Introduction

Mandibular fractures are a common injury in maxillofacial trauma. Approximately 25-35% of all mandibular fractures are located in the condylar region.[

1] The incidence of mandibular fractures is up to 4-times as high in men as women.[

2] A study of the US National Trauma Data Bank described assault as the major cause of mandibular fractures in men, whereas the majority of fractures in women are caused by falls and motor vehicle accidents.[

2] AOCMF defines a fracture classification by dividing the condylar process in 3 subregions: the head region, condylar neck and condylar base.[

3] Patients with unilateral mandibular condylar fractures often present with typical symptoms, including malocclusion, unilateral preauricular pain, and reduced mouth opening with chin deviation to the affected side. Cases of bilateral condylar fractures usually present with an anterior open bite with premature bilateral contact in the molar region, bilateral preauricular pain, and reduced mouth opening.[

4] The latter are often seen in association with fractures of the mandibular symphysis or parasymphysis.[

4] This combined fracture is commonly known as a parade fracture, or guardsman fracture.

The choice of treatment in condylar fractures is controversial and depends on multiple factors, such as patient age and comorbidities, presence of other mandibular or maxillofacial fractures, unilateral or bilateral fracture, level and displacement of the fracture, presence and state of dentition, dental occlusion, and the skill level of the surgeon.[

5,

6,

7] Many treatment options have been described for condylar fractures, including conservative treatment, which consists of analgesic therapy, soft diet, and physiotherapy. Other options are intermaxillary fixation (IMF) or surgery. Surgery can be endoscopic or performed as open reduction internal fixation (ORIF).[

1,

4] Although different guidelines have been described, the management of mandibular condyle fractures remains controversial.[

8,

9,

10] Kyzas et al performed a meta-analysis of studies comparing conservative management versus ORIF in patients with condyle fractures. This suggests that ORIF for condylar fractures may be as good or better than conservative management. However, the available evidence was of poor quality and not strong enough to change clinical practice.[

1]

Malocclusion is one of the major long-term complications in patients with condylar fractures.[

11] Other long-term complaints described in the literature are temporomandibular joint dysfunction, chronic pain, nerve injury, growth disorder, condylar resorption, and non-union or malunion

.[

6,

9,

11,

12,

13,

14]

Condylar fractures are frequently seen in our field. Since their possible complications can have an important impact on patients daily life, it is important to investigate the nature of these complications in order to avoid or minimize them as far as possible.

Materials and Methods

This study was evaluated and approved by the KU Leuven and UZ Leuven ethics committee (number S64257).

Patients

We retrospectively analyzed all patients with condylar fractures who were admitted to the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery at UZ Leuven between January 2013 and January 2020. In this study, condylar process fractures were interpreted as fractures in the head region, condylar neck of condylar base, according to the AOCMF classification.[

3] Inclusion criteria of this study were: patients with a unilateral or bilateral fracture of the condylar process, combined fractures of the condylar process and mandibular body, a minimal follow-up of 6 weeks after trauma. Exclusion criteria were: fractures of the condylar process combined with fractures other than the mandibular body, condylar fractures who received an endoscopic treatment. All patients were treated by the same team of maxillofacial surgeons, consisting of trained staff members assisted by maxillofacial trainees. All performed surgeries were open surgeries All in-house and referred patients with condylar process fractures were included and divided into 3 groups according to their initial treatment: patients who were treated conservatively, patients who received IMF in combination with conservative management, and patients who were treated with a combination of ORIF and IMF. A conservative treatment includes analgesia, a soft diet and physiotherapy. IMF was obtained by using elastics for a minimal period of 4-6 weeks. Collected data included age at the time of trauma, gender, anatomical side of the condylar fracture, associated fracture of the mandibular body, referrals, initial treatment, long-term complications, and secondary treatment. Long-term complications were defined as sequelae still present 6 weeks after trauma. Six weeks was chosen as a cut-off for 2 reasons. First, IMF on elastics was applied for a period of 4-6 weeks to let the fractures heal in a stable occlusion. Second, patients were seen on a regular base in the first week post trauma. Patients were seen 1, 2, 3 and 6 weeks post trauma. If patients presented sequelae with an important impact on daily life such as work absence, they were seen after 8, 10 and 12 weeks post trauma. If earlier complaints had improved or disappeared, the patient was excluded for this study.

