Abstract

Study Design: The investigators designed and implemented a 20-year cross-sectional study using the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database. Objective: The purpose of this study is to estimate and compare hospital admission (danger) rates between rugby and football of those who presented to the emergency department with head and neck injuries after playing these sports. Methods: The primary predictor variable was sport played. The primary outcome variable was danger, measured by hospital admission rates. Results: Over the past 20 years, there has been a trend of decreasing incidence of injuries presenting to the emergency department in both sports. There was no difference in the rate of hospital admission when comparing football and rugby (OR, 1.2; P = .1). Male gender was associated with an increased risk of admission. Other variables associated with hospital admission included white racial group, injury taking place in the fall, being either young (15–24 years old) or senior (65 years of age and over), and being injured at school or at a sport/recreational facility. Conclusions: There is no difference in danger as measured by admission rates between American football and rugby. There exists, however, several variables that are associated with admission when sustaining injury to the head and neck, when playing these two sports.

Introduction

American football and rugby are both considered full contact sports, with the possibility of serious bodily injury, in particular to the head and neck. American football is played by two teams with 11 players on the field at a time, with the ultimate objective of earning team points by moving an oval leather football into the opposing teams’ endzone [1]. American football is played in a full contact manner, meaning the athletes purposefully hit or collide with one another, in nearly all leagues and age groups [1]. The main equipment used in American football is the helmet, which consists of a hard plastic shell and facemask, and shoulder pads with shock-absorbing foam. Other equipment consists of mouthguards, thigh pads, knee pads, and chest protectors and padded pants [1]. American football is a fastpaced physical game that at its core is composed of high velocity collisions, with the potential for severe injury.

Rugby is one of the most played sports worldwide and is quickly gaining popularity in the United States among college and youth athletes. Rugby consists of 15 players per team [2]. The objective of rugby is to move the oval rugby ball across the field into the other opponents’ tryzone which awards the team points. There is very little personal protective equipment in rugby. Players may elect to wear optional padded head coverings, mouthguards, or chest protection [2]. Rugby is played in a continuous manner with very little stoppage of play and, similarly to American football, is very fast paced with high velocity collisions and potential for severe injury.

The purpose of this study is to answer the following clinical question, “In those subjects who play rugby or American football, is playing rugby, when compared to American football, more likely to lead to hospital admission (danger)?” Player oriented variables including demographic (age, gender, and race) and injury-oriented variables (body part and diagnosis) were also investigated in regards to hospital admission rates. The authors hypothesize that either sport is not more dangerous than the other. The aim of this study is to estimate and compare the frequencies, types, and hospital admission rates of head and neck injuries in subjects who play rugby and American football. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to directly compare head and neck trauma among rugby and American football players.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The investigators designed and implemented a 20-year cross-sectional study. The study was conducted using the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS), which is maintained by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). The NEISS acquires data from a cohort of 100 hospitals with 24-hour emergency departments (EDs) containing at least six beds in the United States. This dataset is publicly available and contains detailed reports of injuries from consumer products or sports and recreational activities.

Study Sample

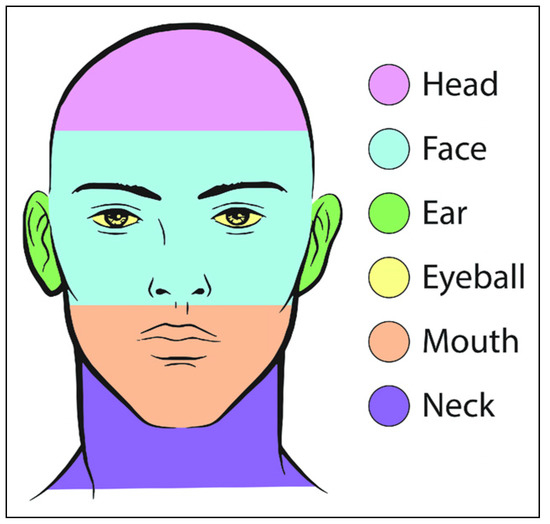

The study sample was derived from the population of patients who presented to 24-hour EDs for evaluation and management of their injuries related to playing rugby or football from January 1, 2000 through December 31, 2019. Using the NEISS database, entries categorized under the codes 3234 (rugby; activity/apparel/equipment) and 1211 (football; activity/apparel/equipment) were included in this study. Subjects eligible for study inclusion had sustained injuries that occurred secondary to the circumstances surrounding the practice of either rugby or football. Subjects were excluded from study enrollment if their injuries occurred while not playing rugby or football or if the injury did not occur in the head and neck region, which was defined using the following NEISS body part codes: 75, head; 76, face; 77, globe; 88, mouth; 94, ear; and 89, neck. Figure 1 illustrates specifically how the NEISS defined the following regions of the head and neck. The mouth entails the lips, tongue, and teeth while the face entails the eyelid area, nose, and forehead.

