Introduction

Modified approaches for airway establishment are frequently necessary for complex fractures encompassing the upper, middle, and lower thirds of the face simultaneously. Addressing the orbital, oral, and nasal cavity volumes, alongside restoring the proper three-dimensional relationships within the facial frame are the foremost objectives of facial reconstruction. Oral and maxillofacial surgeons have three key concerns while treating complex trauma: maintaining adequate tooth occlusion, supporting facial soft tissues, and nasal projection and patency.[

1]

Classical endotracheal intubation might not always be feasible in cases of craniofacial trauma, particularly if the nasal pyramid or the anterior skull base has been impacted or in cases where intraoperative control of occlusion is necessary. In cases of multiple facial fractures in dentate patients where malocclusion needs to be corrected intraoperatively, orotracheal intubation precludes maxillomandibular fixation (MMF).[

2,

3] In addition to being unsuitable in situations of skull base fractures, nasotracheal intubation hinders the treatment of nasal fracture repair. Tracheostomy is one of the common methods recommended for patients who require extended intubation to protect the vocal cords from harm and also taking into consideration those with neck trauma who have restricted airway throughout the recuperation period.[

4] Similar to all surgical operations, risk and morbidity rate ranges from 14% to 45%. Tracheostomy can lead to several possible negative consequences.[

2,

3]

Complex fractures like panfacial fractures affect the mandible, maxilla, NOE region, zygomaticomaxillary complex, and frontal bones simultaneously. Managing facial trauma is an ongoing challenge for both Maxillofacial surgeons and Anesthetists. Appropriate intubation procedures must be used to achieve both a satisfactory functional outcome and facial aesthetic contour.

Effectively managing airways during the intraoperative phase of panfacial trauma is an absolute necessity, and requires a high level of skill and expertise.[

5] The primary factor taken into account when selecting an intubation technique is the estimated duration of recovery necessitating airway management. An alternative to the traditional techniques is submental intubation.[

3]

The purpose of this study was to determine whether SEI (submental endotracheal intubation) could be a practical substitute for traditional approaches when it comes to managing anesthesia in patients with craniomaxillofacial trauma, particularly in cases where only short-term postoperative airway control had been anticipated.[

1] This study was conducted to gain a better understanding of the frequency range, purposes, and outcomes of submental intubation in patients with craniofacial trauma. It mainly focused on perioperative and postoperative complications encountered after submental intubation and deriving ways for avoiding and managing the same.