Five major complications were noted: malocclusion, reduced mouth opening, nerve disturbances, pain, and facial asymmetry. Malocclusion was further divided into anterior open bite, crossbite, or general malocclusion. Nerve disturbances consist of a disturbance of the facial nerve (VII), mandibular nerve (V3), maxillary nerve (V2), or combined mandibular and maxillary nerve (V2/3). Secondary treatment of patients with long-term complications consisted of conservative treatment, such as analgesia and physiotherapy, or surgery.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by an external professional statistical bureau. The chi-squared test was used to compare the different variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient and Treatment Characteristics

Between January 2013 and January 2020, 252 condylar fractures were counted in 192 patients (81 females and 111 males). The mean age at the time of trauma was 35.7 years (range 2-95 years old). The Department of Maxillofacial Surgery at UZ Leuven Hospitals is a tertiary center; therefore, 46 patients (24.1%) were referred. A total of 132 patients (68.8%) presented with a unilateral condylar fracture and 60 (31.2%) with a bilateral condylar fracture. Eighty-eight patients (45.8%) presented with an associated fracture of the mandibular body, whereas a guardsman fracture or combined bilateral condylar fracture with mandibular body fracture occurred in 43 patients (22.4%). For primary treatment, 59 patients (30.7%) were treated conservatively with analgesic therapy and soft diet, 98 patients (51%) with IMF, and 35 patients (18.2%) received combined ORIF and IMF therapy. Ninety-three patients (48.4%) suffered from 1 or more long-term complications. Sixteen of the patients treated conservatively (27.1%) suffered from long-term complications, whereas 50 of the patients treated with IMF (51%) and 27 treated with combined ORIF and IMF (77.1%) complained of long-term complications.

The main long-term complaints at our department were malocclusion (24%), reduced mouth opening (15%), nerve dysfunction (13.5%), pain (8.9%), and facial asymmetry (2.6%). Malocclusion was divided into crossbite (0.5%), general malocclusion (6.2%), and anterior open bite (17.2%). Multiple causes of reduced mouth opening were identified: ankylosis (4.7%), bifid condyle (0.5%), condylar resorption (0.5%), condylar sag (0.5%), muscular tension (7.8%), or non-union of a fracture (1%). Nerve dysfunctions occurred as VII dysfunction (2.6%), V2 dysfunction (1%), V3 dysfunction (8.9%), and combined V2/ V3 dysfunction (1%). Pain was identified as articular pain (3.1%), muscular pain (4.7%), or neuropathic pain (1%). Conservative secondary treatment in patients suffering from long-term complications was used in 45 patients (23.4%), and 48 patients (25%) were in need of secondary surgery.

Statistical Analyses

The long-term complications in patients with unilateral condylar fractures were compared to those in patients with bilateral condylar fractures using chi-squared and the results reported in

Table 1.

Long-term complications in patients with an isolated unilateral or bilateral condylar fracture were compared to those in patients with condylar fractures and an associated fracture of the mandibular body using chi-squared and the results reported in

Table 2.

Long-term complications in patients without guardsman fracture were compared to those in patients with a guardsman fracture using chi-squared and the results reported in

Table 3.

The long-term complications in the 3 primary treatment subgroups were compared using the chi-squared and the results reported in

Table 4. A significant difference was measured between the different primary treatments in the prevalence of overall complications, between conservative treatment versus the IMF-treated patients in the prevalence of malocclusion, and between combined ORIF and IMF vs. conservative treatment and IMF in the prevalence of nerve dysfunction.

