Introduction

Maxillofacial trauma is 1 of the most common injury patterns reporting to the emergency department with a staggering high prevalence rate of 56.8%. The average annual incidence rate documented was as high as 20.4%[

1]. The patients reporting to the emergency department (ED) with maxillofacial trauma and associated injuries present with a myriad of complex injuries, making the comprehensive diagnosis and treatment plan challenging.

A structured documentation of these injuries provides a chronological sequence of the trauma and the associated factors, the primary care given, help in diagnosis and evaluation for further effective management and thus improves the overall quality of the care given to the patients. It further helps in averting delayed complications such as neurological deficits, suboptimal fracture healing, and the associated morbidities.

The ED notes becomes even more vital during patient care transition to other interdisciplinary departments, and poor quality notes often results in unnecessary delays and medical errors. Increase in the volume of the patients in tertiary centres, seasonal variations in maxillofacial trauma [

2], scarcity of health care professionals in patient care, complexity of the cases, time pressure, underexposure of the doctors to the complex cases, unstructured medical notes, illegible handwriting leads to poor documentation of medical records [

3]. The paucity of thorough understanding and specific training measures for the junior grades in trauma management including the ophthalmic injuries can lead to poor documentation of the findings and significantly affect the treatment outcomes [

4].

Midface fractures are often associated with ophthalmic injuries with prevalence of more than 90% [

5]. Ocular injuries associated with midface fractures can range from mild corneal abrasions to severe globe rupture and visual impairment with incidence of 1.5%–3% [

6]. Examination of the maxillofacial injuries must include measures to thoroughly evaluate the ophthalmic injuries to effectively reduce the associated morbidity and the quality of life of these patients. A retrospective audit study by Tahim et al. [

7]. reported the documentation of visual acuity in only 16.5% of the patients presenting with orbital wall or zygoma fractures. Early diagnosis of ophthalmic injuries helps in prompt ophthalmic intervention in high risk midface fracture pattern, thereby resulting in better vision outcomes [

8]. Patients presenting with wounds to emergency department are usually poorly documented, which can lead to improper management and present with high probability of litigation [

9]. especially if the mechanism of injury is an assault or occupational injury. The use of a structured encounter forms have shown to improve the overall completeness of the wound care documentation in pediatric emergency department [

10].

A significant proportion of patients reporting to the emergency department present with dental injuries. In a study on paediatric patients with maxillofacial and dental trauma, Saleh Zaid Al Shehri et al documented 26% of the patients with teeth avulsion of 223 patients who presented in the emergency department [

11].

There exists lacunae in literature regarding the enhancement of clinical examination accuracy in maxillofacial trauma using a trauma template. The role of structured trauma template has been documented to be less time consuming [

12], simplifies the examination findings documentation, and also helps in better representation and communication of the fractures among the surgeons; but its role in maxillofacial trauma is yet to be reported.

Literature review in urology highlights the importance of medical records in litigation, these form an integral part in medico-legal cases as the medical record is a valid document in the court of law [

13].

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the quality of the emergency notes of the maxillofacial trauma cases using a structured maxillofacial trauma template. The study also evaluated the quality of ophthalmic findings documentation in the maxillofacial trauma patients.

Methods

Study Design and Ethical Approval

A single centre, prospective pre-post study was conducted at a tertiary care institute after getting approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Settings and Consent

All the Oral and Maxillofacial trauma patients presenting to the emergency department were included in the study after primary stabilization. The eligibility criteria were followed for recruitment into the study for evaluation. All the procedures done for this study complied with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Hypothesis of the Study

Maxillofacial trauma template helps in improving the clinical examination accuracy compared to unstructured free hand documentation.

Eligibility Criteria

- (a)

Inclusion criteria: All patients of any age presenting with oral and maxillofacial trauma, along with other associated injuries. The study also included patients with any associated comorbidities.

- (b)

Exclusion criteria: Patients with conditions that could impact outcome assessment (eg, cognitive impairment). The study also excluded patients who were intubated. The patients who did not give consent for participation in the study were excluded.

Sample Size Calculation

A convenient sample was taken including maximum number of patients in a stipulated time frame from September 2023 to till February 2024.

