Abstract

Study Design: This is anobservational, retrospective, analytical study. Objective: The aim was todetermine a statistical basis for a future line of research based on the epidemiology of a center located in a developing country, as well as defining indirect mortality predictors. Methods: Clinical files were reviewed based on diagnosis of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10). Sociodemographic variables as well as treatment modality of the condition during hospitalization was recorded. The patient sample was divided into two groups. Student’s t-test was performed in variables with normal distribution and Chi-square test in independent random variables with standard normal distribution. For correlations, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used, taking the p-value < 0.05 as statistically significant. Results: A total of 150 participants were included in this study, from which 125 were male (83.3%). The average age was 28.58 ± 16.55 years. The median hospitalization time was 9 days. Forty-five patients (30%) were treated conservatively. Fifteen patients died during hospitalization. The factors considered as predictors of mortality in the general population corresponded to Motor Vehicle Accident, Frontonasal Duct Obstruction, Neuroinfection, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) at admission, as well as GCS at discharge. In the patients who underwent surgery, predictors of mortality corresponded to Motor Vehicle Accident, Bilateral Frontal Craniotomy, Surgical Bleeding >475 cc, Neuroinfection, as well as GCS at admission and discharge. Conclusions: The creation of adequate diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms in traumatic brain injury management is needed, especially in developing countries. More specific studies are needed, particularly analytical and multicentric studies, which may allow the development of these algorithms.

Introduction

The paranasal sinuses are pneumatized structures covered by columnar epithelium and a mucous similar to that of the cavities of the upper airway. Sinuses are structures that initiate their development during the embryonic stage; however, it is not until the second decade of life that the frontal sinus completes its formation [1,2].

Interestingly, these viscerocranium structures can present important normal anatomical variations, specifically in size and morphology, within populations that share similar ethnic and sociodemographic characteristics.

Despite the different hypotheses about their function, the one with the greatest consistency describes the security provision, given by these structures, to the encephalic substance [3].

Fractures of the facial region are recognized as relevant pathologies in terms of patient morbidity and mortality, as well as their biological, psychological, and social implications on patients and their families [1]. Among the factors involved, the ones considered to be most important are the loss of function and the damage to facial aesthetic [2]. The frontal bone is the most resistant bone of the viscerocranium, being able to withstand between 400 and 1000 kg before suffering a fracture [3]; therefore, fractures of the upper third of the face involve a greater impact mechanism than those of the other two-thirds of the face.

Frontal fractures are considered rare in terms of prevalence, as opposed to mandible or malar fractures, which constitute the most common maxillofacial fracture of this same region [4].

Morales-Olivera and collaborators have noted the lack of epidemiological studies regarding facial trauma in general; similarly, available data regarding frontal sinus fractures specifically are even scarcer [5]. On the other hand, AvelloCanisto and collaborators have indicated that this type of fracture occurs as a consequence of severe facial trauma, commonly presented as frontal impact in automobile accidents or against blunt structures [6].

The clinical manifestations of these types of fractures are variable and will depend on the encephalic or sensatory organ involvement, as well as associated facial structure damage [7]. Furthermore, the associated sequalae resulting from these fractures will vary depending on the extent of the lesion, including compromised visual, auditory, or olfactory function [8]. Therefore, a standardized, multidisciplinary, emergency approach should be prioritized as a strategy to limit short-, medium-, and long-term damage, in addition to restrict the compromise of vital structures in patients with frontal bone involvement. The developed strategies must consider the patient’s associated factors, including age, history of chronic degenerative diseases, socioeconomic status, and the environment of the incident itself (the associated mechanism of damage and the characteristics of involved motor vehicles, within other factors), as well as the promptness in referral onto a center with management capabilities in this type of fracture [9]. Furthermore, Canisto et al. have suggested clinical factors that could be associated with poor prognosis for the patient, including the intensity of the involved trauma, degree of associated brain and eye involvement, age, and delay on medical management [10].

