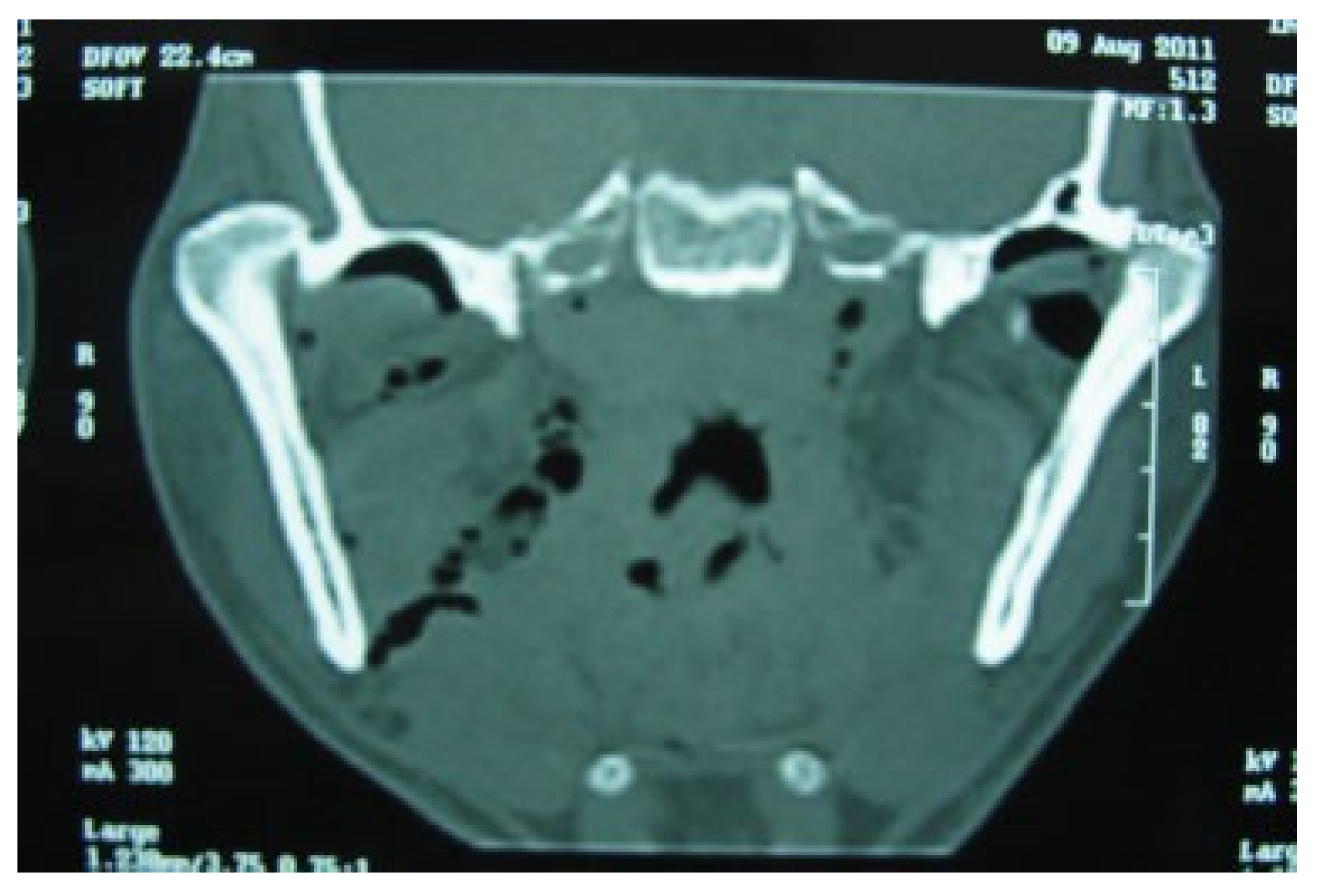

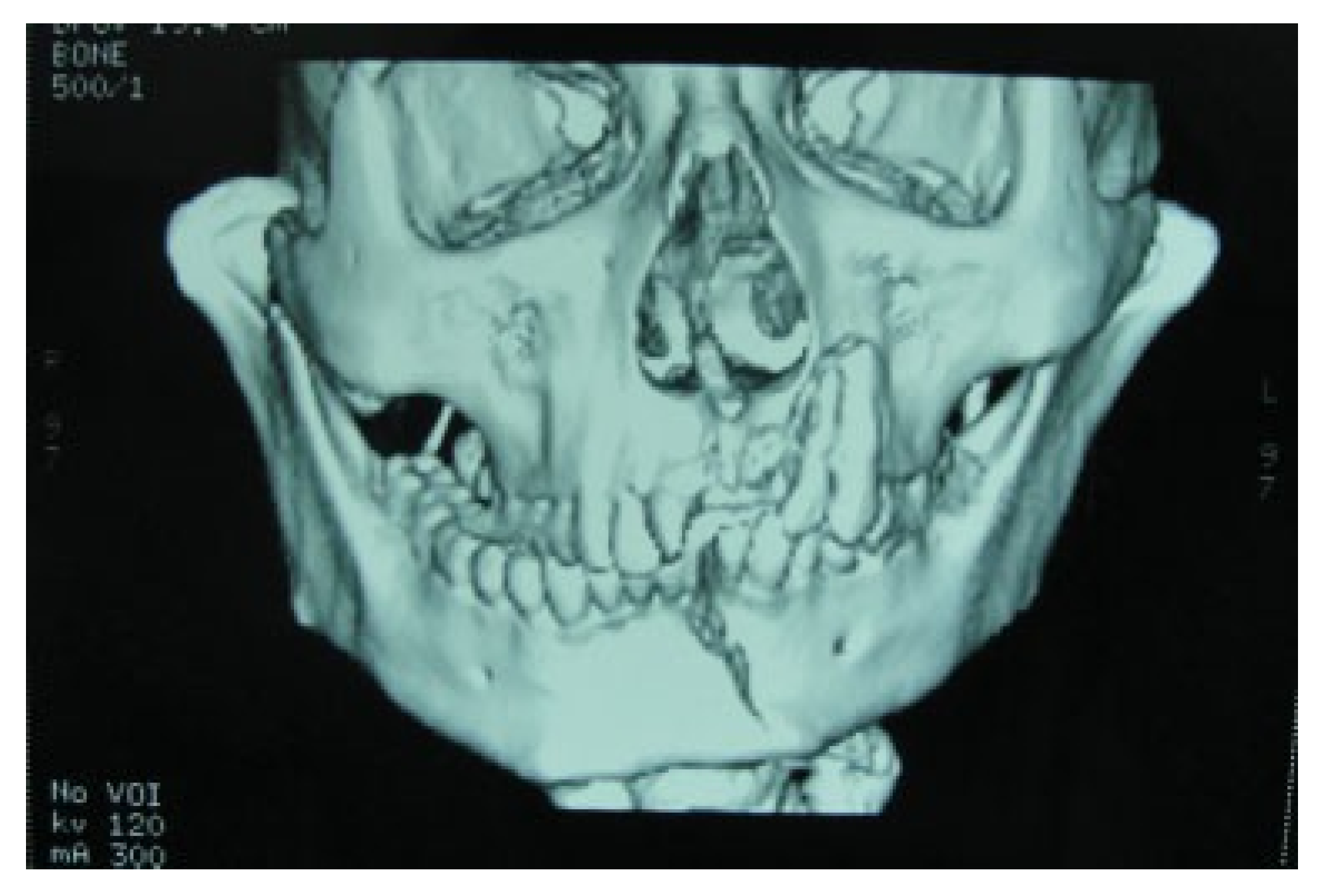

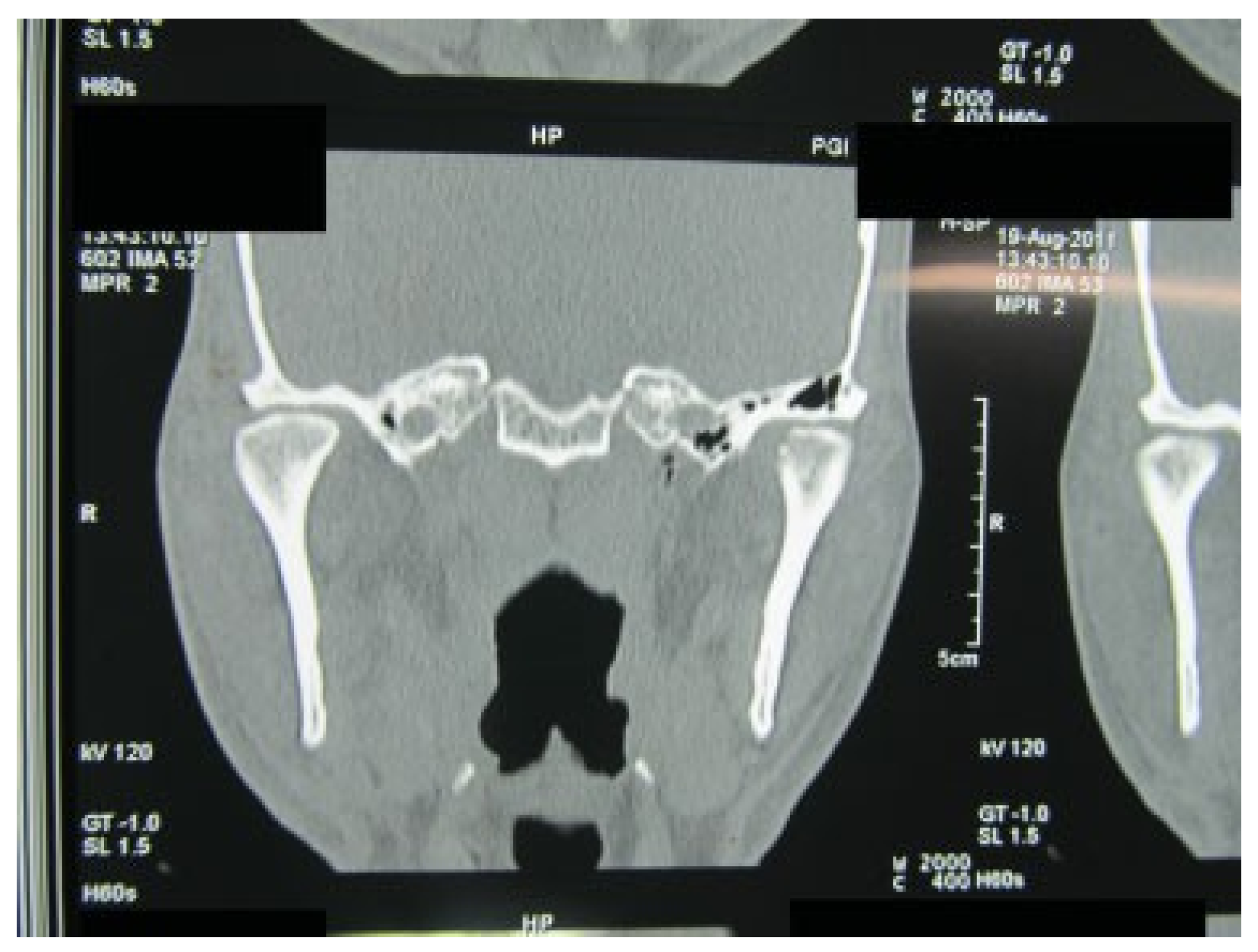

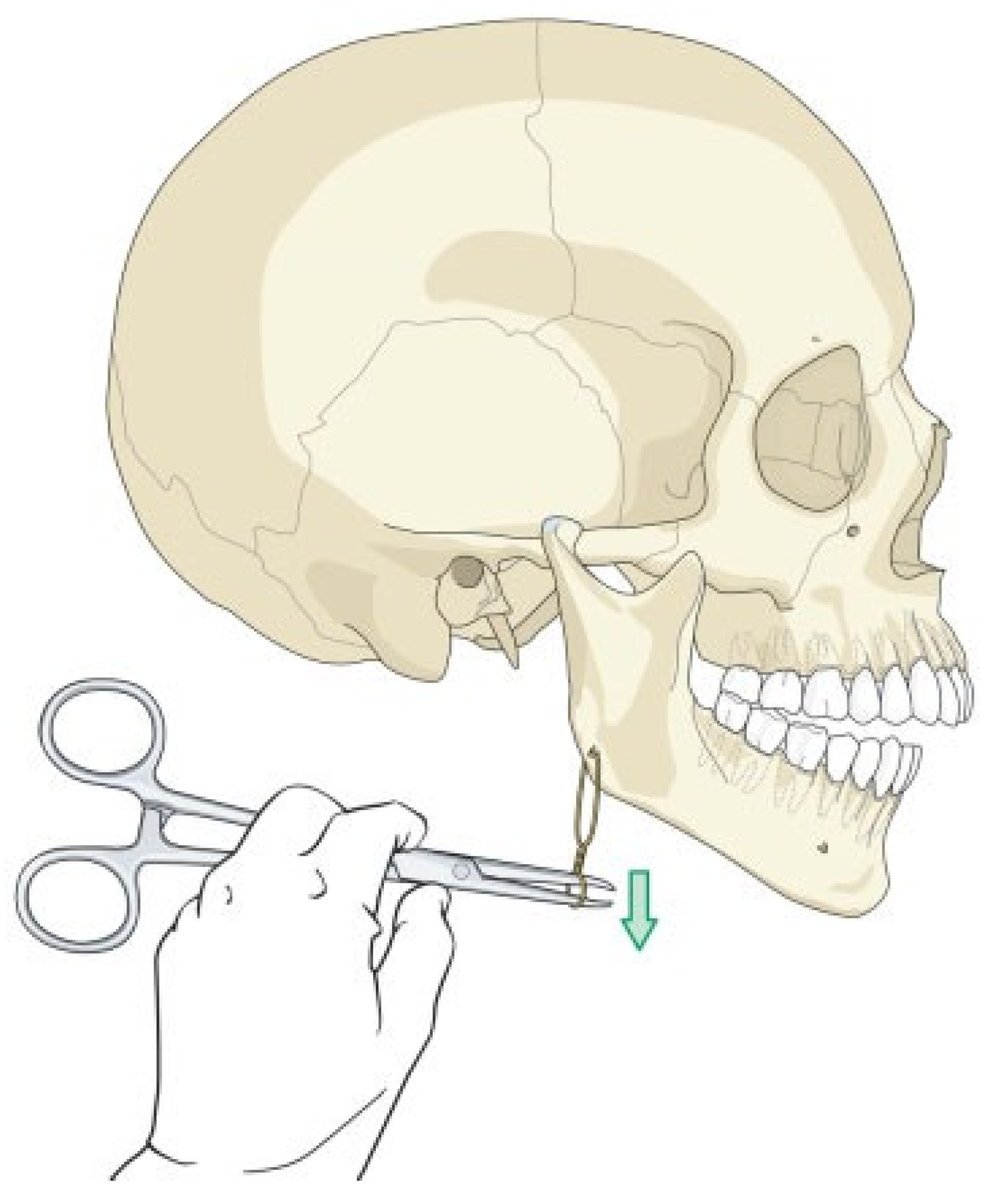

:1. Case Report

2. Discussion

References

- Sang, L.K.; Mulupi, E.; Akama, M.K.; et al. Temporomandibular joint dislocation in Nairobi. East Afr. Med. J. 2010, 87, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- deB Norman, J.E.; Bramley, P. Text Book and Colour Atlas of the Temporomandibular Joint; Wolfe Med publ Ltd.: London, UK, 1990; pp. 136–150. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, P. Dislocation of the mandibular condyle into the temporal fossa. J Maxillofac Surg 1982, 10, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, F.J.; Young, A.H. Lateral displacement of the intact mandibular condyle. A report of five cases. Br J Oral Surg 1969, 7, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, K.; Suzuki, H.; Matsuzaki, S. A type II lateral dislocation of bilateral intact mandibular condyles with a proposed new classification. Plast Reconstr Surg 1994, 93, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapila, B.K.; Lata, J. Superolateral dislocation of an intact mandibular condyle into the temporal fossa: A case report. J Trauma 1996, 41, 351–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshii, T.; Hamamoto, Y.; Muraoka, S.; et al. Traumatic dislocation of the mandibular condyle into the temporal fossa in a child. J Trauma 2000, 49, 764–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ord, R.A.; EI-Attar, A. Long-standing mandibular dislocations: Report of a case, review of the literature. Br Dent J 1986, 160, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kallal, R.H.; Gans, B.J.; Lagrotteria, L.B. Cranial dislocation of mandibular condyle. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1977, 43, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusati, R.; Paini, P. Facial nerve injury secondary to lateral displacement of the mandibular ramus. Plast Reconstr Surg 1978, 62, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rattan, V. Superolateral dislocation of the mandibular condyle: Report of 2 cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002, 60, 1366–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, J.R. Prolonged dislocation of the mandible. J Oral Surg 1965, 23, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bu, S.S.; Jin, S.L.; Yin, L. Superolateral dislocation of the intact mandibular condyle into the temporal fossa: Review of the literature and report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007, 103, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVita, C.L.; Friedman, J.M.; Meyer, S.; Breiman, A. An unusual case of condylar dislocation. Ann Emerg Med 1988, 17, 534–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J.W.; Stewart, I.A.; Whitley, B.D. Lateral displacement of the intact mandibular condyle. Review of literature and report of case with associated facial nerve palsy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1989, 17, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, E.W.H. Supero-lateral dislocation of sagittally split bifid man- dibular condyle. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1989, 27, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoard, M.A.; Tadje, J.P.; Gampper, T.J.; Edlich, R.F. Traumatic chronic TMJ dislocation: Report of an unusual case and discussion of management. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma 1998, 4, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.H.; Chen, C.T.; Tsai, H.H.; Lai, J.P. Lateral dislocation of bilateral intact mandibular condyles with symphysis fracture: A case report. J Trauma 2007, 62, 1518–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, H.; Edwards, R.S. Superolateral dislocation of the condyle: Report of a rare case. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010, 39, 508–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhakar, V.; Singla, S. Bilateral anterosuperior dislocation of intact mandibular condyles in the temporal fossa. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011, 40, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Authors | Type | Uni- or Bilateral | Reduction Time (d) | Reduction | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Allen and Young [4] | I | U | 8 | Partial (C) | Fibro-osseous ankylosis |