Figure 1.

Subregions of the head and neck as defined by the NEISS.

Study Variables

The primary independent variable was sport (rugby vs football). The primary outcome of interest was hospital admission rate. Secondary outcome variables included body part injured and diagnosis. Other variables were obtained from both patient and injury characteristics. Patient-oriented variables included demographic information (age, gender, and race). Injury-related variables included the date of injury, body part involved, diagnosis, and disposition. The diagnosis and body part codes were interpreted using guidelines provided in the NEISS coding manual. Only the most severe diagnosis was coded in each record. Emergency room disposition was grouped into either inpatient admission or non-admission.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all study variables. Bivariate analysis of patient and injury variables was performed using chi-squared and independent sample tests. A P < .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical calculations were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SPSS version 25 for Mac (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Consistent with Columbia University Irving Medical Center and University at Buffalo, research involving the analysis of de-identified data from publicly available datasets does not require institutional review board approval.

Results

Rugby Injuries

The final sample of rugby injuries included 2408 cases in total. The mean age of the patients was 21.05 years old, (range: 2.0–71.0). The vast majority of injuries occurred in players in the age range of 15–24 years old (76.5%). There was a male predilection in the gender distribution of patients, with a 4.1:1 male to female ratio. When categorized by race, white patients were the most frequent group (92.5%). The largest incidence of rugby injuries occurred during the fall season (39.5%) followed by the spring season (38.7%). The most common primary diagnosis was laceration (36.0%), followed by concussion (22.5%) and internal organ injury (20.9%). The head (50.9%) was the most frequently injured body part within the head and neck region, followed by the face (40.3%). The majority of injuries took place at sports/recreational facilities (62.9%) (Table 1).

