Children in Boxing and Martial Arts Should Be Better Guarded from Facial Injuries

Abstract

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sample

Variables

Data Collection

Statistical Analysis

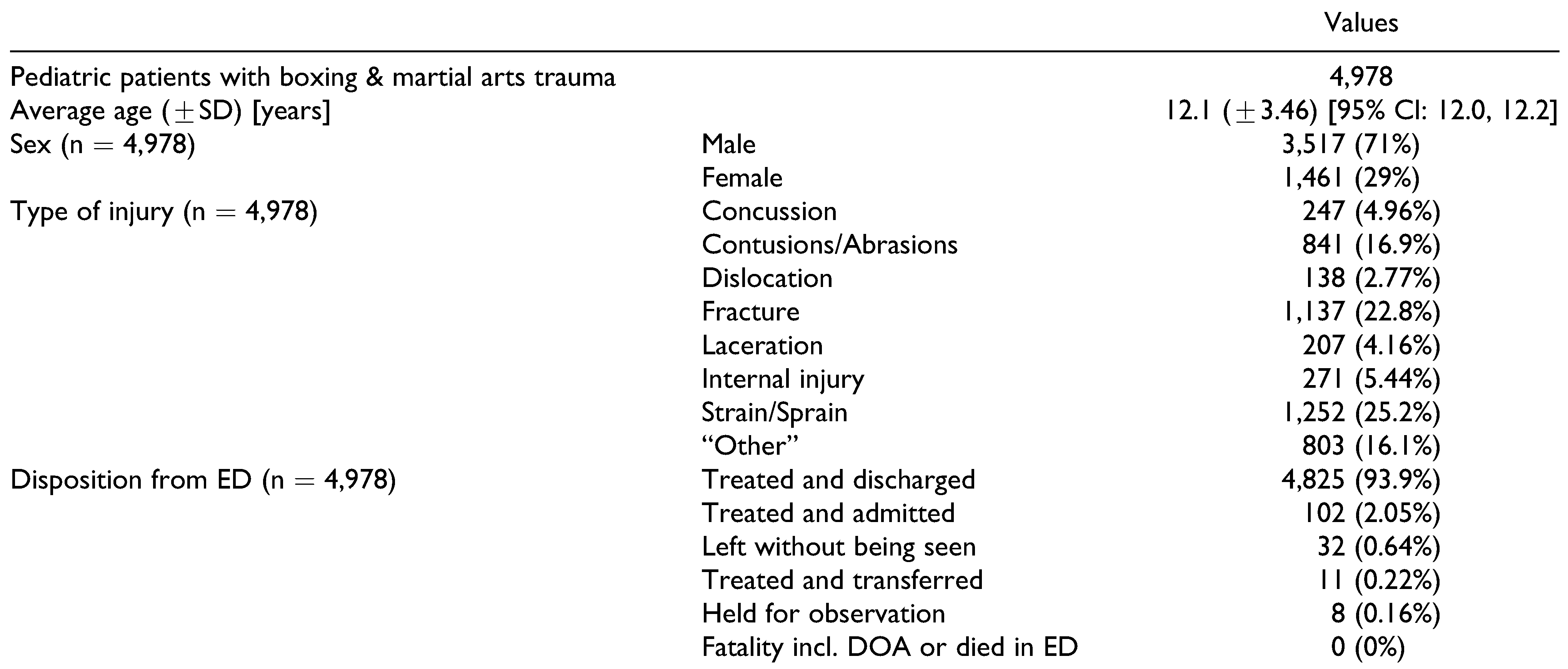

Results

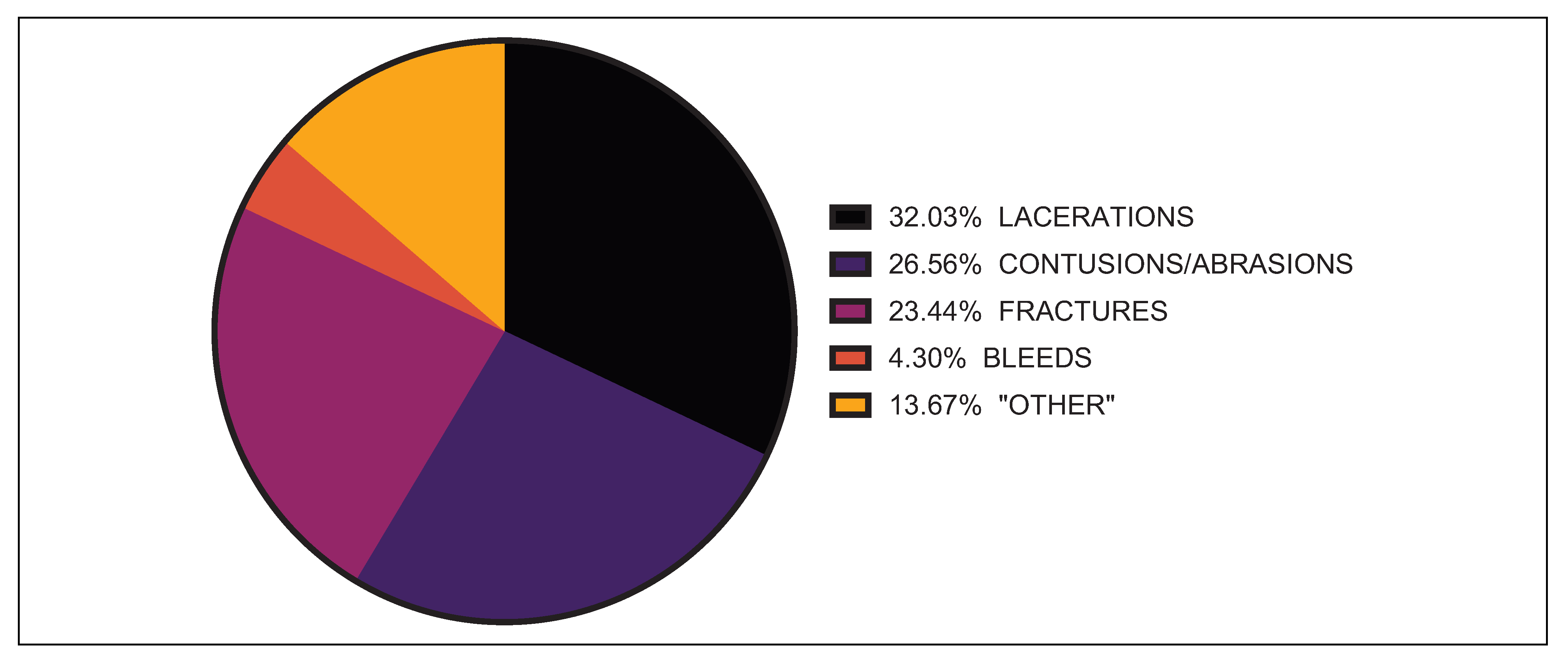

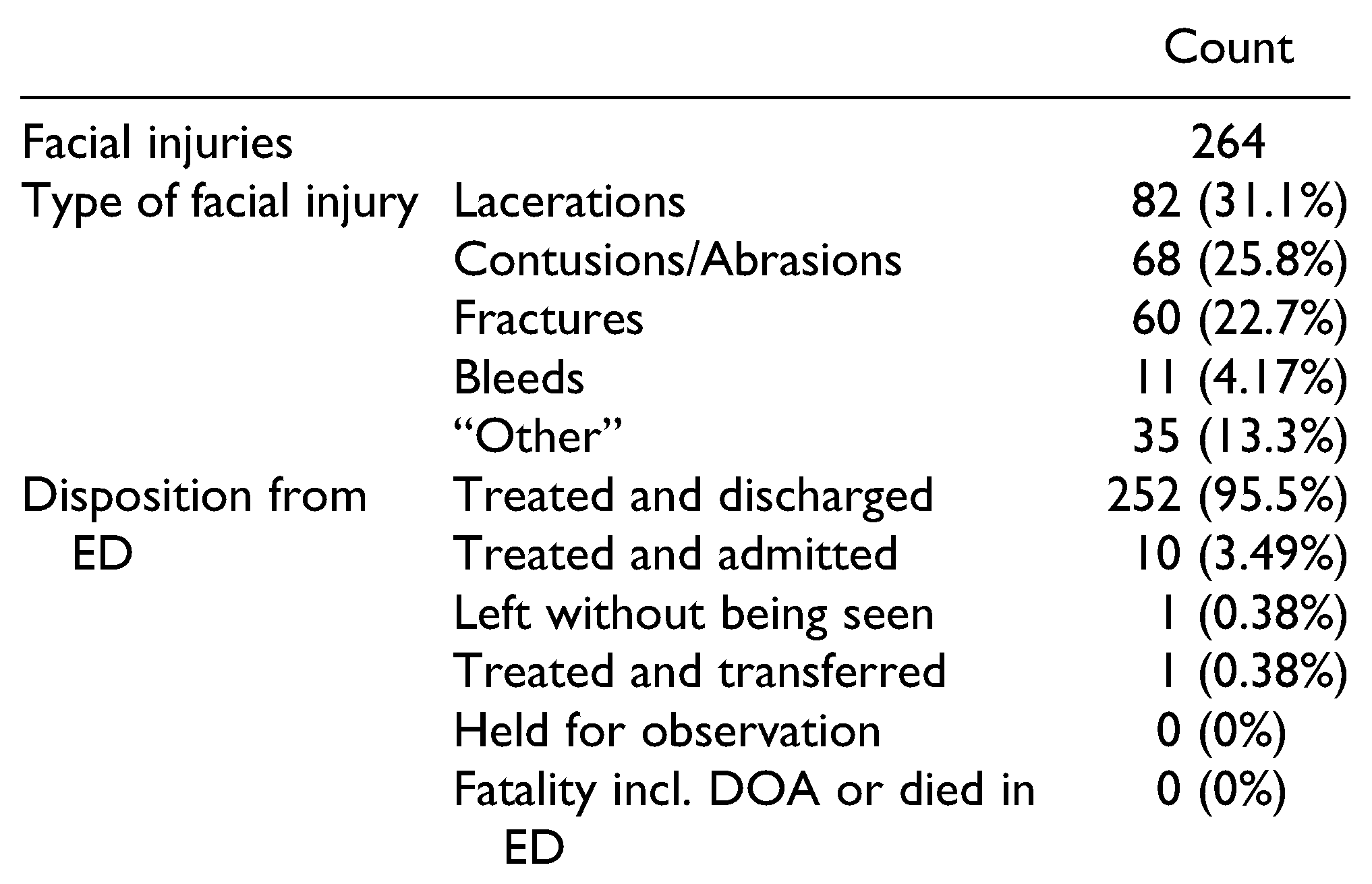