| II | U | 15 | Nil (C) | Gross malocclusion | ||

| I | B | 1 | Complete (C) | 25% reduction | ||

| I | U | 1 | Complete (C) | Full range of jaw movements | ||

| II | U | 1 | Complete (C) | Not available | ||

| 1978 | Brusati and Paini [10] | II | U | 1 | Complete (C) | With facial palsy, not detailed |

| II | U | 12 | Complete (O) | With facial palsy and full range of jaw function | ||

| 1982 | Worthington [3] | Unusual | U | 14 | Partial (O) | Fibro-osseous ankylosis |

| 1988 | DeVita et al. [14] | II | B | NA | Complete (O) | Not available |

| 1989 | Ferguson et al. [15] | II | U | 1 | Complete (O) | Condylectomy, arthroplasty by costal cartilage; mouth opening 30 mm |

| 1989 | To [16] | II | U | 14 | Complete (O) | Bifid condyle, reduced mouth opening |

| 1994 | Satoh et al. [5] | II | B | 13 | Partial (O) | Condylectomy, 30-mm mouth opening |

| 1996 | Kapila and Lata [6] | II | U | 7 | Complete (O) | 30-mm mouth opening |

| 1998 | Hoard et al. [17] | II | B | NA | Complete (C) | Not available |

| 2000 | Yoshii et al. [7] | II | B | 16 | Complete (C) | 20-mm mouth opening |

| 2002 | Rattan [11] | II | U | 14 | Complete (O) | 30-mm mouth opening |

| II | B | NA | Not reduced | Interpositional gap arthroplasty | ||

| 2007 | Hsieh et al. [18] | II | B | 1 | Complete (C) | 41-mm mouth opening |

| 2007 | Bu et al. [13] | II | U | 5 | Complete (C) | 37-mouth opening |

| 2010 | Papadopoulos and Edwards [19] | II | U | 1 | Complete (C) | 32-mm mouth opening with 5 mm lateral excursions |

| 2011 | Prabhakar and Singla [20] | III | B | 45 | Complete (O) | 33-mm mouth opening with adequate mandibular function and satisfactory occlusion |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2008 by the author. The Author(s) 2008.

Share and Cite

Singh, V.; Gupta, P.; Khatana, S.; Bhagol, A. Superolateral Dislocation of Bilateral Intact Condyles—An Unusual Presentation: Report of a Case and Review of Literature. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2013, 6, 205-210. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1343780

Singh V, Gupta P, Khatana S, Bhagol A. Superolateral Dislocation of Bilateral Intact Condyles—An Unusual Presentation: Report of a Case and Review of Literature. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2013; 6(3):205-210. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1343780

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Virendra, Pranav Gupta, Shruti Khatana, and Amrish Bhagol. 2013. "Superolateral Dislocation of Bilateral Intact Condyles—An Unusual Presentation: Report of a Case and Review of Literature" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 6, no. 3: 205-210. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1343780

APA StyleSingh, V., Gupta, P., Khatana, S., & Bhagol, A. (2013). Superolateral Dislocation of Bilateral Intact Condyles—An Unusual Presentation: Report of a Case and Review of Literature. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 6(3), 205-210. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1343780