Abstract

A case of an ameloblastic carcinoma with extension to the anterior skull base as a result of prolonged misdiagnosis is being presented. Radical surgery and radiotherapy was performed due to involvement of the ethmoidal air sinuses and close proximity to the cranial fossa. Diagnostic tests showed no evidence of metastasis. The patient was treated with surgery, adjuvant radiotherapy, and prosthetic rehabilitation.

Keywords:

ameloblastic carcinoma; ethmoids; base of skull; radiotherapy; prosthesis; radical surgery; epiphora; maxilla Ameloblastic carcinoma (AC) was first described by Robinson [1]. According to definition, this neoplasm demonstrates features of ameloblastoma both in the primary lesion and in any metastatic growth. Thus the histological features of benign ameloblastoma may be found in AC arising from an ameloblastoma [2]. It may develop de novo (primary type) or by malignant transformation of an ameloblastoma (secondary type) with a distinction between carcinoma ex intraosseous ameloblastoma and carcinoma ex peripheral ameloblastoma [1,3].

AC, metastasizing ameloblastoma, primary intraosseous carcinoma, ghost cell odontogenic carcinoma, and clear cell odontogenic carcinoma are included in the odontogenic carcinomas. Clinical studies of eight cases by Corio et al. in 1987 found the commonest signs of AC to be swelling, pain, rapid growth, trismus, and dysphonia with radiographic resemblance to ameloblastomas, although some exhibit focal radiopacities (possibly reflecting dystrophic calcification) [4].

This case has significance in demonstrating that the “silent spread” of the rare AC, which involves the maxilla, can easily go undetected by an unsuspecting dentist or surgeon treating the lesion as a dental abscess. Clinical vigilance and a high index of suspicion are needed.

Case Report

A 74-year-old black woman presented to our maxillofacial and oral surgery department in February 2010. She complained of a swelling on the left side of her face, difficulty breathing through the left nostril, loose left upper molar teeth, tearing in the left eye, difficulty chewing, postnasal drip, and a tingling sensation that she described as a “funny feeling” over the maxillary swelling. The swelling had started about 6 months previously as a small nodule on the alveolar buccal surface of the left maxilla. This swelling, she said, grew gradually larger with a sudden recent growth spurt. She gave a history of having consulted other dentists as well as medical practitioners with no remission of the problem. The swelling was being treated as a dental abscess. Medical history revealed no significant abnormalities. Social history was noncontributory.

Extraoral examination showed a diffuse swelling over the left maxilla with a slight elevation of the left alae of the nose. Inspection of the left nostril showed an obstruction of the nasal passage by a mucosa-like mass. There was paresthesia over the distribution of the left infraorbital nerve. The patient appeared well orientated and in good health. Intraoral examination showed an expansile nonfluctuant mass of the left maxilla with vestibular obliteration and mobile molar teeth (Figure 1A,B). Neurosurgical opinion reported no neurological deficit.

Figure 1.

(A) Extraoral view of swelling. (B) Intraoral view of swelling.

Investigations

Routine blood investigations included complete blood count, urea and electrolytes, and liver function tests. These were within normal limits. HIV testing was nonreactive. Intraoral incisional biopsy done under local anesthetic was reported as an AC.

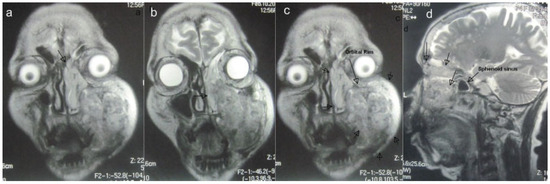

Imaging studies included an orthopantomograph and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; Figure 2A–D), which revealed a destructive lesion involving the maxillary basal bone, the maxillary sinus with breach of its walls, and the left anterior and posterior ethmoidal air cells that crossed the midline without involvement of the cranial cavity. A metastatic workup included bone scanning, which revealed no evidence of metastasis. The floor of the left orbit was abutted but not breached.

