Introduction

Patients with head and neck defects requiring reconstruction with microvascular free tissue transfer are usually at risk for malnutrition due to the nature of the disease [

1]. Malnutrition is defined as “inadequate nutritional intake and/or increased nutritional requirements that result in negative clinical outcomes” [

2]. Nutrition and wound healing are closely related. Nutrition deficiencies impede the normal processes that allow progression through specific stages of wound healing [

3]. Nutrient deficiencies or malnutrition can have negative effects on wound healing by prolonging the inflammatory phase, decreasing fibroblast proliferation, and altering collagen synthesis; malnutrition has also been related to decreased wound tensile strength and increased infection [

3]. Most importantly, free flap failure and delayed wound healing have been associated to various factors including age, diabetes, smoking history, and surgical time.

In patients with head and neck malignancies, the preoperative nutritional status was only considered good in 43%, while rated fair in 21%, and poor in 36%. Additionally, 50% of patient had more than 10% loss of their usual body weight, and 40% had decreased serum albumin levels [

4]. Literature shows that advanced age and cancer stage, frailty, dementia, major depression, functional impairment, and physical performance are important risk factors for malnutrition in older adults with head and neck tumors requiring reconstruction with free flaps [

5]. This creates a less than ideal healing environment after major head and neck surgery that puts these patients in a higher risk of developing surgical site infection, dehiscence, and delayed surgical site healing.

Worldwide guidelines recommend nutrition screening to identify patients at risk of malnutrition [

6]. This is not only because treatment of malnutrition has clinical benefits, but also because of the costs of malnutrition. Despite recognition of the importance of adequate nutritional screening, malnutrition remains under-detected and under-treated [

6].

In the last couple of decades, several screening tools have become available. Single parameter based nutritional risk assessment considering, for example, serum albumin and body max index. have been evaluated in the past but they were not precise in identifying patients at risk for malnutrition. Expert consensus recommends the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool because it uses combinations of various criteria as a more accurate method for assessing the risk for malnutrition [

7]. The Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST), developed by the British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN) [

8]. It’s a five-step screening tool to identify patients who are malnourished and at risk of malnutrition (or undernutrition) [

9,

10] is considered an appropriate malnutrition screening tool because it has face, content, concurrent, and predictive validity with a range of other screening tools [

11]. The purpose of this project is was to determine if the MUST as a preoperative assessment tool is useful to predict postoperative surgical site infection and delayed wound healing in subjects undergoing reconstruction with free flaps for head and neck defects and the second outcome was to determine the rate of partial or total flap failure in subjects at risk for malnutrition.

Materials and Methods

The authors designed and implemented a retrospective cohort study, which was approved by the University of Florida Jacksonville’s Institutional Review Board; it was designed to include all subjects who underwent head and neck microvascular free tissue transfer at a single institution between 2013 and 2019 with medical data 30 days postoperative. Primary and secondary reconstructions were included, for benign or malignant pathology, osteonecrosis, osteomyelitis, congenital defects, and trauma. Subjects were excluded if they had incomplete data in medical charts to calculate BMI, no data regarding history of loss of weight, no data regarding acute illness impairing nutritional intake or had died before postop day 30.

Variables collected describing the sample included demographics (Age, sex), medical (history of hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, lung disease, polypharmacy, mental health diagnosis and history of chemotherapy or radiation to head and neck), and social history (smoking and alcohol use). The BMI was calculated from the preoperative clinic appointment weight. BMI score was recorded as a categorical variable, either>20 kg/m2, 18.5–20 kg/m2 and <18.5 kg/m2. Weight loss in the last 6 months was also documented, defined as loss of <5% of BMI, loss of 5–10% of BMI or loss >10% of BMI. The acute illness affecting nutritional intake was documented, defined as subjects affected by and acute pathophysiological or physiological condition, and had no nutritional intake or likelihood of no intake for more than 5 days, including patients with swallow difficulties and BOT and large oral cavity tumors. The nutritional risk was then able to be evaluated using MUST, which analyzes body mass index, weight loss, and acute disease effect, to classify patients as low, intermediate, and high risk. We further divided the subjects into two comparison groups—a low-intermediate risk group and a high-risk group. The primary outcome was surgical site complications defined as surgical site infection and localized inflammatory signs and delayed wound healing defined as surgical wound dehiscence or skin breakdown after postop day 30 and the secondary outcome was total or partial flap loss. Descriptive statistics (mean, frequency, range, standard deviations) were computed for each study variable, Bivariate analyses (Chi-square, T-test) were computed to measure the association between any 2 variables of interest. P-values <.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were done utilizing IBM SPSS Statistics Version 29 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York).