The prevalence of each complication was also compared between patients who received secondary conservative treatment and those who underwent secondary surgery using chi-squared and the results reported in

Table 5.

The 3 initial treatment subgroups were compared to the different secondary treatment groups (relationship p < 0.001) as shown in

Table 6.

Discussion

Previous studies have described complication rates of 7-29% after condylar fractures.[

3] These rates correlate with fracture severity, injury site, and the number of involved sites. Higher complication rates are described in smokers, patients with systemic illnesses, and patients with substance use.[

4,

14,

15] Of all the patients in this study who were admitted to the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery at UZ Leuven, 48.4% suffered from long-term complications, and this number is higher than reported in the literature. The difference from previous studies may be due to UZ Leuven being a tertiary center, with 24.1% of patients being referrals. Therefore, it is possible that these fractures were more complex and primary treatment already started elsewhere. This study confirms a significant relationship between the number of involved sites and the presence of long-term complications. We found that bilateral condylar fractures and guardsman fractures have a higher risk of developing long-term complications. We also found a significantly lower chance (p < 0.05) of developing long-term complications after conservative treatment compared to IMF or combined ORIF and IMF, or after initial treatment with IMF compared to combined ORIF and IMF. This relationship can be explained by patients with less complex fractures having a higher chance of receiving more conservative treatment and suffering fewer long-term complications.

Malocclusion

Malocclusion is one of the major complaints of patients with condylar fractures[

11] and is common immediately after trauma. If not treated properly, it can be persistent. Due to shortening of the ramus after dislocation of the fractured condyle and traction by the musculature on the ipsilateral ramus, a unilateral condyle fracture results in a contralateral open bite. In bilateral condyle fractures, a bilateral shortening of the ramus occurs and causes an anterior open bite.[

4,

5,

6,

11] In a retrospective study of 2458 patients with 2810 mandibular condylar fractures, malocclusion was reported more frequently in patients who were treated conservatively (11.1%) than in patients who received ORIF (4.0%).[

12] This study reports an overall malocclusion rate of 24% 6 weeks after the initial treatment. We found a significantly higher chance (p < 0.05) of developing malocclusion in bilateral fractures and guardsman fractures. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were also found in patients treated with IMF compared to those treated conservatively. This can be explained by minimally displaced fractures being treated conservatively and severely displaced fractures being treated mostly with IMF. This study revealed a significantly higher chance (p < 0.05) of secondary surgery when patients complain of persistent malocclusion.

Reduced Mouth Opening

Reduced mouth opening is a complaint in 8-10% of all condylar fractures and is usually present immediately after trauma but can persevere and worsen over time. Early mobilization should be considered to avoid reduced mouth opening, even at the expense of a stable occlusion.[

16,

17] The longer the period of IMF, the more hypo-mobility is described.[

13] Different causes of reduced mouth opening as a long-term complication have been described, including intracranial condyle, condylar sag, condylar resorption, bifid condyle, non-union, and ankylosis. An intracranial condyle is a rare condition caused by a high energetic trauma. A literature review revealed 51 previous cases in the English language.[

18] Condylar sag was first described by Hall in 1975 and can be described as a change in the position of the condyle in the glenoid fossa after establishing a proper occlusion.[

