Cleft Lip Repair: Technical Refinements for the Wide Cleft

Abstract

:Materials and Methods

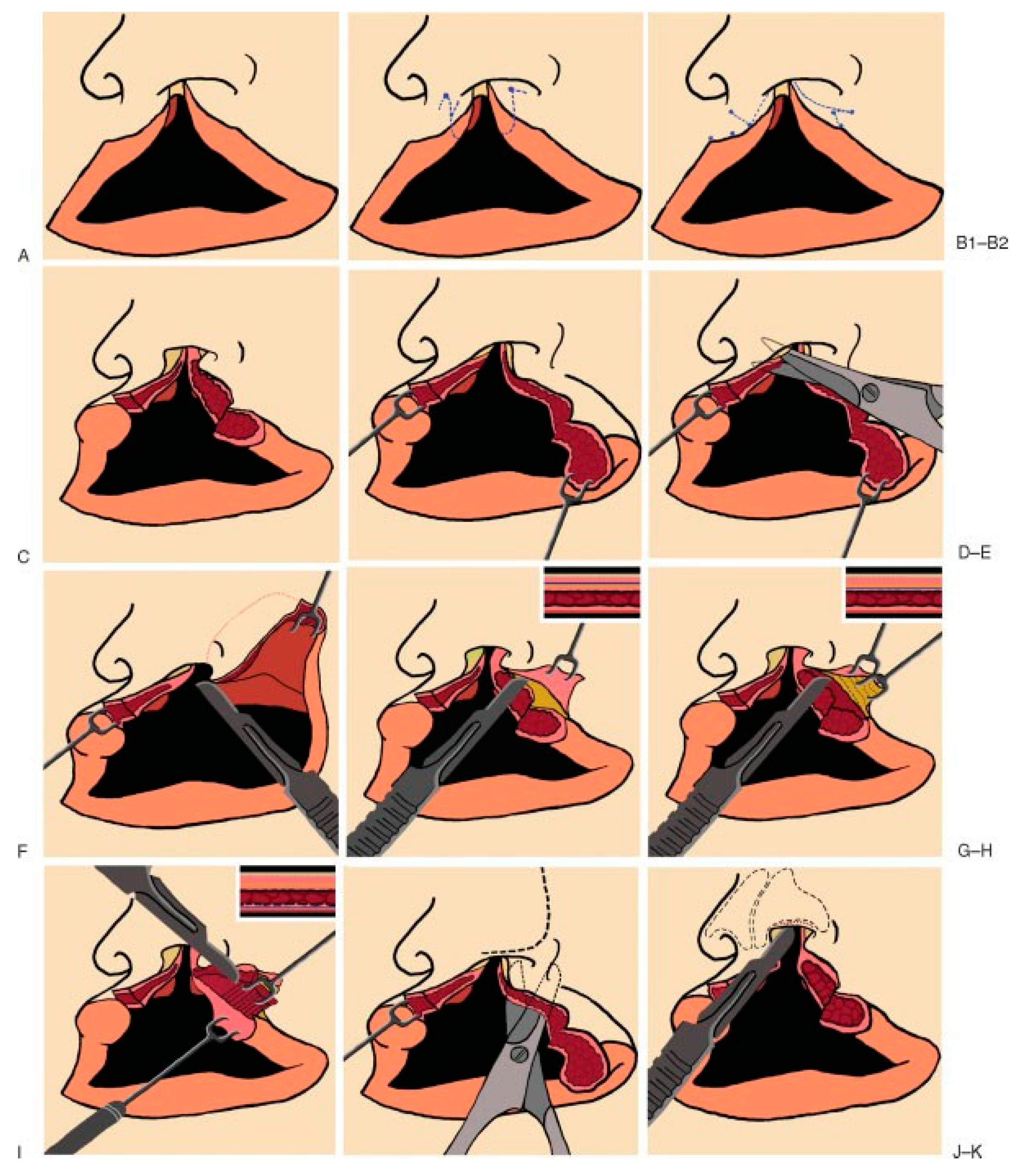

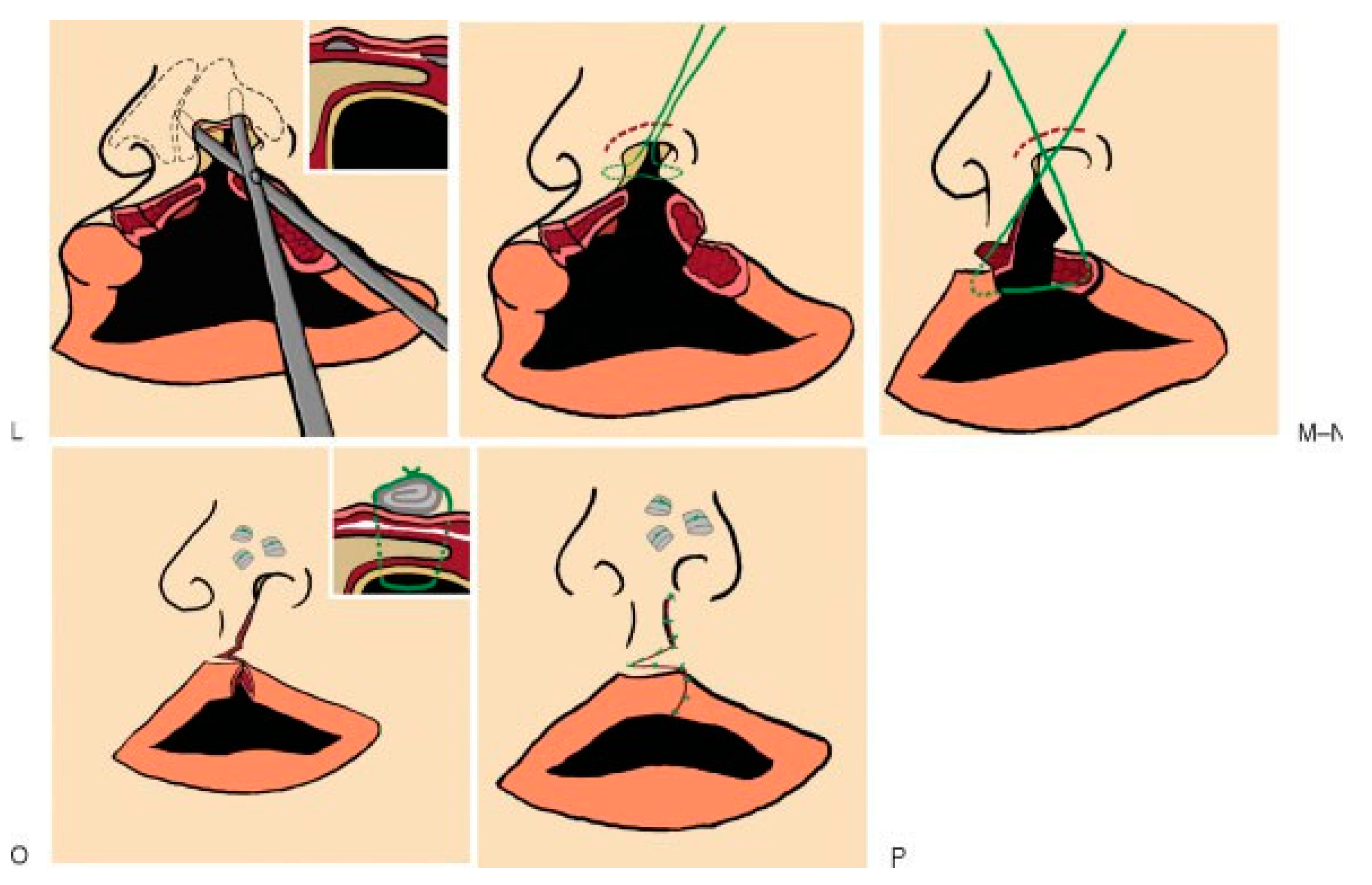

- In making the incisions, loupe magnification and incising the skin at a 90-degree angle to the skin surface to prevent dermal beveling and reduce obliquity was helpful in preventing scarring. Continually fresh 15 blade scalpels and maintenance of skin tautness were also of value during the skin incisions. Once through the dermis, beveling toward the cleft margin preserved useful tissue volume. Care was taken to avoid removing any mass from within the lip margin itself until final closure and trimming could be serially assessed. Once the incisions were made, undermining and scoring of the deep tissues to unfurl the congenital crimping was done in all cases.

