Management of Le Fort I Fractures

Abstract

Introduction

Materials & Methods

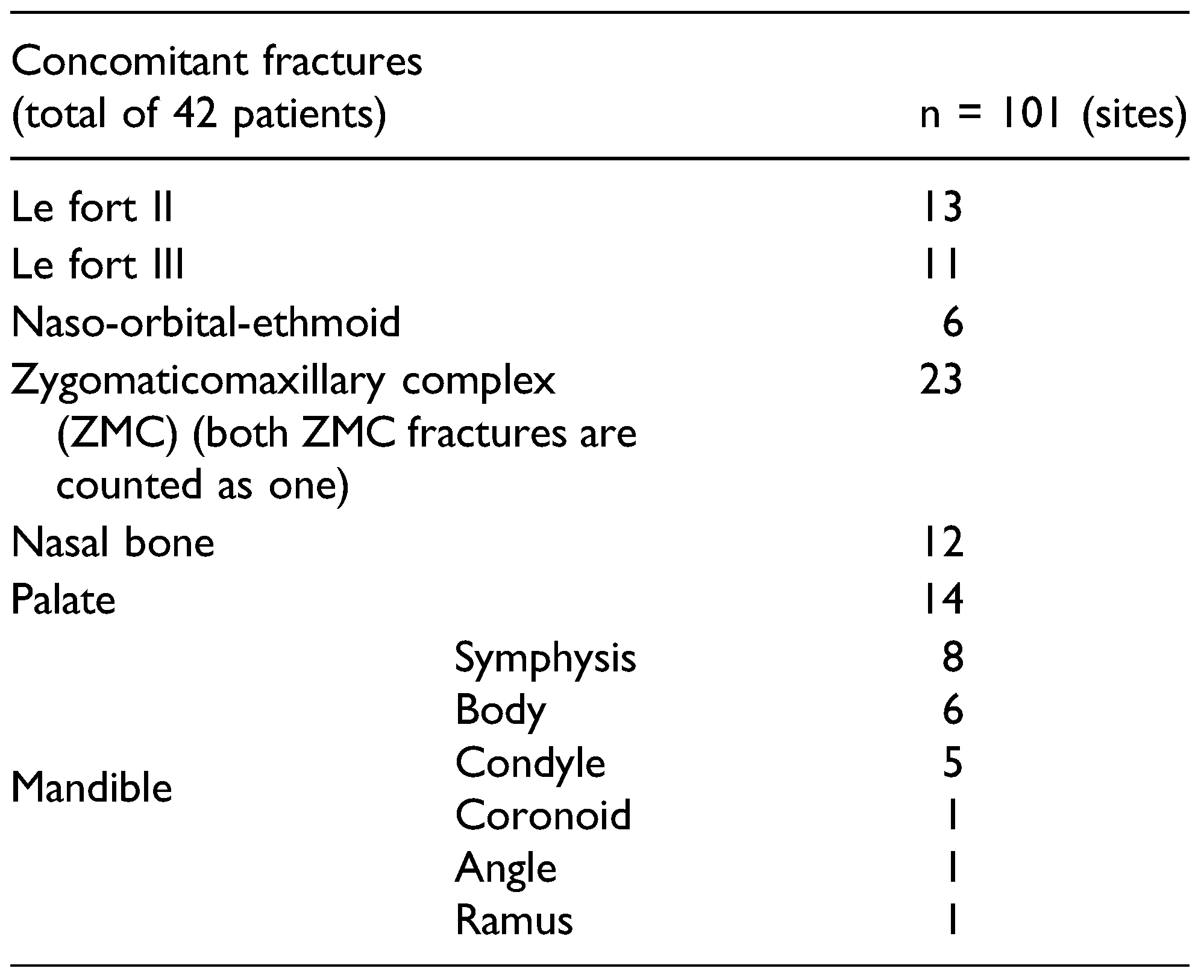

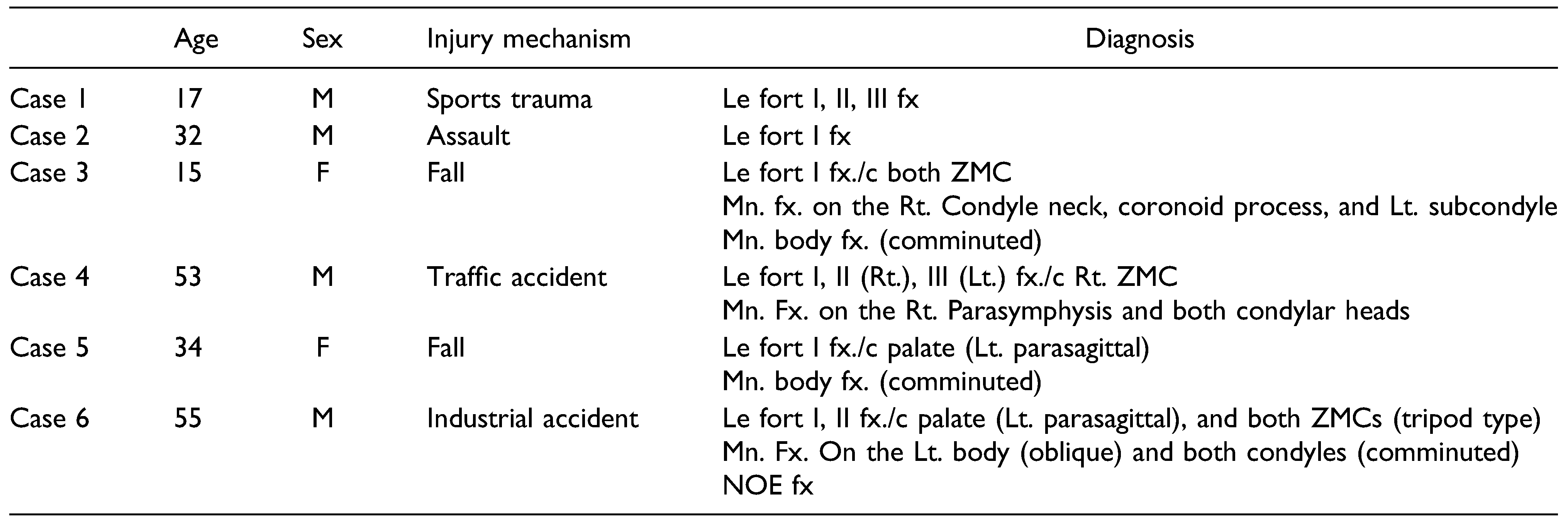

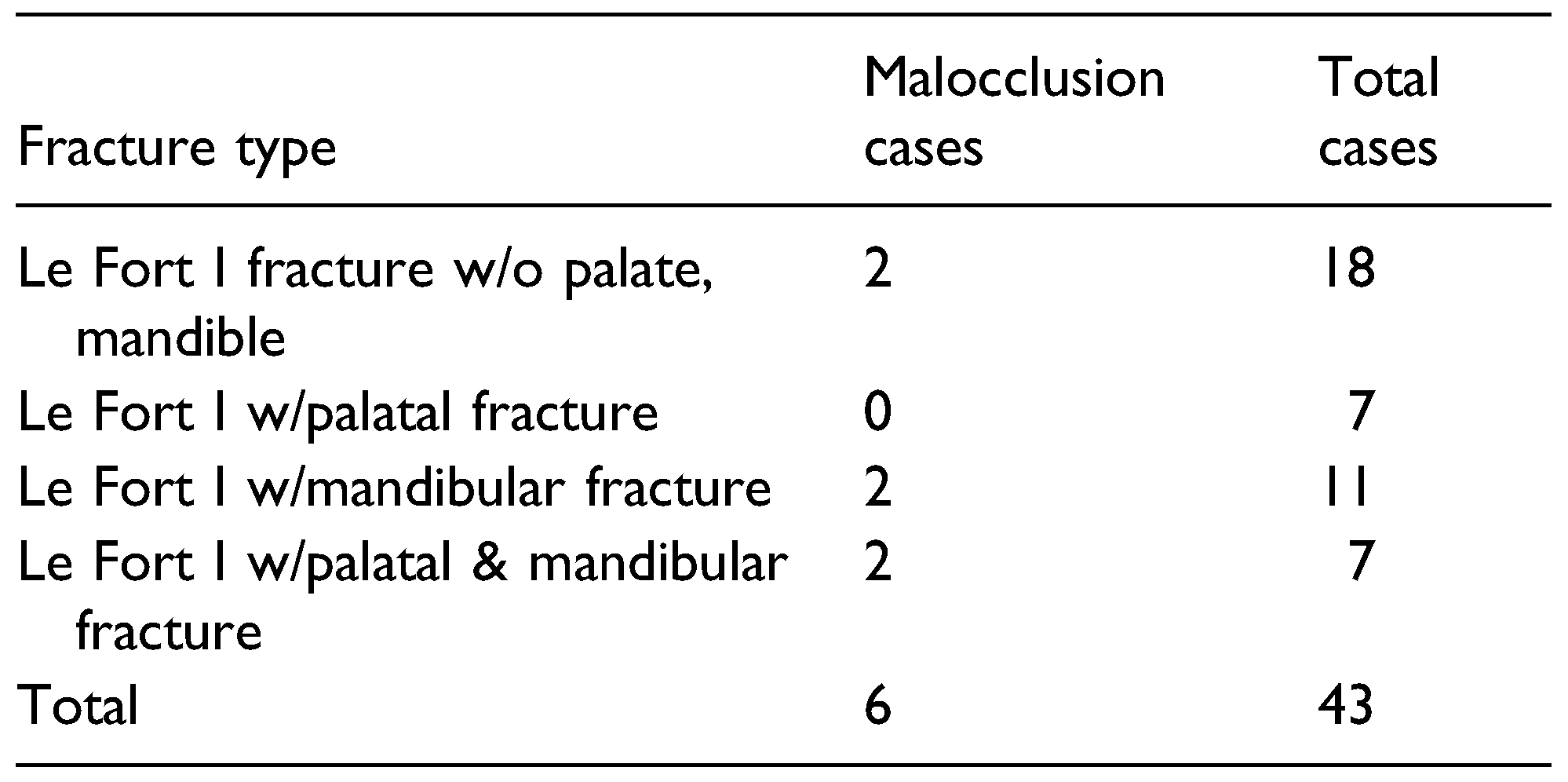

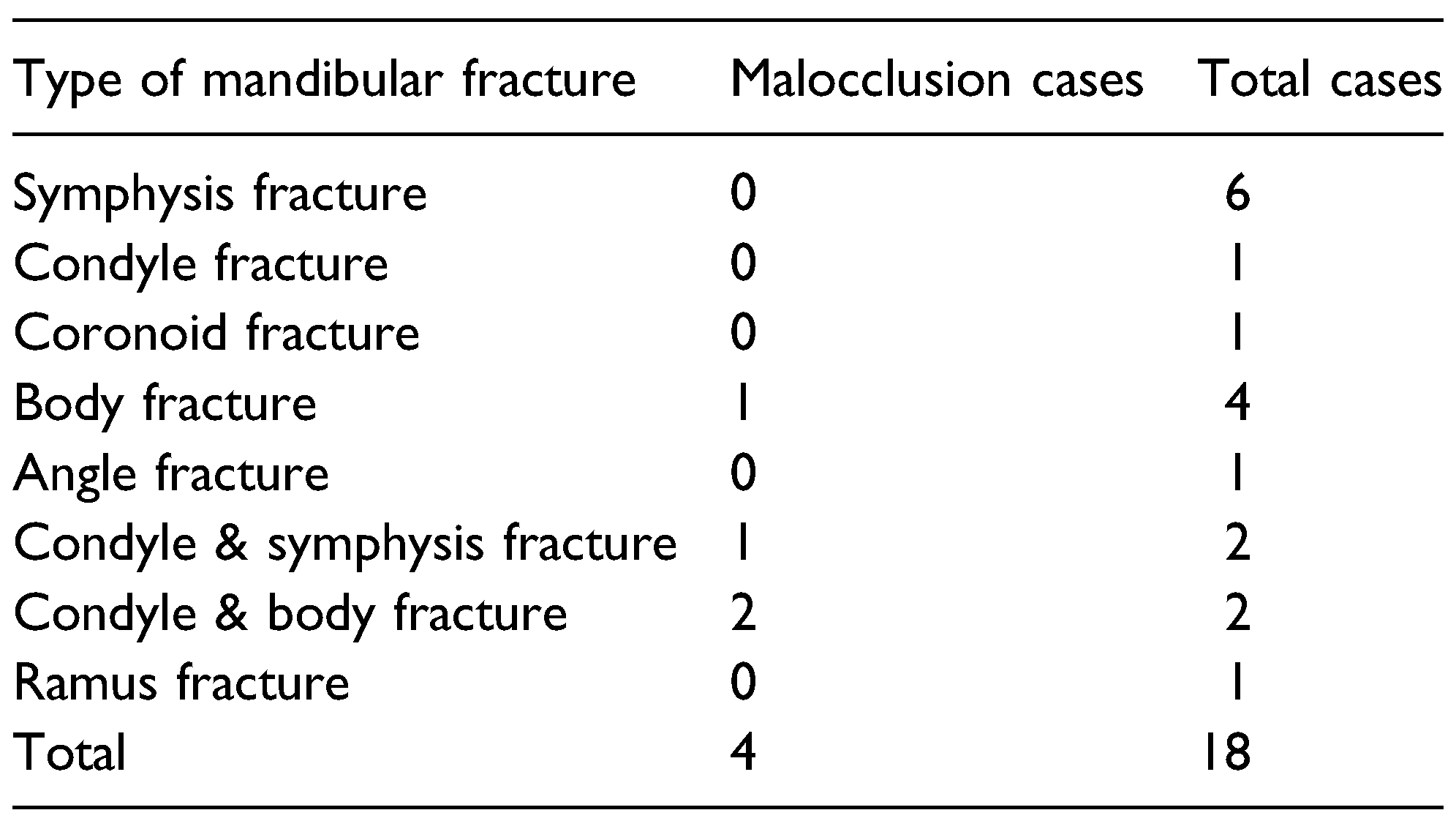

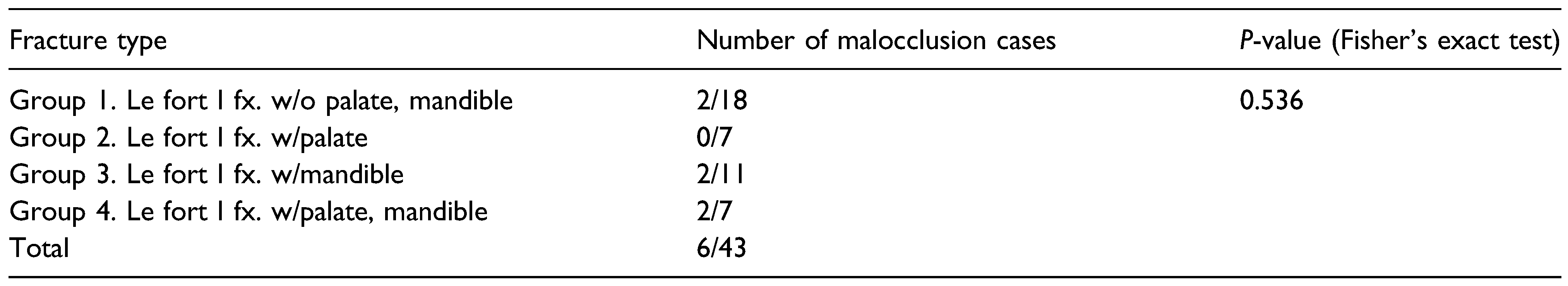

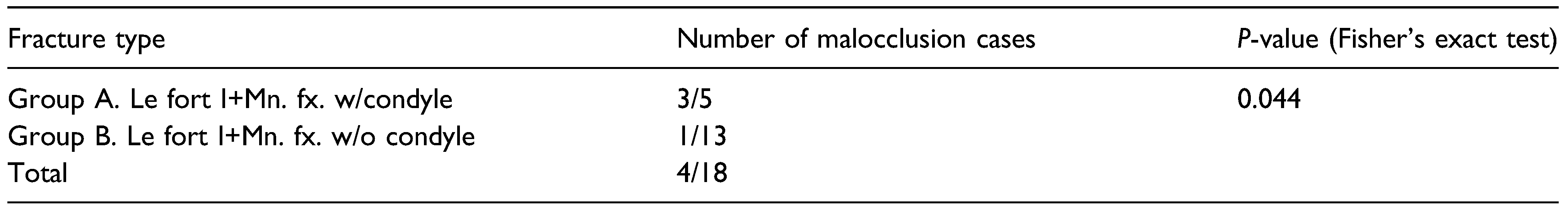

Results

Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roumeliotis, G.; Ahluwalia, R.; Jenkyn, T.; Yazdani, A. The Le Fort system revisited: trauma velocity predicts the path of Le Fort I fractures through the lateral buttress. Plast Surg. 2015, 23, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, E.; Obeid, G.; Banks, P. The irreducible middle third fracture, a problem in management. Br. J. Oral Surg. 1983, 21, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steidler, N.; Cook, R.; Reade, P. Residual complications in patients with major