19,

20,

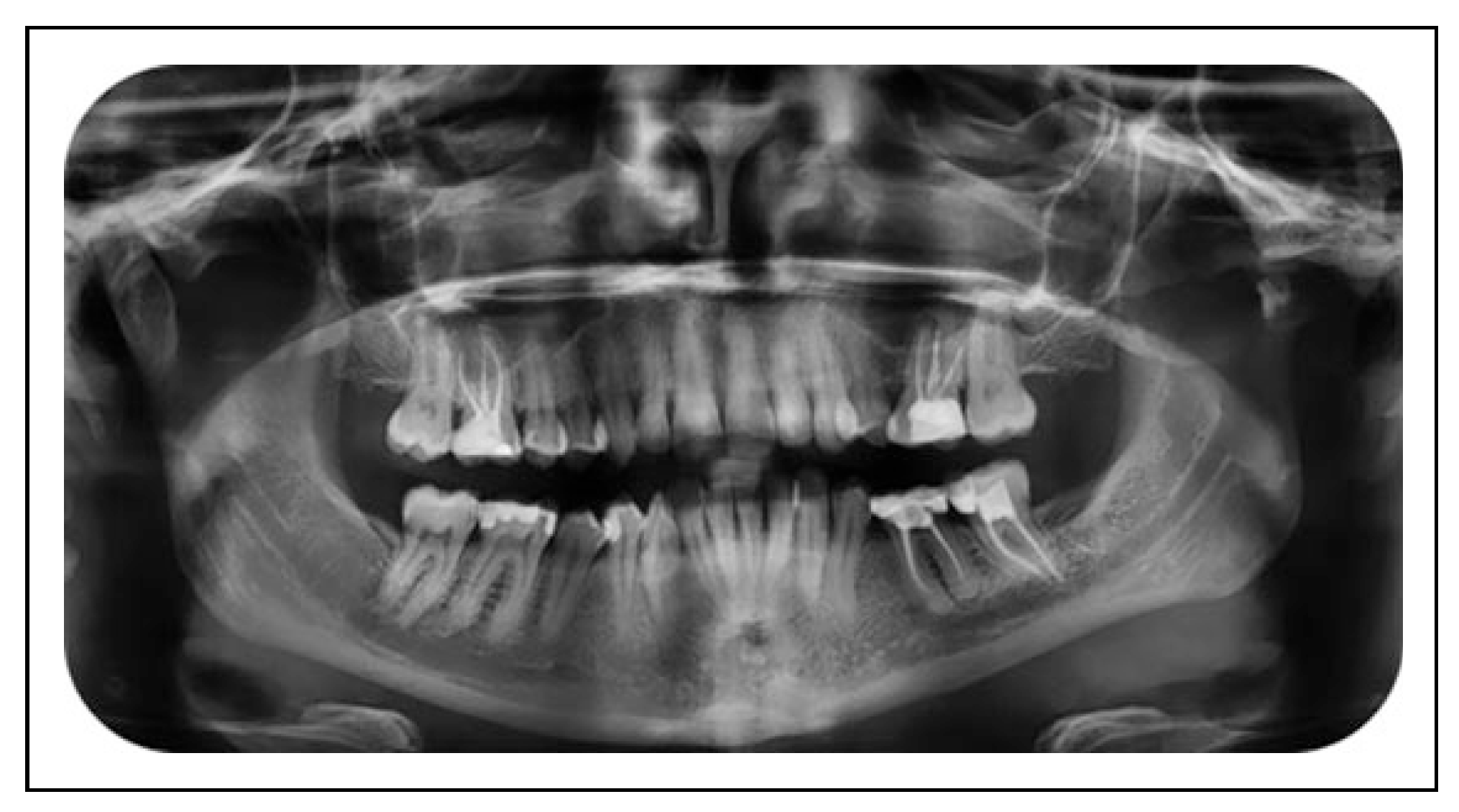

21] In 1 patient suffering from reduced mouth opening, condylar sag was thought to be the cause (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Although it is a rare cause of reduced mouth opening after trauma, a small amount of condylar resorption can be expected after condylar head fractures.[

22] A split condyle can heal and become a bifid condyle.[

23] Patients with a bifid condyle may or may not suffer from a reduced mouth opening.[

23,

24,

25] Non-union is a frequently described complication of condylar fractures[

4,

5,

14] and is defined as a mobility between 2 fractured segments. Ankylosis as a long-term complication is rare and has been described in 0.2% to 0.4% of condylar fractures.[

16] In the present study, 15.1% of all patients suffered from reduced mouth opening. We could not find a relationship in the distribution of this complaint by the number of involved sites, associated fracture of the mandibular body, or primary treatment. There seemed to be no relationship between the presence of a reduced mouth opening and preferred choice of secondary treatment.

