Introduction

Mandible fractures are common traumatic injuries [

1,

2,

3,

4], accounting for 36–70% of all facial fractures [

3]. These injuries are most frequently caused by physical violence and often occur in men in the second and third decades of life [

1,

4,

5,

6,

7]. When improperly managed or left untreated, fractures of the mandible can lead to chronic pain, significant malocclusion, and infections [

2,

8].

The objective of treatment for mandibular fractures is restoration of premorbid occlusion in order to regain masticatory function. Management options for mandibular fractures include non-operative management, closed reduction with maxillomandibular fixation (MMF), and open surgical fixation [

2,

5,

8,

9]. Non-operative management such as prescribing a soft, no-chew diet is appropriate for compliant patients with nondisplaced fractures, unchanged occlusion, and extensive occlusal contact [

9]. Closed reduction with MMF is employed as a method of intervention for patients with minimally displaced or grossly comminuted fractures, atrophic mandibles, or fractures of the coronoid or condyle [

8]. Finally, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of the mandible is achieved through the use of rigid plating systems or lag screws and is frequently offered in situations where fractures are significantly displaced [

8].

In the United States, patients with fractures of the mandible are evaluated and treated by plastic surgeons, otolaryngologists, and oral surgeons. Because definitive management is performed by surgical subspecialties, patients who present to facilities without these particular services are often transferred to tertiary care centers specifically for evaluation by facial trauma specialists. However, the majority of patients do not receive definitive treatment for their fracture on the day of injury [

10,

11,

12], with an average time to repair of approximately 5–7 days [

3,

11]. Indeed, no correlation between timing of intervention and rate of complications has been shown in the literature [

2,

3,

7,

8,

10]. Further, the acute evaluation and management of mandibular fractures can be resource intensive for the patient, the hospitals involved, and the health care system at large. Given the continued rise of healthcare costs in the United States, it is important to identify areas of potential cost savings while still providing efficient, safe, and high-quality care to patients [

6].

The purpose of this retrospective study is to assess the initial evaluation and management of patients with mandible fractures in order to better characterize current practices regarding the acute care of this patient population. We hypothesize that, at our institution, a high proportion of patients transferred from outside hospitals for mandibular fractures are evaluated and subsequently discharged from the emergency department (ED) with no acute intervention. We aim to identify, characterize, and quantify this population and evaluate the incidence of discharge directly from the ED without procedural intervention.

Methods

After Institutional Review Board approval, a retrospective chart review was conducted of all patients who presented to the emergency department with fractures of the mandible between January 1, 2017 and May 1, 2020. Patients were identified in the trauma consult list of the plastic and reconstructive surgery service, which evaluates and treats the majority of such injuries at our institution. Subjects included in this study were those who presented to our emergency department within seven days of an isolated fracture of the mandible and were subsequently evaluated in the ED by plastic surgery. Exclusion criteria included multiple injuries, history of prior mandibular fractures, and presentation greater than seven days from injury. Each medical record was reviewed by the authors. Relevant data including patient age, gender, mechanism of injury, laterality of fracture (ie left, right, midline or bilateral), type of presentation (ie, primary or transfer), treatment plan, time to treatment, and patient outcomes were recorded. The primary outcome was defined as discharge directly from the emergency department vs intervention or admission upon presentation. Administration of antibiotics or other medications as well as prescription of a soft diet were not included as interventions during the review.

Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software hosted at the hospital’s Department of Information Services. REDCap (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) is a secure, webbased NIH-supported software platform designed for data capture and analysis. Variables were summarized using descriptive statistics. The relationship with initial disposition was assessed via tests of association, including Student’s t-test, Fisher’s exact test, or chi-square tests. Significance was set to P values less than .05. Multivariate regression analysis was conducted to determine predictors of presentation to outside hospital followed by transfer to our institution. All analyses were conducted in R version 4.03 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