Figure 2.

(A to D) Magnetic resonance images: coronal and sagittal views indicating extent of lesion (arrows).

An impression of the maxilla was taken for the construction of an acrylic plate to be used for temporary intraoperative coverage of the anticipated defect left behind by the surgery.

Treatment

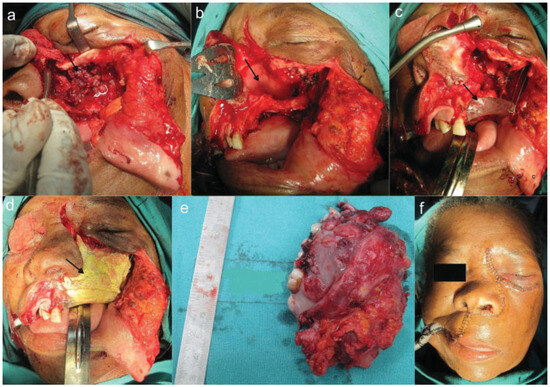

The tumor was resected under general anesthesia via a Weber-Ferguson incision. The left lateral wall of the nose and lacrimal duct and sac were sacrificed due to tumor involvement. The involved ethmoidal cells were resected until clear margins were visualized. Extraoral closure of the incision wound was achieved (Figure 3A,B,E,F).

Figure 3.

(A) Lesion. (B) Nasal septum. (C) Acrylic plate in situ. (D) Bismuth iodide paraffin paste pack in situ and closure.

The defect left behind by the tumor was packed with bismuth iodide paraffin paste–impregnated ribbon gauze and held in place by the prefabricated acrylic plate with the aid of screws and suspension wires to stimulate granulation (Figure 3C,D).

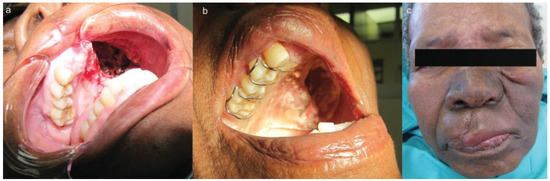

At the 1- and 2-week reviews, the patient’s wounds were healing well, with evidence of granulation tissue formation within the defect and a stable acrylic plate in situ (Figure 4A,B). The patient was then referred to the oncology department for planned radiotherapy, which was completed successfully with the prescribed linear accelerator (LA) type of radiotherapy of 25 fractions × 65 Gy over a 1-month period. Many types of LA radiotherapy are delivered using a machine called a “linear accelerator”. External-beam radiotherapy is most often delivered in the form of photon beams (either X-rays or gamma rays). A photon is the basic unit of light and other forms of electromagnetic radiation. It can be thought of as a bundle of energy. The amount of energy in a photon can vary. For example, the photons in gamma rays have the highest energy, followed by the photons in X-rays. Patients usually receive external-beam radiotherapy in daily treatment sessions over the course of several weeks [5].

Figure 4.

(A) Postoperative intraoral view showing the defect with granulation tissue. (B) Postoperative view with plate in situ 1 week later. (C) Postradiation view showing skin pigmentation.

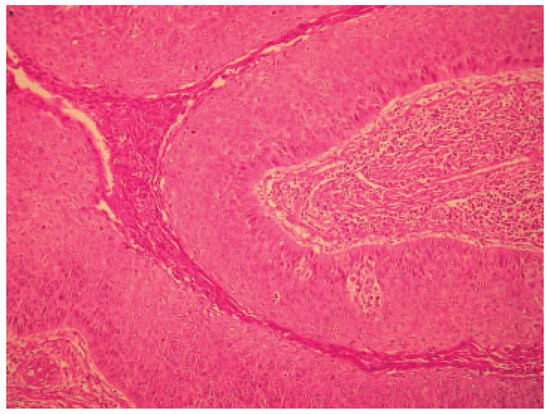

The patient was reviewed postradiotherapy at our department and found to be in good health except for pigmentation over the areas irradiated, mucositis, difficulty swallowing, and epiphora involving the left eye (Figure 4C). Future planning included regular reviews at our maxillofacial department, referral to the ear, nose, and throat department for management of the epiphora involving the left eye jointly with the ophthalmologists, and a further referral to the department of plastic surgery for possible flap surgery to aid in closure of the defect. Should the mucositis persist, an oral medicine consult would be sought. An acrylic obturator has since been constructed to assist with chewing, swallowing, and maintaining tissue support of the cheek. Histopathology report of the resected specimen confirmed the lesion as being an AC (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Micrograph of lesion.