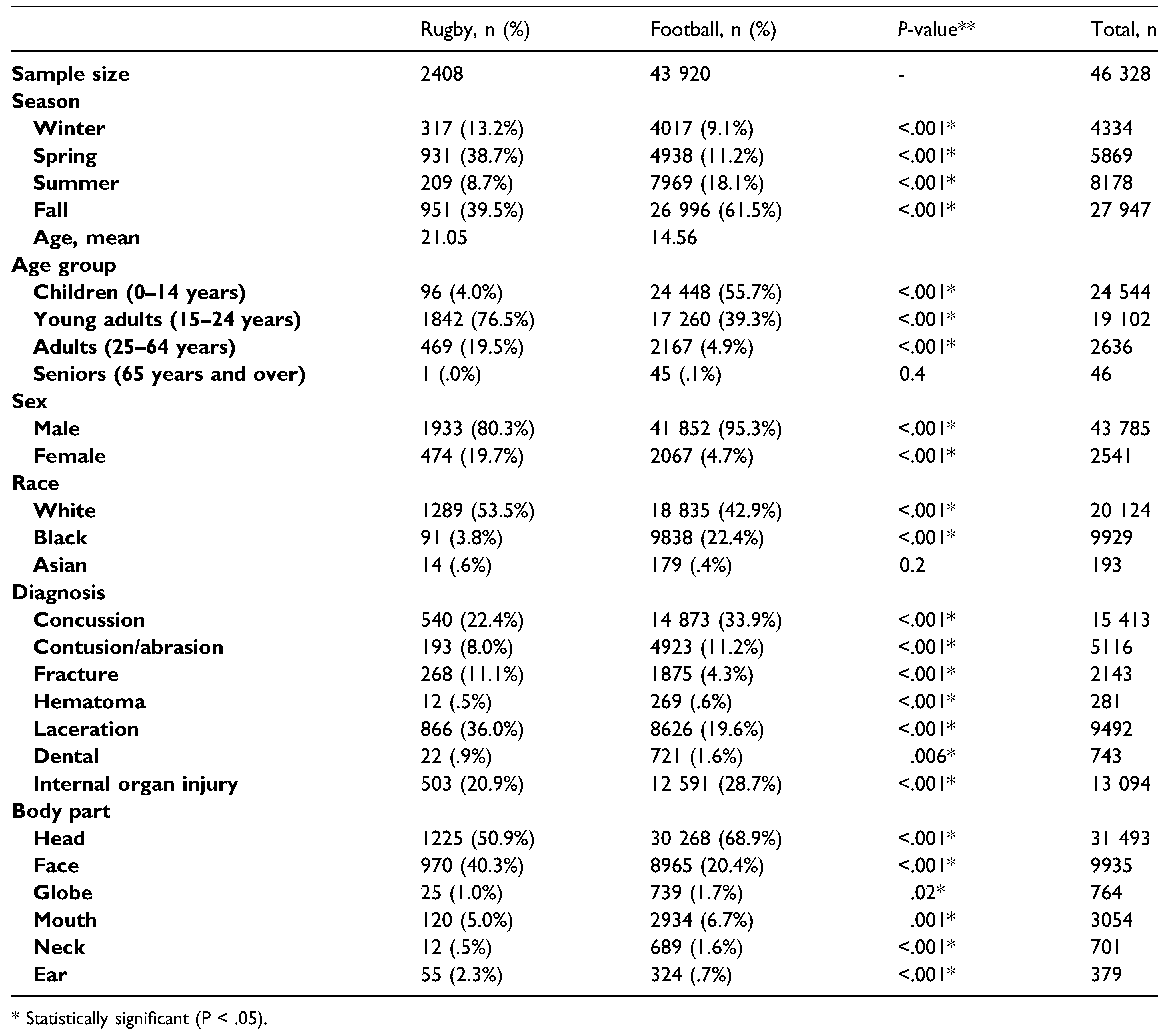

Table 1.

Patient demographics and injury characteristics stratified by rugby and football.

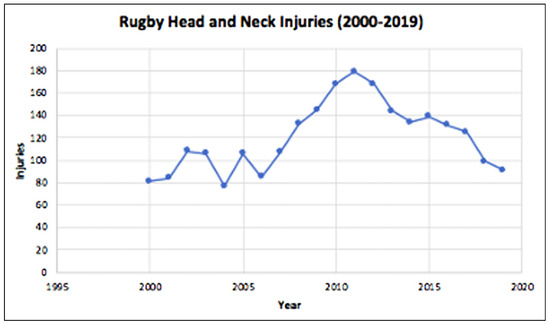

The nationally estimated incidence of rugby head- and neck-related injuries increased from 81 in the year 2000 to 91 in the year 2019; this change was not statistically significant (P = .072). The peak incidence of injuries was 171 in the year 2011 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Nationally estimated incidence of rugby players with head and neck injuries presenting to US emergency departments, 2000– 2019.

Football Injuries

The final sample of football injuries included 43 920 cases in total. The mean age of the patients was 14.56 years old, (range: 2.0–93.00). The majority of football injuries occurred in patients under 14 years of age (55.7%), while 39.3% of injuries occurred in players between the ages of 15–24. There was a severe male predilection in the gender distribution of patients, with a 20.2:1 male to female ratio reported. 42.9% of all football injuries occurred in players of white race followed by African American players who exhibited 22.4% of the injuries. The largest incidence of football injuries occurred during the fall season (61.5%). The most common primary diagnosis was concussion (33.9%) followed by internal organ injury (28.7%) and laceration (19.6%). The head (68.9%) was the most frequently injured body part within the head and neck region, followed by the face (20.4%) (Table 1).

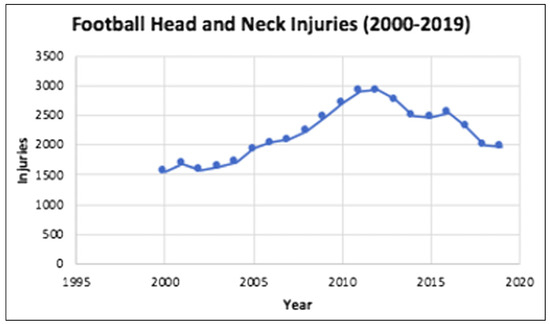

The nationally estimated incidence of American football head- and neck-related injuries increased from 1553 in the year 2000 to 1971 in the year 2019; this change was statistically significant (P = .005). The peak incidence of injuries was 2928 in the year 2012 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Nationally estimated incidence of American football players with head and neck injuries presenting to US emergency departments, 2000–2019.