Methodology

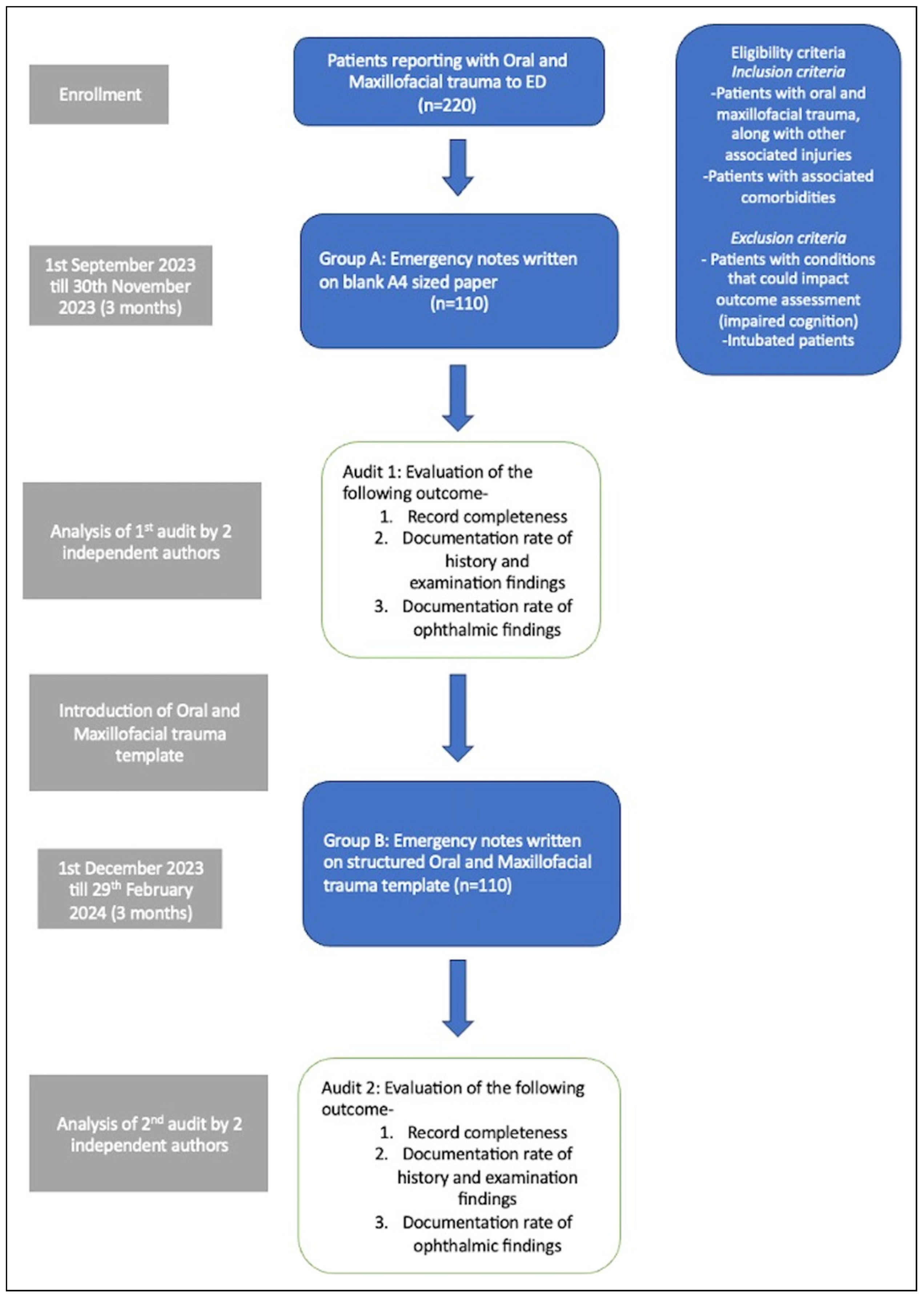

All the patients presenting with oral and maxillofacial trauma to the emergency department were evaluated. The patient’s demographic data, presenting findings, clinical and radiological evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment given were evaluated and documented precisely for each patient for a 6 months period. The flowchart of the study is shown in

Figure 1.

The patients were divided into following groups:

Group A (control): Documentation of maxillofacial trauma in ED without template

Group B (oral and maxillofacial trauma template): Documentation of oral and maxillofacial trauma in ED with template.

In group A, complete medical documentation was done routinely on a blank A4 sized paper, as it allowed detailed description without space constraints.