- During the closure, and once the tissue layers were approximated, temporary ‘‘check sutures’’ were em-ployed so that tiny increments of tissue could be serially trimmed from both sides of the cleft, as dictated by symmetry and aesthetics. The previous undermining allowed any tension to be dissipated, leaving the dermis to heal with minimal tension, further improving results.

- Maintaining a ‘‘global view’’ of the face during and after each suture was critical to creating a natural appearing end result with good symmetry. Adjustments during closure, with undermining of distant tissues, may be necessary to achieve a natural philtral dimple, an aesthetic ‘‘pout’’, and symmetrical vermillion borders (Figure 1).

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

References

- McLeod, N.M.; Urioste, M.L.; Saeed, N.R. Birth prevalence of cleft lip and palate in Sucre, Bolivia. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004, 41, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrester, M.B.; Merz, R.D. Structural birth defects associated with oral clefts in Hawaii, 1986 to 2001. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2006, 43, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschberg, J. Functional consequences of cleft palate and its management. Orv. Hetil. 2001, 142, 1259–1263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knecht, A.K.; Bronner-Fraser, M. Induction of the neural crest: A multigene process. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002, 3, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, X.; Luukko, K.; Kettunen, P. FGF signalling in craniofacial development and developmental disorders. Oral. Dis. 2006, 12, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, R.; Bush, J.O.; Lidral, A.C. Development of the upper lip: Morphogenetic and molecular mechanisms. Dev. Dyn. 2006, 235, 1152–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, K.S.; Hong, J.P. Unilateral complete cleft lip repair: Orthotopic positioning of skin flaps. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2005, 58, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, H.P. Congenital cleft lip and plate: A muscle theory repair of the cleft lip. Ann. Surg. 1926, 84, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heycock, M.H. A field guide to cleft-lip repair. Br. J. Surg. 1971, 58, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtmann, B.; Wray, R.C. A randomized comparison of triangular and rotation-advancement unilateral cleft lip repairs. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1983, 71, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, L.G.; Posnick, J.C.; Hreczko, T.M.; Pron, G.E. Growth patterns of the nasolabial region: A morphometric study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1992, 29, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, J.A.; Bollinger, R.R. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| Tennison Repair (N ¼ 26) | Millard Repair (N ¼ 74) |

|---|---|

| Potential Advantages Offered more flexibility with wide clefts, but less with narrower clefts. This related to excellent adjustability of the volume and length of the triangular flap that can be inserted into the deficient philtrum and philtral column respectively. This allowed a less ‘‘tethered’’ appearance. Benefitted from the technical modifications (sculpturing and trimming) described in this article. Potential Problems: With growth, the repaired side sometimes lengthened. | Potential Advantages: Offered excellent results with narrow clefts, but less with wide ones. This related to the cut-as-you-go flexibility and superb aesthetics provided. With the wide cleft, however, the radian of rotation, philtral length, and volume of the advancement flap was progressively limited. Benefitted from the technical modifications (sculpturing and trimming) described in this article. Potential Problems: With growth, the repaired side and scar sometimes shortened. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2010 by the author. The Author(s) 2010.

Share and Cite

Meyer, E.; Seyfer, A. Cleft Lip Repair: Technical Refinements for the Wide Cleft. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2010, 3, 81-86. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1254377

Meyer E, Seyfer A. Cleft Lip Repair: Technical Refinements for the Wide Cleft. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2010; 3(2):81-86. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1254377

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeyer, Eric, and Alan Seyfer. 2010. "Cleft Lip Repair: Technical Refinements for the Wide Cleft" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 3, no. 2: 81-86. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1254377

APA StyleMeyer, E., & Seyfer, A. (2010). Cleft Lip Repair: Technical Refinements for the Wide Cleft. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 3(2), 81-86. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1254377