Results

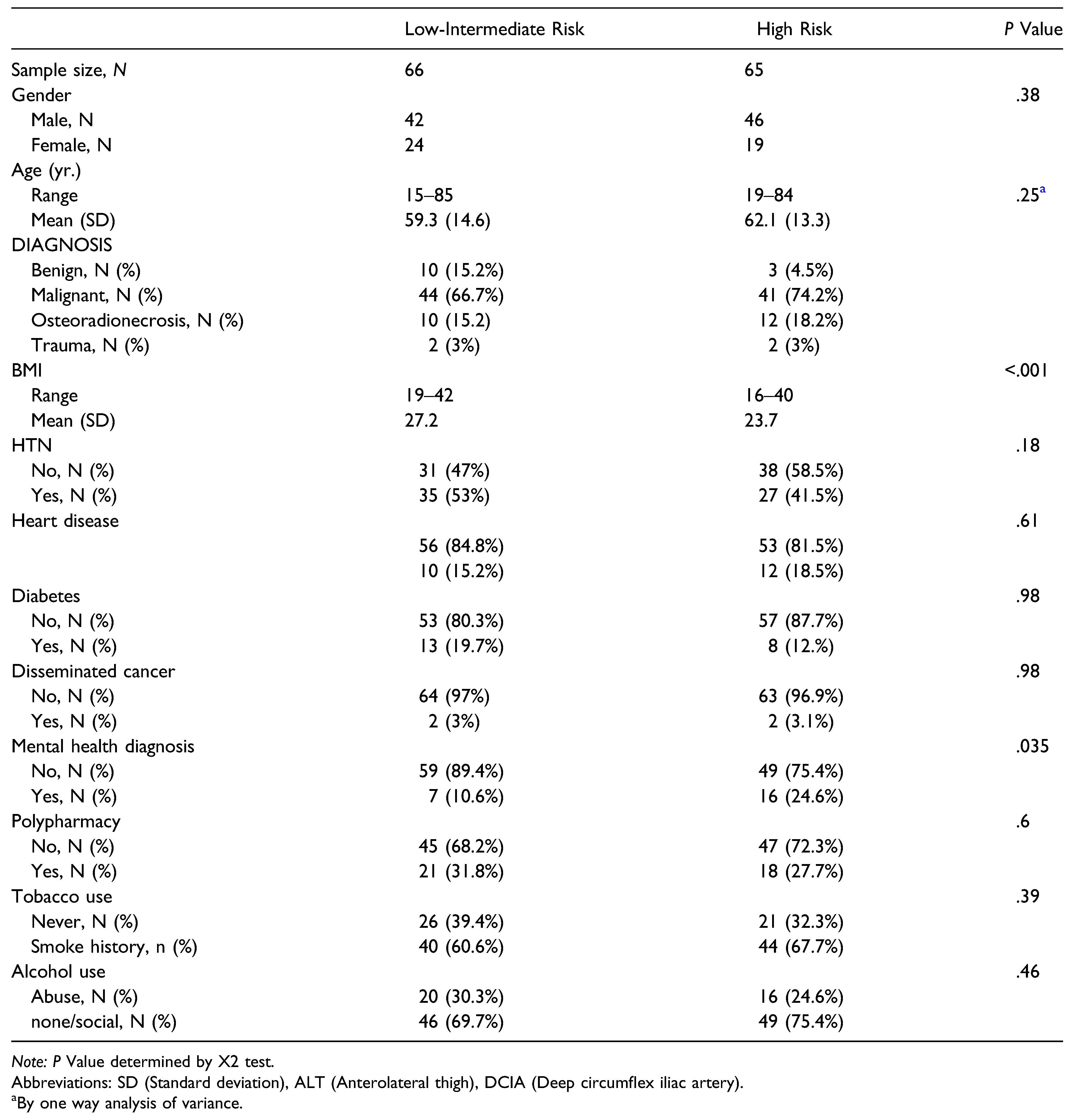

Subject’s demographic stratified by MUST score group are presented in

Table 1. A total of 131 subjects were included in the study, after classifying them with MUST. With 66 subjects on the low-intermediate risk group, and 65 subjects on the high-risk groups. Subjects in both groups were roughly similar in age and gender distribution. The high-risk group had more malignant pathology cases (74.2%) than the lowintermediate risk group (66.7%); however, there was no statistically significant difference (

P = .23). Both groups were roughly homogeneous with no statistically significant difference in history of Hypertension, Diabetes, mental health diagnosis, lung disease, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, chemotherapy, and radiation to the head and neck, the high risk group had more subjects with mental health diagnosis (24.6%) than the low-intermediate group (10.6%), this was statistically significant (

P = .03), however, in the multivariate analysis it was not related with primary or secondary outcomes. There was statistically significant difference in mean BMI (<.001), with patients in the high-risk group having a mean BMI of 23.7 kg/m

2, vs. The lower-intermediate group with BMI 27.2 kg/m

2.

