Results

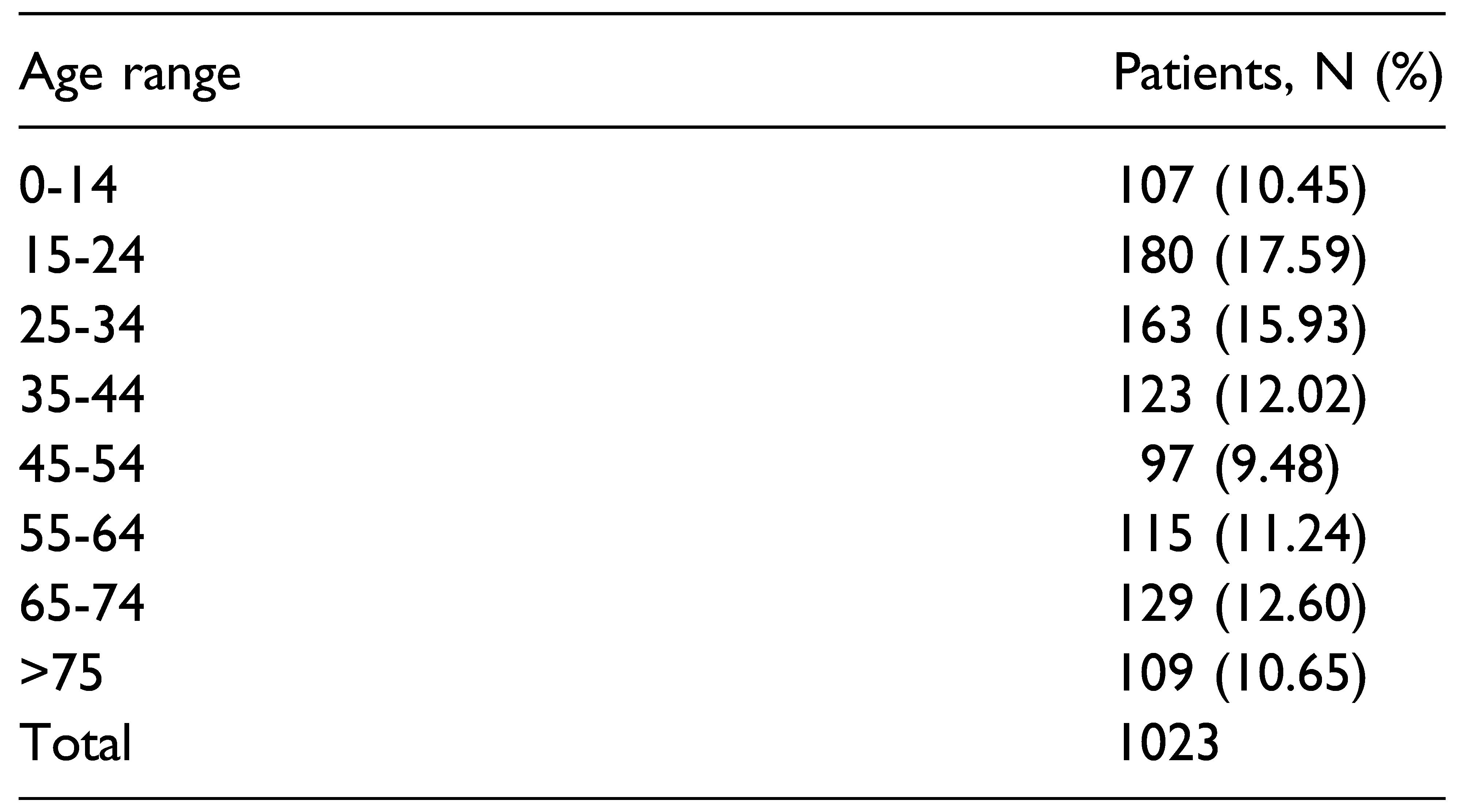

Among patients, 684 were male (66.86%) and 339 were female (33.13%). The average age of the patients was 42, 38 years (ranging from 7 to 94 years). Patients were divided into 8 groups according to age (10 years intervals) with a separate group to include pediatric patients (0-14 years): 107 patients (10.45%) were younger than 14 years. 180 patients (17.59%) were between 15 and 24 years of age, 163 (15.93%) between 25 and 34 years, 123 (12.02%) between 35 and 44 years, 97 (9.48%) between 45 and 54 years, 115 (11.24%) between 55 and 64 years, 129 (12.60%) between 65 and 74 years, and 109 patients (10.65%) were older than 75 years (

Table 1).