Rugby vs Football Injuries

The demographic and injury comparisons between the two sports (rugby vs American football) are presented in Table 1. Relative to rugby injuries, American football injuries occurred more frequently in male individuals (95.3% vs 80.3%; P < .01) who were less likely to be white (42.9% vs 53.6%; P < .01) and more likely to be black (22.4% vs 3.8%; P < .01). Furthermore, rugby injuries were more likely to occur during the winter (13.2% vs 9.1%; P < .01) and spring (38.7% vs 11.2%; P < .01) seasons and less likely to occur during the summer (8.7% vs 18.1%; P < .01) and fall (39.5% vs 61.4%; P < .01) seasons.

A greater proportion of American football injuries involved the head (68.9% vs 50.9%; P < .01), neck (1.6% vs .5%; P < .01), globe (1.7% vs 1.0%; P < .01), and mouth (6.7% vs 5.0%; P < .01) and resulted in concussions (33.9% vs 22.4%; P < .01), internal organ injuries (28.7% vs 20.9%; P < .01), contusions/ abrasions (11.2% vs 8.0%; P < .01), and dental injuries (1.6% vs .9%; P < .01). However, a greater proportion of rugby injuries involved the face (40.3% vs 20.4%; P < .01) and ear (2.3% vs .7%; P < .01) and resulted in fractures (11.1% vs 4.3%; P < .01) and lacerations (36.0% vs 19.6%; P < .01). Finally, rugby injuries were more likely to occur in young adults (76.5% vs 39.3%; P < .01) and adults (19.5% vs 4.9%; P < .01) but less likely to occur in children (4.0% vs 55.7%; P < .01) relative to football injuries (Table 1).