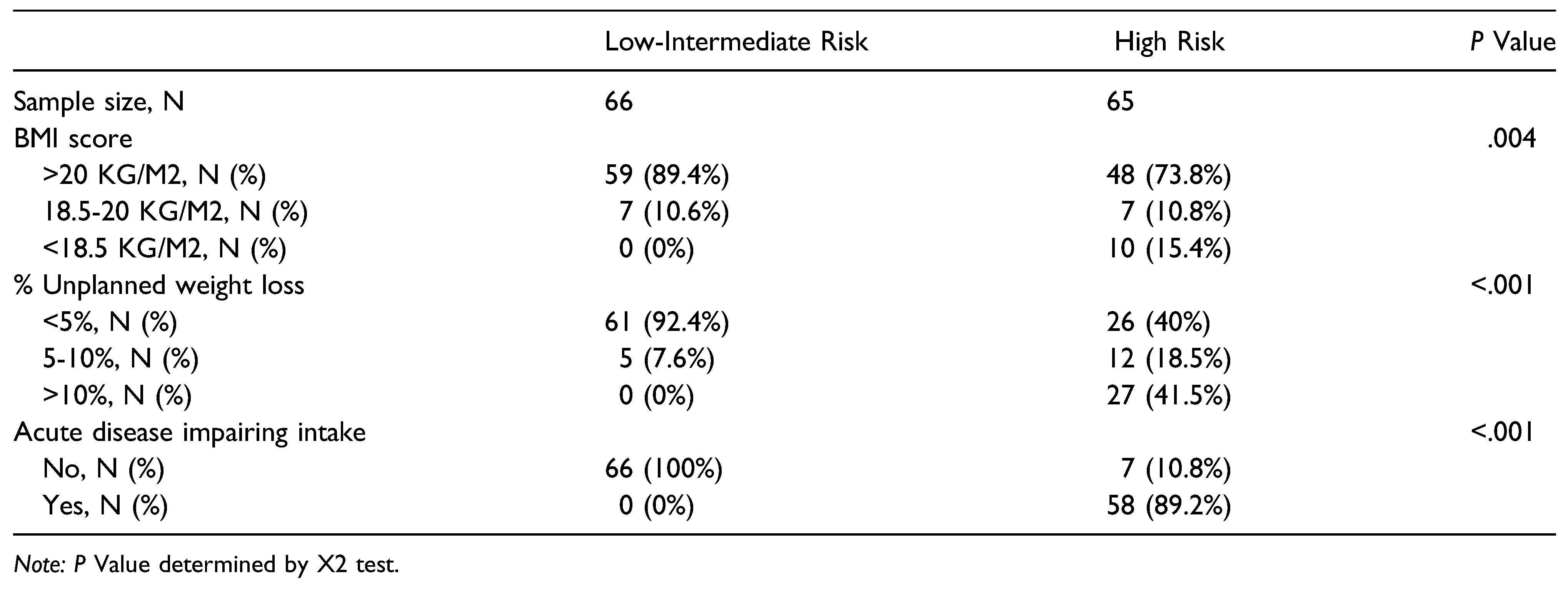

The analysis by group of the scoring items for MUST are presented in

Table 2. The Low-Intermediate risk group had 15.6% more subjects with BMI >20 kg/m

2 than the High-risk group (

P = .02), both groups had the same number of subjects with BMI between 18.5 kg/m

2 and 20 kg/m

2 and the High-Risk group had 15.4% subjects with BMI <18.5 kg/m

2 while the Low-intermediate group had no subjects (

P = .001).

Most of the subjects in the Low-Intermediate risk group (92.4%) had an unplanned weight loss (<5% of their BMI) in the last 3–6 months, while 41.5% of the subjects in the High-risk group had an unplanned weight loss >10% (P ≤ .001).