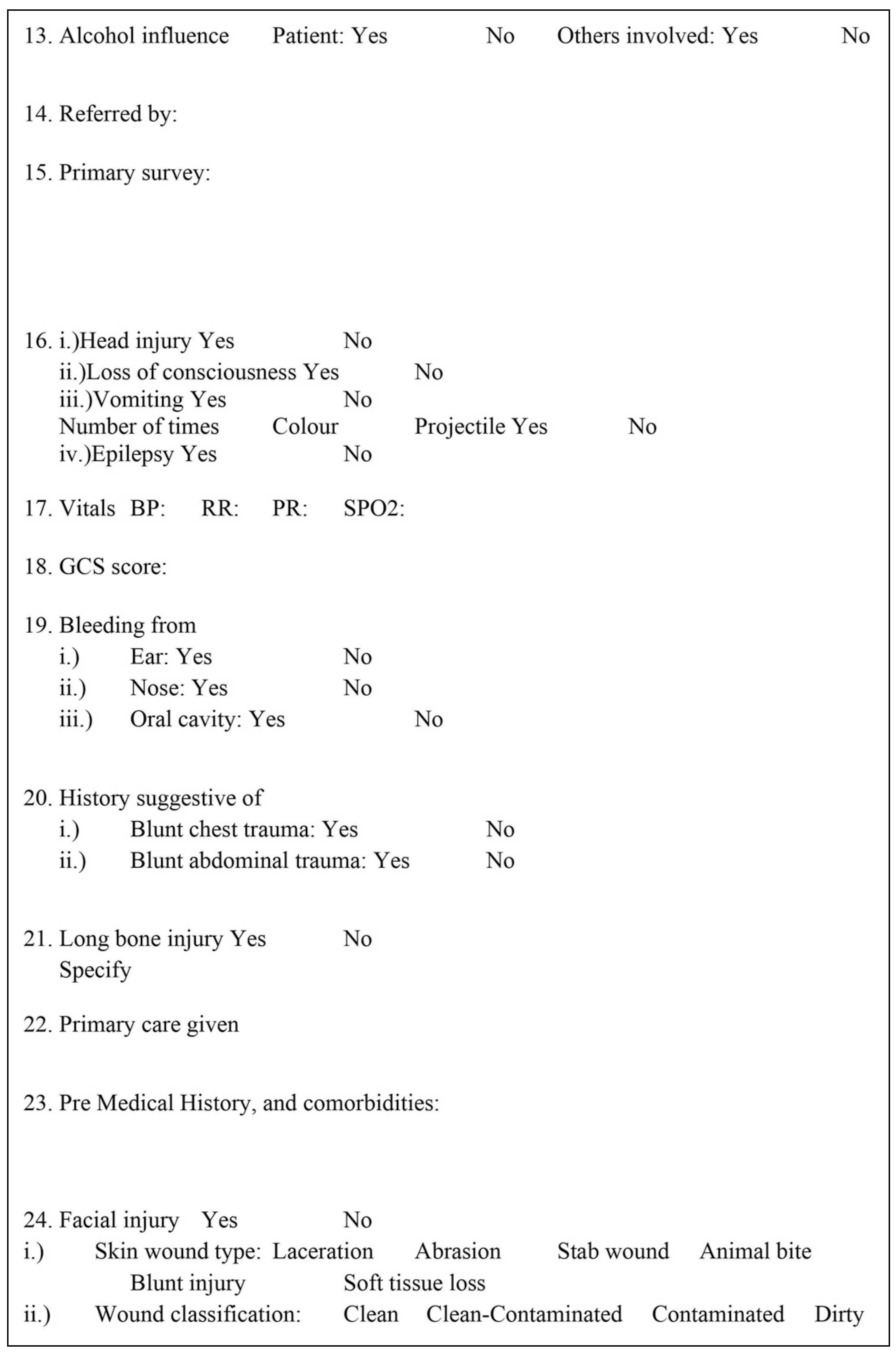

In group B, documentation was done using the new structured oral and maxillofacial trauma template (

Figure 2).

Data Collection and Assessment

The quality of ED documentation was assessed with the help of 2 outcome variables; record completeness and documentation rate of history and examination findings.