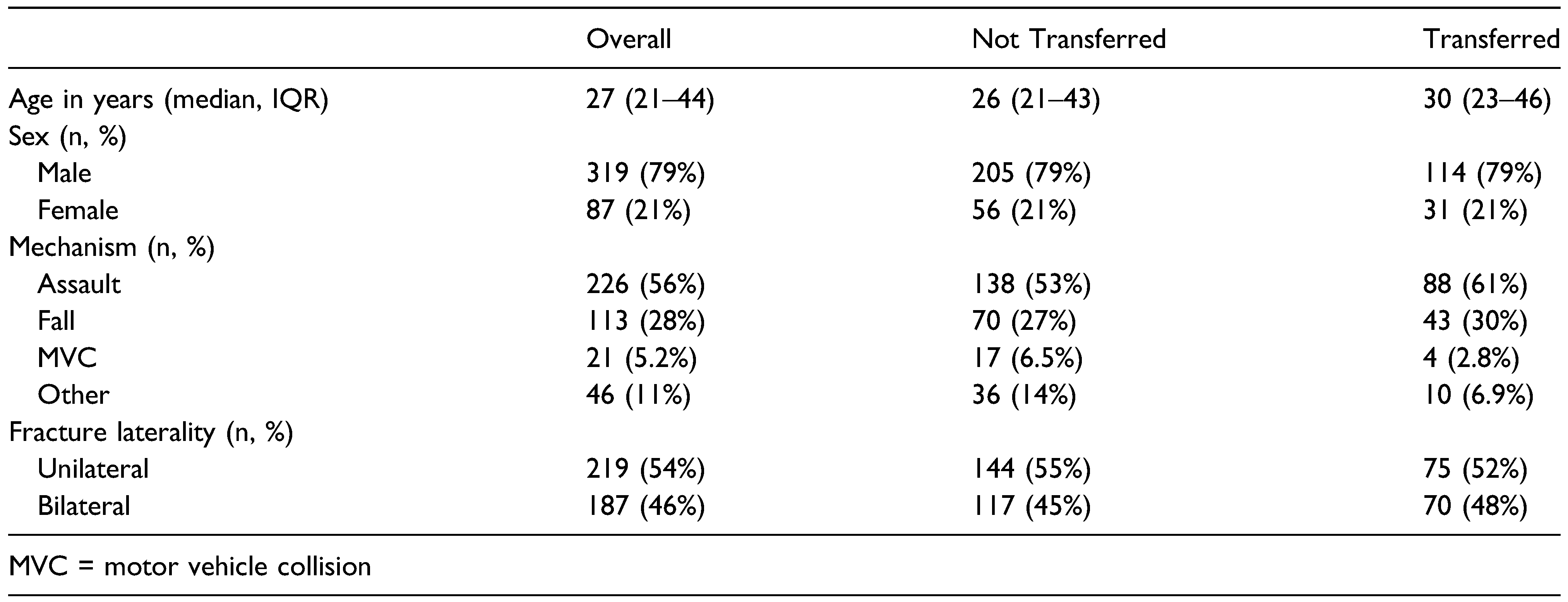

A total of 406 patients presented with isolated mandibular fractures between January 2017 and May 2020 and met inclusion criteria. The average age at the time of injury was 32 ± 14 years for men and 40 ± 24 years for women. Men were predominantly injured (319 total patients) with a maleto-female ratio of 3.6:1. The most common mechanisms of injury were assault (56%), fall (28%), and motor vehicle collision (5.2%) (

Table 1).

Twenty-three patients were admitted to the plastic surgery service and received operative management for their injuries during admission, eight of whom were transferred from outside hospitals. Of these 23 individuals, seven (30.4%) were admitted primarily for pain control, which could likely have been managed at the outside hospital and provided with outpatient follow-up. The remaining most common reasons for admission included pediatric injuries (six patients, 26.1%), social issues (six patients, 26.1%), and grossly open fractures (four patients, 9.1%). Ultimately, 270 (66%) of all patients underwent operative intervention as the definitive management for their mandibular fractures. There was an average of 4.86 ± 3.70 days between date of presentation and date of surgical intervention across all patients. There was no statistically significant difference in time to intervention between those patients who presented primarily to our institution (4.71 ± 3.5 days) vs those who were transferred for specialty evaluation (5.15 ± 4.05 days) with a P value of .3629. Between patients who presented primarily and those who were transferred from an outside hospital, there was found to be no statistically significant difference in the need to undergo some form of intervention to fixate their fracture, defined as either MMF or ORIF (P = .947).