Mandibular parasymphysis fractures were the most frequent (34.1%), followed by condylar fractures (27.8%) and angle fractures (18.3%). The percentage of remaining fractures is divided between symphysis, body, branch fractures, and condyle fractures. The latter are in turn divided into 3 categories such as condylar head, high neck and low neck fractures.

Concerning the type of fracture, we mainly witnessed simple, moderately displaced and closed fractures. Green stick fractures were mainly found in children (n = 29). However, pluricomminute, atrophic, complicated, open fractures were less frequent. Multiple fractures at the mandibular level have been reported in 198 cases (19.35%) mainly involving the mandibular parasymphysis and the condyle or the contralateral angle.

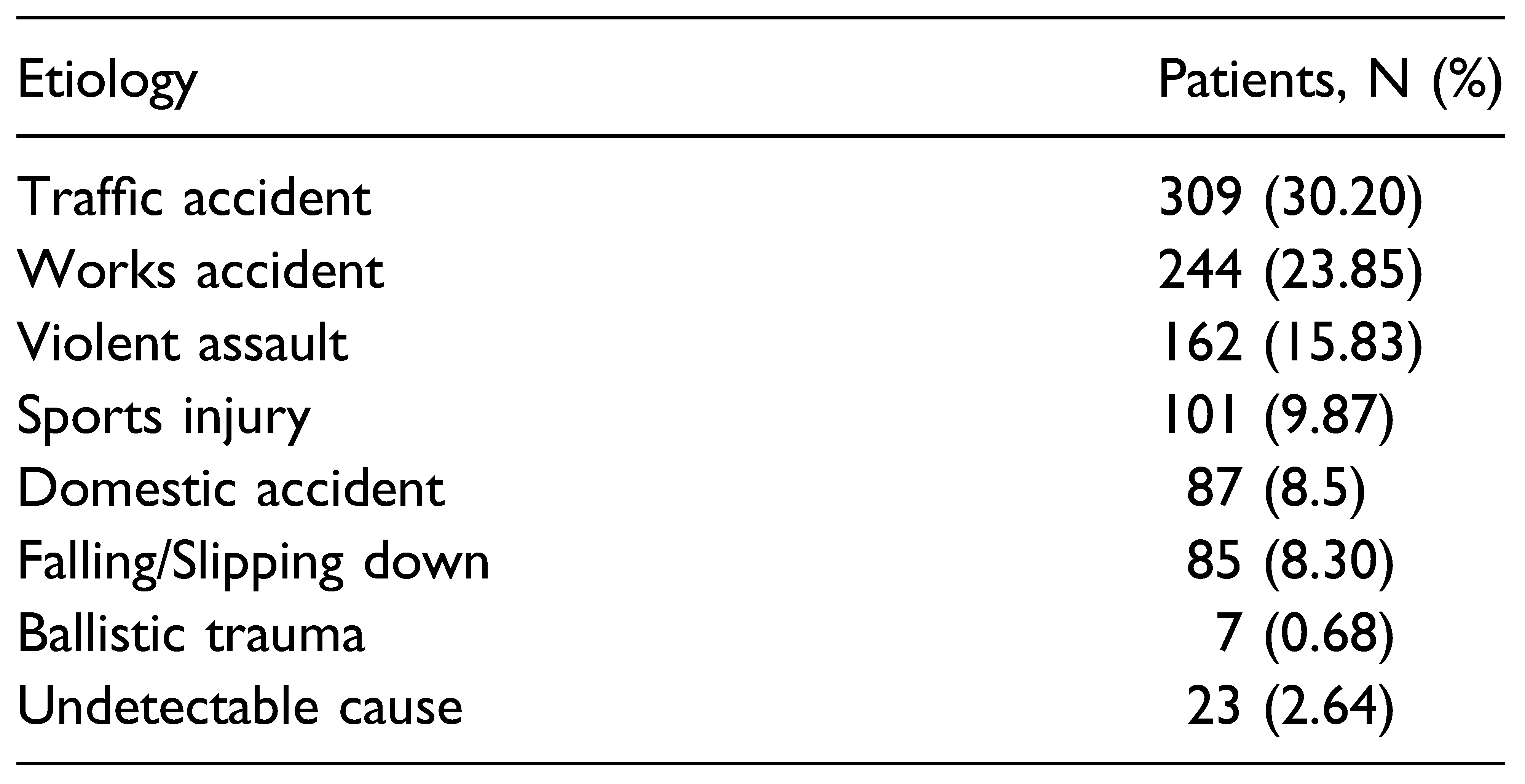

The principal etiology of mandibular fractures was traffic accidents (n = 309; 30.20%), followed by accidents at work (n = 244; 23.85%), violent assault (n = 162; 15.83%), sports-related injury (n = 101; 9.87%), domestic accidents (n = 87; 8.5%), falling down (n = 85; 8.30%), and ballistic trauma (n = 7; 0.68%) (

Table 2).

We reported 23 patients (2.64%) with unknown causes as undeclared or due to errors in medical history.

Violent assault was the leading cause of mandible fractures among male patients; traffic accidents were most common in female; accidental falling was the most frequent cause in older patients (>75 years) and sport-related injuries were the most common cause in male patients aged between 0 and 35 years.

Systemic traumatic involvement was reported in 57 patients (5.27%): 27 patients had polytrauma, 11 had cerebral trauma, and 16 had fractures of other skeletal elements.

148 patients presented concomitant facial wounds and 184 patients were affected by other facial fractures (136 COMZ fractures, 27 nasal bone fractures, 7 frontal sinus fractures, and 14 Le Fort type I fractures).

The most frequent clinical signs and symptoms were: malocclusion, difficulty in chewing, limitation of the buccal opening, hypoesthesia in the region innervated by the inferior alveolar nerve, difficulty in protrusion movements and mandibular lateralization.

Clinical follow-up was performed after 7 days, 3 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months post-treatment.