The record completeness was assessed by evaluating the following 2 predictive variables:

Demographic Data. A set of 10 covariates were assessed for demographic data evaluation:

patient details, time of injury, date of injury, place of injury, mechanism of injury, history of alcohol intake prior to injury, referral, date of evaluation, time of evaluation, primary care given.

Each covariate was given a score of 1; equal weightage was given for documenting positive as well as negative outcome in calculating the score.

Presentation & Treatment. Similarly, following 10 covariates were evaluated in this section:

wound type, wound classification, fractures, dentoalveolar injury, ophthalmic injury, associated injury, nerve injury, comorbidities, primary treatment given, and radiographic evaluation.

Scoring was done in a similar way like the demographic data, each covariate documented was given a score of 1.

Thus for each section in demographic data, and presentation & treatment, a maximum score of 10 each was calculated. Hence, a total maximum score of 20 was calculated for record completeness for a particular patient, thereafter expressed as percentage.

- (2)

Documentation rate of history and examination findings

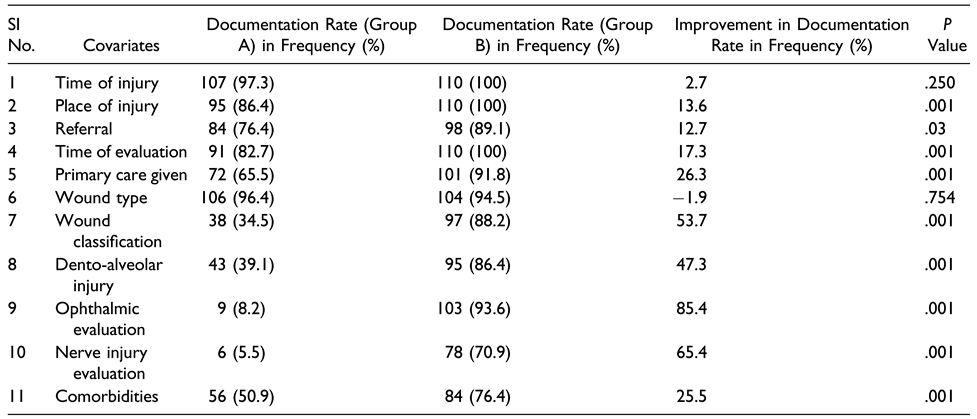

In documentation rate, a total of 11 important covariates were assessed:

time of injury, place of injury, referral, time of evaluation, primary care given, wound type, wound classification, dento-alveolar injury, ophthalmic evaluation, nerve injury evaluation, and comorbidity.

Each covariate amongst dento-alveolar injury, ophthalmic injury, nerve injury was considered as documented if there was excellent compliance in recording it.

Compliance 100% - excellent, compliance 80%–100% - Fair, compliance <80% - poor.

Outcomes Assessed

Primary Outcome

- (1)

To evaluate the record completeness of ED document.

Secondary Outcome

- (1)

To evaluate the documentation rate of history and examination findings.

- (2)

To evaluate the documentation rate of ophthalmic findings.

Statistical Analysis

The data collected for this study underwent thorough analysis utilizing IBM SPSS V.21. For every clinical feature, we calculated both the record completeness and documentation rate. A global score for record completeness was computed, giving equal weight to documented positive and negative findings. Additionally, the documentation rate, expressed as a percentage, was determined for each covariate, indicating the frequency of documented findings relative to the total number of clinical notes assessed. To assess the impact of changes over time, McNemar’s test was employed for comparing documentation rates between the 2 groups A, and B. A statistical significance threshold of p <.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 220 patients were included in the study, with 110 patients in each group. The mean age of the patients in group A was 29.21 ± 15.88 years, while it was 32.50 ± 14.62 years in group B. Male predominance was noted in the study with ratio of 92:18 in group A, and 97:13 male to female ratio in group B.

Group A included 110 patients, where documentation of the emergency notes was done on a blank A4 sized paper. Record completeness after the first audit was 74.19 %.

Group B included 110 patients, where documentation was done using structured oral and maxillofacial trauma template. Record completeness was 93.14 %, with improvement of 18.95% after the introduction of the structured template (

Table 1).