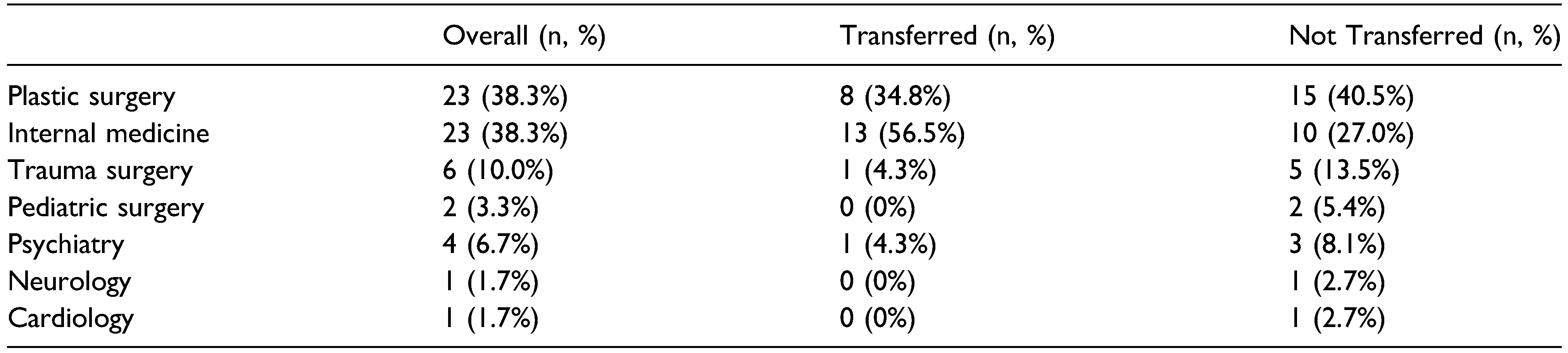

In total, 145 patients (36%) were transferred from outside hospitals. Only one of these patients required immediate intervention (ie, on the day of evaluation), this patient underwent bridling of a symphyseal fracture in the Emergency Department for comfort. Of these patients, 122 (84%) were discharged from the emergency department, while the remaining 23 (16%) were admitted. However, only eight (5.5%) of the transferred patients were admitted to the plastic surgery service for management of the mandible fracture, while the remaining 15 (10.3%) were deemed safe to return home by plastic surgery but were admitted to other services for management of comorbidities (

Table 2).

