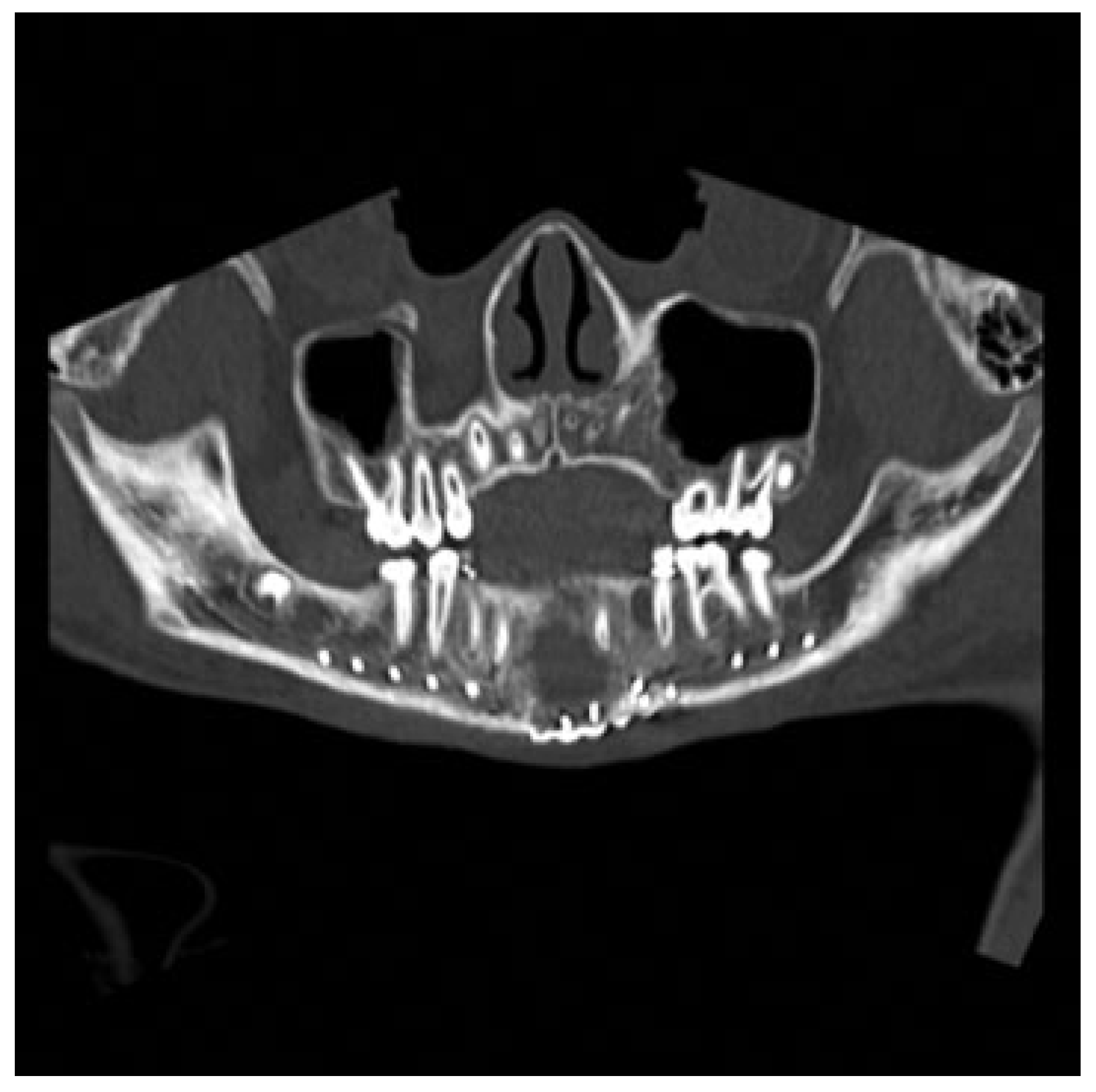

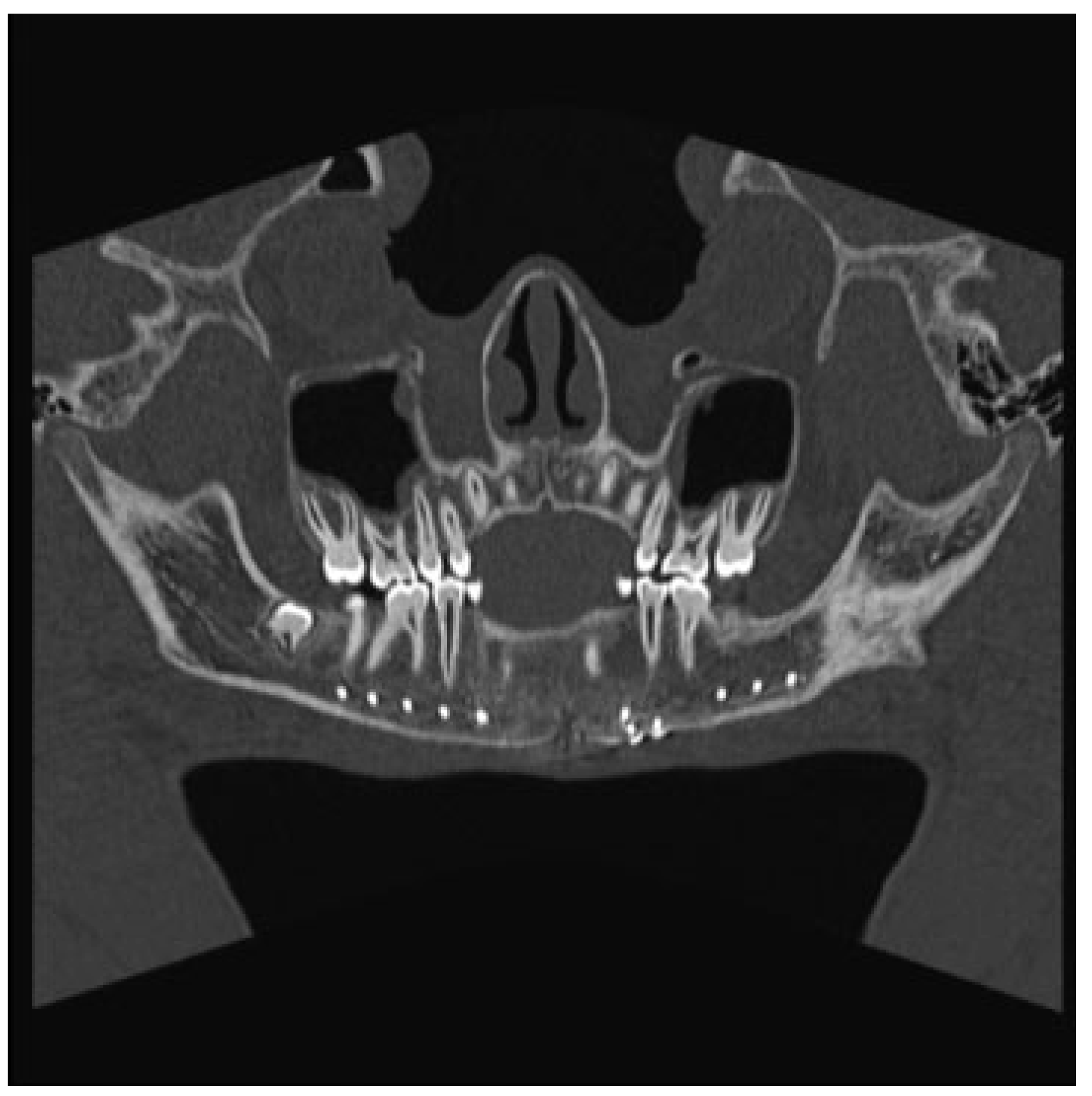

Pathologic Fracture of the Mandible Secondary to Traumatic Bone Cyst

Abstract

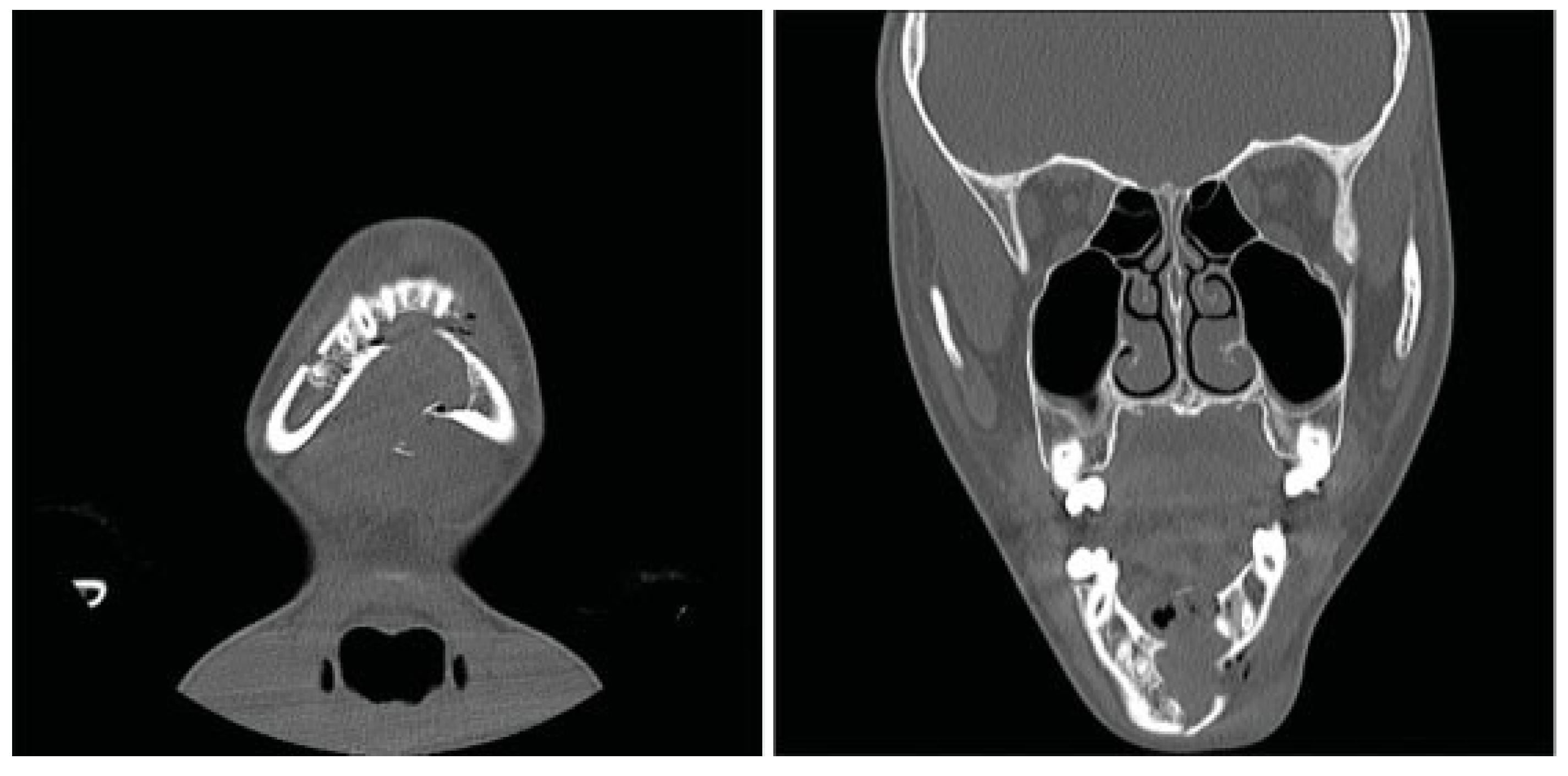

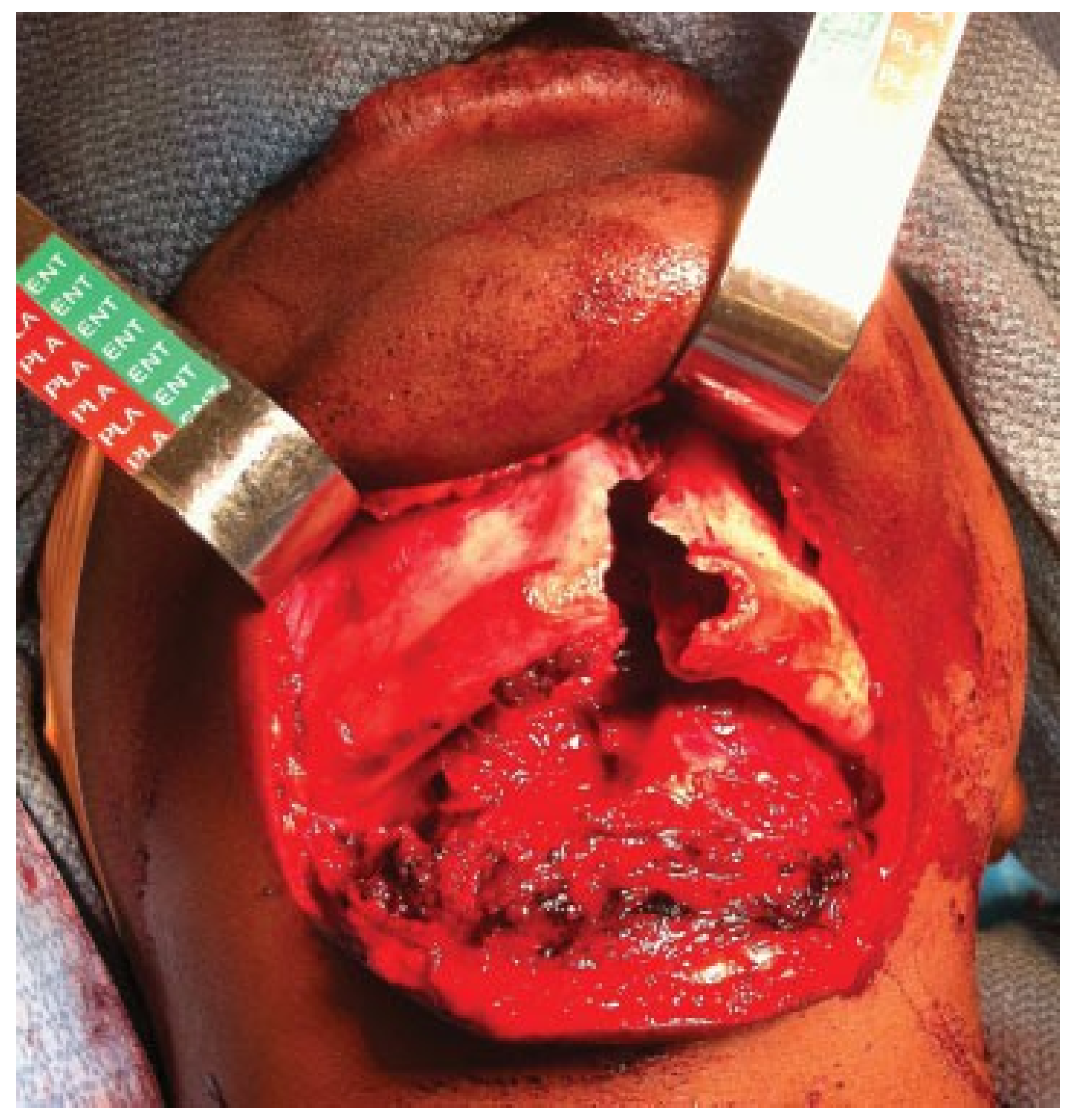

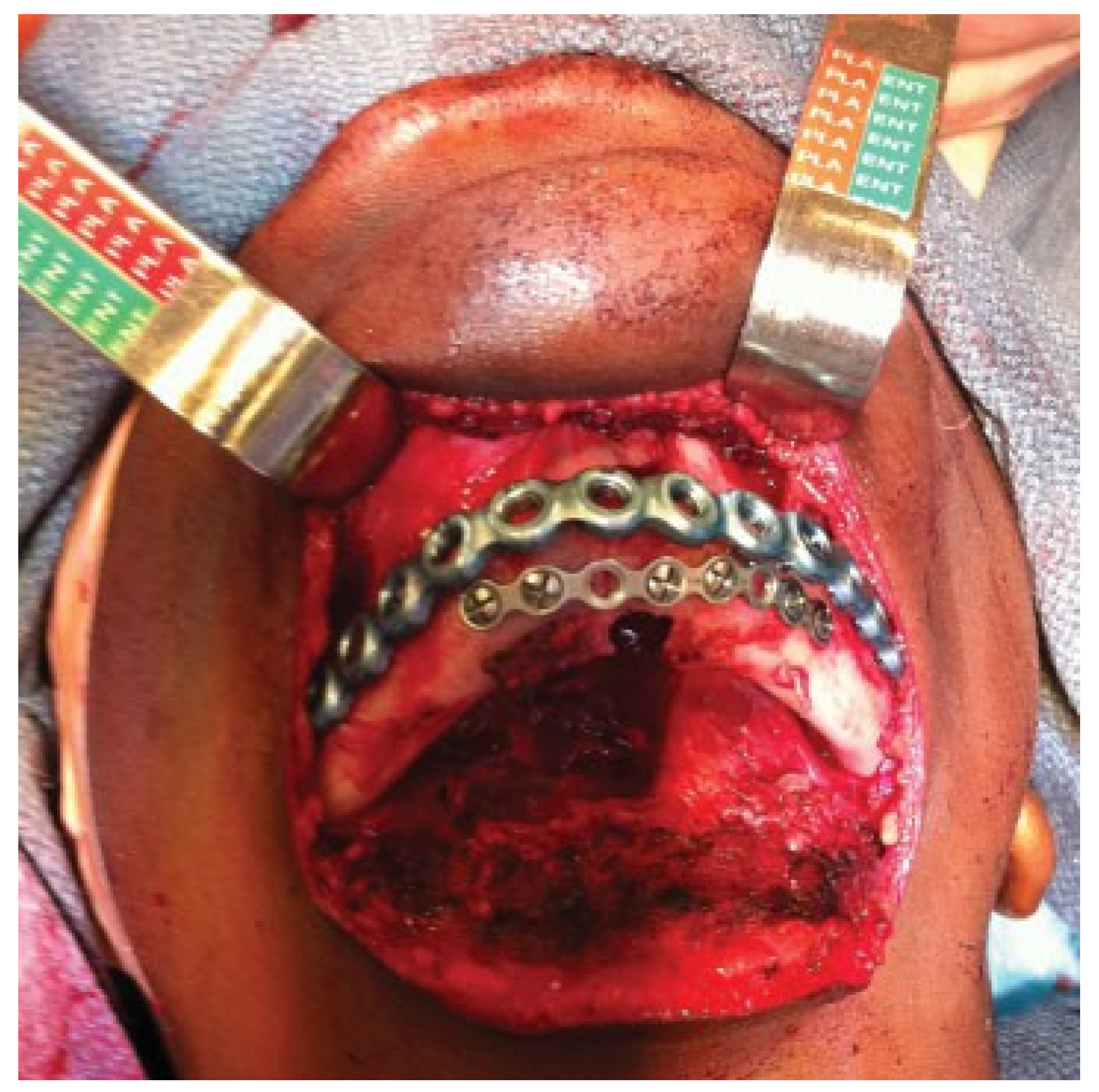

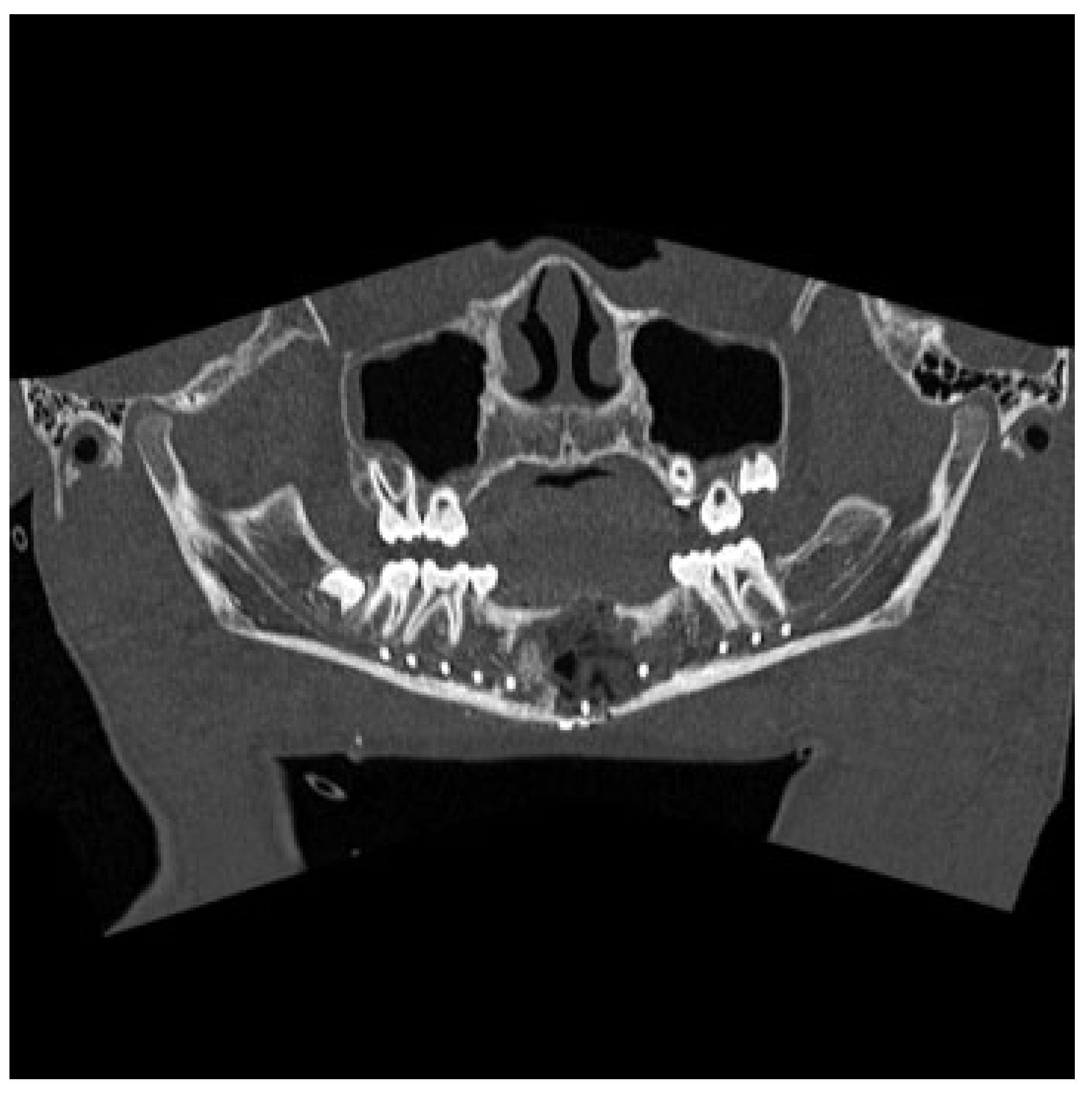

:1. Case Report

2. Discussion

References

- Lucas, C.; Blum, T. Do all cysts of the jaws originate from the dental system. J Am Dent Assoc 1929, 16, 659–661. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C.L. Hemorrhagic bone cyst and pathologic fracture of mandible: Report of case. J Oral Surg 1969, 27, 345–346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baird, W.O.; Askew, P.A. Traumatic mandibular bone cyst involved in line of fracture. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1958, 11, 1351–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, C.E.; Troulis, M.J.; Kaban, L.B. Pediatric facial fractures: Recent advances in prevention, diagnosis and management. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005, 34, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazer, M.; Joshua, B.Z.; Woldenberg, Y.; Bodner, L. Mandibular frac- tures in children: Analysis of 61 cases and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2011, 75, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xanthinaki, A.A.; Choupis, K.I.; Tosios, K.; Pagkalos, V.A.; Papanikolaou, S.I. Traumatic bone cyst of the mandible of possible iatrogenic origin: A case report and brief review of the literature. Head Face Med 2006, 2, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald-Jankowski, D.S. Traumatic bone cysts in the jaws of a Hong Kong Chinese population. Clin Radiol 1995, 50, 787–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, G.L. “Haemorrhagic cysts” of the mandible. I. Br J Oral Surg 1965, 3, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, L.S.; Sapone, J.; Sproat, R.C. Traumatic bone cysts of jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1974, 37, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huebner, G.R.; Turlington, E.G. So-called traumatic (hemorrhagic) bone cysts of the jaws. Review of the literature and report of two unusual cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1971, 31, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaugars, G.E.; Cale, A.E. Traumatic bone cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral. 1987, 63, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortell-Ballester, I.; Figueiredo, R.; Berini-Aytés, L.; Gay-Escoda, C. Traumatic bone cyst: A retrospective study of 21 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2009, 14, E239–E243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beasley, J.D., III. Traumatic cyst of the jaws: Report of 30 cases. J Am Dent Assoc 1976, 92, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olech, E.; Sicher, H.; Weinmann, J.P. Traumatic mandibular bone cysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1951, 4, 