World Health Organization (WHO) statistics indicate that 1 million people die, and between 15 and 20 million are injured annually in road traffic accidents [

9]. The cause of the injury is influenced by geographic and socioeconomic conditions, culture, religion and era which varies from nation to nation [

8,

10,

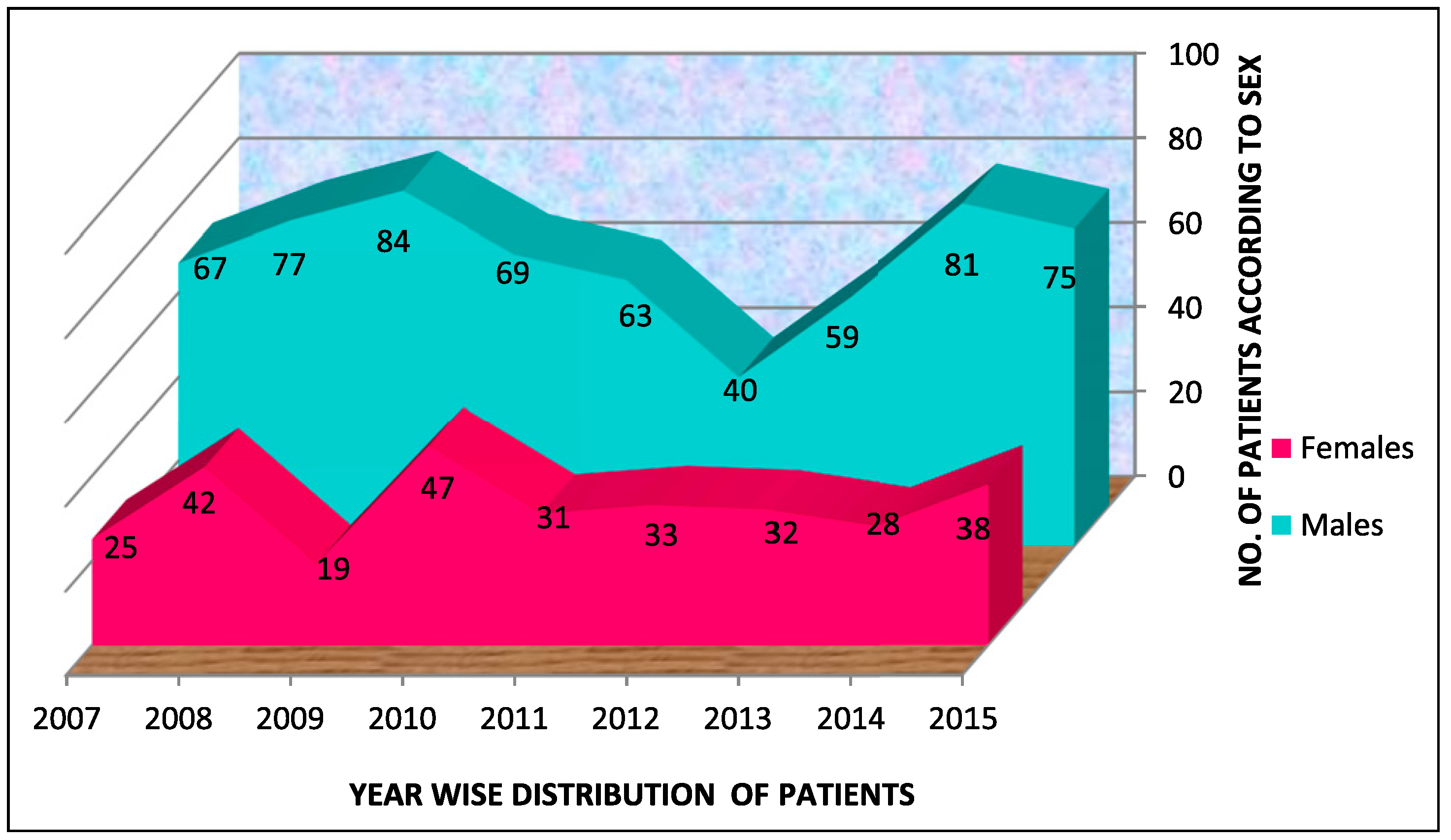

11]. The results of our investigations particularly with regard to age and gender are by enlarge in agreement with the previous reports [