The therapeutic approach for this type of fracture in our center has not been standardized and algorithmized. It was sought to determine the epidemiological factors, as well as indirect predictors of mortality, for epidemiological determination within our center and precedent establishment for subsequent creation of an efficient therapeutic algorithm applicable to our population.

Methods

Study Design

An analytical, observational, and retrospective study was developed, where a review of the clinical records of each individual participant was performed. Clinical, imaging, and surgical data of patients with Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) between the years 2015 and 2021 was collected. Those who presented a frontal sinus fracture with associated TBI, based on the use of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) referring to fractures of the frontal bone and frontal sinus, grouped as S0-2 [11], were included.

Patients who had a prior history of acute trauma, as well as those who underwent cranioplasty or similar interventions in a secondary instance, were excluded. Participants whose clinical records or computed tomography imaging wasn’t available were eliminated. This study was developed within the University Hospital “Dr. Jose’ Eleuterio Gonza’lez”, a single, third-level, referral medical center belonging to Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. An alphanumeric Excel database was created from compiled participant data to organize relevant information.

Finally, consent for this study was given by the Institutional Review Board of Ethics and Research Committee, with registration number PI21-00389.

Variables

Sociodemographic variables, such as age, sex, nationality, and years of schooling, were compiled. Information regarding initial clinical presentation of the patients, such as Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, presence of comorbidities such as chronic degenerative diseases, drug addictions, as well as their initial laboratories, which focused on blood biometry data, was collected.

Data regarding patient’s condition previous and posterior to medical management, such as presence of neurological focalization, cerebrospinal fluid fistula, and associated complications (e.g., infection, fever, seizures, or death), were reviewed.

Information concerning surgical management and its characteristics, such as surgery duration, time window from door to surgery initiation, type of surgery, and material used, was reviewed as well.

Sample Size

The sample was gathered by convenience method of sampling, since the studied sample corresponded to the total number of patients who were hospitalized in the authors’ center during 2015–2021.

Statistical Analysis

The sample was initially divided into two separate groups (surgical management vs non-surgical management) with the aim of determining variables of clinical significance. IBM SPSS software (version 23.012), RStudio (version 4.0.2), and the ggplot2 package were used for analysis.

To compare data between groups, Student’s t-test was utilized in variables with normal distribution, whereas Chisquare test was applied in independent random variables with standard normal distribution [12]. For correlations, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used.

A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The variables that resulted statistically significant in the univariate analysis, within the general population and in those who underwent surgery, were subjected to a multivariate logistic regression model to predict mortality.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

A total of 457 clinical records were evaluated under the requested ICD-10. A total of 150 subjects who met inclusion criteria were included. The average population age was 32.95 ± 14.48 years, being 125 (86.4%) male patients. Predominant comorbidities in our population corresponded to alcoholism, which was present in 78 patients (52%), smoking in 62 patients (41.3%), and obesity in 25 patients (16.6%). The additional comorbidities are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

General Population Characteristics.

The group who underwent any type of intervention presented a higher percentage of male participants, a lower age range, as well as a greater number of comorbidities, including toxicosis, alcoholism, smoking, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, from which smoking was found as statistically significant (Table 2). A total of 119 patients (79.3%) had a follow-up of at least 6 months in the outpatient clinic.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Population Who Underwent Surgery in Comparison to Those With Conservative Management.

Trauma Characteristics

The most common associated trauma mechanism was blunt trauma by direct assault, which includes batter with a blunt object, which represented 43 patients (28.7%), followed by trauma associated to motor vehicle accident (37 patients; 24.7%), and free fall from a distance >2 m (29 patients; 19.3%).

The main associated trauma mechanism in the interventional group corresponded to blunt trauma by direct assault, which was present in 36 patients (35%), while the main associated trauma mechanism in the non-interventional group corresponded to free fall from a distance >2 m, which was present in 17 patients (38%), both representing statistically significant variables. A detailed dissection of associated trauma mechanisms by group is represented in Table 2.