Discussion

The characterization of carcinoma arising centrally within the mandible and the maxilla is an uncommon but complex problem [6]. AC is described in the updated World Health Organization classification as a rare malignant lesion with clinically aggressive behavior [2,7,8]. Ameloblastomas rarely exhibit clear malignant behavior with the development of metastasis, but this does occasionally occur. In the last 20 years, these tumors have been classified as either malignant ameloblastoma or AC. Studies over the last decade ending 1984 by Akrish et al. showed a male predominance [9].

To the best of the author’s knowledge, this case report of an AC involving the maxilla is the 32nd case reported in the English literature, the last two being reported by Lucca et al. [10]. Typical in the diagnosis of AC is its propensity for rapid growth unlike the slow growth of ameloblastomas. Paresthesia is a rare occurrence in ameloblastomas but not rare in ACs. Paresthesia and perforation of the cortex are common findings in the AC as seen in this case.

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice. Adjuvant chemotherapy and or radiotherapy maybe considered depending on the extent in metastatic lesions that cannot be surgically resected [11].

Although rare, these lesions have been known to metastasize mostly to the lung or regional lymph nodes. Lung aspiration of the tumor is an added complication that could arise [10]. Because the AC is a rare tumor, little information is available in the literature, and most reported cases are either single case reports or small series of cases.

The treatment and prognosis for AC is unclear in the literature due to the rarity of this tumor. Surgical excision, with or without adjuvant radiotherapy, seems to be required for local control. Surgery is the optimal treatment, although the best approach remains controversial. As AC are rare, there is no consensus for their treatment.

Despite lack of adequate clinical data, surgery followed by radiotherapy seems to be the treatment of choice [6]. Preoperative radiotherapy has been suggested to decrease the tumor size and maybe used to treat some rapidly growing tumor before radical surgery [12].

There are limited data for the efficacy of radiotherapy. Published studies highlight that radiotherapy can induce regression but not cure [13]. The role of chemotherapy is not yet proven [14]. Radiotherapy has been contraindicated in ameloblastomas because of the perceived risk of radiation-induced malignancy [2]. However, the use of radiotherapy in ACs has been described. It has been speculated that neoadjuvant radiotherapy could assist in shrinking the lesion [8]. In a series of four patients with AC treated with radiotherapy, Philip et al. found that the disease remained fairly locally controlled after treatment without further extension [15]. Thus patients whose lesions are amenable to gross total resection should preferably be treated surgically followed by radiotherapy. Due to the close proximity of the lesion to the base of the skull, its ill-defined clinical borders, and the patient’s age, it was decided to offer the patient adjuvant radiotherapy. Not much data pertaining to radiotherapy alone for ACs has been reported. ACs are treated in the same manner as other common oral cavity carcinomas with surgery and postoperative radiotherapy [15].

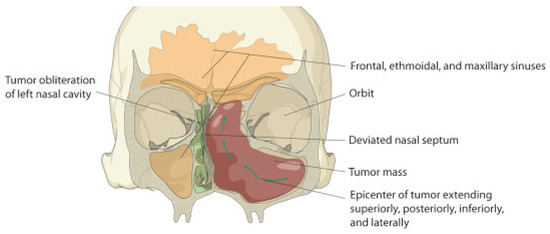

Neoadjuvant radiotherapy was not considered in this case due to the long waiting list of patients requiring radiotherapy. Delayed surgery due to prolonged waiting periods for radiotherapy allows for further destruction and spread (Figure 6) by such lesions by the tumor. The use of stereolithic technology for prosthetic reconstruction in this case was unaffordable.