The demographic data showed an improvement of 8.36%, while the presentation & treatment subgroup demonstrated a 29.54 % improvement using the structured template (

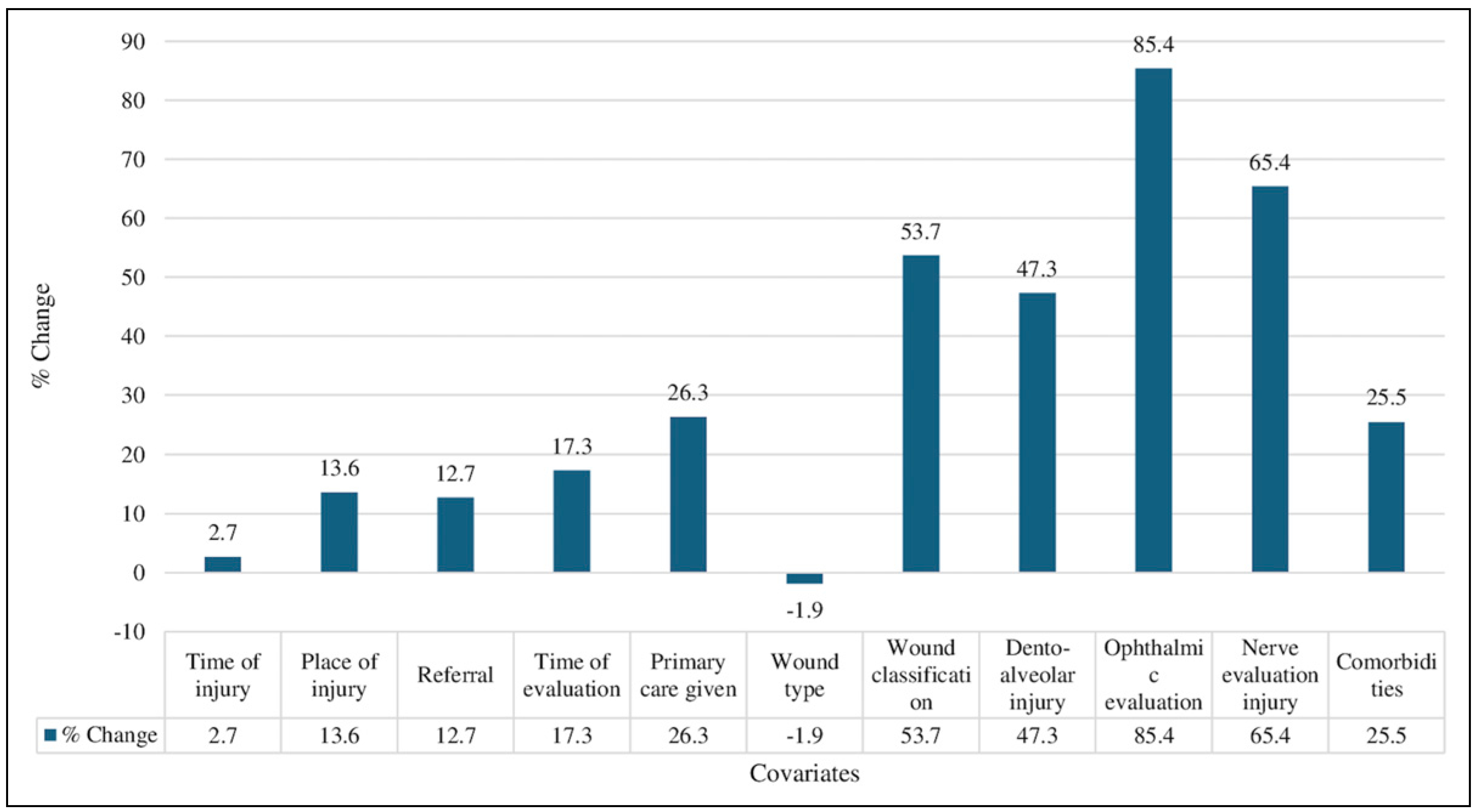

Table 1). There was statistically significant improvement in documentation rate (

Figure 3.) among the covariates like place of injury (

p = 0.001), referral (

p = 0.03), time of evaluation (

p = 0.001), primary care given (

p = 0.001), wound classification (

p = 0.001), dento-alveolar injury (

p = 0.001), ophthalmic evaluation (

p = 0.001), nerve injury evaluation (

p = 0.001), and comorbidities (

p = 0.001) (

Table 2).