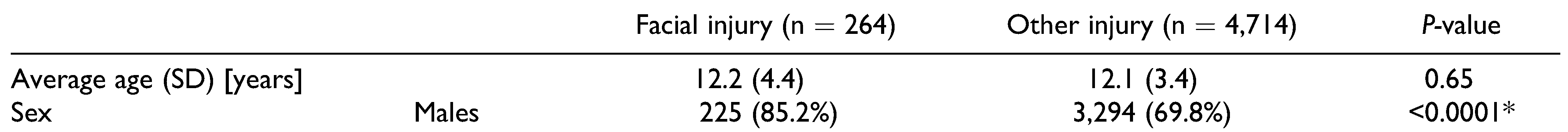

Facial Injuries

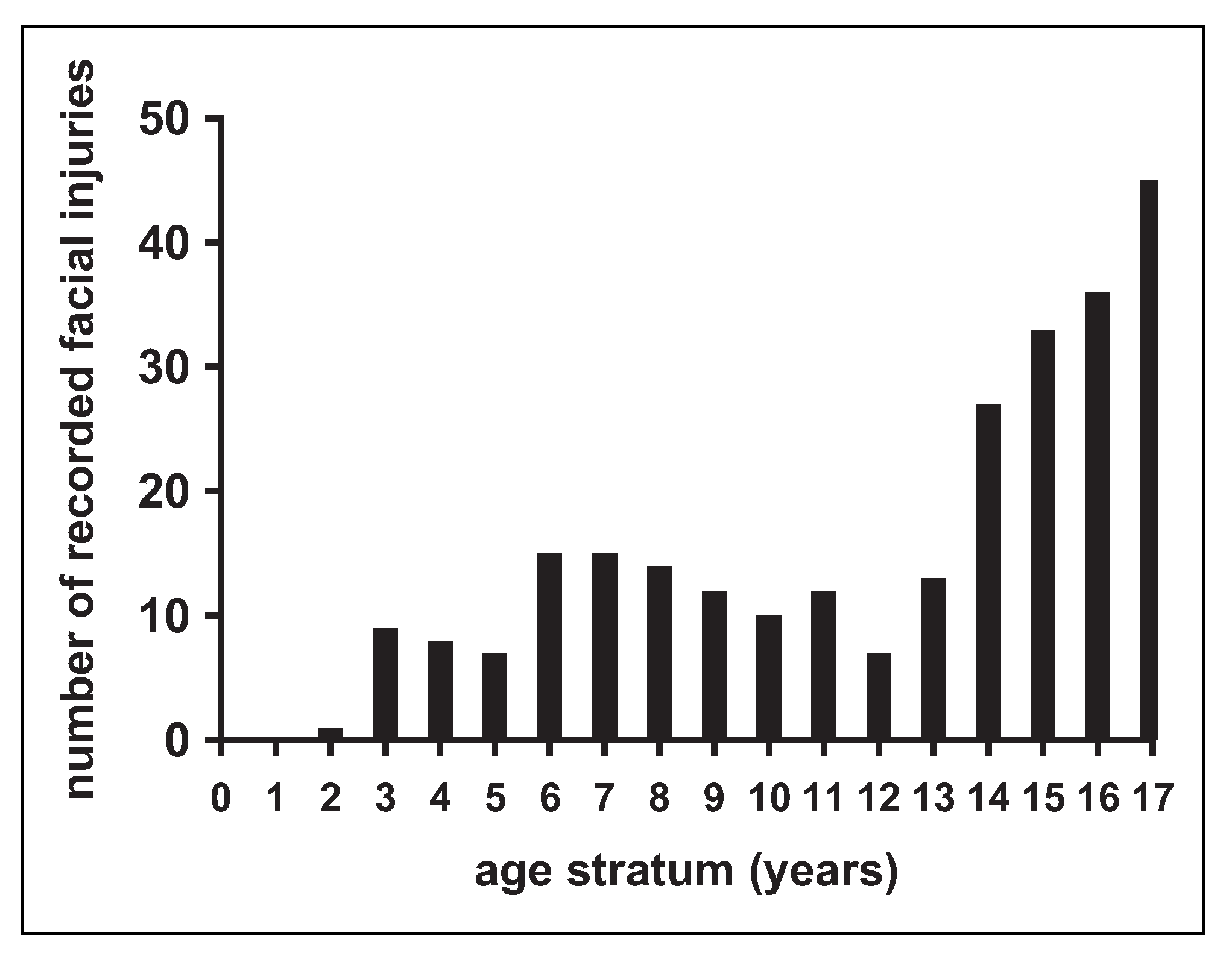

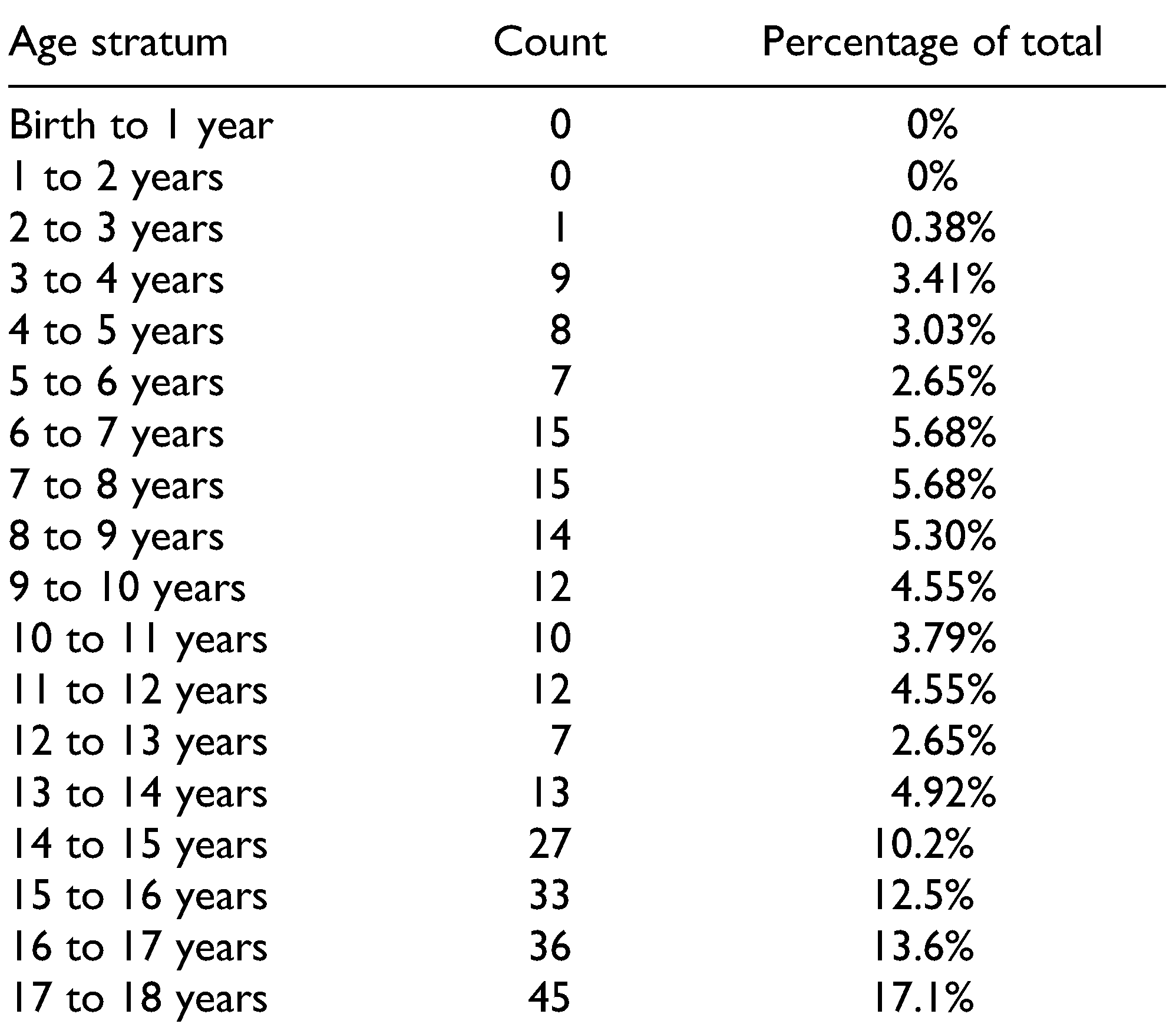

Age Trends Among Pediatric Patients With Facial Injuries

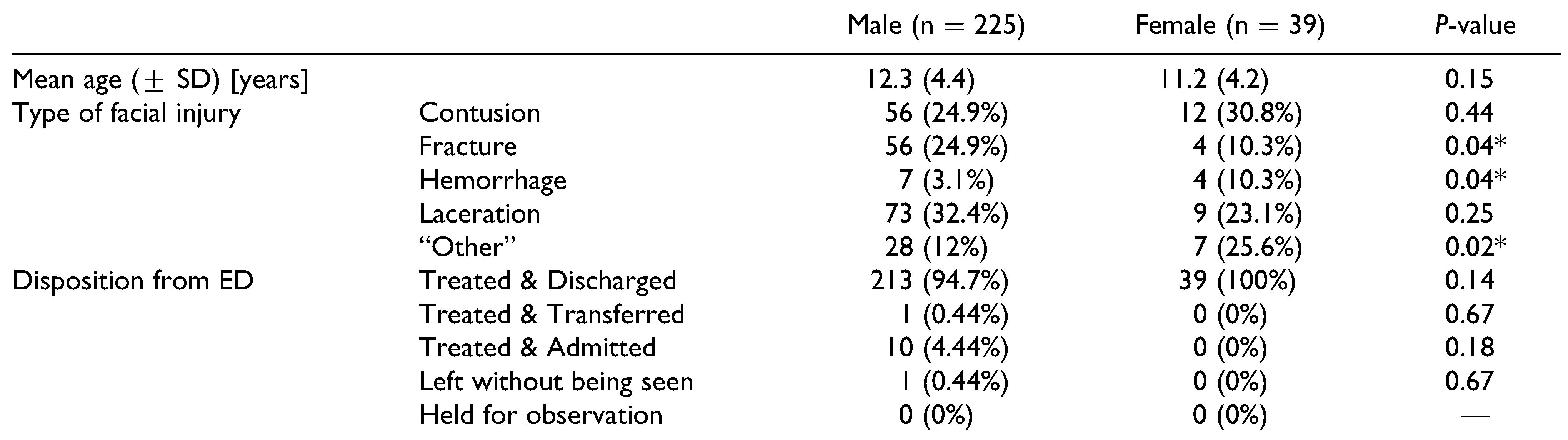

Sex Trends Among Pediatric Patients With Facial Injuries

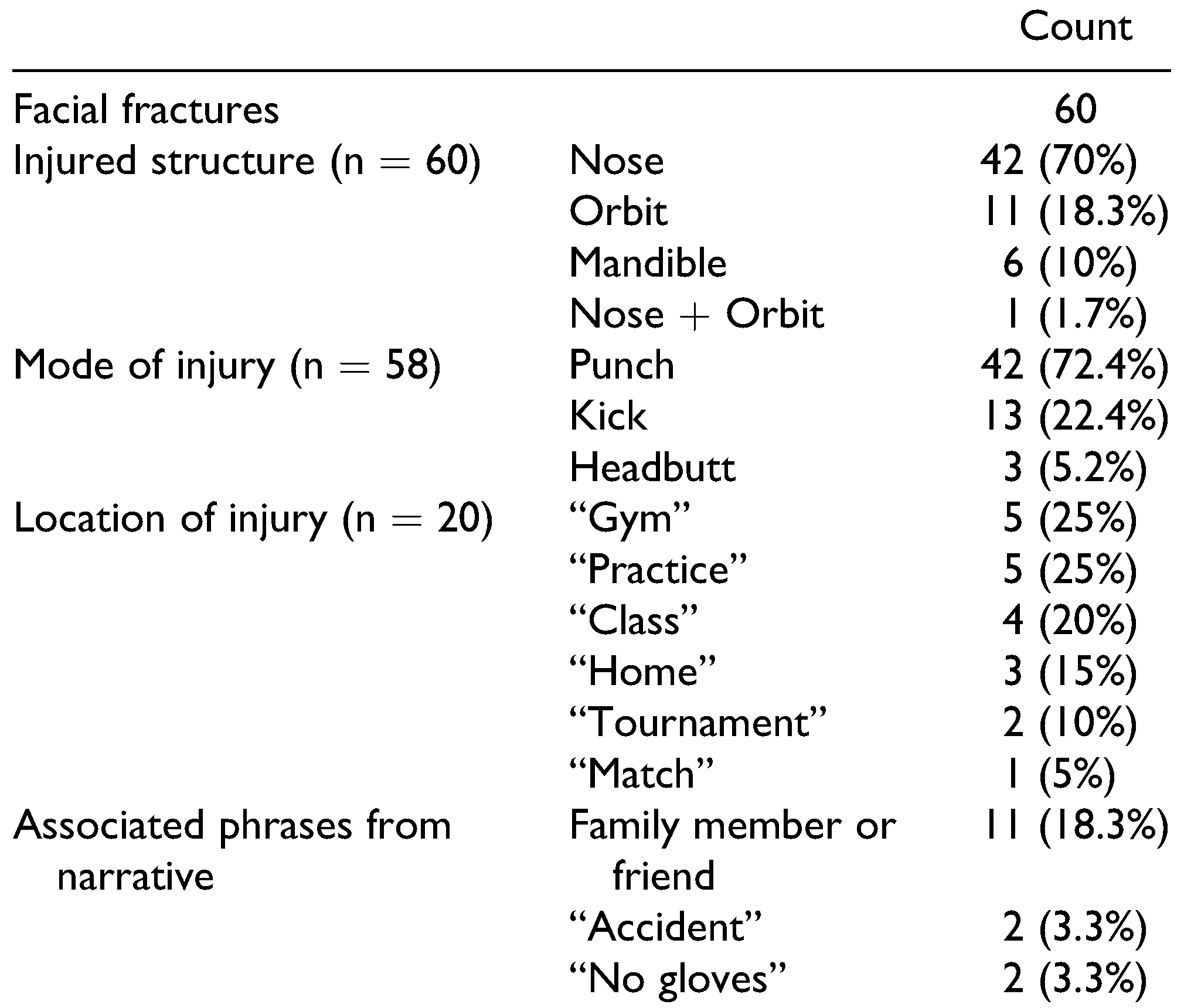