1160–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñarrocha-Diago, M.; Sanchis-Bielsa, J.M.; Bonet-Marco, J.; Minguez-Sanz, J.M. Surgical treatment and follow-up of solitary bone cyst of the mandible: A report of seven cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001, 39, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devenney-Cakir, B.; Subramaniam, R.M.; Reddy, S.M.; Imsande, H.; Gohel, A.; Sakai, O. Cystic and cystic-appearing lesions of the mandible: Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011, 196 (Suppl. 6), WS66–WS77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szerlip, L. Traumatic bone cysts. Resolution without surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1966, 21, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapp, J.P.; Stark, M.L. Self-healing traumatic bone cysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1990, 69, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suei, Y.; Taguchi, A.; Tanimoto, K. Simple bone cyst of the jaws: Evaluation of treatment outcome by review of 132 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007, 65, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2013 by the author. The Author(s) 2013.

Share and Cite

Ahlers, E.; Setabutr, D.; Garritano, F.; Adil, E.; McGinn, J. Pathologic Fracture of the Mandible Secondary to Traumatic Bone Cyst. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2013, 6, 201-204. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1343782

Ahlers E, Setabutr D, Garritano F, Adil E, McGinn J. Pathologic Fracture of the Mandible Secondary to Traumatic Bone Cyst. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2013; 6(3):201-204. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1343782

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhlers, Eric, Dhave Setabutr, Frank Garritano, Eelam Adil, and Johnathan McGinn. 2013. "Pathologic Fracture of the Mandible Secondary to Traumatic Bone Cyst" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 6, no. 3: 201-204. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1343782

APA StyleAhlers, E., Setabutr, D., Garritano, F., Adil, E., & McGinn, J. (2013). Pathologic Fracture of the Mandible Secondary to Traumatic Bone Cyst. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 6(3), 201-204. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1343782