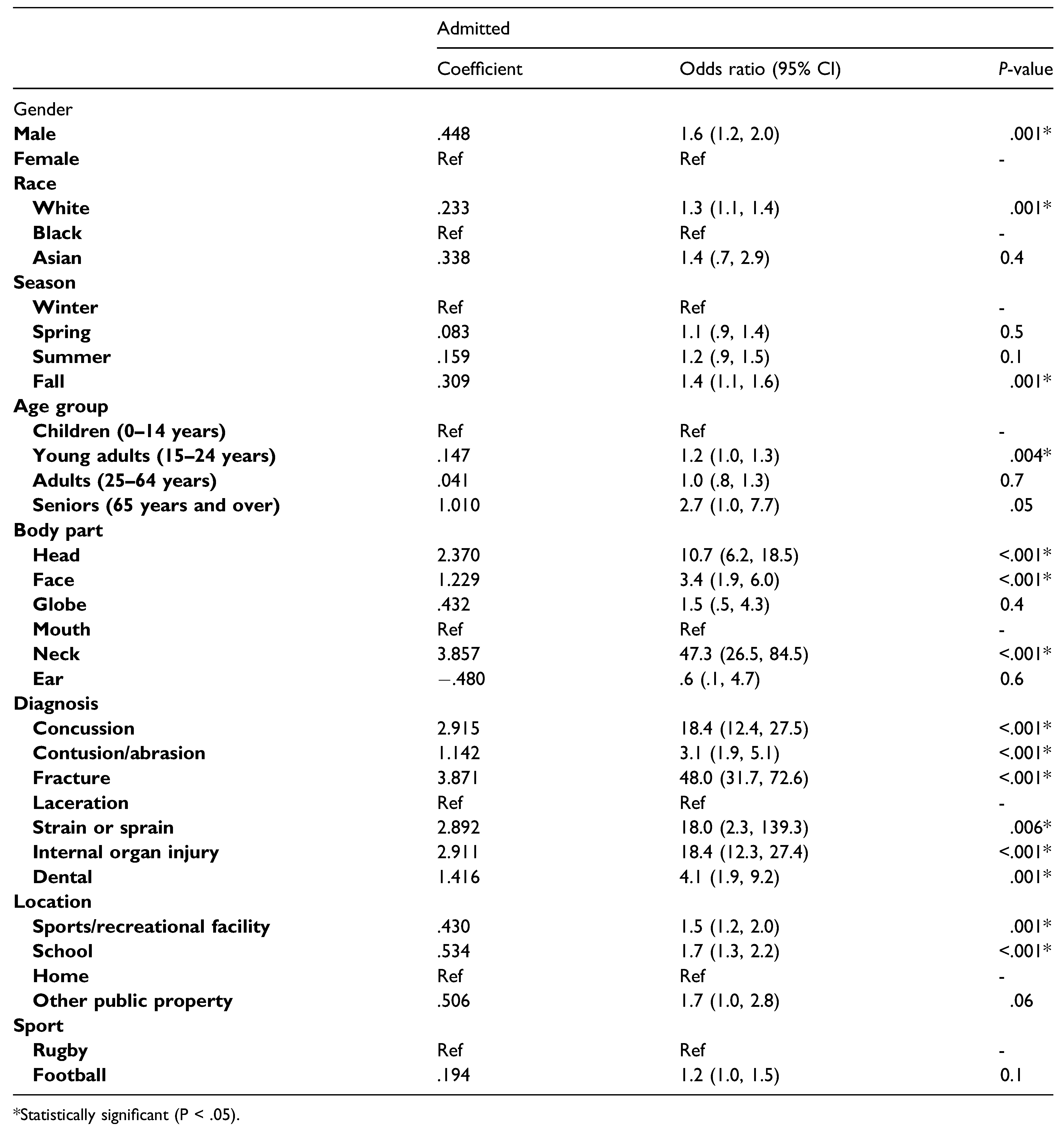

Results of the univariate logistic regression model are reported in Table 2. Relative to females, males were associated with 1.6-fold odds of admission (P < .01). Relative to black players, white players were associated with 1.3-fold odds of admission (P < .01). Relative to the winter season, fall admission rates were associated with 1.4-fold odds of admission (P < .01). Other variables significant in the univariate analysis included age, injury location, injuries with lacerations vs concussions, and among others (Table 2). Relative to rugby, American football was not associated with an increased risk of admission (P = .1).

Table 2.

Univariate logistic regression model for probability of admission.