None of the subjects in the Low-Intermediate risk group presented with acute illness impairing nutritional intake for 5 days, compared to 89.2% of the subjects in the High-risk group (P ≤ .001).

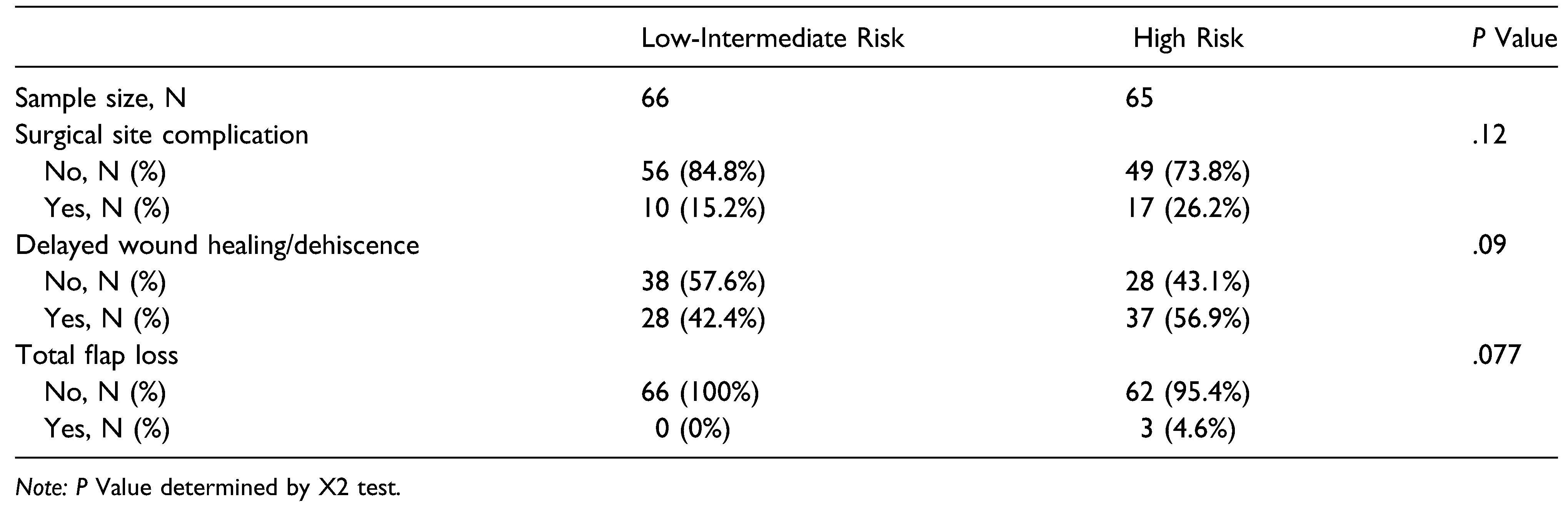

The complication percentage between groups are presented in

Table 3. The patients classified in High-risk group according to the MUST score had 11% more surgical site complications (

P = .120) and 13.7% more delayed wound healing and dehiscence (

P = .09); only 3 subjects in the study presented total flap loss and they were all in the Highrisk group, however, these results were not statistically significant (

P = .07).