The mean ± standard deviation of time interval between trauma and surgery was 3 ± 4 days. Open reduction surgery of the mandibular fracture was performed in most cases. In the remaining cases rigid intermaxillary locking was performed for an average of 16 days and it was followed by elastic intermaxillary locking. The surgical approach was mainly intraoral, except for the treatment of condylar fractures which involved submandibular or preauricular access.

Titanium plates and screws (mandible fracture 2.0 system) were mainly used. In 37 cases, plates and screws of the mandible reconstruction system were used according to the load-bearing principle, due to the multiple joint entity of the mandibular fracture or due to the patient predisposition (mandibular atrophy, pathological fracture, etc.).

Postoperative complications occurred in 121 patients (11.82%). Immediately after surgery 45 patients had hypoesthesia/anesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve, 22 patients had persistent malocclusion, 9 patients had suboptimal healing, 16 patients showed mandibular movement difficulties, and 29 patients had plate exposition and infection.

Among 121 patients, 63 had persistent sequelae after 6 months: 41 inferior alveolar nerve hypoesthesia, 15 scar outcome, and 7 limitations of mandibular kinetics.

93% of patients underwent surgery under general anesthesia, almost exclusively patients undergoing an open approach to internal fixation. The remaining 7% are patients who underwent intermaxillary locking performed as an outpatient procedure or day-hospital treatment under local anesthesia. In patients undergoing surgery with the open technique, antibiotic prophylaxis was performed as per company protocol (Cefazolin + Metronidazole, modified according to any intolerances and allergies).

Reoperation was performed successfully in 35 patients (3.4%) mainly because of residual malocclusion in the immediate postoperative period, imperfect reduction of the fracture shown by the control CT, infection of the early fixation devices.

Discussion

Although the jaw is 1 of the heaviest and most resistant bone in the human body, fractures of the jaw are 1 of the most common facial skeletal injuries. The main reasons for this statistic consist in the fact that it is the most caudal structure of the face and therefore it is more exposed to trauma, it is an unequal arch-shaped bone, it can be particularly weakened in the process of atrophy in accordance with the advancement of the age of the patient and it may be affected by pathological fractures in patients with malignant neoplasms of the oral cavity.