Results

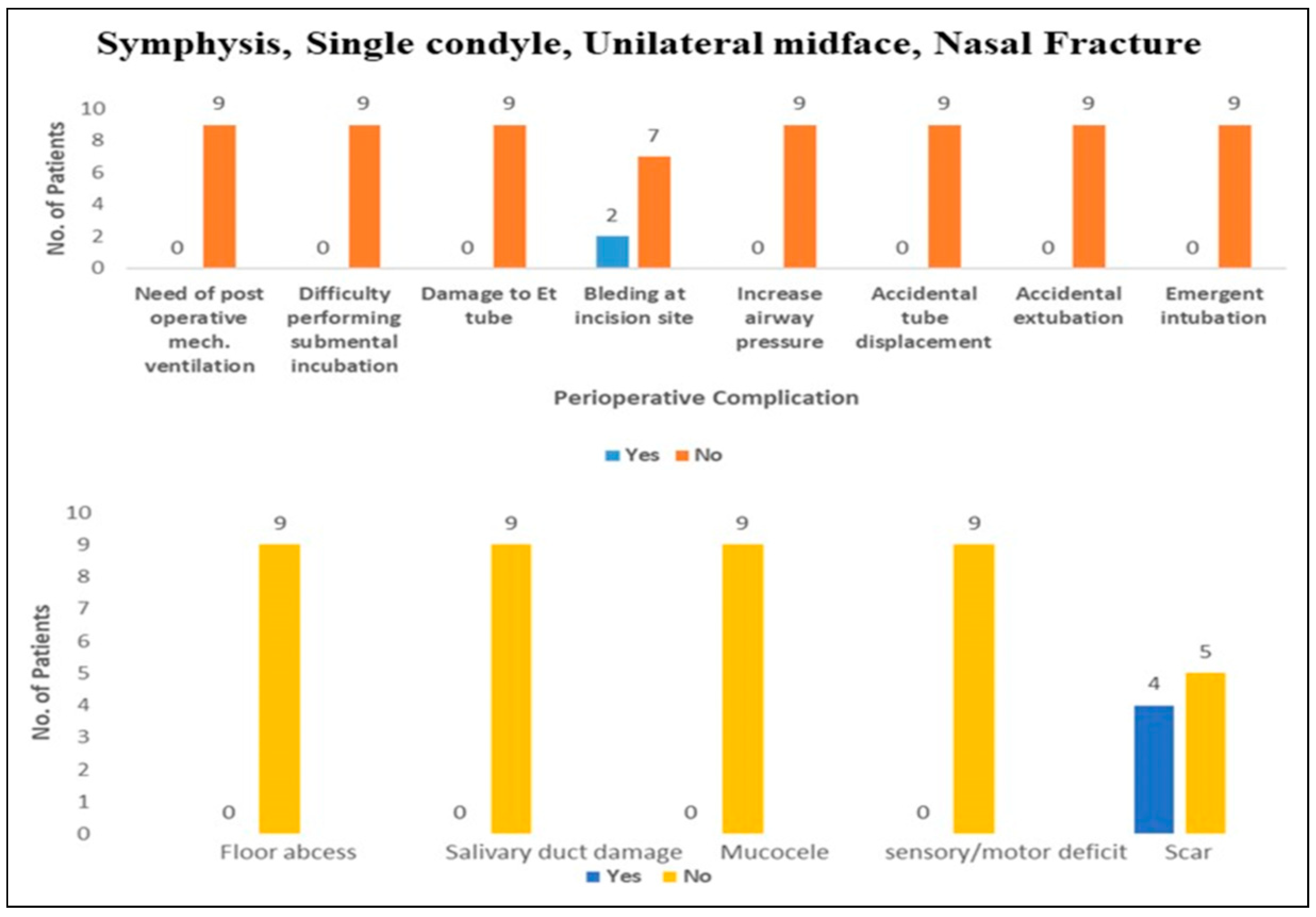

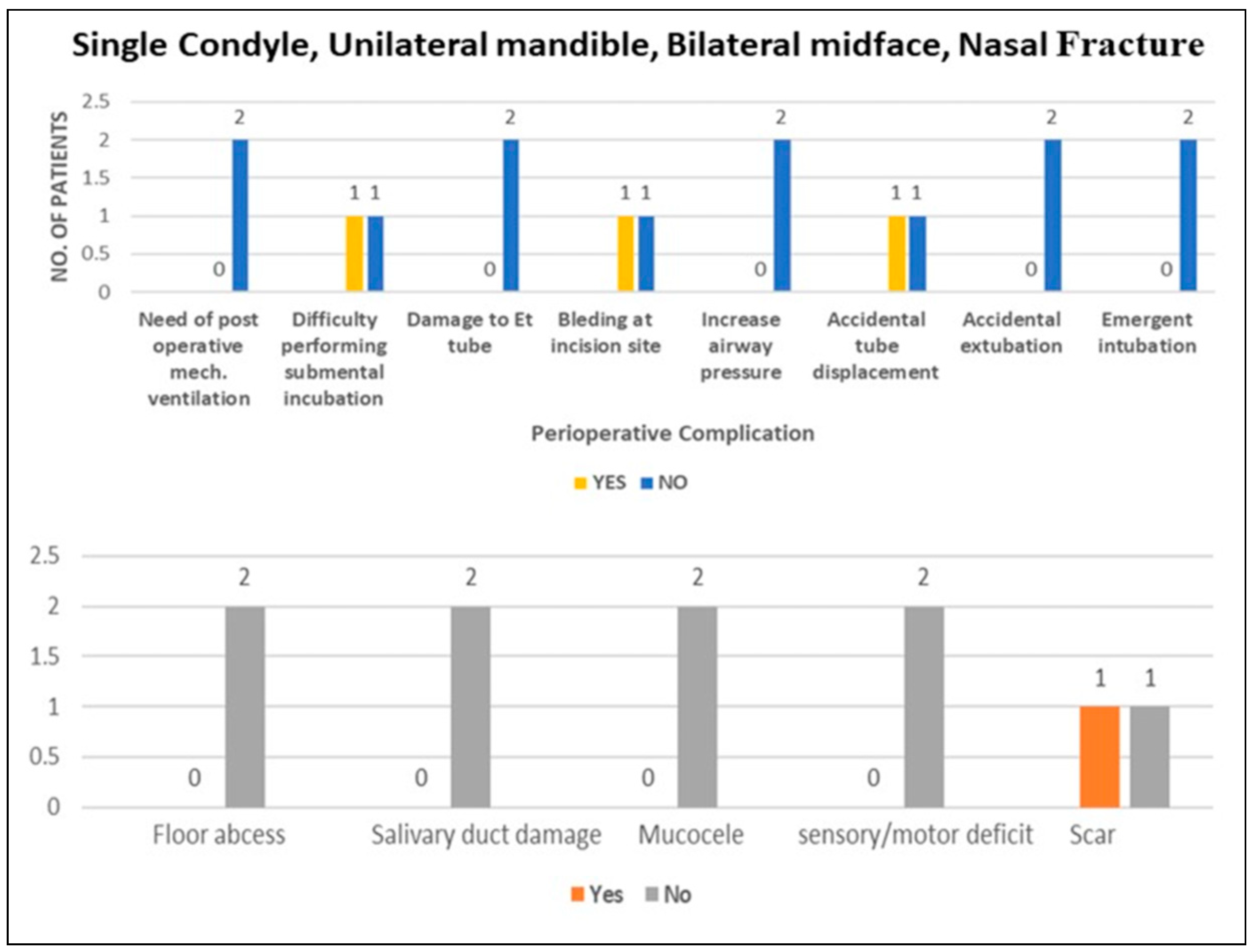

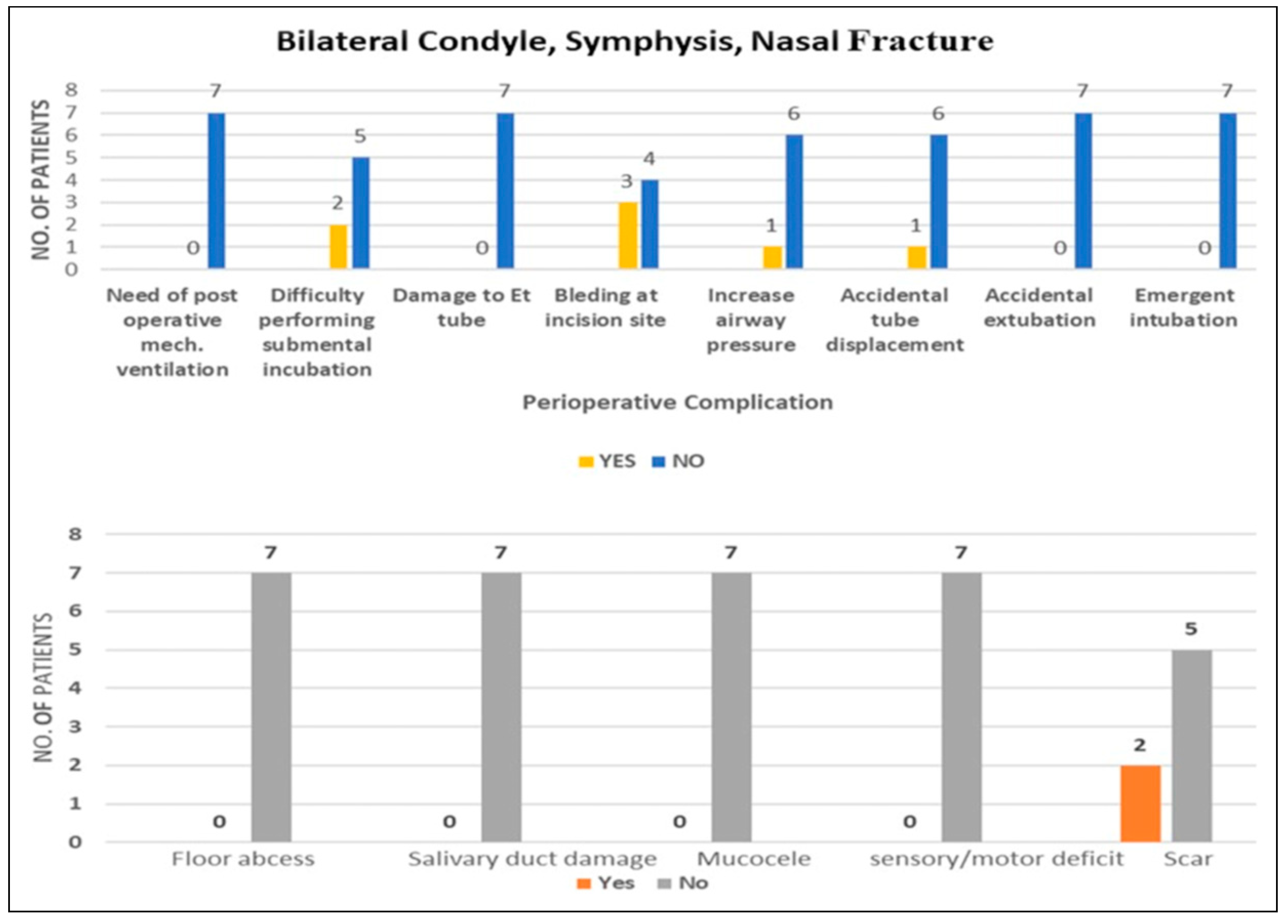

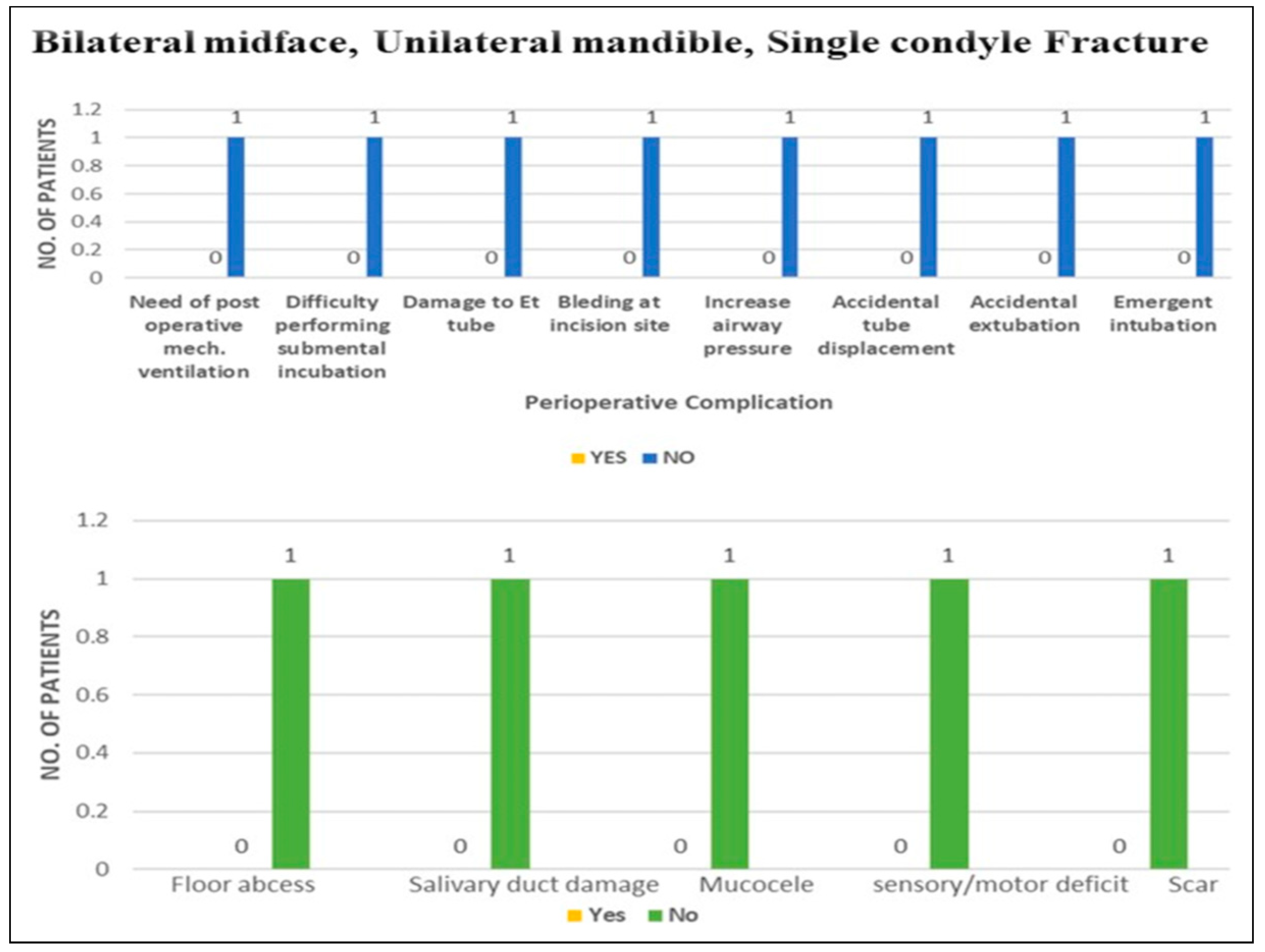

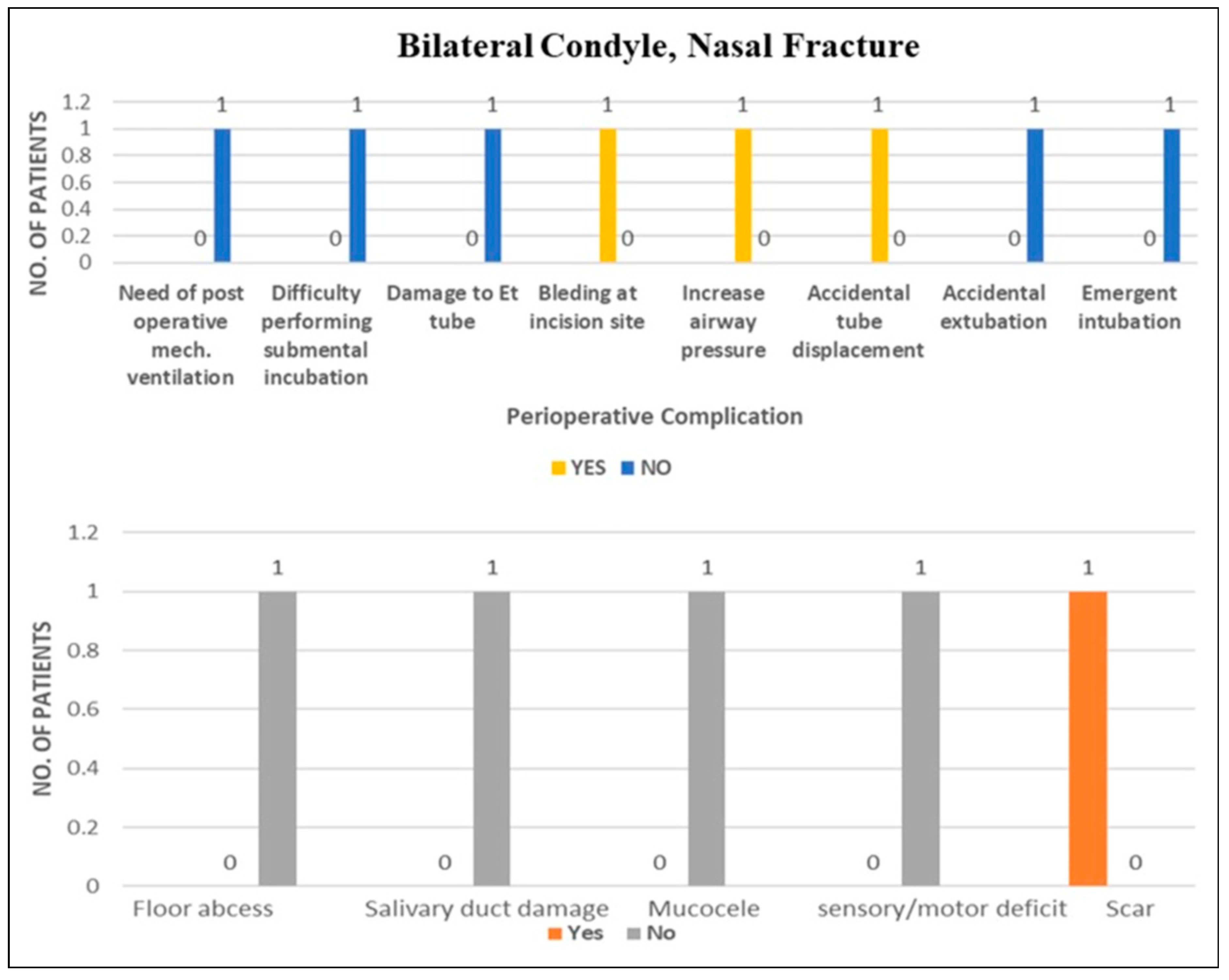

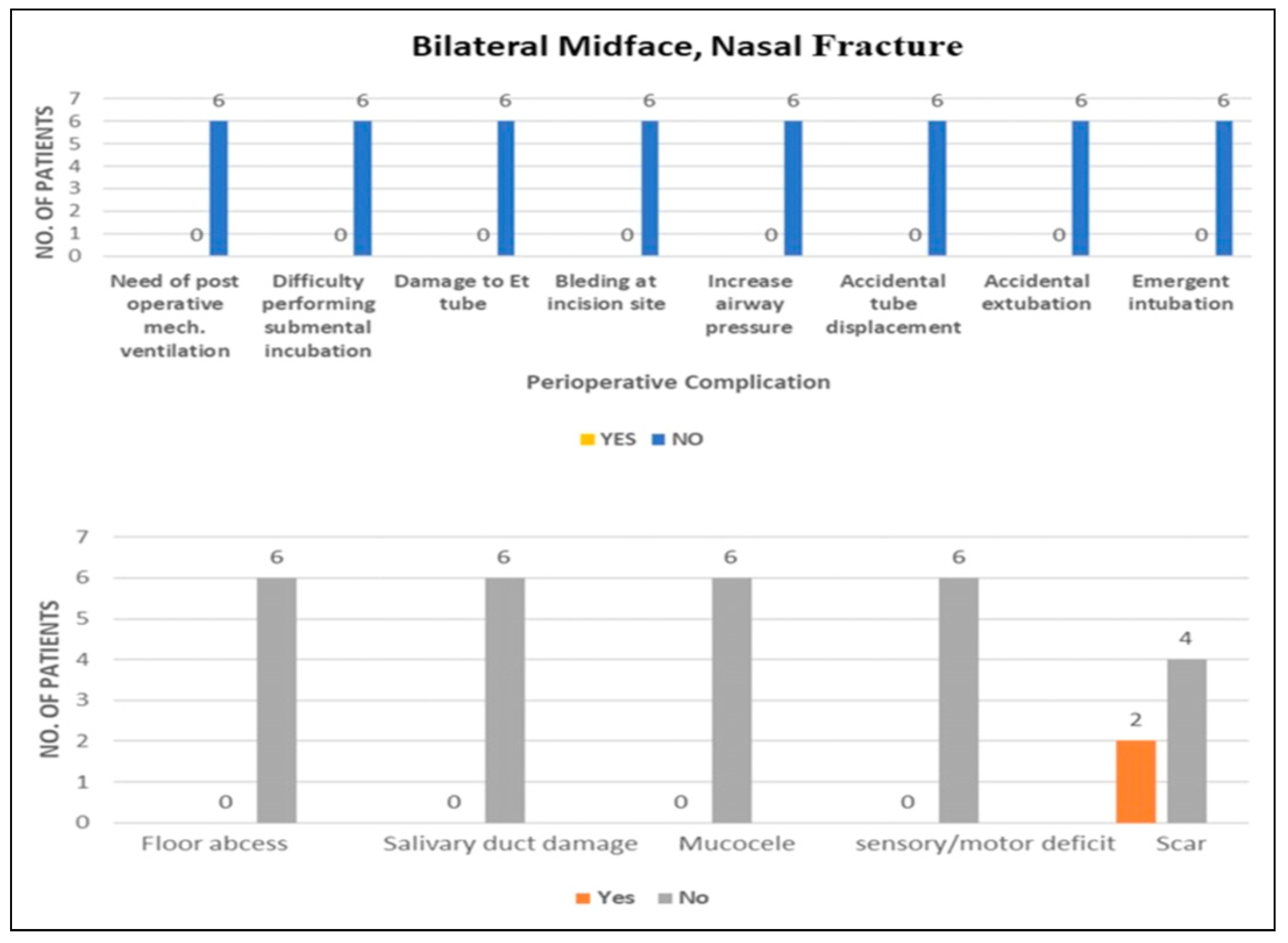