Multivariate analysis showed that total flap loss (n = 3), and partial flap loss (n = 3) were not related to any specific comorbidity or medical history, only 1 of the lost flaps was on a subject with history of radiation to head and neck (P = .9), and all the 3 total flap loss were in non-diabetic subjects. Only 1 out of 3 partial loss flap was on a subject with diabetes (P = .09) and none was in subjects with history of radiation.

Surgical site complication and delayed wound healing rates were not increased by any specific medical comorbidity or history such as radiation or chemotherapy.

The independent analysis of the MUST variables 0 showed that all the total flap loss (P = .04), higher surgical site complication rate (P = .02) and were associated with subjects with acute illness impairing nutritional intake.

Discussion and Conclusion

Malnutrition has been found to have negative effects on the immune system and inflammatory responses, impairing the wound healing process [

1], and has been well established to be a poor prognostic indicator in both medical and surgical patients. Substantial efforts have been made to identify patients at risk of malnutrition and early intervention with nutritional supplementation might decrease risk of complications [

12]. Aside from benign pathology and trauma patients undergoing head and neck reconstruction, malnutrition is most prevalent in patients with malignancies of the head and neck [

13].

MUST is a five-step nutritional screening tool to identify patients who are malnourished and at risk of malnutrition [

10]. Three independent criteria are used by MUST to determine the overall risk for malnutrition: current weight status using BMI, unintentional weight loss, and acute disease effect that has induced a phase of nil per of >5 days. Each parameter is rated as 0, 1, or 2. Overall risk for malnutrition is established as low (Score = 0), Medium (score = 1), or high (score ≥2). Each of these criteria can independently predict a clinical outcome, but together the three criteria are better predictors than each by itself [

6,

10].

The result of this study shows that the subjects with a MUST score ≥2 who undergo head and neck reconstruction with free tissue transfer are more susceptible to present surgical site complications, delayed wound healing and dehiscence. The frequency of complications in the Low-intermediate risk and the High-risk groups were 15.2% and 26.2%, respectively, and the frequency of delayed wound healing in the Low-intermediate risk and the High-risk groups were 42.4% and 56.9%, respectively, and subjects with acute disease effect that induces a phase of nil per os for >5 day have higher risk of total flap loss and surgical site complication.

These findings mirror results noted in several retrospective analysis [

4,

5,

10,

14,

15].

Although the values of the overall MUST Score are not statistically significant, the analysis of the MUST independent variables show that the results of this study are clinically significant suggesting MUST as an effective preoperative nutritional assessment tool to predict postoperative healing complications.

Nutritional screening is the first step in identifying subjects who may be at nutritional risk or potentially at risk, and who may benefit from appropriate nutritional intervention, the subjects identified to be at risk can be adequately treated with oral nutritional supplements and subjects who are unable to meet their nutritional requirements orally may require nutritional support with enteral or parenteral nutrition. The early consult to nutritionist team can help to identify these subjects at risk and optimize preoperatively the patients undergoing head and neck reconstruction.

In this study, all subjects underwent nutritional assessment and early intervention by nutritionist team during the post-operative time. These interventions (oral nutritional supplementation, caloric supplementation with balanced essential amino-acid mixture given between meals) varied depending on the nutritional requirement of each subject.

The findings of this study may contribute to all the factors involved in the success of microvascular reconstruction of the head and neck.

Subjects classified preoperatively as at high risk for malnutrition specially the ones with acute illness impairing nutritional intake can benefit from additional preoperative procedures to enhance nutritional supplementation. (e.g., gastric feeding tube placement)

Further investigation should evaluate the response between patients receiving preoperative enhanced nutritional supplementation and free flap survival based on the MUST results