12]. Males were injured commonly between the age group of 21–30 years, with a permanence of male subjects reported widely mainly due to involvement in dangerous sport activities and reckless motor vehicle driving [

8]. Although in regards to the fracture of the facial skeleton, various causative factors have been mentioned. Some studies have reported motor vehicle related accidents as the major etiology of facial fractures,[

8,

11,

13,

14,

15]. whereas others show that assault as the most frequent cause [

12,

16,

17,

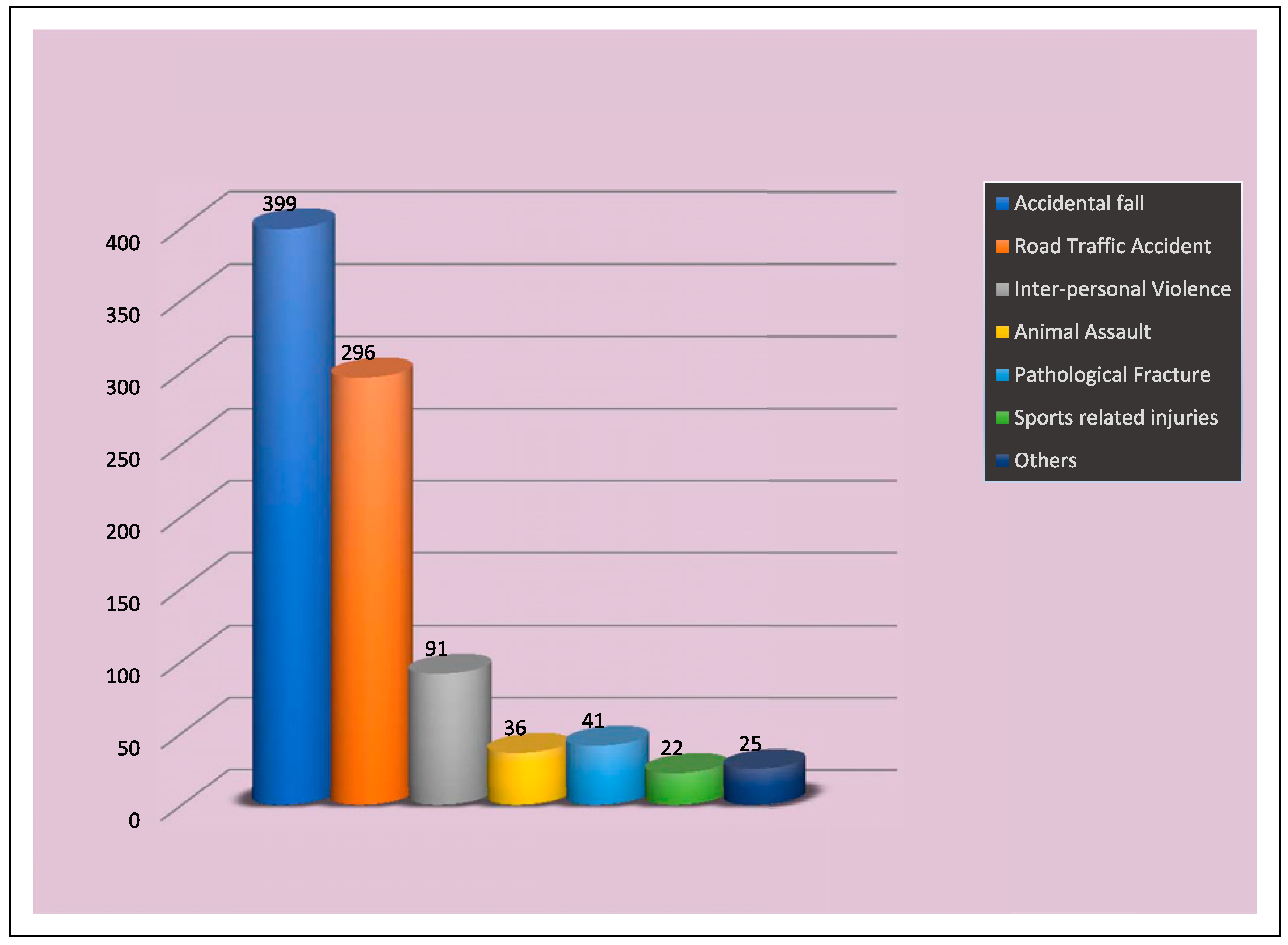

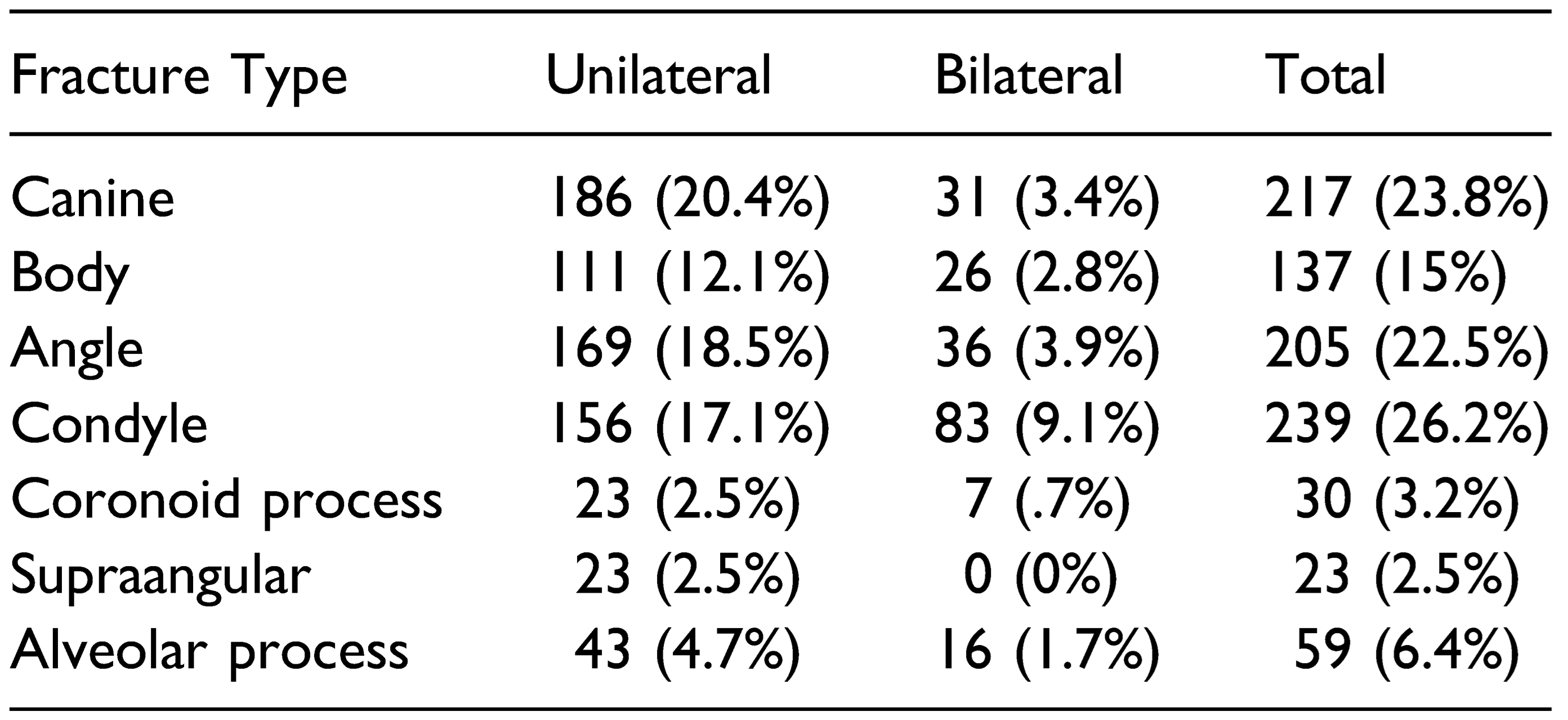

18]. The result of the present retrospective study was in stark difference to already published reports because, in our series 399 (43.8%) patients sustained mandibular fractures mainly due to fall (

Table 3,