On admission evaluation, 21 patients (14%) had cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistula and 79 patients (50.3%) had neurological focalization, with no significant difference between groups. A total of 81 patients (54%) presented involvement of external and internal tables of the frontal sinus. The most common intracranial involvement corresponded to epidural hematoma, which was present in 41 patients (27.3%), from which 36 patients (34.3%) were in the interventional group. No differences were found in terms of laterality. The most common causes of mortality within our sample corresponded to Neuroinfection in 5 patients (3.3%), Intracerebral Hemorrhage in 3 patients (2%), and Epidural Hematoma in 2 patients (1.3%).

In the interventional group, involvement of both frontal sinus tables was present in 65 patients (61.9%). In the nonintervention group, the most affected table of the frontal sinus corresponded to the external table, which was presented in 25 patients (55.6%), which was statistically significant.

Nasofrontal duct obstruction was found, by computed tomography, in 71 patients (47.3%), which corresponded to less than 15% (14 patients) of the patients in the nonintervention group and more than 50% (57 patients) in the interventional group, presenting statistical significance. A greater number of depressed fractures were present in the interventionism-group, in comparison to the noninterventionism group, in which the most common pattern of fracture corresponded to linear fractures (Table 2).

Intervention Characteristics

The most common surgical approach developed in our center corresponded to bilateral frontal craniotomy, which was performed in 52 patients (49.5%). The second most common surgical approach corresponded to squirlectomy and osteosynthesis, which was performed in 33 patients (31.4%). The third most common approach corresponded to unilateral frontal craniotomy, which was performed in 17 patients (11.3%) (Table 1).

No significant differences were found between the Glasgow Coma Scale on admission and at discharge in either group or between groups. A total of 134 patients (86.4%) were transferred postoperatively to recovery room, while the rest had to be transferred previously to the intensive care unit for specialized care, where they remained for an average of 4 days (±2.1 days).

A significant difference was found when comparing days until home discharge between groups, corresponding to 9 days (7–14 days) on the intervention group and 6 days (5– 13 days) in the control group.

In the intervention group, transoperative bleeding average corresponded to 390 cc (155–600 cc), and the average surgical duration was 240 min (151.5–300 min). The most common type of surgical wound performed was the Sauter type in 51 patients (48.6%), while the most used prophylaxis antibiotic was Amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, which was administered in 80 patients (53.3%).

The most common complication developed corresponded to neuroinfection, which was developed in 7 patients (4.6%), followed by local infection (3.3%), and soft tissue infection (1.3%). No bone infection was reported.

From the initial patients who presented CSF fistula, 6 patients (4%) persisted with this pathology; thus, due to decreased CSF pressure, patients were subjected to lumbar cisternostomy, which reported a mortality rate of 15 patients (10%) during postsurgical hospitalization and 3 patients (2%) during the first 6 months of postsurgical follow-up, both in the intervention group.