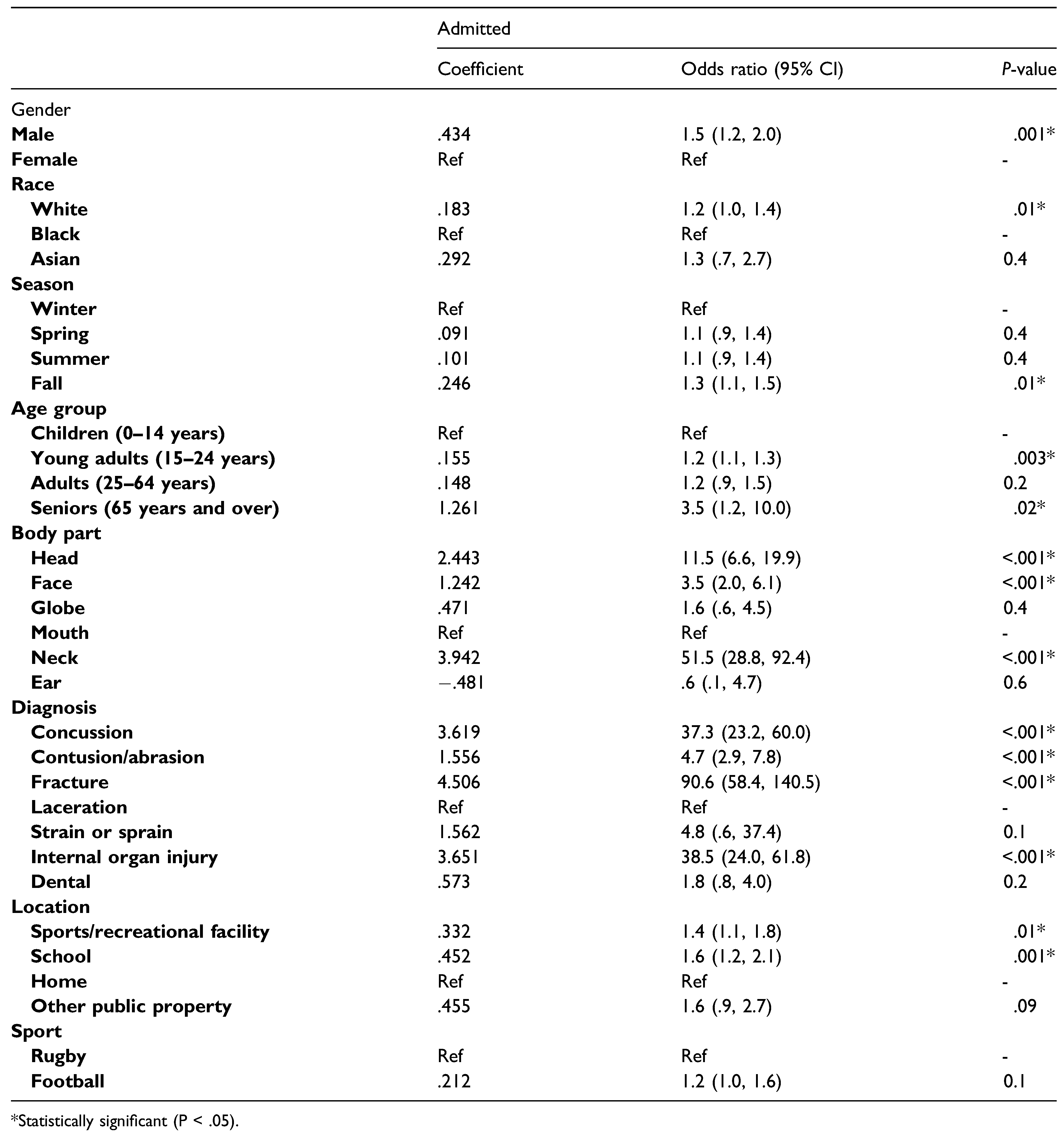

The results of the multivariate logistic regression model are reported in Table 3. There was no difference in danger (admission rate) between the two sports (OR, 1.2; 95% OR CI (1.0, 1.6); P = .1). Relative to females, males were associated with 1.5-fold odds of admission (P < .01). Relative to black players, white players were associated with 1.2-fold odds of admission (P < .01). Relative to children, young adults (OR, 1.2; 95% OR CI (1.1, 1.3); P < .01) and seniors (OR, 3.5; 95% OR CI (1.2, 10.0); P < .01) were independently associated with an increased odds of admission. Relative to the mouth, the head (OR, 11.5; 95% OR CI (6.6, 19.9); P < .01), face (OR, 3.5; 95% OR CI (2.0, 6.1); P < .01), and neck (OR, 51.5; 95% OR CI (28.8, 92.4); P < .01) were all independently associated with an increased odds of admission. Relative to lacerations, concussions (OR, 37.3; 95% OR CI (23.2, 60.0); P < .01), contusions/abrasions (OR, 4.7; 95% OR CI (2.9, 7.8); P < .01), fractures (OR, 90.6; 95% OR CI (58.4, 140.5); P < .01), and internal organ injuries (OR, 38.5; 95% OR CI (24.0, 61.8); P < .01) were all independently associated with an increased odds of admission. Relative to home, injuries which occurred at a sports/ recreational facility (OR, 1.4; 95% OR CI (1.1, 1.8); P < .01) and school (OR, 1.6; 95% OR CI (1.2, 2.1); P < .01) were independently associated with an increased odds of admission.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression model for admission between both sports.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to answer the following clinical question, “In those subjects who play rugby or American football, is playing rugby, when compared to American football, more likely to cause head and neck injuries and lead to hospital admission (danger)?” The aim of this study is to estimate and compare the frequencies, types, and hospital admission rates of head and neck injuries in subjects who play rugby and American football. After controlling for potential confounders, there was no difference in the primary outcome of danger (hospital admission) between American football and rugby.