Figure 3). This may be explained by the fact that the area of the current study is the Himalayan hilly terrain. The increased propensity to fall may be explained by the fact that motorable roads in the hilly region are scanty, especially in the rural areas, and people use temporary walking pathways to go from one place to another. These narrow non-mettle pathways on steep hills are responsible for the increased susceptibility of fall by slipping. With Himachal Pradesh being one of the most northern parts of the country with long winters, fall on the snow may explain the situation in this part of the country. The reported incidence of mandibular fractures in the literature ranges from 3 to 20% whereas already explained in our study, the incidence of mandibular fractures due to fall as high as 43.8%. Another significant etiological factor was road traffic accident consisting of 296 (32.5%) of the total mandibular fractures. In Himachal Pradesh, the factors involved are bad conditions of road, less effective law enforcement (especially for over speeding and drunk driving), increase in traffic, less use of helmets and seat belts, deep curved roads and less tolerance among youngsters, which is confirmed by the pre-eminent cause of their mandibular fractures. In the literature, fight or interpersonal violence (IPV) are reported being the most common causes of mandibular fractures in rural and farming population and in various ethnic groups [

17,

18]. Contrary to this, it is interesting that only a small percentage of the mandibular fractures were caused by I.P.V 91 (10%) in our study. The reason may be that Himachal is a small and peaceful state with low population density compared to other parts of the world. Although the fractures of the mandible have been studied vastly, studies depicting the relation between fracture site and cause are rare [

