Abstract

Study Design: This is a retrospective case series using the Thomson Reuters Westlaw Edge database, an online subscription- based database of over 40,000 state and federal records. Objective: There is growing academic interest in the medicalmalpractice literature. The primary objective of this study was to examinemedical malpractice in orthognathic procedures in order to characterize factors that determine legal responsibility and help make the craniomaxillofacial (CMF) surgeon more comfortable when treating this patient population. Methods: The database was queried for medical malpractice cases involving orthognathic surgery from 1985–2021. The characteristics of each lawsuit were identified, and descriptive statistics were reported. Results: A total of 42 CMF malpractice cases were available for review, and total of 15 cases were included in the final sample. Verdict decisions and settlements occurred between 1991 and 2012. Of the 15 cases, the highest concentration of cases occurred in California (6) and Pennsylvania (2). 53% of cases were ruled in favor of the defendant, 7% of cases were settled, 27% of cases were ruled in favor of the plaintiff against the surgeon, and 13% were ruled in favor of the plaintiff against the hospital with the surgeon being found not liable. The minimum award of damages was $29,999 and the maximum was $550,000. Conclusion: Litigation experience can be very time consuming and troublesome for medical practitioners. The risk of litigation and complications might be a prohibiting factor as to why CMF surgeons may not be preforming orthognathic surgery. The best defense against a malpractice case is to avoid one altogether. Learning from past mistakes is one way of ensuring that goal.

Introduction

Medical malpractice litigation appears to be increasing in recent decades, and in response there has been a robust wave of literature on this topic.[1,2] To the authors’ knowledge there has been no such analysis on elective orthognathic surgery procedures. When reviewing case law, it is important to focus on specific procedures rather than entire subspecialties. Lawsuits involving facial trauma often involve litigation against multiple parties and carry alterior motives outside of medical malpractice on the provider. Therefore, combining these cases with facial cosmetic cases can introduce significant heterogeneity. A comprehensive review of litigation related solely to elective orthognathic surgery is important as treatment diagnoses, risks, and goals are relatively constant across procedures. The primary objective of this study was to examine medical malpractice in orthognathic surgery by presenting variables that were associated with legal responsibility in past cases.

Methods

To address the research purpose, the investigators designed and implemented a retrospective case series to identify and describe variables associated with legal responsibilities in prior malpractice cases. The study population was composed of all cases present in the Thomas Reuters Westlaw Edge database, an online subscription-based legal research service that contains case law and related data from more than 40,000 databases of state and federal records. On January 4th 2021, the Westlaw Edge database was queried using the following search term for verdicts and settlements from 1/1/1985 through 1/1/2021: [(“Orthognathic” OR “Orthosurgery” OR “Jaw Surgery” OR “Lefort” OR “BSSO” OR “Bilateral sagittal split osteotomy” OR “IVRO” OR “vertical ramus osteotomy”) AND “Malpractice”].

Court summaries of the resulting cases were individually reviewed. In order to be included in the study sample, cases were required to involve orthognathic surgery. Cases were excluded from the study sample if they were dismissed prior to trial, dismissed during trial, or were appealed and successfully reversed and remanded to the lower courts. Among the final sample of included cases, both case summaries and internet searches were used to gather data on the defendants’ and plaintiffs’ characteristics. The recorded information included the medical or surgical sub-specialty, the geographic location, the allegations (procedural negligence, deformity, and informed consent), the verdicts, any awards, and any appeal results. As per Columbia University Irving Medical Center, research involving the analysis of de-identified data in publicly available datasets does not qualify as “research” with “human subjects” (per applicable federal regulation) and therefore does not require independent ethical review.

Results

A total of 42 CMF malpractice cases were identified using the aforementioned search terms. After removing duplicates, 38 malpractice unique cases were hand reviewed and cross-referenced with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Ultimately, 15 cases were suitable and included in the final study sample. All verdict decisions occurred between the years of 1991 and 2012. Among our sample of cases, the highest concentration of cases occurred in California (6) followed by Pennsylvania (2). 53% of cases were ruled in favor of the defendant, 7% of cases were settled, 27% of cases were ruled in favor of the plaintiff against the surgeon, and 13% were ruled in favor of the plaintiff against the hospital with the surgeon being found not liable (Figure 1). The minimum award of damages was $29,999, and the maximum award was $550,000 (mean: $293,123.29, SD: $207,480.08). Most of the plaintiffs were female (67%), and patient ages ranged between 27 and 71 years (mean: 34y, SD: 10y).