Location and Characteristics of Pediatric Facial Fractures

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pappas, E. Boxing, wrestling, and martial arts related injuries treated in emergency departments in the United States, 2002-2005. J Sports Sci Med. 2007, 6, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hojjat, H.; Svider, P.F.; Lin, H.S.; et al. Adding injury to insult: a national analysis of combat sport-related facial injury. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016, 125, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchison, M.G.; Lawrence, D.W.; Cusimano, M.D.; Schweizer, T.A. Head trauma in mixed martial arts. Am J Sports Med. 2014, 42, 1352–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffler, P.; Wolter, N.E.; Namavarian, A.; Propst, E.J.; Chan, Y. Contact sport related head and neck injuries in pediatric athletes. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 121, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, A.M.S.; Lima-Neto, T.J.; Mendes, B.C.; et al. Social consequences of injuries in pediatric facial trauma after motorcycle accident. J Craniofac Surg. 2020, 31, 329–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.L.; Cohen-Kerem, R.; Ngan, B.Y.; Forte, V. Posttraumatic facial artery aneurysm in a child. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004, 68, 1539–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission CPS. The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System: A Tool for Researchers. 2000. Published March 2000. Available online: https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fspublic/ pdfs/blk_media_2000d015.pdf (accessed on February 2021).