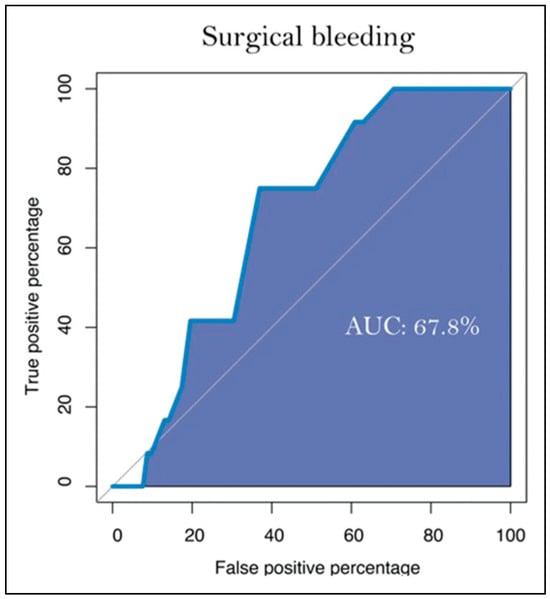

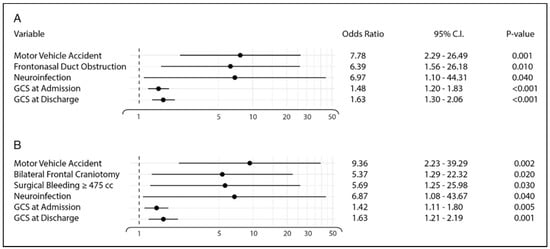

To determine the cutoff point for surgical bleeding as a predictor of mortality in our population an ROC curve was developed, which is presented in Figure 1. The developed multivariate regression model to predict mortality was controlled by age, sex, and intracranial involvement. Within the regression model in the general population, the associated predictors of mortality, which acquired statistical significance, corresponded to Motor Vehicle Accident (p = 0.001, aOR = 7.78, 95% CI 2.29–26.49), Frontonasal Duct Obstruction (p = 0.01, aOR = 6.39, 95% CI 1.56–26.18), Neuroinfection (p = 0.04, aOR = 6.97, 95% CI 1.10–44.31), GCS at Admission (p = < 0.001, aOR = 1.48, 95% CI 1.20–1.83), and GCS at Discharge (p = <.001, aOR = 1.63, 95% CI 1.30–2.06).

Figure 1.

ROC curve describing the surgical bleeding cutoff point of significance.

Alternatively, in the regression model which included the population which underwent surgical intervention, the associated predictors of mortality, which acquired statistical significance, corresponded to Motor Vehicle Accident (p = 0.002, aOR = 9.36, 95% CI 2.23–39.29), Bilateral Frontal Craniotomy (p = 0.02, aOR = 5.37, 95% CI 1.29–22.32), Surgical Bleeding ≥ than 475 cc (p = 0.03, aOR = 5.69, 95% CI 1.25–25.98), Neuroinfection (p = 0.04, aOR = 6.87, 95% CI 1.08–43.67), GCS at Admission (p = 0.005, aOR = 1.42, 95% CI1.11–1.80), and GCS at Discharge (p = 0.001, aOR = 1.63, 95%CI 1.21–2.19). The complete information of the multivariate regression models performed is displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Multivariate regression model controlled by age, sex, and intracranial involvement represented in a Forrest Plot. (A) Selected variables of the general population introduced to the multivariate regression model. (B) Selected variables of the patients who underwent surgical intervention introduced to the multivariate regression model.

Discussion

The results found in this study were consistent in comparison to similar retrospective studies and current scientific literature that have focused on frontal sinus fracture. Available literature suggests that this type of fracture presents in males with more frequency than females. In our study, male population represented more than 85% of our sample, which is a similar male prevalence reported by Stephen et al. [13] in 2005, with 88% of males. Likewise, other similar studies report a male prevalence of more than 70% [13,14,15,16,17].Our study also reported an age average of 32.95 ± 14.48 years, which is slightly lower than the reported age average in American literature, where the 35–45-year-old age group corresponded to the most affected [16].

The most common mechanism of trauma within our population was blunt trauma by direct assault, which differs from other centers most common mechanism, as reported by Torres-Criollo et al. [17] in 2020. This inconsistency in the type of mechanism with reported literature may be associated to exclusive evaluation and report of depressed skull fractures within the population of the previous study.

Furthermore, infection has been established as the most common complication associated with this type of fracture, while neuroinfection is the most feared associated complication. Loannides et al. [18] reported a similar percentage of neuroinfection as in our population, although neuroinfection rate has been estimated to develop in, approximately, 6% of patients with this condition [18,19].

Swinson et al. [20] propose that the materials utilized within the surgical intervention for correction of structural defects produced by trauma may vary according to surgeons and centers preference and availability but emphasizing that bone grafting should be preferred over other types of materials. In our center, similar to Owens et al. [21] autologous pericranial grafting was the most used material for correction of structural defects. The usage of this material is preferred within our center because of the absence of economic resources and additional materials.