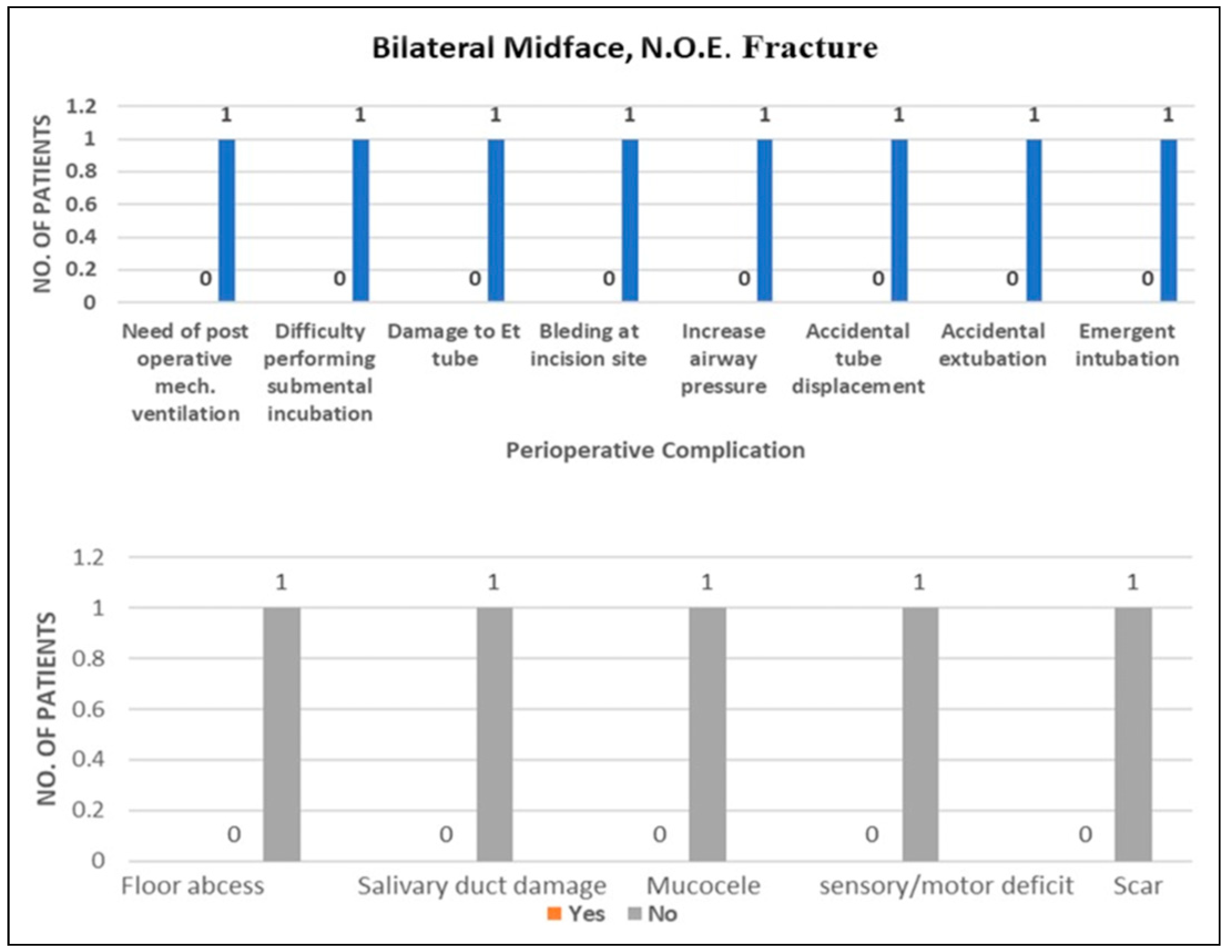

We carried a retrospective study for 9 years from -January 2015 to August 2023. Seventy -Two patients were included in our study all with craniomaxillofacial trauma. Diagnosis included fracture of unilateral or bilateral condyle of mandible combined with symphysis or body fracture, with unilateral or bilateral midface and NOE or nasal fracture. Diagnosis other than trauma were not included. Because of their nasal bone or nasal-orbito-ethmoidal complex fractures, none of these patients could benefit from using a nasaltracheal airway. Data obtained was statistically analyzed for perioperative and postoperative complication for following diagnosis Symphysis, single condyle, unilateral midface, Nasal [

