Evaluating Facial Trauma in the Amish: A Study of a Unique Patient Population

Abstract

Introduction

Materials and Methods

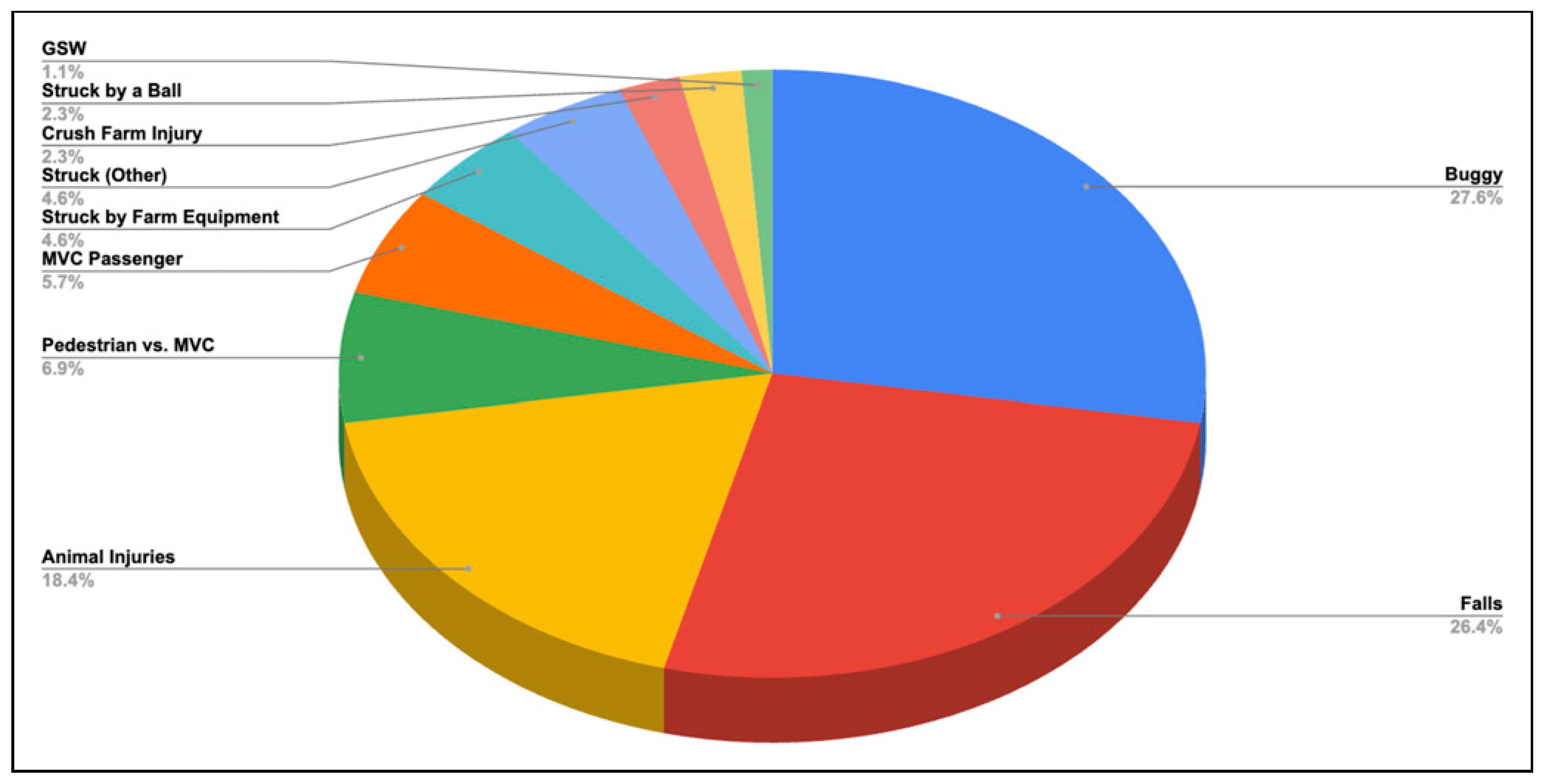

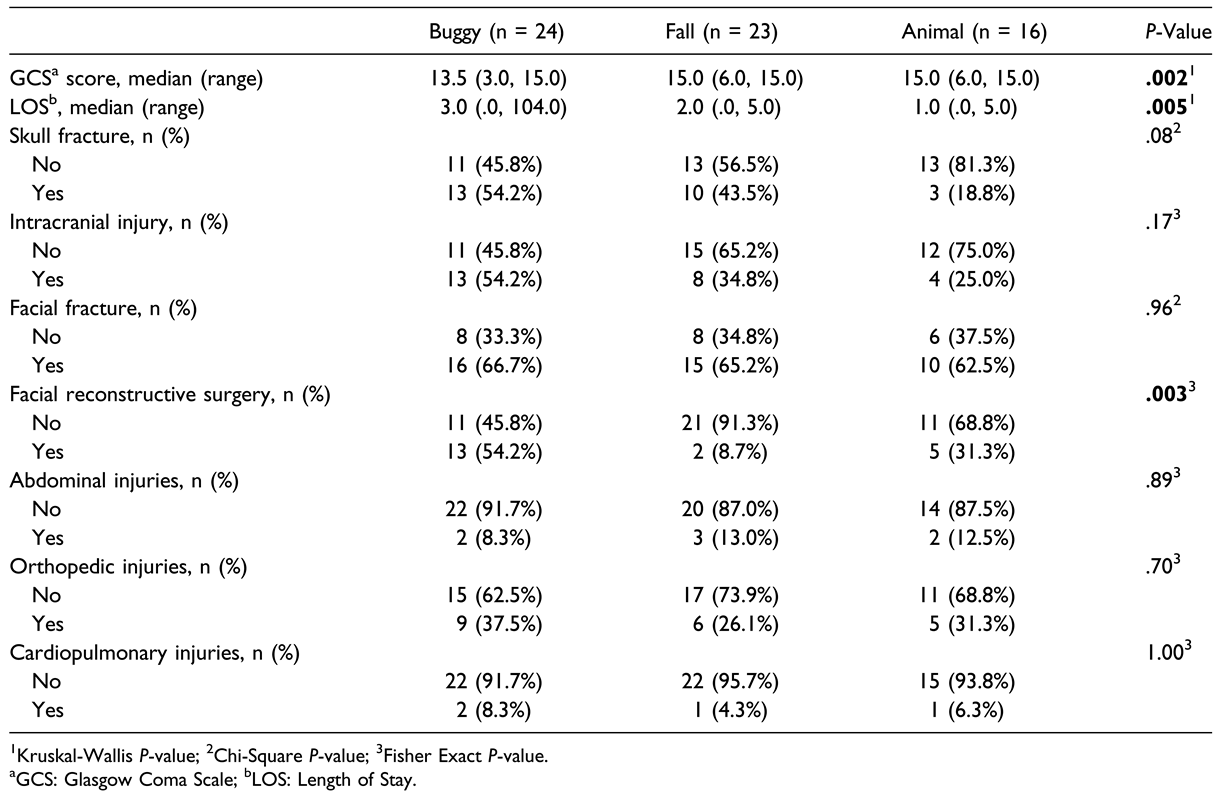

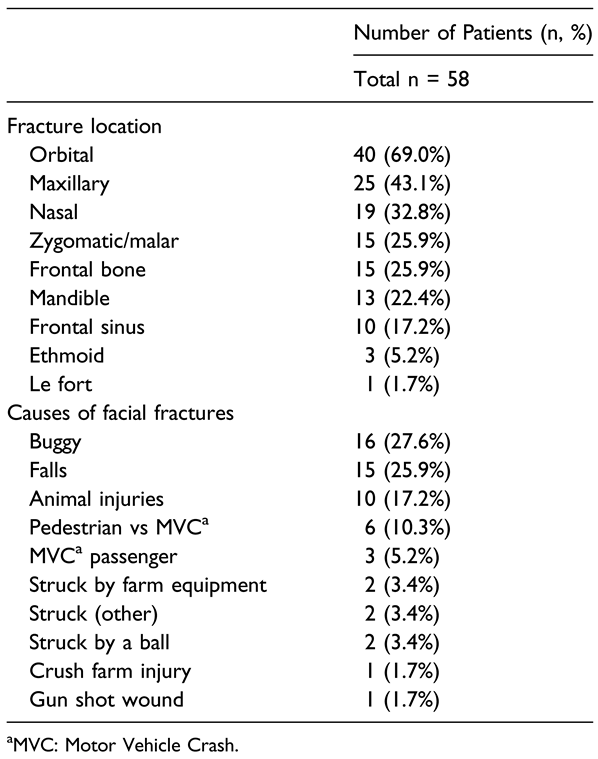

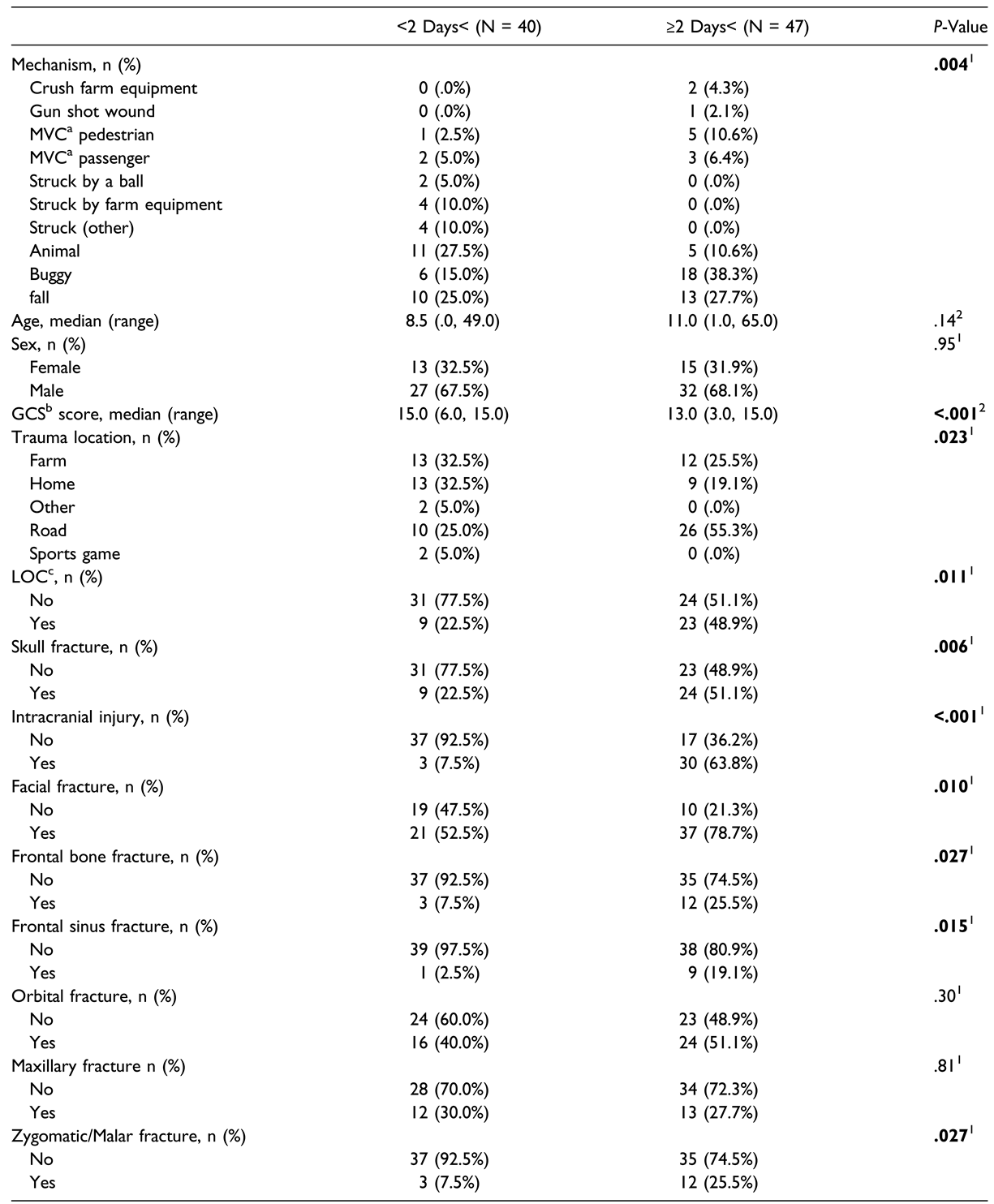

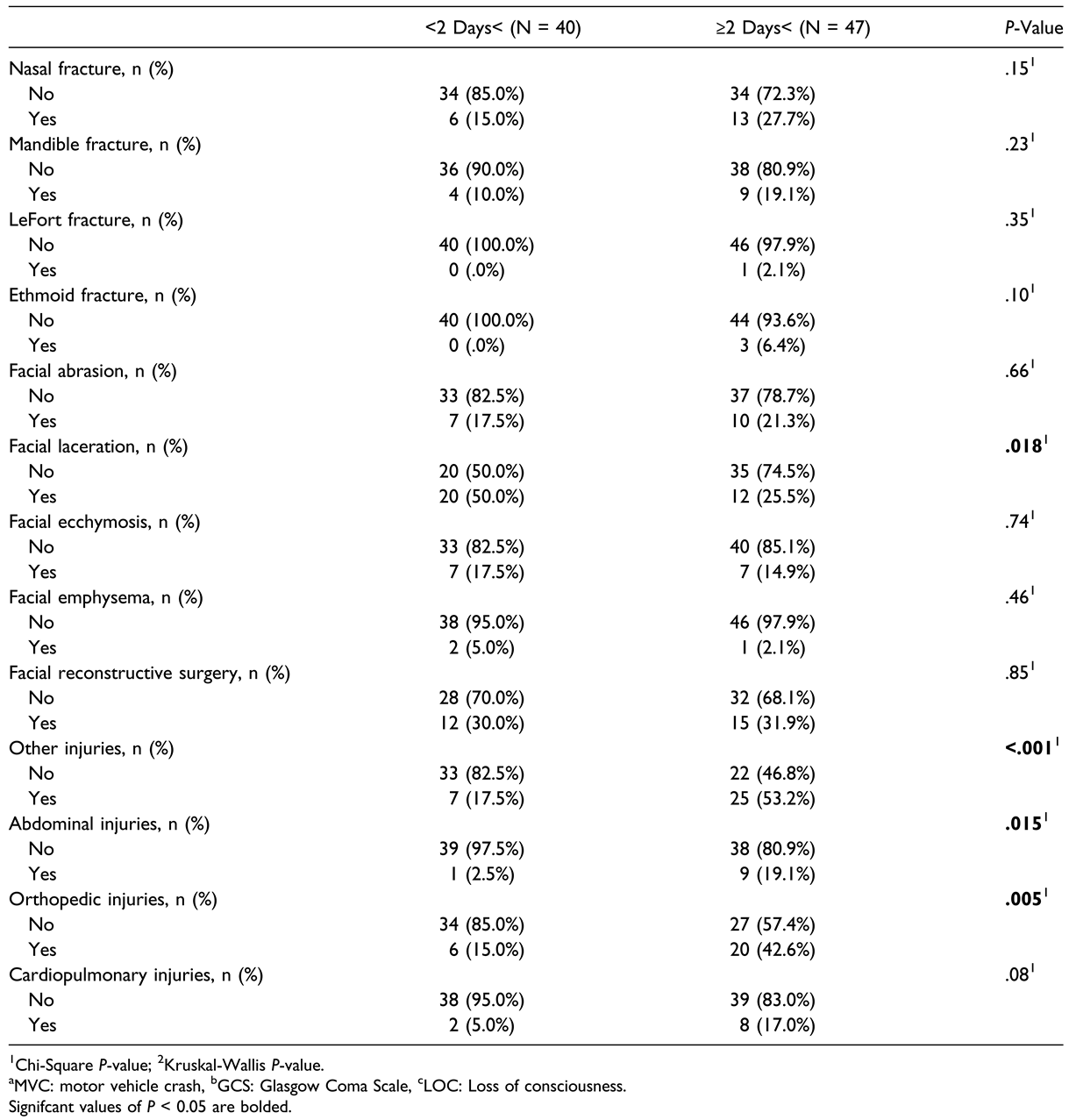

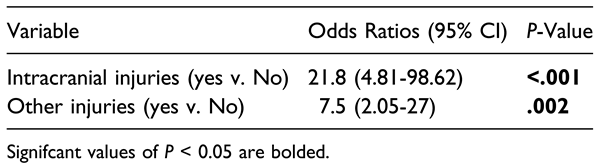

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Statement

References

- Anderson, C.; Kenda, L. What kinds of places attract and sustain amish populations? Rural Sociol. 2015, 80, 483–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Potts, L. The Amish health culture and culturally sensitive health services: an exhaustive narrative review. Soc Sci Med. 2020, 265, 113466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.E.; Brown, C.T.; Whitney, L.; Bonneville, K.; Perea, L.L. An overview of amish mortalities at a level I trauma center. Am Surg. 2022, 88, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, M.A.; Rzucidlo, S.; Shaffer, M.L.; Ceneviva, G.D.; Thomas, N.J. The impact of pediatric trauma in the Amish community. J Pediatr. 2006, 148, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitney, L.; Bonneville, K.; Morgan, M.; Perea, L.L. Mechanisms of injury among the amish population in central Pennsylvania. Am Surg. 2022, 88, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, J.E.; Licata, J.J.; Othman, S.; Shokri, T.; Zwillenberg, S. Comparison of maxillofacial trauma patterns in the urban versus suburban environment: a pilot study. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr. 2020, 13, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyer, S.M.; Hustey, V.R.; Rathbun, L.; et al. A look into the Amish culture: what should we learn? J Transcult Nurs. 2003, 14, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, J.A.; Bonalumi, N.M. Health care beliefs and practices among the Pennsylvania Amish. J Emerg Nurs. 1995, 21, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strotmeyer, S.; Koff, A.; Honeyman, J.N.; Gaines, B.A. Injuries among Amish children: opportunities for prevention. Inj Epidemiol. 2019, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Bustos, V.P.; Lee, B.T. Sources of facial injury across age groups: a nationwide overview using the national electronic injury surveillance system database. J Craniofac Surg. 2023, 34, 1927–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, C.; Ayoung-Chee, P.; Shinseki, M.; et al. Traumatic injury in the United States: in-patient epidemiology 2000-2011. Injury. 2016, 47, 1393–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Oleck, N.C.; Liu, F.C.; et al. Motor vehicle collision injuries: an analysis of facial fractures in the urban pediatric population. J Craniofac Surg. 2020, 31, 1910–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.U.; Rahat, S.; Khan, Z.A.; Shahid, L.; Banouri, S.S.; Muhammad, N. Etiology and pattern of maxillofacial trauma. PLoS One. 2022, 17, e0275515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvi, A.; Doherty, T.; Lewen, G. Facial fractures and concomitant injuries in trauma patients. Laryngoscope. 2003, 113, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohio Department of Transportation. Amish Safety; Ohio Department of Transportation: Columbus, OH, USA. Available online: https://www.transportation.ohio.gov/about-us/resources/amish-safety (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- Gorucu, S.; Murphy, D.J.; Kassab, C. Injury risks for on-road farm equipment and horse and buggy crashes in Pennsylvania: 2010-2013. Traffic Inj Prev. 2017, 18, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinner, D.H.; Paoletti, M.G.; Stinner, B.R. In search of traditional farm wisdom for a more sustainable agriculture: a study of Amish farming and society. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 1989, 27, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.A.; Scherzer, D.J.; Buckley, J.W.; Haley, K.J.; Shields, B.J. Pediatric farm-related injuries: a series of 96 hospitalized patients. Clin Pediatr. 2004, 43, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, J.M.; Jones, P.J.; Field, W.E.; Kraybill, D.B.; Scott, S.E. Farm-related injuries among Old Order Anabaptist children: developing a baseline from which to formulate and assess future prevention strategies. J Agromed. 