On their population, Bell et al. [22] reported an average hospitalization of 8.9 days, which is similar to our

Population, with 9 days of follow-up. Notably, most of their patients did not require surgical management and were consequently treated conservatively, which differs from our management distribution. In their associated fracture mechanism, trauma associated with motor vehicle accident and blunt trauma by direct assault were listed within the most common causes. For their surgical management, similar to our center, autologous pericranial grafting was considered as the preferred material and systematically used. Regarding their mortality and complication rate, its percentages were relatively low (5.1% and 6.9%, respectively), which can be associated with the existence of a previously established surgical protocol for these types of fractures within their institution, thus, demonstrating the importance of the creation and standardization of surgical protocols for an adequate management of frontal sinus fractures.

Our study findings are similar to those reported outside of Mexico, therefore, serving as an epidemiological and surgical reference in developing countries such as our own. However, we identified a variation in management selection in comparison to other authors, where clinical observation is preferred over intervention with the goal of frontal sinus preservation, suggesting that surgical management of frontal sinus fracture should be employed exclusively if nasofrontal duct obstruction, CSF leakage, or threatening intracranial involvement is present. This management selection, in addition to the recommendation of prophylactic antibiotic usage, may result in the reduction of mortality and complication rate in short and long term [23,24,25,26].

Another management possibility in frontal sinus fractures, as described by Jing et al. [27] is the usage of cranialization in cases of comminuted fractures of the posterior table. At our center, cranialization was performed in most of the patients within the interventionist group due to the complexity of these cases. In a clinical study conducted in Brazil, the described prevalence of nasofrontal duct obstruction corresponded to 2 patients (6.8%), which notably differs from our population, where 71 patients (47.3%) presented this associated complication. Additionally, their intracranial involvement, considering hemorrhages and hematomas, corresponded to 54.2%, which slightly contrast with our population intracranial involvement (46%) [28].

An additional clinical study developed in Mexico, which included 20 patients with frontal sinus fractures who were non-surgically managed, implied that a non-interventionist management, when selected with an individualized approach, may be a feasible treatment modality, although it may as well be associated with complications, such as CSF leakage and frontal abscesses, in approximately 20% of patients. These results are considerable; however, it is important to consider that trauma mechanism as well as intracranial involvement is not depicted. Additionally, only a limited number of patients have long-term follow-up [29]. Alternatively, in another Mexican study in which surgical management of frontal sinus fractures was exclusively evaluated, it was determined that their main associated fracture mechanisms corresponded to blunt trauma by direct assault from a third party on a public road, which is consistent with our population. The most associated fracture corresponded to an orbital fracture. While the surgical approach within this population was not specified, it concluded in cranialization of the frontal sinus [30].

When evaluating the 15 deceased patients within our intervention group, we recognized a higher prevalence of associated factors, such as an associated high-power trauma mechanism (trauma associated to motor vehicle accident), an extensive surgical approach (bilateral frontal craniotomy), presence of nasofrontal duct obstruction, a transsurgical bleeding greater than 475 milliliters, as well as postsurgical infection.

Within our regression model, it was evidenced that the presence of clinical factors, associated trauma mechanism, as well as the development of specific surgical approaches, may predispose suboptimal clinical outcomes and mortality, thus, suggesting that an adequate evaluation of the clinical and non-clinical characteristics could be of importance when estimating mortality as an outcome in patients who have traumatic brain injury with associated frontal sinus fractures. Nevertheless, additional prospective studies are needed to establish adequate evaluation protocols of patients with facial trauma, as well as feasible and secure surgical algorithms, within lowand middle-income countries.

The limitations of the present study are in its methodological composition, being a descriptive, observational, and retrospective study. It is of importance to remark the necessity of further prospective, analytical, and multicentric studies, which may allow further evaluation of relevant prognostic factors, in addition to discern adequate management algorithms, consequently, improving the existing limitations within this study. Additionally, it is important to note that the current study did not account for concomitant injuries in our patients, potentially serving as a confounding factor. This omission underscores the need for caution when interpreting the study results, as the presence of additional injuries alongside the primary focus may introduce complexities that could influence the observed outcomes. Furthermore, it is imperative to acknowledge that the elevated odds ratio identified in the current study for certain interventions may be associated with selection bias. This observation stems from the propensity for more invasive surgical approaches to be employed in cases characterized by severe traumatic injuries. It is crucial to interpret these findings in the context of patient selection, where the severity of trauma may influence the choice of interventions, thereby impacting the observed odds ratios. Careful consideration of the clinical nuances surrounding traumatic brain injuries and frontal sinus fractures is essential for a comprehensive understanding of the study results.