Figure 6.

Diagram depicting the direction of spread of the tumor.

Conclusion

Metastatic spread of an AC is associated with a poor prognosis. Diagnosis from plain radiographs alone coupled with variations in histological presentation of solid and cystic areas can be difficult. Plain radiographs may show an ill-defined radiolucency especially in the maxilla, which can be compounded by the superimposition of the maxillary bony structures. Ultimately, the clinician is armed with essentially two tools: (1) clinical judgment and (2) imaging studies. For this reason, many authors recommend MRI as the best imaging method to assess these lesions.

Sinister spread of the tumor cephalad without bony expansion when involving the maxilla can go undetected. This is largely due to the little resistance offered by the thin maxillary bony septae. Such cases with exclusively oral manifestations are often unknowingly treated symptomatically with antibiotics, extractions, attempted incision, and drainage until significant spread of the tumor has occurred with devastating consequences.

Because of the rare occurrence of the AC in the maxilla, early diagnosis and a high index of suspicion coupled with demographic knowledge of the tumor are necessary, as the paucity of long-term clinical studies demands this. Further presentations of this nature in the interim will contribute to increasing our knowledge base of this pathological entity thus preventing mutilating surgery.

References

- Sastre, J.; Muñoz, M.; Naval, L.; Adrados, M. Ameloblastic carcinoma of the maxilla: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002, 60, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiko, Y.; Nagayasu, H.; Takeshima, M.; et al. Ameloblastic carcinoma ex ameloblastoma: Report of a case-possible involvement of CpG island hypermethylation of the p16 gene in malignant transformation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007, 103, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benlyazid, A.; Lacroix-Triki, M.; Aziza, R.; Gomez-Brouchet, A.; Guichard, M.; Sarini, J. Ameloblastic carcinoma of the maxilla: Case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007, 104, e17–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corio, R.L.; Goldblatt, L.I.; Edwards, P.A.; Hartman, K.S. Ameloblastic carcinoma: A clinicopathologic study and assessment of eight cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1987, 64, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute Fact Sheet. Available online: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Therapy/radiation (accessed on 31 March 2011).

- Dhir, K.; Sciubba, J.; Tufano, R.P. Ameloblastic carcinoma of the maxilla. Oral Oncol 2003, 39, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, E.; Bang, G. Ameloblastic carcinoma of the maxilla: A case report. J Maxillofac Surg 1986, 14, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, I.O.; Alanen, K.; Slootweg, P.J.; Salo, T. Alpha-smooth muscle actin within epithelial islands is predictive of ameloblastic carcinoma. Oral Oncol 2009, 45, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akrish, S.; Buchner, A.; Shoshani, Y.; Vered, M.; Dayan, D. Ameloblastic carcinoma: Report of a new case, literature review, and comparison to ameloblastoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007, 65, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucca, M.; D’Innocenzo, R.; Kraus, J.A.; et al. Ameloblastic carcinoma of the maxilla: A report of 2 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010, 68, 2564–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.J.; Hong, S.P.; Lee, J.I.; Lee, S.S.; Hong, S.D. Ameloblastic carcinoma: An analysis of 6 cases with review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009, 108, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardiner, D.G. Radiotherapy in the treatment of ameloblastoma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998, 17, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, R.A.; Jackson, I.T. Ameloblastic carcinoma. Report of an aggressive case and review of the literature. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1991, 19, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanham, R.J. Chemotherapy of metastatic ameloblastoma. A case report and review of the literature. Oncology 1987, 44, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, M.; Morris, C.G.; Werning, J.W.; et al. Radiotherapy in the treatment of ameloblastoma and ameloblastic carcinoma. JHK Coll Radiol 2005, 8, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the author. The Author(s) 2012.