A prospective cohort study by Willigenberg et al. in 2016 investigated injuries among American college football players and club rugby players over three seasons [3]. Overall, injury rates were 3.1 times higher in rugby compared to American football (95% CI, 2.3–4.2; P < .001). More specifically, rugby players were nearly three times more likely to sustain an injury to the head region (P = .004) [3]. This was not seen in the current study as American football players were more likely to sustain injury to the head (68.9% vs 50.9%; P < .01). As far as head and neck diagnoses go, Willigenberg et al. reported that rugby players were nearly 2.5 times more likely to sustain a concussion compared to football players (P = .027). The opposite was reported in our study as concussions were more frequently reported in American football players (33.9% vs 22.4%; P < .01). Moreover, Willigenburg et al. determined that rugby players were more likely to sustain a fracture in the head and neck region compared to football players which is consistent with our study (11.1% vs 4.3%; P < .01). It is worth mentioning that the study by Willigenberg et al. only included 201 total body injuries whereas the current study reports a much larger sample size (n = 46 328) of just head and neck injuries. In addition, the study by Willigenberg et al study included all injuries reported by team staff, whereas our study only captures patients who presented to the ED. Our data excludes injuries sustained which did not require an Emergency department visit, which may explain the varied results.

Pfister et al. [4] conducted a meta-analysis in 2016 investigating the incidence of concussions in youth sports. They reported that the three sports with the highest incidence rates of concussion were rugby, ice hockey, and American football. More importantly, they determined that rugby players were nearly eight times more likely to sustain a concussion. In the current study, concussion related injuries were more commonly seen in American football players (33.9% vs 22.4%; P < .01).

The findings in this study are not without limitations. First, this study includes data purely on patients who sought formal care at an ED. Therefore, cases of injuries handled by primary care physicians, urgent care centers, or other outpatient facilities are not included in this analysis. Hence, our analyses likely underestimate the incidence of head and neck injuries secondary to rugby or American football. Unfortunately, our study does not provide any insight into the mechanism of injury, which is a topic of interest when studying contact sports like American football and rugby. Some authors have suggested that certain tackling positions are more prone to injury [5]. A study by Sobue et al concluded that rugby tacklers with incorrect head position (i.e., in front of the ball carrier) had a higher rate of concussions and neck injuries relative to tacklers with correct head position (i.e., behind or to one side of the ball carrier) [5].

Moreover, the final sample of football injuries included 43 920 cases in total. It is important to recognize that American football injuries were more frequently reported because the NEISS is based in American and rugby is not as popular of a sport as American football in the United States. On a similar note, regarding rugby injuries, the NEISS does not specify whether the injury occurred during rugby 7s or traditional 15-a-side-rugby. In rugby 7s, each team is composed of seven players who compete over two sevenminute periods. This variant of rugby is high paced and requires different skills compared to traditional rugby. Recent research has reported that rugby 7s has a higher injury rate, which is typically more severe, causing a longer duration of missed time than traditional rugby [6]. The injury rates between the different variants of rugby are something that needs further investigation in future studies.

Conclusion

This study suggests that there is no difference in danger to the head and neck between American football and rugby as measured by hospital admission rates after presentation to an emergency department. However, injuries to the head and neck regions are more common amongst football players; the nature of these injuries is also more concerning clinically. Concussions and internal organ injuries occurred more often in football players and these types of injuries have the potential for long-term sequelae including chronic traumatic encephalopathy. It is possible that American football players have a false sense of protection due to the heavy equipment they wear. In addition, with the absence of protective padding, rugby players may adjust their tackling mechanics to be more conservative and have overall lower impact collisions compared to American football. It is important that clinicians understand these patterns of head and neck injuries as they relate to American football and rugby trauma.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

All authors viewed and agreed to the submission of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Wikipedia contributors. American Football; Wikipedia, 2021; Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_football.

- Wikipedia contributors. Rugby Union; Wikipedia, 2021; Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rugby_union.

- Willigenburg, N.W.; Borchers, J.R.; Quincy, R.; Kaeding, C.C.; Hewett, T.E. Comparison of injuries in American collegiate football and club rugby: a prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2016, 44(3), 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfister, T.; Pfister, K.; Hagel, B.; Ghali, W.A.; Ronksley, P.E. The incidence of concussion in youth sports: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015, 50(5), 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobue, S.; Kawasaki, T.; Hasegawa, Y.; et al. Tackler’s head position relative to the ball carrier is highly correlated with head and neck injuries in rugby. Br J Sports Med. 2018, 52(6), 353–358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Toohey, L.A.; Drew, M.K.; Finch, C.F.; Cook, J.L.; Fortington, L.V. A 2-year prospective study of injury epidemiology in elite Australian rugby sevens: exploration of incidence rates, severity, injury type, and subsequent injury in Men and Women. Am J Sports Med. 2019, 47(6), 1302–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2022 by the author. The Author(s) 2022.