The Versatility of the Supraclavicular Flap for Head and Neck Reconstruction

Abstract

Introduction

Material and Methods

Results

Complications

Donor Area

Recipient Area

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nikolaidou, E.; Pantazi, G.; Sovatzidis, A.; et al. The supraclavicular artery island flap for pharynx reconstruction. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamberty, B.G. The supra-clavicular axial patterned flap. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1979, 3, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallua, N.; Machens, H.G.; Rennekampff, O.; et al. The fasciocutaneous supraclavicular artery island flap for releasing postburn mentosternal contractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1997, 7, 1878–1884, discussion 1885–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabulut, B. Supraclavicular flap reconstruction in head and neck oncologic surgery. J. Craniofac Surg. 2020, 4, e372–e375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamidian Jahormi, A.; Horen, S.R.; Miller, E.J.; et al. A comprehensive review on the supraclavicular flap for head and neck reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2022, 6, e20–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, W.; Cao, G.; et al. Pedicled supraclavicular artery island flap versus free radial forearm flap for tongue reconstruction following hemiglossectomy. J. Craniofac Surg. 2015, 26, e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, H.R.N.; de Faria, J.C.M.; Dos Santos, R.V.; et al. Supraclavicular flap as a salvage procedure in reconstruction of head and neck complex defects. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2019, 72, e9–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welz, C.; Canis, M.; Schwenk-Zieger, S.; et al. Oral cancer reconstruction using the supraclavicular artery island flap: Comparison to free radial forearm flap. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 2261–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atallah, S.; Guth, A.; Chabolle, F.; et al. Supraclavicular artery island flap in head and neck reconstruction. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol Head. Neck Dis. 2015, 132, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, D.; et al. Clinical application of supraclavicular flap for head and neck reconstruction. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2019, 276, 2319–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, A.S.; Wright, M.J.; Johnston, S.; et al. The use of multislice CT angiography preoperative study for supraclavicular artery island flap harvesting. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2012, 69, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Cho, H.M.; Kim, J.K.; et al. The supraclavicular artery island flap: A salvage option for head and neck reconstruction. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 40, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nthumba, P.M. The supraclavicular artery flap: A versatile flap for neck and orofacial reconstruction. J. OralMaxillofac Surg. 2012, 70, 1997–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, E.S.; Liu, P.H.; Friedlander, P.L. Supraclavicular artery island flap for head and neck oncologic reconstruction: Indications, complications, and outcomes. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009, 124, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shires, C.B.; Sebelik, M. The submental flap: Be wary. Clin. Case Rep. 2022, 1, e05260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age | Sex | Reconstruction (Primary/Secondary) | Complication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 65 | Male | Primary. Cutaneous reconstruction parotid region | Salivary fistula |

| Patient 2 | 70 | Male | Secondary. Plate exposure | No |

| Patient 3 | 74 | Female | Primary. Tongue reconstruction | Cervical fistula and neck infection |

| Patient 4 | 62 | Male | Secondary. Bone exposure | Suture dehiscence in donor site |