2007, 12, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douthit, N.; Kiv, S.; Dwolatzky, T.; Biswas, S. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Publ Health. 2015, 129, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmlinger, I. Meeting the need for hearing screening in the amish community. Hear J. 2014, 67, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, E.K.; Gross, B.W.; Jammula, S.; et al. Preliminary results of a novel hay-hole fall prevention initiative. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018, 84, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrer, K.; Dundes, L. Sharing the load: Amish healthcare financing. Healthcare. 2016, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, G.E.R. Caring for the amish: what every anesthesiologist should know. Anesth Analg. 2017, 124, 1520–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allareddy, V.; Nalliah, R.P. Epidemiology of facial fracture injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011, 69, 2613–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, M.J.; Morris, C.K.; Kim, J.W.; Lad, S.P.; Arrigo, R.T.; Lad, E.M. Orbital fractures: national inpatient trends and complications. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013, 29, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, M.; Canner, J.K.; Hall, L.; Ahmad, M.; Srikumaran, D.; Woreta, F.A. Characteristics of orbital floor fractures in the United States from 2006 to 2017. Ophthalmology. 2021, 128, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

|

© 2024 by the author. The Author(s) 2024.

Share and Cite

Sciscent, B.Y.; Eberly, H.W.; King, T.S.; Bavier, R.; Lighthall, J.G. Evaluating Facial Trauma in the Amish: A Study of a Unique Patient Population. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2024, 17, 60. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875241259887

Sciscent BY, Eberly HW, King TS, Bavier R, Lighthall JG. Evaluating Facial Trauma in the Amish: A Study of a Unique Patient Population. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2024; 17(4):60. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875241259887

Chicago/Turabian StyleSciscent, Bao Y., Hanel W. Eberly, Tonya S. King, Richard Bavier, and Jessyka G. Lighthall. 2024. "Evaluating Facial Trauma in the Amish: A Study of a Unique Patient Population" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 17, no. 4: 60. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875241259887

APA StyleSciscent, B. Y., Eberly, H. W., King, T. S., Bavier, R., & Lighthall, J. G. (2024). Evaluating Facial Trauma in the Amish: A Study of a Unique Patient Population. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 17(4), 60. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875241259887