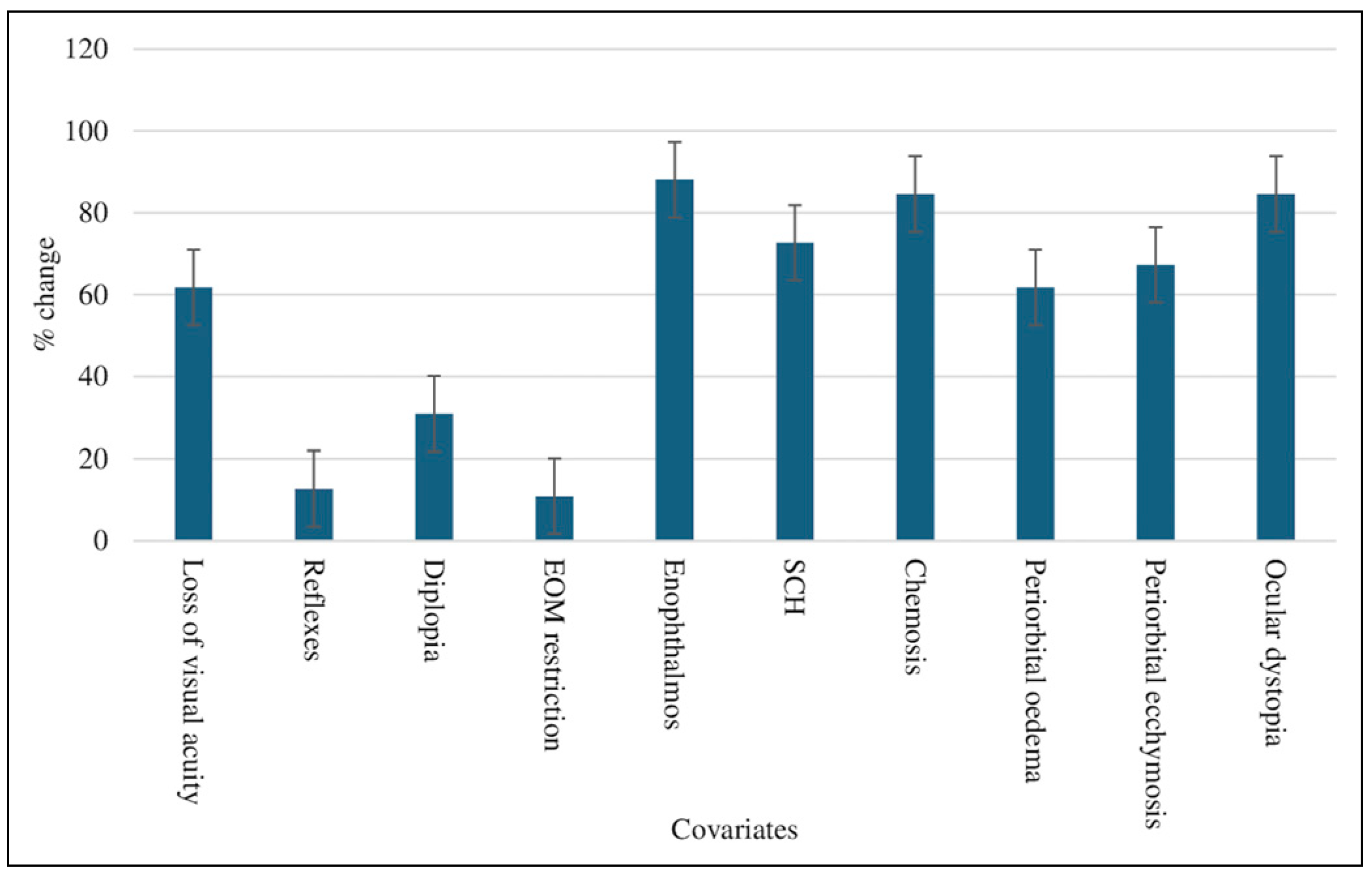

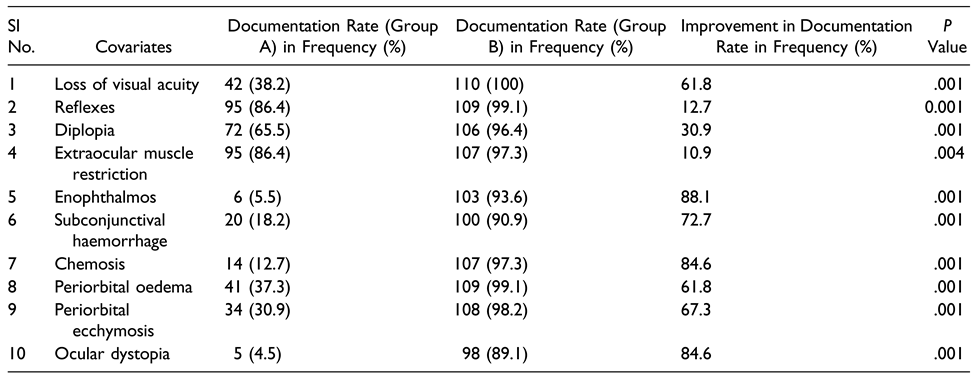

The ophthalmic evaluation also demonstrated statistically significant improvement (

Figure 4.) among all the covariates evaluated (loss of visual acuity, reflexes, diplopia, enophthalmos, subconjunctival haemorrhage ie, SCH, chemosis, periorbital oedema, periorbital ecchymosis, ocular dystopia) with

p = 0.001, while the documentation of extraocular muscle restriction showing improvement in documentation rate with

p = 0.004 (

Table 3).

Discussion

Complete, structured and precise documentation of trauma patients is essential to ensure they receive comprehensive, and timely care. The challenges in emergency department of managing the trauma patients quickly and efficiently along with involvement of interdisciplinary departments make the ED documentation quite an exacting task.

Our study aimed to identify the probing challenges, providing strategic solutions in the coherent documentation of ED.

The ED notes serve as an important medical document which is mostly used as reference point for further communication with other treating doctors and nursing staff [

14]. With increase in the number of maxillofacial trauma cases [

15], unconventional fracture pattern [

16], lack of comprehensive training in managing polytrauma cases [

17]. coupled with failure to understand the importance of detailed documentation of ED notes [

18]. lead to their underestimation thereby resulting in inadequate documentation.

A structured template for ED documentation not only ensures high quality record keeping, but also highlights the sequence of events and their appropriate management. There is scarce literature on the effectiveness of trauma template in enhancing record completeness. This study aimed to introduce a structured template and evaluate its usefulness in improving documentation quality.

Maxillofacial trauma due to road traffic accidents (RTA) are on continuous rise in India due to lack of adequate traffic regulations, non-compliance of safety measures, drunken driving, and poor infrastructure of roads [

15]. Our study reported high prevalence of maxillofacial trauma in males (97: 13 male to female ratio), and is consistent with studies by Amare Teshome et al. [