Figure 1.

Verdict outcomes.

Review of the Case Law

The purpose of this study was to present factors associated with legal responsibility in orthognathic surgery in order to help CMF surgeons learn from shared experiences. The first step in analyzing malpractice litigation is to understand the underlying fuel of the lawsuit. In most instances, lawsuits occur due to patient dissatisfaction and poor communication. Litigation often centers around a major complication that the patient (plaintiff) claims to be unusual, unexpected, or caused because the provider acted outside the standard of care.

Informed consent involves educating the patient on the potential risks and benefits of the proposed procedure so that they can make an informed decision on whether or not they would like to continue with treatment. It is not only an ethical responsibility of a physician to inform the patient of any pertinent information prior to starting treatment, but also a legal obligation. A physician who fails to obtain proper informed consent leaves himself vulnerable to losing malpractice lawsuits that will inevitably arise over the course of a career. Four criteria need to be met during the informed consent: (1) the specific procedure details, (2) the risks and benefits, (3) any reasonable alternative treatments, and (4) the risks and benefits any alternatives. In addition to these criteria, the patient must have decision making capacity and understand the discussion related to the 4 criteria.[3]

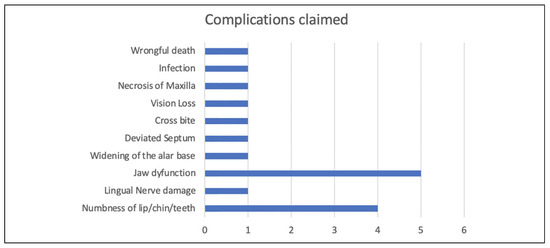

Our case narratives contained a few notable patient complications and trials decisions. Figure 2 presents the complications that orthognathic surgery patients alleged, and the most common complaint was jaw dysfunction and numbness. Interestingly, 1 patient endorsed postoperative numbness to the tongue and jaw with difficulty speaking, which is suggestive of lingual nerve damage. Although permanent numbness of the lower lip and chin is known to occur,[4] damage to the lingual nerve is extremely rare in orthognathic surgery. A review of 100 mandibular osteotomy patients found that the incidence of permanent injury to the lingual nerve was only 2/100 patients.[5,6] In another malpractice case, a patient suffered permanent numbness to his maxillary gums and teeth following a Lefort 1 osteotomy. The patient claimed that the surgeon placed 2 plates for rigid fixation when the standard of care was 4 plates. The patient also complained that the treating surgeon failed to bone graft the osteotomy gap, that steel wires should have been used instead of elastic bands for intermaxillary fixation, and that the planned 9 mm advancement was excessive. Ultimately, the surgeon was found not liable in this case, however the plaintiff’s multiple claims, although clearly unrelated to the alleged complication of maxillary numbness, demonstrate how specific and misguided litigation charges can be. A third jaw surgery patient sued their surgeon after losing 90% vision in the right eye and partial vision in left eye. It was found that she was not properly monitored postoperatively, and that excessive hypotension directly causes her vision loss. That plaintiff won her case and was awarded $502,000. In a separate case, a reciprocating saw malfunction was blamed for a patient’s a severe postoperative infection that ultimately required a tracheotomy. Only the hospital, and not the surgeon, was penalized and found liable for the defective equipment.

Figure 2.

Complications claimed in the lawsuit.

