Trends in Maxillomandibular Fixation Technique at a Single Academic Institution

Abstract

Introduction

Materials and Methods

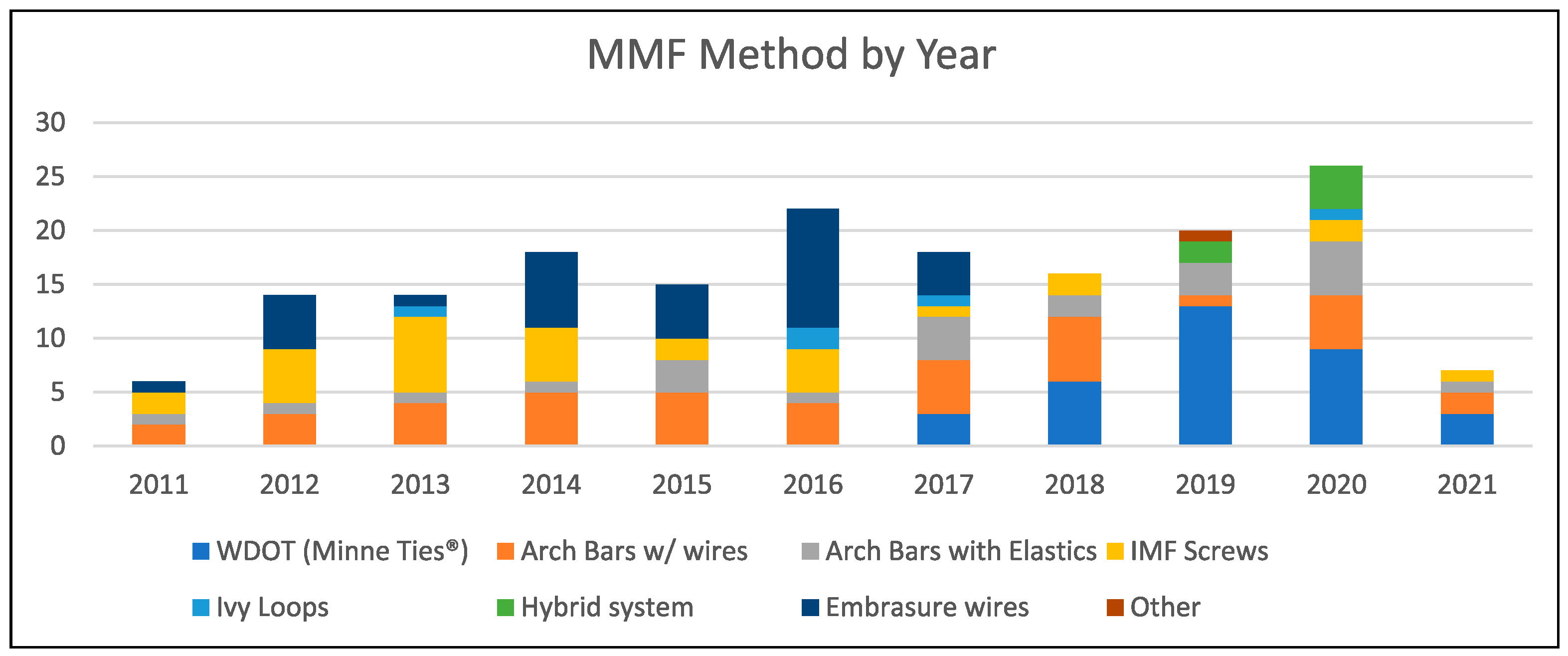

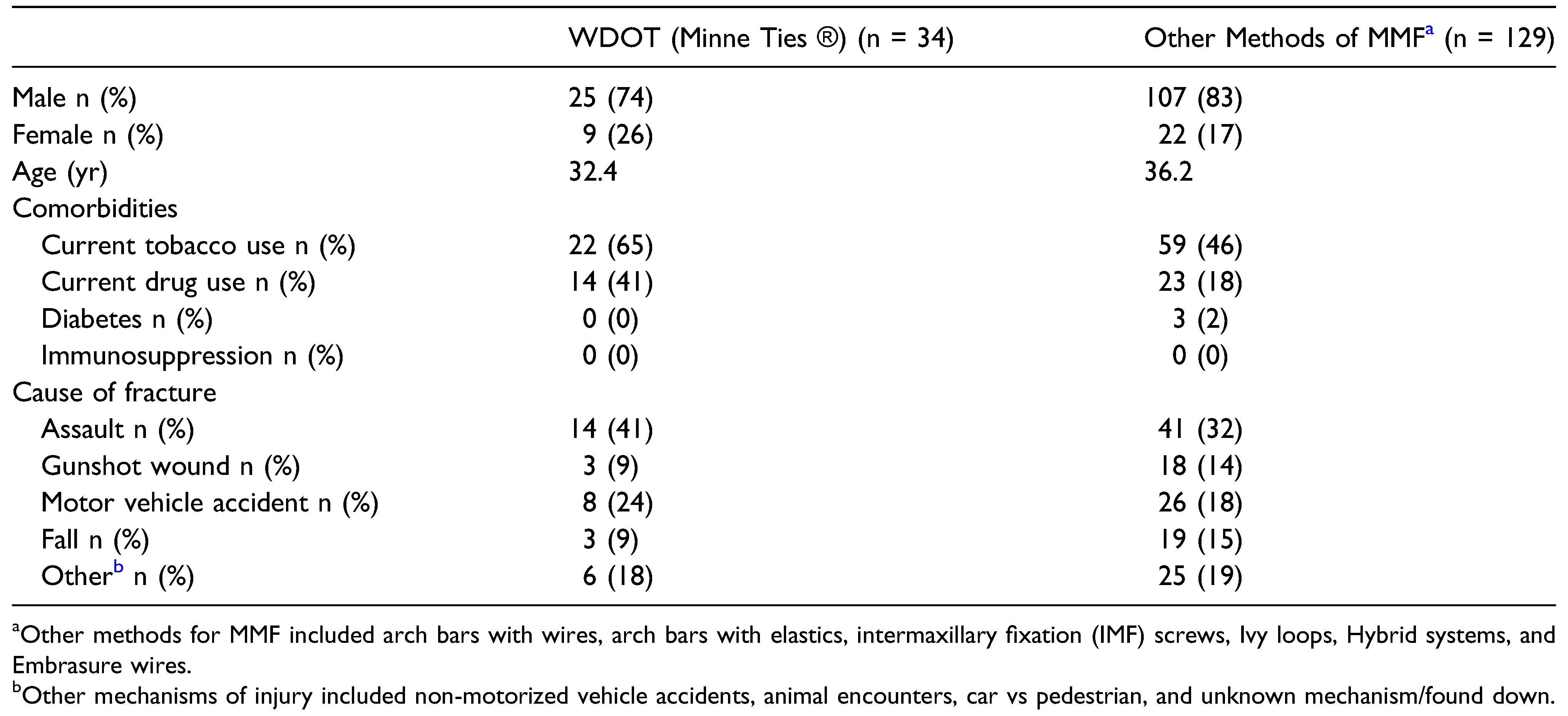

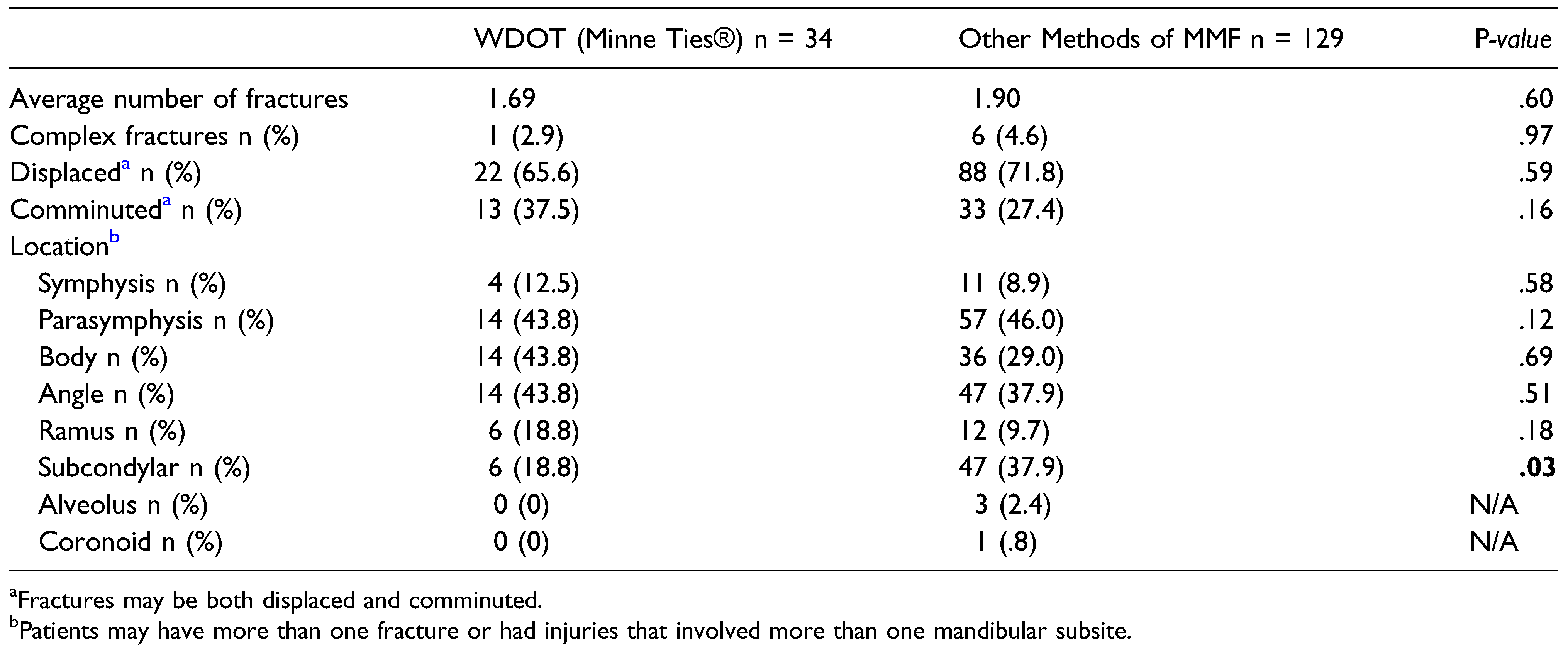

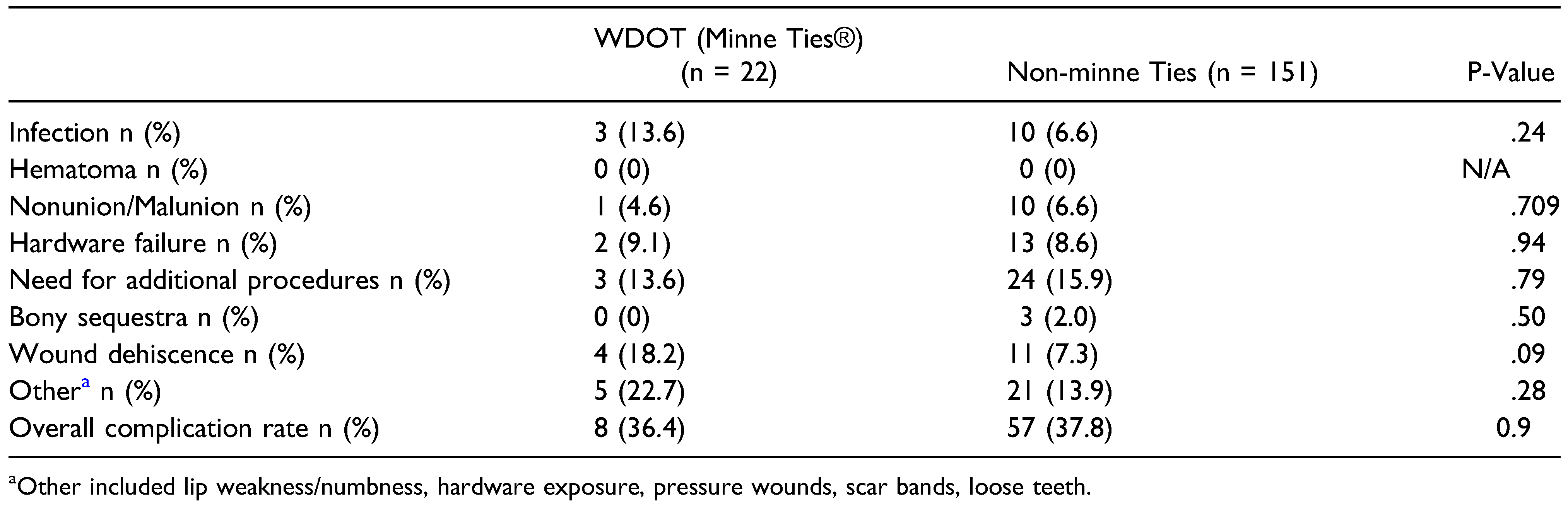

Results

Discussion

Funding

Author’s Note

Declaration of conflicting interests

References

- Capizzi, P.J.; Bite, U.; Arnold, P.G.; Woods, J.E. John B. Erich, D.D.S., M.D. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997, 99, 1473–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convers, J.M. Robert H. Ivy, M.D., D.D.S. A tribute. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973, 51, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivy, R. Observations of fractures of the mandible. JAMA 1922, 79, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.W. Dental occlusion ties: a rapid, safe, and non-invasive maxillo-mandibular fixation technology. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017, 2, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.; Jain, A. A technique for intraoperative maxillomandibular fixation. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017, 21, 485–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falci, S.G.; Douglas-de-Oliveira, D.W.; Stella, P.E.; Santos, C.R. Is the Erich arch bar the best intermaxillary