2]. and Zhou H et al [

5].

The mean age of the patients presenting with maxillofacial trauma was 29.21 ± 15.88 years in group A and 32.50 ± 14.62 years in group B, results of the study are similar to Amare Teshome et al [

2].

Significant improvement was seen in documenting demographic data like place of injury (

p = 0.001), time of evaluation (

p = 0.001), results of the study are similar to Gkiala [

19]. A et al. Recording these findings are extremely important in medico-legal cases as patients presenting to ED with injuries due to assault, occupational injury, RTA have high probability of litigation [

9]. and they rely on the findings of this documentation.

The results of our study show statistically significant improvement in documenting the important aspects of referral (

p = 0.003), and comorbidities (

p = 0.001) and is consistent with study by Enda Hannan et al. [

14], who reported significant improvement in documenting comorbidities (83% freehand vs 96% for structured format,

p = 0.0027).

The soft tissue injury to face account for nearly 10% of ED cases, thorough evaluation after following the principles of ATLS and early repair has reported improved functional and cosmetic results [

20]. The results of our study show significant improvement in documenting primary care given (

p = 0.001), and wound classification (

p = 0.001), however there was marginal yet insignificant decrease (1.9%,

p =.754) in documenting the type of the wound assessed. Similar results were studied by John T. Kanegaye et al. [

10], where they reported significant improvement in documenting completeness of paediatric wound management (80% structured form vs 68% for free text,

p < 0.001). The use of antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing the infection rate in trauma setting is quite common. Enrico Cicuttin et al [

21]. reported a decrease in infection rates among maxillofacial trauma patients through the implementation of shorter antibiotic regimens.

However, Jennifer C.E. Lane et al [

22]. reported no conclusive evidence supporting the use of prophylactic antibiotics in the management of small soft tissue lacerations.