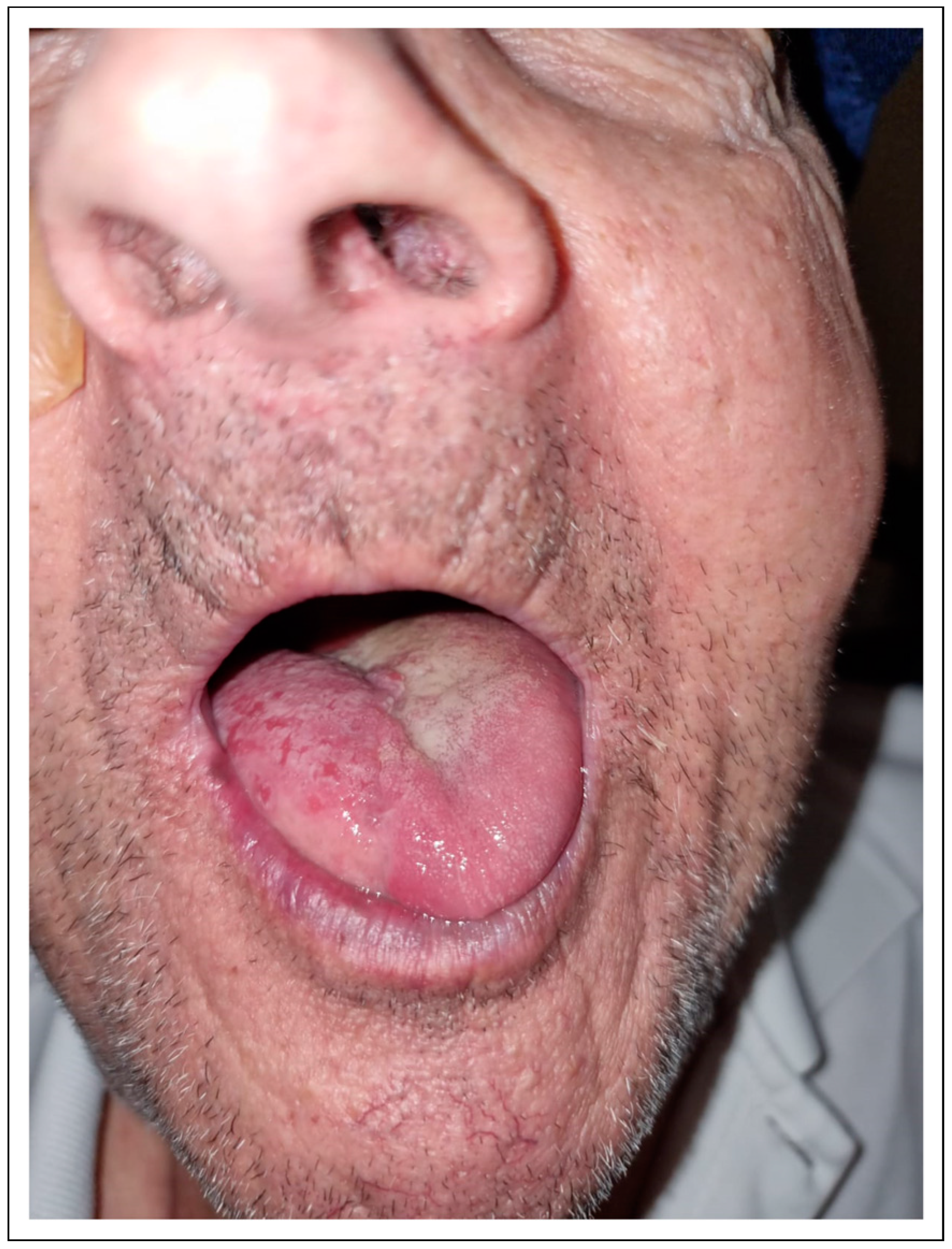

| Patient 5 | 80 | Male | Primary. Tongue reconstruction | No |

| Patient 6 | 81 | Male | Secondary. Plate exposure | Shoulder septic arthritis |

| Patient 7 | 62 | Female | Primary. Cheek defect reconstruction | Cervical fistula and neck infection |

| Patient 8 | 63 | Female | Secondary. Plate exposure | No |

| Patient 9 | 73 | Male | Primary. Tongue reconstruction | Cervical fistula and neck infection |

| Patient 10 | 70 | Male | Primary. Cutaneous reconstruction parotid region | Suture dehiscence in donor site |

| Patient 11 | 74 | Male | Primary. Cutaneous reconstruction parotid region | No |

| Patient 12 | 76 | Male | Secondary. Plate exposure | No |

| Patient 13 | 74 | Female | Secondary. Plate exposure | |

| Patient 14 | 80 | Male | Primary. Cutaneous reconstruction parotid region | No |

| Patient 15 | 75 | Male | Primary. Cervical cutaneous metastasis | No |

| Patient 16 | 71 | Female | Secondary. Bone exposure | Suture dehiscence in donor site |

| Patient 17 | 72 | Male | Secondary. Plate exposure | No |

© 2024 by the authors. The Author(s) 2024.

Share and Cite

Imanol, Z.I.; Leonardo, F.; Paolo, C.; Fernando, M.; Ildefonso, M.L. The Versatility of the Supraclavicular Flap for Head and Neck Reconstruction. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2024, 17, 306-313. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875241226535

Imanol ZI, Leonardo F, Paolo C, Fernando M, Ildefonso ML. The Versatility of the Supraclavicular Flap for Head and Neck Reconstruction. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2024; 17(4):306-313. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875241226535

Chicago/Turabian StyleImanol, Zubiate Illarramendi, Ferrari Leonardo, Cariati Paolo, Monsalve Fernando, and Martínez Lara Ildefonso. 2024. "The Versatility of the Supraclavicular Flap for Head and Neck Reconstruction" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 17, no. 4: 306-313. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875241226535

APA StyleImanol, Z. I., Leonardo, F., Paolo, C., Fernando, M., & Ildefonso, M. L. (2024). The Versatility of the Supraclavicular Flap for Head and Neck Reconstruction. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 17(4), 306-313. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875241226535