middle third facial fractures. Int. J. Oral Surg. 1980, 9, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scolozzi, P.; Imholz, B. Completion of nonreducible Le Fort fractures by Le Fort I osteotomy: sometimes an inevitable choice to avoid postoperative malocclusion. J Craniofac Surg. 2015, 26, e59–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, Z. Why should we start from mandibular fractures in the treatment of panfacial fractures? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012, 70, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, B.L.; Manson, P.N. Panfacial fractures: organization of treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 1989, 16, 105–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenig, B.L. Management of panfacial fractures. Otolaryngol Clin. 1991, 24, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, P.N.; Clark, N.; Robertson, B.; et al. Subunit principles in midface fractures: the importance of sagittal buttresses, soft- tissue re-ductions, and sequencing treatment of segmental fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999, 103, 1287–1306 quiz 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tullio, A.; Sesenna, E. Role of surgical reduction of condylar fractures in the management of panfacial fractures. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2000, 38, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, W.; Horswell, B.B. Panfacial fractures: an approach to management. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin. 2013, 25, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ellis, E. , 3rd. Panfacial fractures: analysis of 33 cases treated late. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007, 65, 2459–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardt, N.; Kuttenberger, J. Craniofacial Trauma: Diagnosis and Management; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 205–238. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, S.T.; Snyder, B.J.; Moore, M.H.; David, D.J. Outcome measurement of the treatment of maxillary fractures: a prospective analysis of 100 consecutive cases. Br J Plast Surg. 1999, 52, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, G.R.; Islam, S. The difficult Le Fort I osteotomy and downfracture: a review with consideration given to an atypical maxillary morphology. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2008, 61, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, J.J.; Manson, P.N.; Mirvis, S.E.; Dunham, M.; Crawley, W. Le Fort Fractures Without Mobility. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1990, 85, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2024 by the author. The Author(s) 2024.

Share and Cite

Cho, J.-y.; Ryu, J. Management of Le Fort I Fractures. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2024, 17, 51. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875241278796

Cho J-y, Ryu J. Management of Le Fort I Fractures. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2024; 17(4):51. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875241278796

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Jin-yong, and Jaeyoung Ryu. 2024. "Management of Le Fort I Fractures" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 17, no. 4: 51. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875241278796

APA StyleCho, J.-y., & Ryu, J. (2024). Management of Le Fort I Fractures. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 17(4), 51. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875241278796