In literature, there are heterogeneous studies regarding epidemiology, demographic and clinical characteristics of patients, type of surgical approach, materials, and timing to perform surgery.

The purpose of this retrospective study on patients who came to our department for mandibular fracture is to evaluate, over the observed 10-year period, the main causes of trauma, the main fracture patterns of the mandibular bone and which types of treatment were most applied.

In our department, we reviewed 1023 patients with mandible fractures, excluding patients who have already undergone surgery. The patients in the present study were evaluated by age, sex, etiology, symptoms, comorbidities, fracture type, treatment, time to surgery after trauma, complications, and sequelae.

It is important to consider that the total population of the Marche region amounts to about 1 million and 400 thousand inhabitants and that our department represents the reference center for cervical-facial pathology.

In most studies, males are more often affected compared to females. This might be due to a greater participation in outdoor activities and to higher levels of physical activity in males. Furthermore, males are more likely to be involved in traffic accidents [

1,

2,

3].

In our report, 684 patients were men (66.86%) and 399 were women (33.13%) and the male/female ratio was about 2:1. The sex ratio observed in other studies was 3:1, 4: 1 [

4].

In a study by Shah et al, the peak age group for mandibular fractures was 21-30 years [

5,

6].

In our study the largest number of patients we got was in the 15-24-year age group (17.59%) and the 25-34-year-old group (15.93%).

The average age of the patients was 42, 38 years (ranging from 7 to 94 years).

Fractures of the facial skeleton in children account for only 4.9% of all facial fractures in the population, most frequently between the ages of 5 and 13 years. In children, the most common maxillofacial fracture sites are the nose and the dentoalveolar complex, followed by the mandible, orbit, and midface. Among the mandibular fractures, the involvement of the condyle occurs in 43.3% to 72% cases [

7].

Several studies about non-surgical fracture management in children confirmed that closed functional treatment has excellent results based on the patient’s growing potential to reshape the condylar head and to restore function.

There have been several publications on the causes of jaw fractures including assaults, traffic accidents, workrelated injuries, falls, sports injuries, pathological fractures, and gunshot injuries [

8,

9].

Among those living in the city, the most frequent cause of mandibular fracture is represented by struggles and road accidents.

Young and male subjects are almost universally victims of facial trauma more frequently than women, and in many countries alcohol is often a significant contributor.

Sports injuries are more common in young male adults between the ages of 10 and 30. The main sport identified as a cause of injury was football, followed by basketball and rugby. In our patients, traffic accidents represent the principal cause of mandibular fractures (n = 309; 30.20%), followed by accidents at work, most common in the male patients (n = 244; 23.85%), violent assault (n = 162; 15.83%), sports-related injury (n = 101; 9.87%), domestic accidents (more frequent in the females) (n = 87; 8.5%), falling down (n = 85; 8.30%), and ballistic traumas (n = 7; 0.68%).

Accidental falls are more frequent in older patients and especially in the age group over 75 years.

The most common type of mandibular fracture in our study was that of parasymphysis with 348 cases (34.1%), followed by condyle fractures with 289 cases (28.25%), mandibular angle fractures with 187 cases (18.3%), symphysis fractures with 81 cases (7.9%), body fractures with 71 cases (7%), mandibular ramus fractures with 20 cases (2%), midline fractures with 18 cases (1.7%), and coronoid fractures with 12 cases (1.2%).

A higher incidence of left-sided mandibular fractures was found mainly in those patients who are victims of aggression, due to punches received in the face by mostly right-handed aggressors.

We reported that single fractures were found in 825 patients (80.65%) and multiple mandible fractures were seen in 198 cases (19.35%).

The most frequent combination in bifocal or trifocal fractures was parasymphysis and condyle (9.3%) which is similar to studies done by Natu et al. The result we have obtained is different from many studies which have shown that the most common combination is the parasymphysis and the angle. Ogundare et al have reported the combination of mandible body with the angle of the mandible [

3,

10].

According to larger case series reported in the literature, fractures of the mandibular condyle account for an important percentage of all mandibular fractures.