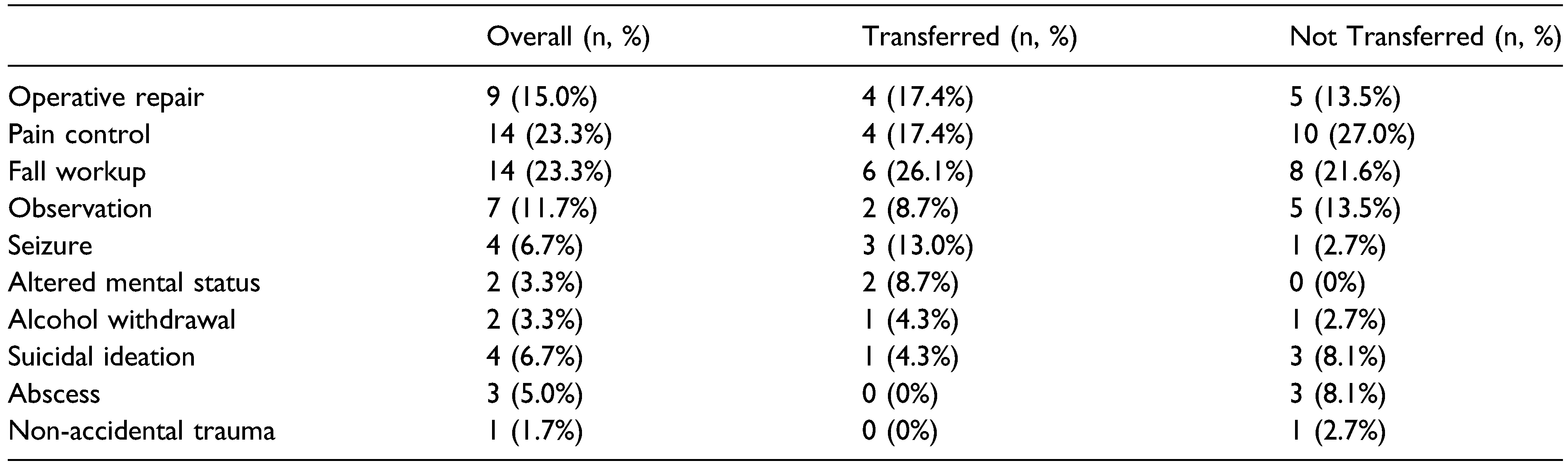

The most common reasons for admission specifically related to a mandible fracture was pain control (four patients, 17.4% of patients admitted) and operative fixation (four patients, 17.4% of patients admitted) (

Table 3). Reasons for admission for operative fixation included pediatric injuries and grossly open fractures. Pediatric patients were thought to be less able to tolerate outpatient management of their injuries due to issues with pain and oral intake. Notably, our institution is the only pediatric hospital in the state. Patients with grossly open injuries were triaged to the operating room in a more urgent fashion to obtain a thorough washout of the bony injury with mucosal closure in a more expedient fashion to reduce risk of infection.

All eight patients who were transferred and admitted directly to the plastic surgery service ultimately underwent either MMF (two patients) or ORIF (six patients). The four patients that were admitted for pain control were operated during their inpatient stay out of convenience for both patient and surgeon so as not to require the patient to return for an outpatient surgery. On the other hand, of the 15 who were transferred and admitted to other services, 11 patients (73%) underwent non-operative management, while only one (7%) and three (20%) patients underwent ORIF and MMF, respectively. In summary, out of the 145 patients transferred for plastic surgery evaluation, only one patient required immediate intervention in the emergency department and only eight (5.5%) required admission to the plastic surgery service. Of those eight, only four patients were admitted specifically for operative management of their injuries. The other four were admitted for pain control, which likely could have been managed at the outpatient hospital with subsequent discharge and outpatient evaluation. The average time from presentation to operative intervention in the group of patients who were transferred to our institution was 5.15 ± 4.05 days.

Overall, 261 (64%) patients presented primarily and were not transferred. Out of those, 37 (14%) were admitted, and 224 (86%) were discharged. Notably, 15 patients (40.5%) were admitted specifically for reasons related to their mandibular injuries, six (40%) and nine (60%) of whom ultimately underwent MMF and ORIF, respectively. The most common reason for admission and operative fixation was social issues (six patients, 40%), including homelessness, and need for extradition due to parole violation. The other reasons for admission and operative intervention included pediatric patients (four patients, 26.6%), pain control (three patients, 20%), and open fractures (two patients, 13.3%). The remaining 22 patients (59.5%) were admitted to other services for comorbidity management. The majority of these patients (14 patients, 63.6%) were managed non-operatively, while five (22.7%) and three (13.6%) patients underwent MMF and ORIF, respectively. In summary, a similar proportion of patients who presented to the ED with a mandible fracture were admitted, regardless of whether they were transferred or not (16% vs 14%, respectively, P = .65). Likewise, a similar proportion of patients were ultimately admitted primarily due to issues related to their mandible fracture in both groups (5.5% transferred vs 6.5% primary presentation, P = .73). The most common reasons in both groups included pediatric patients, open fractures, and social issues (ie, homelessness). Lastly, patients who were admitted to other services underwent similar treatment regardless of whether they were transferred or not (73% non-operative and 27% operative vs 65% non-operative and 35% operative, respectively, P = .60). These patients did not require transfer to our institution for management of other issues (ie, fall workup, seizures, altered mental status, etc.) which could have been easily managed at the hospital to which they presented.

Multivariate regression analysis demonstrated older age as a predictor of presentation to an outside hospital with subsequent transfer to our institution for specialty evaluation (P = .03). Sex, mechanism of injury, and laterality of fracture were not found to be predictive of presenting to an outside hospital with subsequent transfer.