Nerve Dysfunction

A rare complication in condylar fracture is nerve dysfunction, which can be divided into dysfunction of the mandibular nerve and facial nerve. Dysfunction of the mandibular nerve is usually caused by trauma, whereas dysfunction of the facial nerve occurs exclusively in ORIF patients. Unilateral displaced fractures of the condyle with an antero-median angulation of the condyle close to the foramen ovale have been described as a possible cause of mandibular nerve trauma.[

26] The presence of an enlarged lateral pterygoid plate enhances the risk of nerve compression. Mandibular nerve anesthesia should be considered an indication of ORIF for treatment of the condyle fracture.[

27] The incidence of facial nerve trauma in the retromandibular area following ORIF for condylar fractures exhibits broad variability, with incidences between 6% and 48%.[

1,

10,

19] In a retrospective study of 1909 patients with condylar fractures, 8.6% of all patients who received ORIF suffered from facial nerve trauma.[

12] Most of these complications were reversible within 6 months after treatment (8.3%), whereas irreversible facial nerve damage was described in 0.3%.[

12] This study shows an overall rate of nerve disturbance of 13.5%. A persistent facial nerve disturbance was present in 2.6%, and all of these patients underwent combined ORIF and IMF for primary treatment. Therefore, 14.3% of all patients who underwent primary combined ORIF and IMF suffered from facial nerve damage. Nerve disturbances of the mandibular and/or maxillary nerve were persistent in 10.9% of patients. A significantly higher chance of developing persistent nerve disturbances (p < 0.05) was seen in condylar fractures with associated mandibular fractures, guardsman fractures, and patients who were primarily treated with combined ORIF and IMF. This can be explained by the high number of fractures of the mandibular corpus through the mandibular canal. In the case of an associated fracture of the mandibular body, combined ORIF and IMF therapy is preferred. There seems to be no relationship between the presence of persistent nerve disturbances and the preferred choice of secondary treatment.

Pain

The cause of pain after condylar fractures can be articular, muscular, or neuropathic in origin. In a retrospective study of 2458 patients with 2810 mandibular condylar fractures, pain was described in 6.5% after conservative treatment and 5.6% after ORIF.[

12] Some studies[

28,

29] have described statistical differences between pain experience in patients who received conservative treatment and patients who received ORIF, but other studies could not confirm this.[

10] The present study found that 8.9% of all patients complained of persistent pain. Persistent pain seems to not be related to fracture type, an associated fracture of the mandibular corpus, or the type of initial treatment or preferred choice of secondary treatment.

Relationship Between Primary Treatment and Secondary Treatment

The choice of primary treatment in condylar fractures remains a controversial topic and depends on multiple factors. This study shows a significant relationship (p < 0.001) between the choice of primary treatment and secondary treatment. When a patient is primary treated conservatively, most patients will not develop long-term complications. If patients do have complications after a primary conservative treatment, there is a higher chance of secondary surgery instead of secondary conservative treatment consisting of physiotherapy and adequate analgesia. Approximately half of patients treated with IMF did not suffer from any complication and, therefore, did not require secondary treatment. Patients presenting with long-term complications after IMF were treated surgically or received conservative secondary treatment. In the case of primary combined ORIF and IMF treatment, most patients suffered from long-term complications, and most of these patients were treated conservatively; 31.4% underwent a secondary surgery.

Study Limitations

This study has limitations. First, this study was performed in a tertiary center, so 24.1% of our patients were referred from other hospitals where they received the primary treatment. Second, although the operating team consisted of experienced staff members and maxillofacial trainees, not all traumas were treated surgically by the exact same team. Third, this study did not include an initial severity score since this was a retrospective study and 24.1% of our patients already received a primary treatment in another hospital.