Conclusions

Frontal sinus fractures are, although uncommon, a clinically relevant type of fracture commonly produced from a highenergy traumatic injury, which associates with significant morbidity and mortality.

Current scientific literature regarding frontal sinus fractures, as well as their clinical and management characteristics, is scarce and generally focused on accompanied facial fractures of the intermediate and lower third of the viscerocranium, which, in comparison, are more common.

An adequate evaluation of the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with frontal sinus fractures within tertiary level centers may promote the development of greater clinical studies, which may elucidate the common associated pathogenesis, pathological factors which could promote poor clinical outcomes, as well as the adequate management pathway considering patient-specific characteristics.

Continuous efforts in facial trauma should be promoted, especially within institutions that evaluate and manage this type of fracture without a stablished therapeutic algorithm. Further development of clinical studies focused on frontal sinus fractures will promote the comprehension of this pathology, which, additionally, may facilitate the generation of standardized, evidence-based, therapeutic algorithms which consider patient-specific clinical and epidemiological factors. The creation of this type of patient-specific therapeutic algorithms may associate with better clinical outcomes in patients with frontal sinus fractures.

Author’s Notes

Previous Presentations: Poster presentation at “Congreso de Neurocirug’ıa del Noreste” of the “Sociedad de Cirug’ıa Neurológica” of Mexico, where it obtained the second place in its category. Poster presentation at “32° Congreso Nacional de Investigación e Innovación en Medicina”, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Mexico. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of the current article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional Review Board and Ethics and Research Committee with registration number PI21-00389.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of the current article.