Orthognathic surgery is associated with a wide range of known complications. Comprehensive literature reviews on this matter have been performed to determine the relative frequencies of these complications. Unexpected hemorrhage has been found to be the most concerning intraoperative mishap and occurs in up to 9% of cases. Potential damage to the inferior and superior alveolar, maxillary, retromandibular, facial, and sublingual vessels requires swift and definitive. Unfavorable splits with sagittal ramus osteotomies are another common surgical complication that occur in roughly 2.3% of cases.[7] Postoperatively, nerve damage is the most commonly reported postoperative complication and occurs in up to 12.1% of patients. Infection is second most common complication reported, and hardware problems are the third most common source of complications. These are followed by temporomandibular joint disorders (2.1%), undue fractures (1.8%), and scarring (1.7%).[8] While postoperative complications are only seen in a small fraction of all orthognathic procedures, it is important to discuss the their possibility with all patients prior to treatment.[7]

Our case series also demonstrates that with proper defensive actions not allmalpractice caseswill result in devastation. In 1 case, a patient sued her surgeon and the treating hospital following a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy, claiming to have suffered lip numbness, jaw dysfunction, and inability to open hermouth fully. This trial found that proper informed consent was indeed obtained and that the surgeon and hospital were therefore not liable for this unfortunate complication. Another patient suffered maxillary necrosis following orthognathic surgery. The lack of blood flow resulted in the loss of 10 teeth, a permanent hole in the patient’s palate, speech impediment, and severe weight loss. Since the surgeon documented proper informed consent, the surgeon was not found liable in this case. Another instance, a patient suffered a stroke following a Lefort 1 osteotomy. The patient’s daughter sued the surgeon for wrongful death and claimed negligence during the procedure that resulted in internal carotid artery damage. That case was settled for $29,999, which was the lowest amount awarded in our series. In fact, all trial verdicts resulted in higher payouts than this settlement. This highlights the fact that payouts of settlements are often smaller than that of trial verdicts, even with severe complications.

The case data gathered for this study have several notable limitations. First, our sample only represents a fraction of the more than 100,000 malpractice claims brought during the searched time period. Therefore, our sample may not be representative of the entire population of orthognathic malpractice lawsuits. However, we believe that the narrative information gleaned from the case law is more beneficial than the number of cases reviewed, as it is more important to understand the themes behind why legal action is pursued. Legal case databases do not contain the same amount of medical documentation as one would hope when conducting this type of study. Case files often describe the surgical procedures in lay terms, and many of the cases simply referred to the procedure in question as jaw surgery or orthognathic surgery without specifying the osteotomies.

All the of the common and uncommon complications we have identified in this series should be routinely discussed with orthognathic patients.[9] With the exception of 1 case (wrongful death secondary to stroke), all of the alleged complications noted in this review are reasonably possible complications that any CMF surgeon preforming orthognathic surgery could encounter over the course of a career. Malpractice lawsuits are not unilaterally devastating to the surgeon and appear to be less damaging when proper defensive measures are documented.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- He, P.; Mah-Ginn, K.; Karhade, D.S.; et al. How often do oral maxillofacial surgeons lose malpractice cases and why? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019, 77, 2422–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halepas, S.; Lee, K.C.; Higham, Z.L.; Ferneini, E.M. A20-year analysis of adverse events and litigation with light-based skin resurfacing procedures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020, 78, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.T.; Turrin, D. Informed Consent. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, January 2021; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430827/ (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Choi, B.K.; Lee, W.; Lo, L.J.; Yang, E.J. Is injury to the inferior alveolar nerve still common during orthognathic surgery? Manual twist technique for sagittal split ramus osteotomy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018, 56, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McLeod, N.M.; Bowe, D.C. Nerve injury associated with orthognathic surgery. Part 3: lingual, infraorbital, and optic nerves. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016, 54, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, N.M.; Bowe, D.C. Nerve injury associated with orthognathic surgery. Part 2: inferior alveolar nerve. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016, 54, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-K. Complications associated with orthognathic surgery. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017, 43, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, C.S.; Turrini, R.N.T. Complications in orthognathic surgery: a comprehensive review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2012, 24, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Boffano, P.; Gallesio, C.; Garzaro, M.; Pecorari, G. Informed consent in orthognathic surgery. Craniomaxillofac Trauma & Reconst. 2014, 7, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

© 2021 by the author. The Author(s) 2021.