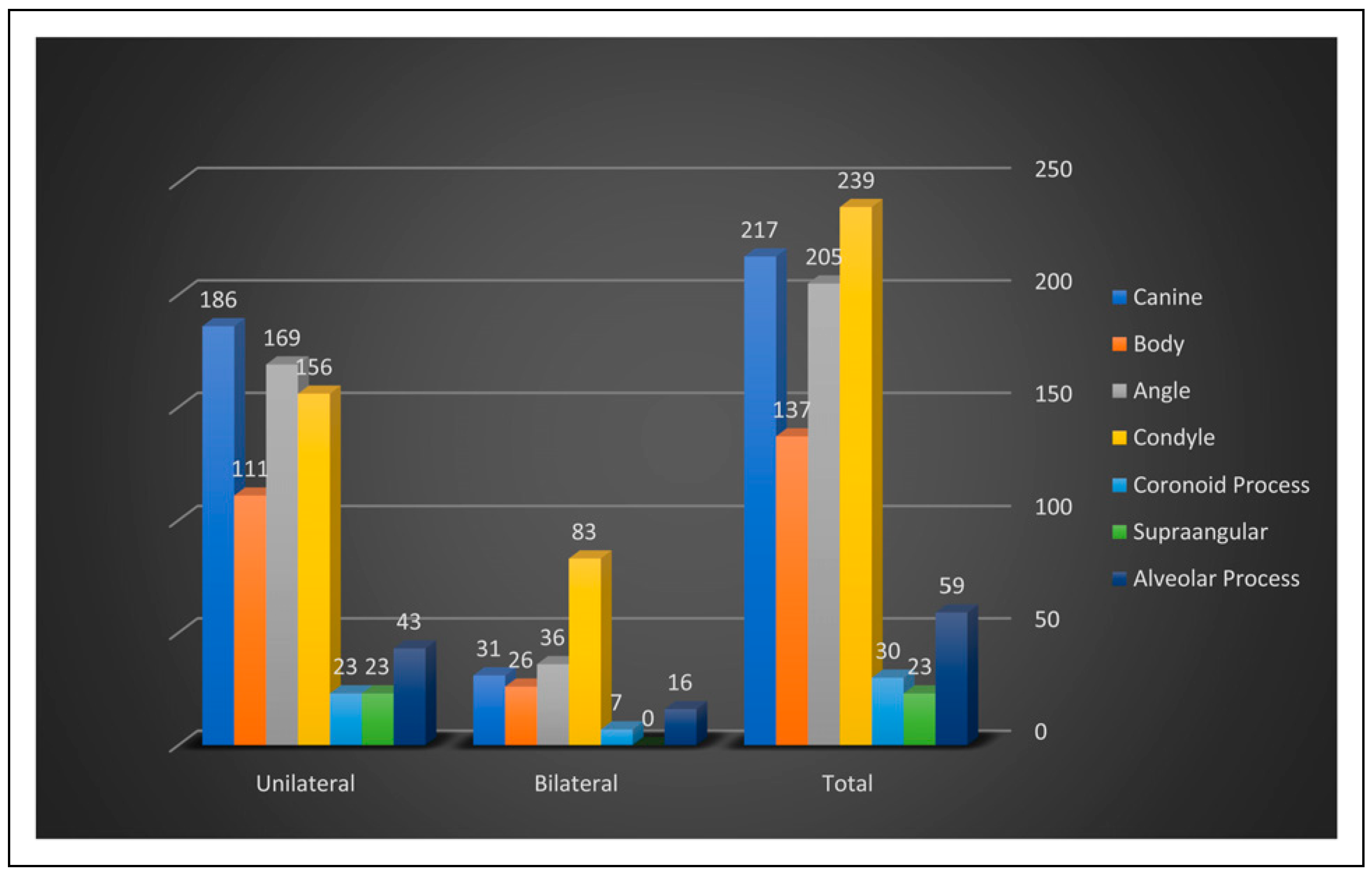

17,

19]. The location of the fracture seems to bank on the cause. The major portion of the fall-related fractures of the mandible in our study involved the condyle and canine, which are largely in agreement with the previous reports [

4,

10,

16], particularly that a fall on the chin results in a high incidence of such fractures [

20]. On the other hand, the fractures sustained in road traffic accidents (RTA) generally, were fractures of the condylar region and angle of the mandible and also include few fractures through the canine and body region which is in accordance with the finding of previous published work [

17]. In assault, there was a predominance of angle and body fracture in the present study and the least to be affected was coronoid which was consistent with the earlier reports [

21]. Sports-related mandibular fractures were common in many countries, but they were few in our series. The monthly incidence of fractures of mandible was fairly constant with seasonal variations as reported in earlier studies [