Graph 1], Symphysis, bilateral condyle, unilateral midface, N.O.E [

Graph 2], Single condyle, unilateral mandible, unilateral midface, nasal [

Graph 3], Single condyle, unilateral mandible, bilateral midface, nasal [

Graph 4], Bilateral condyle, symphysis, nasal [

Graph 5], Bilateral condyle, unilateral midface, N.O.E. [

Graph 6],Bilateral midface, unilateral mandible, single condyle [

Graph 7], Bilateral condyle, nasal [

Graph 8], Bilateral midface, nasal [

Graph 9], Bilateral midface, N.O.E.[

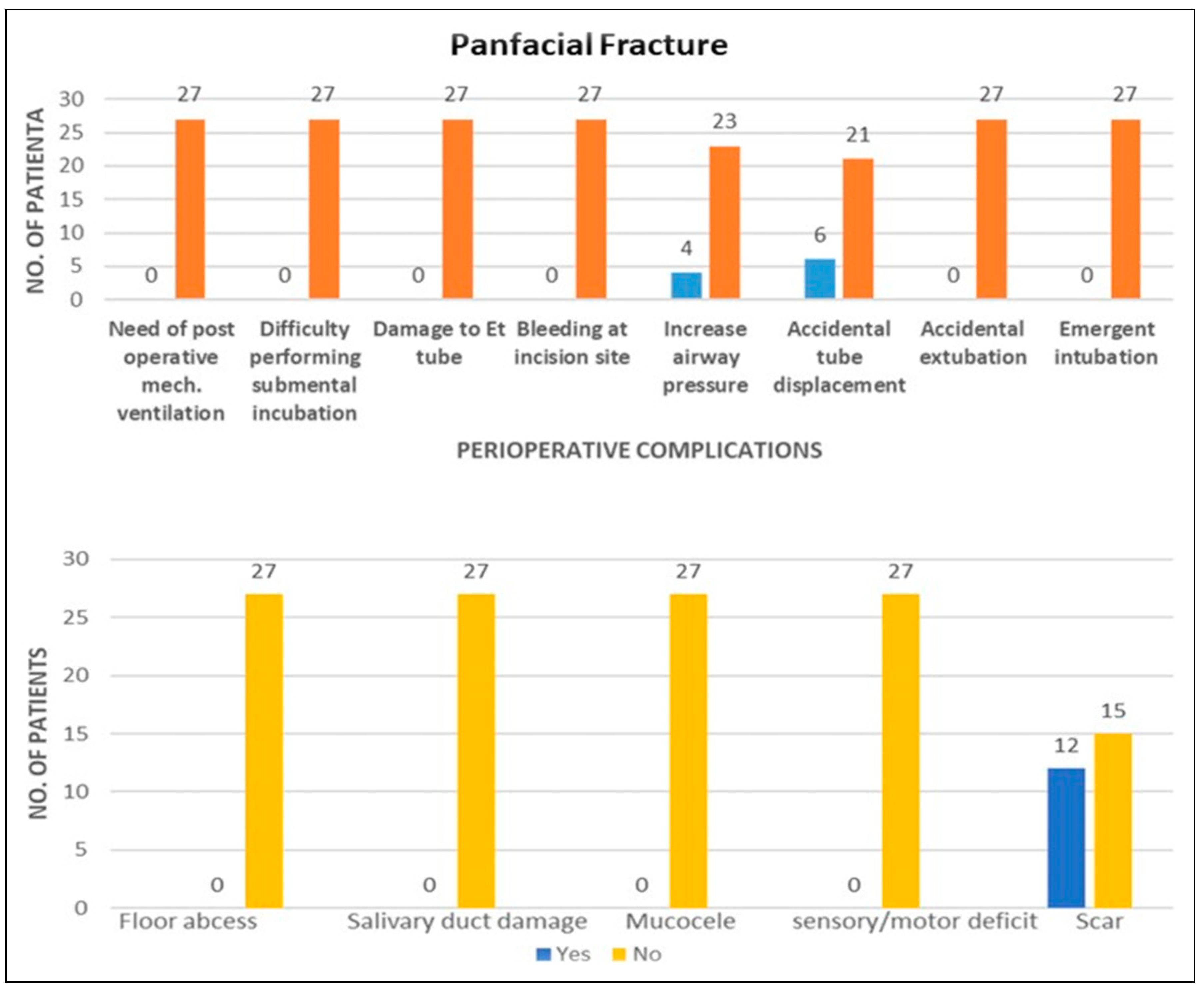

Graph 10], Panfacial fractures[

Graph 11].

Out of 72 patients, difficulty during intubation was faced in 6 patients and 9 patients showed accidental tube displacement out of which 6 cases were of panfacial fractures. 8 patients showed increased airway pressure intraoperatively with use of multiple methods for managing it. In our study only 12% tube displacement, 11.1% high air pressure, 12% bleeding at site of intubation complication were seen. Incidence of post operative complications like floor abscess, injury to salivary gland or duct, mucocele, sensory and motor deficits were not encountered. Scar was seen in 17 cases.

Discussion

Traditionally, the options for administering anesthesia and managing the airway were oral, nasal, or tracheostomy.[

6] In maxillofacial injuries, each airway management strategy has specific indications, benefits, and drawbacks. The decision should always be based on the availability of suitable instruments, the experience of the participating surgeons and anesthetists, and frequently the patient’s agreement.[

5,

7] Beyond craniomaxillofacial trauma, orthognathic surgery and elective craniomaxillofacial procedures requiring reference to dental occlusion are among the possible grounds for submental intubation.[

5,

6]

In 1986, Hernandez Altemir proposed a Median submental (retro-genial)[

5] or Iranian technique [

1] for intubation.[

8] There have been several recorded modifications to this approach since then. The anterior submandibular approach was described by Stoll et al. in 1994.[

9] This modification is not only safer but also more advantageous.[

5] In 1996, Green and Moore published a procedure that involved the usual oral intubation of a patient using two tubes. This method can be applied on

tubes only when the universal connector is available.[

4,

10] A modified technique was described by MacInnis et al. (1999), in which an intraoral incision was placed posterior to the submandibular duct papilla. This procedure carries a risk of edema development and sublingual hematoma, which could be dangerous.[

1]

An intraoral incision placed anterior to the submandibular duct papillae was employed during intubation by Mahmood and Lello (2002). This technique reduces the risk of lingual nerve and duct papillae injury, preventing sublingual hematoma and edema.[

11,

12] In 2000, Montero and Altemir reviewed submental intubation with a laryngeal mask airway used in patients who have unstable cervical fractures or laryngotracheal trauma.[

13] In 2006, Zoltán Nyárády, Ferenc Sári, and colleagues employed the 222 rule to guide the passage of tube to improve the safety of submental incision.[

14] Various other modifications of SEI are the Ring-Adair-Elwyn tube method,[

15] the novel method using Seldinger’s technique,[

16] and Griggs forceps modification.[

17] In our study, the anterior submandibular technique of submental intubation of Stoll et al [

9] was carried out on all 72 patients. The primary benefit of this method over the median submental approach is that the tube only goes through mylohyoid muscles (trans-mylohyoid)[

17] Considering this shorter route avoids impacting the geniohyoid and genioglossus muscles, thus reducing the risks and complications associated with intubation.[

5] Thus, we can infer that the anterior-submandibular or submental-submandibular approach is the most preferred and safest technique among all modifications.