fixation method in maxillofacial fractures? A systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2015, 20, e494–e499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farber, S.J.; Snyder-Warwick, A.K.; Skolnick, G.B.; Woo, A.S.; Patel, K.B. Maxillomandibular fixation by plastic surgeons: cost analysis and utilization of resources. Ann Plast Surg. 2016, 77, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendrick, D.E.; Park, C.M.; Fa, J.M.; Barber, J.S.; Indresano, A.T. Stryker SMARTLock hybrid maxillomandibular fixation system: clinical application, complications, and radiographic findings. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016, 137, 142e–150e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.; Datarkar, A.; Borle, R.M. Are maxillomandibular fixation screws a better option than Erich arch bars in achieving maxillomandibular fixation? A randomized clinical study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011, 69, 3015–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roeder, R.A.; Guo, L.; Lim, A.A. Is the SMARTLock hybrid maxillomandibular fixation system comparable to intermaxillary fixation screws in closed reduction of condylar fractures? Ann Plast Surg. 2018, 81, S35–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.J.; Christense, B.J. Hybrid arch bars reduce placement time and glove perforations compared with erich arch bars during the application of intermaxillary fixation: a randomized controlled trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019, 77, e1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.S.; Graham, R.M. Perils of intermaxillary fixation screws. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020, 58, 728–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelstad, M.E.; Kelly, P. Embrasure wires for intraoperative maxillomandibular fixation are rapid and effective. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011, 69, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satpute, A.S.; Mohiuddin, S.A.; Doiphode, A.M.; Kulkarni, S.S.; Qureshi, A.A.; Jadhav, S.B. Comparison of Erich arch bar versus embrasure wires for intraoperative intermaxillary fixation in mandibular fractures. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018, 22, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, K.; Gutta, R. Are embrasure wires better than arch bars for intermaxillary fixation? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015, 73, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam-Pervez, N.; Caccamese, J.F., Jr.; Warburton, G. A randomized prospective comparison of maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) techniques: “SMARTLock” hybrid MMF versus MMF screws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2020, 130, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

© 2023 by the author. The Author(s) 2023.

Share and Cite

Schopper, H.; Krane, N.A.; Sykes, K.J.; Yu, K.; Kriet, J.D.; Humphrey, C.D. Trends in Maxillomandibular Fixation Technique at a Single Academic Institution. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2024, 17, 119-123. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875231176339

Schopper H, Krane NA, Sykes KJ, Yu K, Kriet JD, Humphrey CD. Trends in Maxillomandibular Fixation Technique at a Single Academic Institution. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2024; 17(2):119-123. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875231176339

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchopper, Heather, Natalie A. Krane, Kevin J. Sykes, Katherine Yu, J. David Kriet, and Clinton D. Humphrey. 2024. "Trends in Maxillomandibular Fixation Technique at a Single Academic Institution" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 17, no. 2: 119-123. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875231176339

APA StyleSchopper, H., Krane, N. A., Sykes, K. J., Yu, K., Kriet, J. D., & Humphrey, C. D. (2024). Trends in Maxillomandibular Fixation Technique at a Single Academic Institution. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 17(2), 119-123. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875231176339