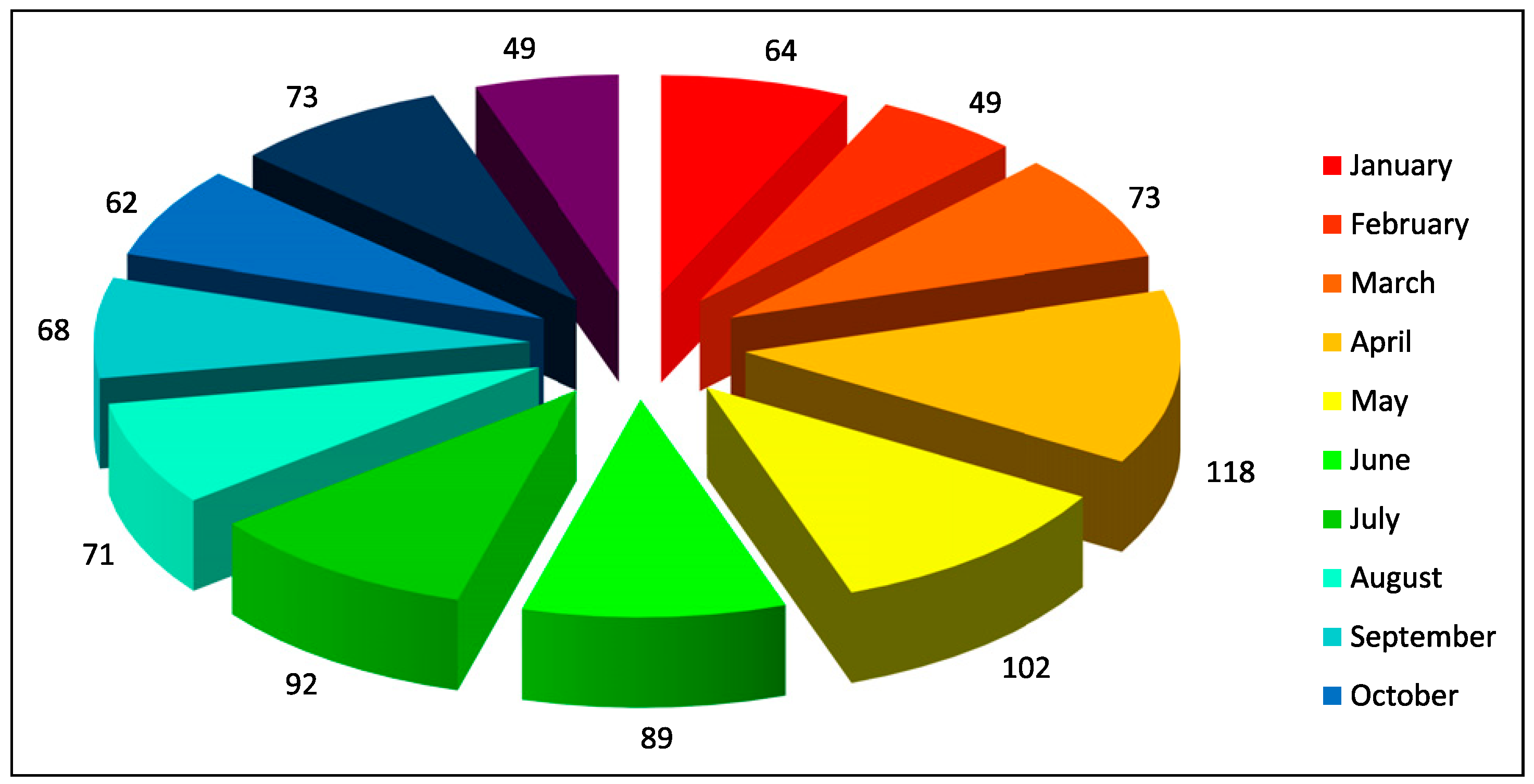

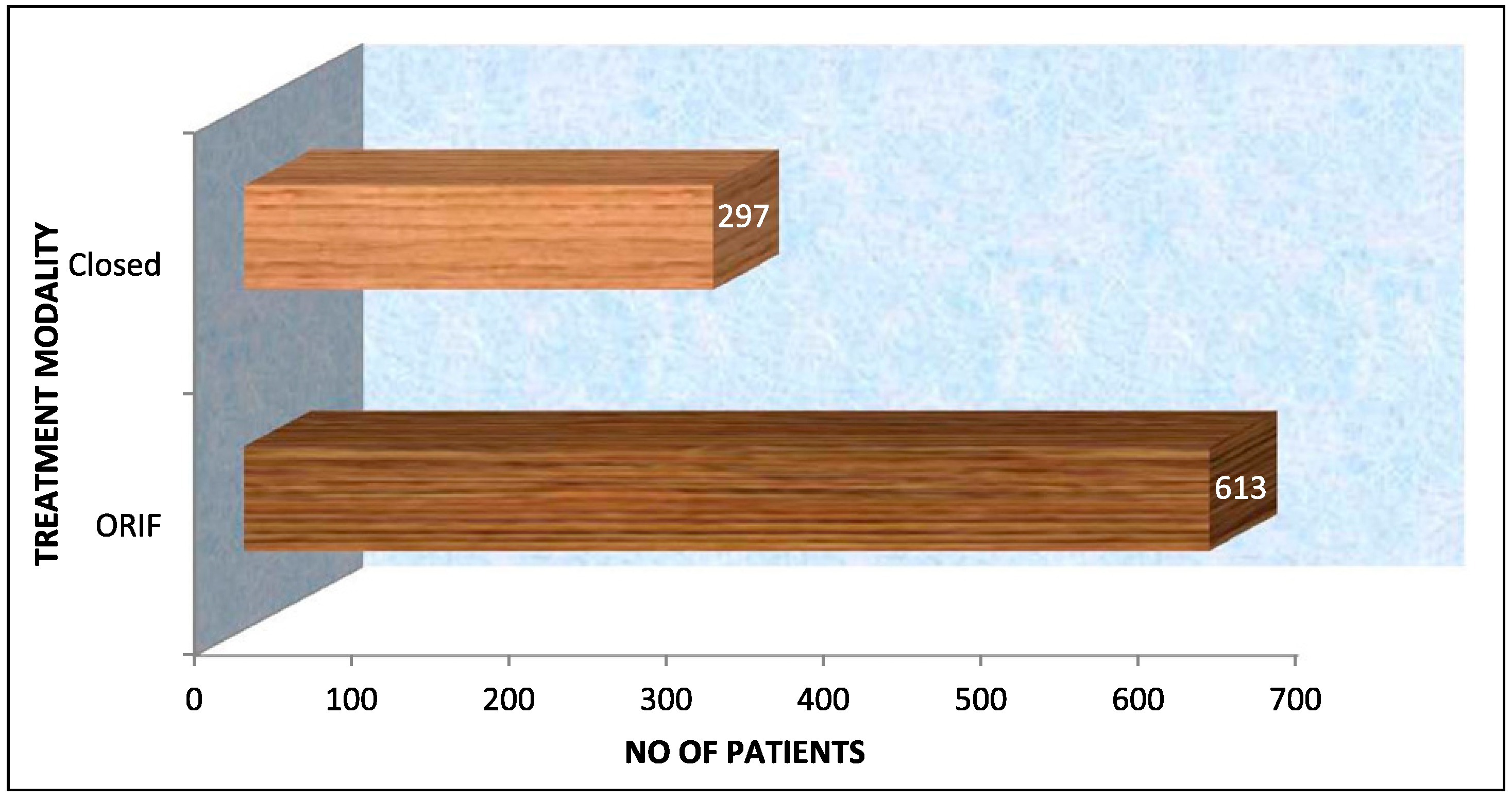

8]. The month from April to July, respectively, was the busiest in our study as in these month people from all over the country visit Himachal Pradesh because of good weather, and vacations provide an opportunity for travel and outdoor activities whilst also increasing the incidence of automobile crashes and interpersonal activities due to alcohol misuse. In recent years, there has been an inclination towards the open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) as the choice of treatment of mandibular fractures after the advent of miniplate osteosynthesis. Our choices were no different, with ORIF being the treatment of choice, in this study. The main advantage of these mini-plates is reliable, the convenience of application, rapid recovery of normal jaw function and maintenance of normal body weight [

22].