It has been reported by Willian Caetano Rodrigues et al. that there are no problems or complications, no incidents of endotracheal tube displacement and perioperative hemorrhage during SEI.[

7] In our study on 72 patients, difficult intubation was faced for 6 patients and 9 patients showed accidental tube displacement. Out of these 9 patients with tube displacement, 6 patients had a diagnosis of panfacial fractures. Displacement of the tube can cause accidental extubation, endobronchial intubation, vocal cord injury, laryngospasms, and aspiration pneumonia. We did not encounter any case of accidental extubation.

According to Jin-Tae Kim et al. (2009), head rotation in the direction of ET fixation may result in a partial withdrawal of the tube tip from the carnia, and head rotation in the opposite direction may induce an unanticipated displacement of the tube. In children (1-9 years age group), head rotation in the same or opposite direction of ET fixation can cause withdrawal of the ET tube.[

18]

Full extension, shorter neck, and large BMI are major risk factors that can cause tube displacement. Surgical manipulation can also cause complete dislodgement.

Unnoticed extubation can cause inadequate ventilation sequelae of hypoxemia, hypotension, brain damage and cardiac arrest. In a study by Chandu et al., they found that two patients out of 44 undergoing orthognathic surgery experienced unexpected extubation.[

19]

As we can see in our study also, the incidence of accidental tube displacement was rare (only 9 patients out of 72) and of accidental extubation was none, we can conclude that submental intubation can be safely and effectively performed for managing patients of multiple craniomaxillofacial fractures.

According to a 2017 study by Caetano Rodrigues et al, there was no instance of compromised airway or arterial desaturation throughout the perioperative period under submental intubation.[

7] 8 patients showed increased airway pressure perioperatively in our study. High airway pressure can be due to machine associated causes like kinking, pooling of condensed water vapour, increased resistance of wet filters, and obstruction of ET tube. Man-associated causes may be bronchospasm, Pulmonary compliance, edema, consolidation, pleural effusion or pneumothorax which might be preexisting or develop intraoperatively. The normal range for PEEP is 15-25 cm H2O. Pressure exceeding 30 cm H20 is considered high. Only Rapid change in positive end-expiratory pressure from 25 cm H2O to suddenly 30-45 cm H2O is of concern. The causes of pressure changes must be assessed. Necessary adjustments in the circuit, ET tube positioning, obstruction removal by suctioning, and corticosteroid loading dose may be implemented. Airway emergency can be managed temporarily by Bag-valve-mask or supraglottic device ventilation. Rapid desaturation gives no time to draw up propofol, muscle relaxant, or introduce a video laryngoscope.

While managing this, FiO2 to be delivered is shifted to 100% on VC (volume control) or PC (pressure control). The supraglottic airway of proper depth can provide an adequate seal. Rapid sequence induction (RSI) helps us to take control of the airway faster. Bag mask (BVM) ventilation is generally not advised during rapid sequence induction because of the risk of aspirating the lungs, insufflating the stomach, and causing reflux of the stomach contents. If BVM or RSI methods fail, surgery needs to be terminated, and percutaneous tracheostomy or cricothyrotomy needs to be performed.[

2] Incidence of such an airway emergency was not found in our study. Also, no patient in our study required emergent intubation or percutaneous tracheostomy.

Nicolas Lazaridis et al. suggest that the duration of the procedure is the primary consideration when choosing submental intubation. When the procedure is over, the tube is typically put back in the mouth and left there until extubation is judged safe.[

5] None of the 45 patients in the retrospective analysis by J. E. O. Connell and G. J. Kearns (2013) needed ventilator support or long-term airway protection.[

4] According to Rodrigues et al, patients who had bilateral mandibular fractures required more post-operative mechanical ventilation due to more soft tissue manipulation and longer surgical times, which exacerbated submandibular edema.[

7] No patient in our study required post-operative prolonged mechanical ventilation.

A retrospective study was conducted from 2014-2018 among 498 maxillofacial trauma patients by Ravi Mishra et al. In this investigation, 1 out of 23 patients experienced a pilot balloon perforation during tube manipulation, from the intraoral to the extraoral submental plane, which was effectively managed.[

20] In 2023, Stefania Troise et al, studied a novel method of pilot balloon protection in submental intubation on 21 patients, in which an inflating line was passed behind the last tooth and removed extra-orally not interfering with MMF, proposed to reduce the incidence of rupture, damage, and early extubation.[