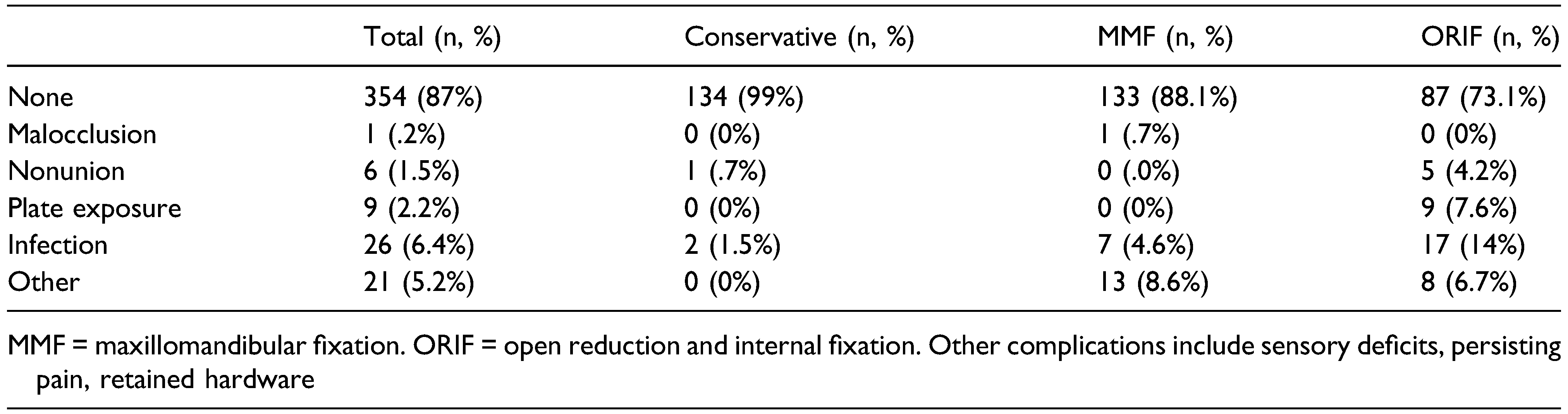

In our study, 52 patients (13%) experienced some form of complication as a result of their injury and treatment (

Table 4). Of these patients, 36 (69.2%) presented primarily to our institution, whereas 16 (30.8%) were transferred. There was no significant difference in terms of complications between patients who were transferred and those who presented primarily (P = .520).

There was a statistically significant difference in rates of complications between the types of interventions, defined as non-operative, maxillomandibular fixation, and/or open reduction and internal fixation (P < .001). Of the 52 patients who experienced a complication in their care, 18 (34.6%) underwent MMF as the definitive treatment for their mandibular fractures, whereas 32 patients (61.5%) underwent ORIF. The patients who experienced a complication were more likely to have undergone MMF or ORIF as opposed to non-operative management, with an odds ratio of 9.2 (95% CI: 2.6–58.7; P = .003) for MMF and 25.8 (95% CI: 7.6–162; P < .001) for ORIF.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the incidence of transfer from outside hospitals of patients with mandibular fractures for evaluation by a specialty service at our institution. We then endeavored to identify those patients who were subsequently discharged directly from the emergency department without intervention. We hypothesized that this patient population formed a significant portion of patients evaluated by the plastic surgery service at our hospital. We aimed to identify and quantify this population, as well as evaluate the incidence of discharge without intervention.