References

- Avello Canisto, F.; Avello Peragallo, A. Nueva clasificación de las fracturas del tercio superior facial: Consideraciones anatomo-quiru’rgicas. An. Fac. Med. 2013, 4, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasileiro, B.F.; Passeri, L.A. Epidemiological analysis of maxillofacial fractures in Brazil: A 5-year prospective study. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2006, 1, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MarKnez-Villalobos Castillo, S. Osteos’ıntesis Craniomaxilofacial; Ergon: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- El Khatib, K.; Danino, A.; Malka, G. The frontal sinus: A culprit or a victim. A review of 40 cases. J. Cranio-Maxillo-Fac. Surg. 2004, 5, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Olivera Mart’ın, J.; Herna’ndez-Ordoñez, R.; Pacheco-López, R. “Estudio epidemiológico del trauma facial en el servicio de cirug’ıa pla’stica y reconstructiva del hospital general «Dr. Rube’n Leñero» en la Ciudad de Me’xico. Incidencia de 5 años”. Cirug’ıa Pla’stica. 2017, 3, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Avello Canisto, F.; Saavedra Leveau, J.; Pasache Jua’rez, L.; Iwaki Cha’vez, R.; Nu’ñez Castañeda, J.; Robles Hermenegildo, M. Fracturas del tercio superior facial: Experiencia en el Servicio de Cirug’ıa de Cabeza, Cuello y Ma’xilo-Facial del Hospital Nacional Dos de Mayo, 1999–2009. An Fac Med. 2014, 75, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Avello, F. Epidemiolog’ıa y clasificación de las fracturas ma’xilo-faciales. Hosp. Nac. Dos de Mayo. Tesis de especialidad en Cirug’ıa de Cabeza, Cuello y Ma’xilo-Facial; Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Facultad de Medicina: Lima, Peru, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Manolidis, S.; Hollier, L.H., Jr. Management of frontal sinus fractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007, 120 (Suppl. 7), 32S–48S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Levin, L.; Goldman, S.; Peled, M. Dento-alveolar and maxillofacial injuries-a retrospective study from a level 1 trauma center in Israel. Dent. Traumatol. 2007, 23, 155–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canisto, F.A. Clasificación de las Fracturas Faciales en el Servicio de Cirug’ıa de Cabeza, Cuello y Ma’xilo-Facial del Hospital Nacional “Dos de Mayo”, 1999–2014. Revista Me’dica Carriónica. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. In Fractures of Skull and Facial Bone. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision; Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, E.; Metzinger, M.; Guerra, A.; Eloy, R. Frontal sinus fractures: Management guidelines. Facial Plast. Surg. 2005, 21, 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Hachl, O.; Tuli, T.; Schwabegger, A.; Gassner, R. Maxillofacial trauma due to work-related accidents. Nt J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2002, 31, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Putnam, M.; Feustel, P.; Koltai, P. The age dependent relationship between facial fractures and Skull fractures. Int. J. Ped Orl. 2004, 68, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonza’lez, E.; Pedemonte, C.; Vargas, I.; et al. Fracturas facialesen un centro de referencia de traumatismos nivel I: Estudio descriptivo. Rev. Española Cirug’ıa Oral. Maxilofac. 2015, 37, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Criollo, L.; Diaz, P.; Mancheno-Benalcazar, K.; et al. Management of cranial fractures with sinking Manejo de fracturas creaneales con hundimiento. Arch. Venez. Farmacol. Ter. 2021, 39, 760–765. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannides, C.; Freihofer, H.P.; Vrieus, J.; Friens, J. Fractures of the frontal sinus: A rationale of treatment. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1993, 3, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sataloff, R.T.; Sariego, J.; Myers, D.L.; Richter, H.J. Surgical management of the frontal sinus. Neurosurgery. 1984, 15, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinson, B.D.; Jerjes, W.; Thompson, G. Current practice in the management of frontal sinus fractures. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2004, 12, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, M.; Klotch, D.W. Use of bone for obliteration of the nasofrontal duct with the osteoplastic flap: A cat model. Laryngoscope 1993, 103, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, R.B.; Dierks, E.J.; Brar, P.; Potter, J.K.; Potter, B.E. A protocol for the management of frontal sinus fractures emphasizing sinus preservation. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 5, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavana, K.; Kumar, R.; Keshri, A.; Aggarwal, S. Minimally invasive technique for repairing CSF leaks due to defects of posterior table of frontal sinus. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base. 2014, 3, 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy, J.L.; Molendijk, J.; Reddy, S.K.; et al. Severe infectious complications following frontal sinus fracture: The impact of operative delay and perioperative antibiotic use. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 1, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, R.A.; Hill JLJr Davenport, D.L.; Snow, D.C.; Vasconez, H.C. Cranialization in a cohort of 154 consecutive patients with frontal sinus fractures (1987–2007): Review and update of a compelling procedure in the selected patient. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2013, 1, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, M.A.; Tatum, S.A. Frontal sinus fractures: Evolving clinical considerations and surgical approaches. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma. Reconstr. 2019, 2, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, X.L.; Luce, E. Frontal sinus fractures: Management and complications. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma. Reconstr. 2019, 3, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montovani, J.C.; Nogueira, E.A.; Ferreira, F.D.; Lima Neto, A.C.; Nakajima, V. Surgery of frontal sinus fractures. Epidemiologic study and evaluation of techniques. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2006, 2, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafa’n-Quiroga, R.; Cienfuegos-Monroy, R.; Sierra-Mart’ınez, E. Fractures of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus: Nonsurgical management and complications. Cir. Cir. 2010, 5, 387–392. [Google Scholar]

- Rodr’ıguez-Perales, M.A.; Canul-Andrade, L.P.; Villagra-Siles, E. (Eds.) Tratamiento Quiru’rgico de las Fracturas del Seno Frontal; Anales de Otorrinolaringolog’ıa Mexicana: Merida, Mexico, 2004. [Google Scholar]

© 2024 by the authors. The Author(s) 2024.