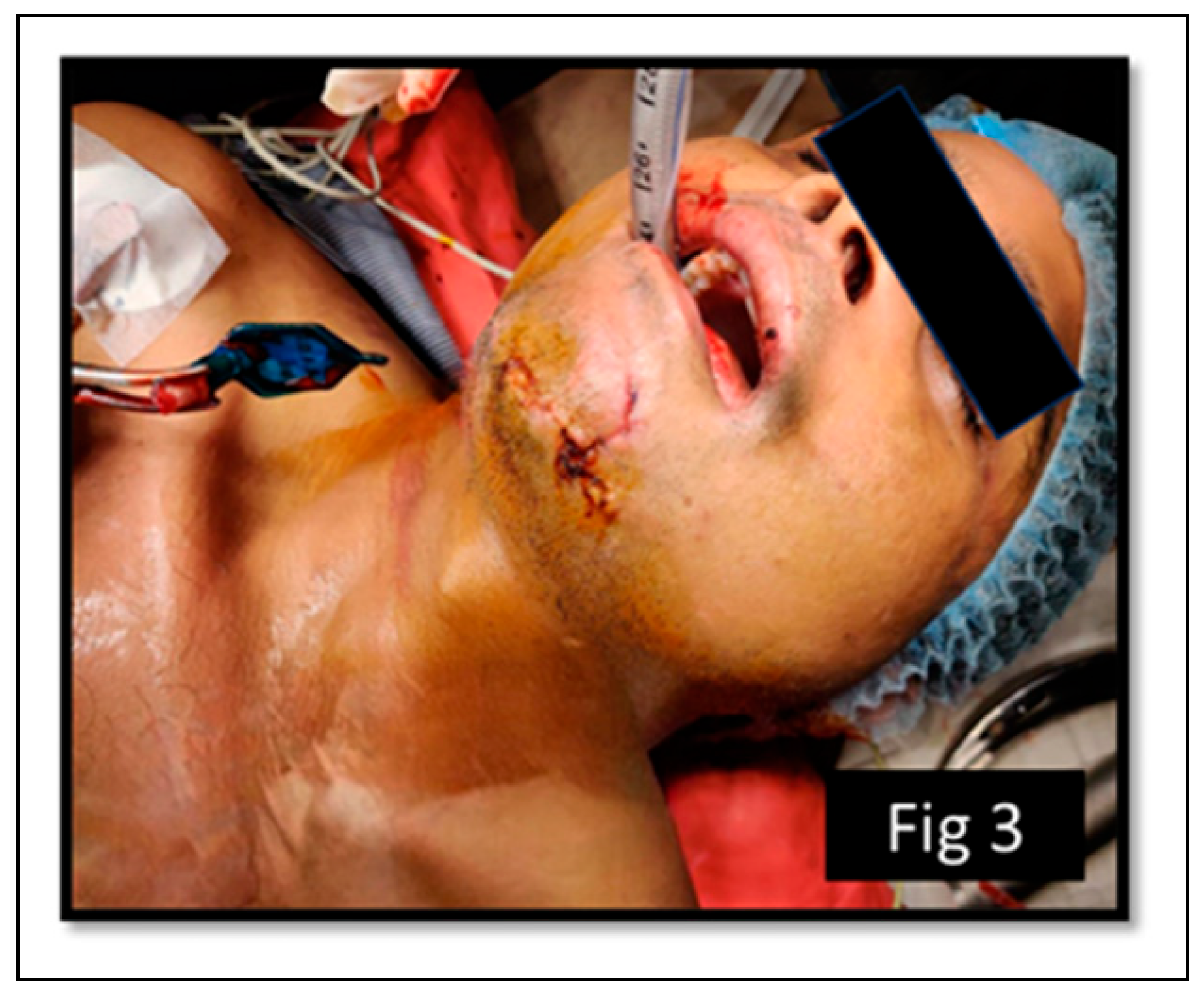

21] While analyzing data in our study we came out with a novel modification method of safe extubation for which we have got a literary copyright from the Government of India (L-139214/2023). In this modification, we did not reverse the pilot balloon and cuff inflating line through the tunnel. After a slight reversal of ET orally, the tracheal balloon is deflated, sutures are taken for closure of the paramedian incision and then the pilot balloon is cut extra-orally which makes the extubation very easy and safe [

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3]. Damage to the inflating line of the pilot balloon can cause - Low cuff pressure causing an increased vocal space-increasing chances of gastric content aspiration in lungs, difficulty in maintaining tidal volume pressure of about 600-700 mL, and need for prolonged mechanical ventilation or continued intubation for 24 hours. Our novel method prevents damage or breakage of the inflating line of the pilot balloon, thus increasing the efficacy of intubation.

Various retrospective study from the past 36 years was reviewed. Amin et al, in 2002 in their study of 12 participants noticed endo-bronchial intubation and bleeding in 1 case and inadvertent extubation in 1 case.[

22] In a study, carried out on 107 participants in 2006, Taglialatela et al noted 11 cases of superficial wound infection, 8 cases of oro-cutaneous fistula, which resolved in 10 days by conservative management, and damage to ETT apparatus in 6 cases.[

22] In 2010, Gadre and Waknis studied data from 400 participants and noted 2 cases of Oro cutaneous fistula, 1 case of ETT damage, and keloid formation in 2 participants.[

23] Kerry William et al in their review of literature from 2012-2022, recorded 2 % of premature extubation,10% of endotracheal tube damage, 23 % of infection, 10 % of fistula formation, and 1 % of lingual nerve damage and mucocele formation.[

24]

Coming to post-operative complications, based on a study of a modified technique of submental intubation on 8 patients in 2006, Zoltán Nyárády et al experienced no bleeding at the site of intubation in any case.[

1] In our study bleeding at the submental incision site was seen among 9 patients. This bleeding was not significant, did not affect surgical procedure, and needed no intervention of any form. In Altemir’s technical note of 1986, he listed some of the drawbacks of submental intubation, including the potential for infection of the oral cavity floor, the possibility of submental fistulae and abnormal scarring if the procedure is excessively stretched out, and harm to significant structures of floor of mouth.[

8] The potential drawback of submental intubation, according to Christophe Meyer et al, is scar formation. Patients have always well tolerated this scar, as it hides below the inferior border and is far less noticeable.[

7,

14] Risk of post-operative salivary fistula has been reported in the literature in cases of prolonged ventilation by Gordon and Tolstunov and Labbe et al.[

8] According to Stranc – Skoracki[

25] and Tagliatela et al,[

26] mucocele has been reported as a complication of submental intubation. The track could be bluntly dissected to prevent the formation of mucocele.[

5] Our study found no instances of floor abscesses, salivary gland or duct injuries, mucocele, or motor and sensory deficits. We encountered 23.6% of scar which was small, masked, and quite acceptable. Scar evaluation should be followed for up to 12-18 months to comment on its nature, depending on which surgical modalities for scar revision can be executed according to the need of the patient.