In this retrospective review of 406 patients with isolated mandible fractures, 36% of all patients were transferred from outside facilities for the sole purpose of evaluation by a subspecialist in facial injuries. Of these patients, only one required any form of procedural intervention in the emergency department. While 66% of all patients who were evaluated at our institution by the plastic surgery service required operative intervention, the majority were not treated on an emergent or urgent basis specifically for their mandible fractures with an average of 4.86 ± 3.70 days between presentation and operative management. Furthermore, while 23 transferred patients were admitted to the hospital upon transfer, only eight of these patients (1.9%) evaluated for mandible fractures were admitted to the plastic surgery service for issues related to their mandibular fracture. These issues included pain that was not well controlled, widely open fractures that necessitated more urgent intervention, and mandible fractures in pediatric patients. In our review of this patient population, these two groups of patients (pediatric patients and patients with grossly open fractures) were the only consistent groups that would seem to benefit from transfer to a tertiary care facility for specialist evaluation on the day of injury for the purpose of more urgent procedural intervention in the operating room. Upon review of those patients that presented primarily to our tertiary care center, patients experiencing homelessness or other social issues that might serve as a barrier to them returning for further care was found to be a reason for admission to the plastic surgery service for more expedient management.

In our study, we found that patients who underwent procedural intervention as the definitive form of management had statistically significant increased likelihood of complications. The more invasive treatment evaluated in our study, open reduction and internal fixation, had a higher odds ratio of complication (OR 25.83) compared to the less invasive procedural management, maxillomandibular fixation (OR 9.21).

Clinical Experience and Costs

In the United States, mandible fractures are treated as emergency conditions by emergency providers and, as a result, high costs can be incurred across the health system on multiple levels, sometimes with little benefit to the patient. The average cost for interfacility transfer and emergency department evaluation with no additional care varies by region, but in one study has been estimated to be approximately

$5900 [

13]. This amount would translate to more than

$2.3 million in costs at our hospital alone over a three-year period, or approximately

$715,000 per year.

Amid the landscape of increasingly cost-conscious medical practice, it is prudent to be critical in evaluating how common problems are triaged and treated. Treatment of mandible fractures may cost over

$2000 more (

$14,781 vs

$12,724) when the patient is transferred emergently to a hospital with a specialty consult service rather than given an outpatient referral for evaluation of their injury by a surgical specialist [

14]. In addition to the intrinsic cost associated with acute transfer of patients, outpatient treatment of mandibular fractures has been shown to be more cost-efficient (

$11,509 vs

$17,385) [

14] than repair associated with direct hospitalization after acute trauma [

15].

An important component of our study design was identification of patients with isolated fractures of the mandible, which leads to a reasonable assumption that the patients included in this study could have been initially evaluated in the outpatient setting by a specialist in facial trauma. We advocate for a system where a discussion occurs between an emergency provider and the specialty service treating mandibular fractures before a transfer is initiated. Specifically, we would recommend that patients with grossly open fractures and pediatric patients be considered for transfer to a facility with a facial trauma specialist, while other patients with mandible fractures should be triaged to evaluation in the outpatient setting. This workflow does not currently exist at our Level I trauma center, where patients are often transferred under the umbrella of traumatic injury with only cursory discussion regarding the patient’s injuries. Implementation of such a system would be a significant step towards improved stewardship of limited healthcare resources. It could also pave the way for other efforts to increase efficiency and value.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study is not without limitations. First, it can be difficult to fully evaluate the reasoning associated with the transferring physician’s decision to have the patient evaluated in a tertiary care facility from notes alone. This makes it challenging to decisively state that patients are inappropriately acutely transferred. However, we believe that this does not compromise the validity of our data. There are scenarios in which a physician may feel comfortable discharging a patient from their emergency department with outpatient follow-up with a specialty service. However, due to patient concern, a treating physician may feel obligated to have individuals evaluated in the acute setting. Finally, regional referral patterns vary widely across the country, and our results may not be congruent with treatment patterns seen by other institutions.

These findings shed light on a significant and costly gap in our acute management of facial trauma patients. Transfer of patients can be a drain of resources for hospitals, the healthcare system, and individual patients with little value-added benefit. We advocate for routine discussions between referring providers and specialty surgical services for appropriate triage of patients with acute mandibular fractures.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that transfer of patients with mandible fractures to a tertiary care center specifically for specialty evaluation on the day of injury often provides little benefit to patients and represents a significant financial burden to the healthcare system. Transfer to our institution did not result in earlier procedural intervention, and more expedient intervention subsequently did not result in decreased risk of complications. We did, however, identify two important groups of patients who would potentially benefit from more expedient specialist evaluation and procedural intervention, pediatric patients and patients with grossly open fractures.