- Schroeder, T.; Ault, K. The NEISS Sample (Design and Implementation) 1997 to Present. 2001. Published June 2001. Available online: https://cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/ 2001d010-6b6.pdf (accessed on February 2021).

- Ashar, A.; Kovacs, A.; Khan, S.; Hakim, J. Blindness associated with midfacial fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998, 56, 1146–1150; discussion 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulcher, T.P.; Sullivan, T.J. Orbital roof fractures: management of ophthalmic complications. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003, 19, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, I.C.; Kordahi, A.M.; Paik, A.M.; Lee, E.S.; Granick, M.S. Examination of life-threatening injuries in 431 pediatric facial fractures at a level 1 trauma center. J Craniofac Surg. 2014, 25, 1825–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.C.; Amarante, J.M.; Silva, P.N.; et al. Retrospective study of 1251 maxillofacial fractures in children and adolescents. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005, 115, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khateeb, T.; Abdullah, F.M. Craniomaxillofacial injuries in the United Arab Emirates: a retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007, 65, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, L.K.; Leblanc, C.M. Canadian Paediatric Society HALaSMC, American Academy of Pediatrics, Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Boxing participation by children and adolescents: a joint statement with the American Academy of Pediatrics. Paediatr Child Health. 2012, 17, 39–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sorenson, T.J.; Borad, V.; Schubert, W. A nationwide study of skiing and snowboarding-related facial trauma. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, T.J.; Borad, V.; Schubert, W. Facial injuries due to cycling are prevalent: improved helmet design offering facial protection is recommended. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Stuart, M.J.; Smith, A.M.; Malo-Ortiguera, S.A.; Fischer, T.L.; Larson, D.R. A comparison of facial protection and the incidence of head, neck, and facial injuries in junior A hockey players. A function of individual playing time. Am J Sports Med. 2002, 30, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Moeller, E.; Thaller, S.R. Sports-related craniofacial injuries among pediatric and adolescent females: a national electronic injury surveillance system database study. J Craniofac Surg. 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partiali, B.; Oska, S.; Barbat, A.; Sneij, J.; Folbe, A. Injuries to the head and face from skateboarding: a 10-year analysis from national electronic injury surveillance system hospitals. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020, 78, 1590–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carniol, E.T.; Shaigany, K.; Svider, P.F.; et al. “Beaned”: a 5-year analysis of baseball-related injuries of the face. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015, 153, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbronn, C.M.; Svider, P.F.; Folbe, A.J.; et al. Burns in the head and neck: a national representative analysis of emergency department visits. Laryngoscope. 2015, 125, 1573–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, L.A.; Svider, P.F.; Raza, S.N.; Zuliani, G.; Carron, M.A.; Folbe, A.J. Hockey-related facial injuries: a population-based analysis. Laryngoscope. 2015, 125, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga, H.S.; Fisher, P.B.; Tasian, G.E.; et al. Sports-related genitourinary injuries presenting to United States emergency departments. Urology. 2015, 85, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|

|

|

|

|

© 2021 by the author. The Author(s) 2021.

Share and Cite

Gotlieb, R.J.; Sorenson, T.J.; Borad, V.; Schubert, W. Children in Boxing and Martial Arts Should Be Better Guarded from Facial Injuries. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2022, 15, 104-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211016666

Gotlieb RJ, Sorenson TJ, Borad V, Schubert W. Children in Boxing and Martial Arts Should Be Better Guarded from Facial Injuries. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2022; 15(2):104-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211016666

Chicago/Turabian StyleGotlieb, Rachael J., Thomas J. Sorenson, Vedant Borad, and Warren Schubert. 2022. "Children in Boxing and Martial Arts Should Be Better Guarded from Facial Injuries" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 15, no. 2: 104-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211016666

APA StyleGotlieb, R. J., Sorenson, T. J., Borad, V., & Schubert, W. (2022). Children in Boxing and Martial Arts Should Be Better Guarded from Facial Injuries. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 15(2), 104-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211016666