The risk of ocular injury with maxillofacial fracture is 6.7 times compared to the patients with no facial fracture. C M Guly et al [

23]. in their retrospective analysis reported 9.8% eye injury in the patients presenting with facial fracture (398 out of 4082 facial fracture).

The present study evaluated the important ophthalmic parameters assessed in the ED and found statistically significant improvement in documenting loss of visual acuity p = 0.001, reflexes p = 0.001, diplopia p = 0.001, enophthalmos p = 0.001, subconjunctival haemorrhage p = 0.001, chemosis p = 0.001, periorbital oedema p = 0.001, periorbital ecchymosis p = 0.001, ocular dystopia p = 0.001, and extraocular muscle restriction with p = 0.004. The use of structured trauma template improved the documentation of ophthalmic evaluation by 85.4% with p = 0.001.

The results of the study are similar to Simon Haworth et al, where they used structured record keeping tool and thus reported significant improvement in visual acuity, reflexes, diplopia, subconjunctival haemorrhage and enophthalmos with

p < 0.001 [

4].

The incidence of ophthalmic injury varies with the type of fracture pattern. Gaurav Mittal et al [

24]. reported 34.5% of the mandibular fractures, 25% of the nasal fractures, 95.7% of the mid face fractures, and 83.3% of the frontal fractures to be associated with ocular injury of varying severity. Their study showed 29.09% of the maxillofacial trauma patients with transient or permanent visual loss, emphasising the importance of ophthalmic evaluation in the maxillofacial trauma patients. While ocular injuries may not necessarily impact the surgical treatment plan for midface fractures, they do influence the timing of ophthalmic intervention. Delaying immediate intervention could lead to significant risk of complications as evidenced by Satish Kumar Patil et al [

25]. Thus it is imperative for the maxillofacial surgeons to have thorough understanding and sufficient training in ophthalmic injuries that occurs concomitantly with maxillofacial traumas.

Injuries of the facial and/or trigeminal nerve occurs frequently with facial trauma. Their evaluation should always procced management of soft tissue/hard tissue injuries in the ED. The ophthalmic evaluation of the trauma patients should be done in conjugation with assessment of neurosensory deficit of the infra-orbital nerve [

25]. Behnaz Poorian et al [

26]. in their study of 495 patients with maxillofacial trauma, reported marginal mandibular branch to be involved in 1%, inferior alveolar branch of trigeminal nerve in 39.1% and infraorbital branch of trigeminal nerve in 27.2% of maxillofacial trauma cases.

The results of our study demonstrated significant improvement in nerve injury evaluation with the structured trauma template (6% no template vs 78% with template) with statistically significant result (65.4% improvement, p = 0.001).

Most of the paediatric maxillofacial injuries reporting to the ED are due to dentoalveolar fractures (42.1%) [

27] and soft tissue injuries. Saleh Zaid Al Shehri et al, reported 25% incidence of dental trauma in the form of teeth avulsion, luxation, and crown fracture in the paediatric emergency unit which requires urgent diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in form of re-implantation of tooth, reduction of displaced teeth to reduce unfavourable functional and aesthetic outcomes [

11].

The results of our study show statistical significant improvement of 47.3% in reporting dento-alveolar injury when using the structured trauma template (p = 0.001).

Our study showcased enhanced record completeness and documentation rates of history and examination findings when utilizing a structured trauma template compared to unformatted freehand documentation. The ED notes are not only reflection of the care rendered to the patients but also serve as a valuable tool for future audit and research, provides valuable evidence in medico-legal cases [

28]. and is used to communicate with interdisciplinary departments. Pre-printed structured templates have reported to have a positive impact on doctors’ performance [

29]. Using the template, doctors are more likely to detect adverse events, provide improved patient safety and are more preferred compared to freehand notes [

30].

Various methods like regular audits, early strategic and focussed training of the residents in ophthalmology and trauma setup, understanding the importance of well documented ED notes and medico-legal aspects can be used to improve the quality of ED documentation.

The strength of the study includes its objective nature, sample size, detailed description of the ophthalmic and dento-alveolar injury, and elimination of recall bias. Our study is not without caveats and limitations. The study aimed to document only the presence/absence of the findings without attempting to evaluate their incidence. The use of structured template also limits the free expression of the doctors.