Approximately 82% of condylar fractures are unilateral and the most frequent causes are assaults, traffic injuries, accidental falls, and sports injuries. According to Silvennoinen et al, approximately 14% of condylar fractures are intracapsular, 24% are condylar neck fractures, 62% subcondylar fractures, and 16% are associated with remarkable displacement. The highest incidence for this type of fracture was seen between the ages of 19 and 40 [

11,

12].

In accordance with the Strasbourg Osteosynthesis Research Group (SORG) classification of condylar fractures is represented by: (A) high or condylar neck fracture; (B) low or condylar base fracture; (C) diacapitular fracture.

In our series, we specifically recorded, from the total number of 289 condyle fractures, 57 condyle head fractures (5.7% of the total mandibular fractures), 77 high condylar neck fractures (7.3%) and 155 low condylar neck (14%) [

13].

Systemic injuries have been reported in 57 patients (5.27%): 27 patients had polytrauma, 11 had cerebral trauma and 16 had fractures of other skeletal elements.

Clinical and radiographic analysis revealed 148 patients with concomitant facial wounds and 184 patients with associated facial fractures (136 COMZ fractures, 27 nasal bone fractures, 7 frontal sinus fractures, and 14 Le Fort type I fractures).

The most common clinical signs and symptoms were malocclusion, pain and difficulty on talking and swallowing, trismus and difficulty in moving and opening the jaw, hypoesthesia in the anatomical area innervated by the inferior alveolar nerve, difficulty in protrusion and mandibular lateralization movements, sublingual hematoma, mobility of fractured segment, tinglin of the lower lip, loosened teeth, medial or lateral displacement of the condyle and trigeminal nerve injury.

Fractures should theoretically be treated as soon as possible but this is not always possible. For all open fractures (e.g., fractures associated with a tissutal laceration, or involvement of the periodontium), it is possible to say with certainty that the risk of infections is directly proportional to the time that elapses between the trauma and the surgery infections.

However, in literature the time frame beyond which the risk of complications or suboptimal surgical results significantly increases is not well understood [

14,

15].

We recorded that 89% of patients were treated within 5 days from the traumatic event.

The time between the injury and surgery depends on factors such as good clinical condition to tolerate a surgical procedure and the admission time of the patient [

16,

17].

Whatever type of treatment is chosen the main goals to be achieved are: anatomical reduction of the fractures, stability and healing, restoration of pre-injury stable occlusion, recovery of mandibular movements, retainment of the face symmetry, avoidance of complications such as infections, malunions or nonunions and nerve injuries.

Treatments generally vary according to the fracture type, the number and the location, surgeon preferences and patient characteristics (age, dental profile, choice of treatment, etc.).

In case of displaced or multi-comminuted fractures, there are a number of possible surgical options to consider:1. Intermaxillary fixation with wire or elastics (closed techniques); 2. Open reduction and internal fixation via transoral approach; 3. Open reduction and internal fixation via transcutaneous approach; 4. External fixation [

18,

19].

In the present study 841 patients underwent open reduction and internal fixation which involved the use of miniplates, monocortical screws or transosseous wiring, or combination of these. Non-surgical management was followed in 182 patients, which included the use of arch bars, Ivy loops and rigid or elastic intermaxillary fixation.

Due to the multiple joint entity of the mandibular fracture or due to the patient’s predisposition (mandibular atrophy, pathological fracture, etc.) plates and screws of the mandible reconstruction system were used according to the load-bearing principle in 37 cases.

Closed reduction was performed only in selected cases, taking into account the patient age, the extent of any fracture displacement, the medical conditions, and the patient preferences.

Regarding condyle fractures in adult patients there are some specific absolute indications for the treatment of open reduction and internal fixation of condylar fractures (ORIF): displacement into the middle cranial fossa or external auditory meatus, inability to achieve stable occlusion without surgery, presence of foreign bodies or severe contamination, lateral or medial extracapsular displacement of bone fragments [

20].

On the other hand, a non-surgical, conservative approach may be considered the best option in cases of: condylar neck fractures in children <12 years of age; high condylar neck fractures without fragment displacement; intracapsular (diacapitular) condylar fractures; loss of ramus height.

The surgical solution was the most applied in our department for the management of this type of fractures.