Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic (COVID) caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus[

1] had a direct impact on the healthcare systems. As of January 1, 2021, there were 73,512 deaths due to COVID reported in the United Kingdom (UK).[

2] During 2020, there have been numerous lockdowns and social distancing measures implemented in the UK after the first reported case in January 2020.[

3] Many studies have demonstrated the impact of such measures on healthcare services around the world, with reduced numbers of patients presenting to ED and being admitted to hospital.[

4,

5] This was reflected in the UK with a reduction in ED attendances, primary care utilization and outpatient referrals since the onset of the pandemic.[

6] In terms of trauma, there was a 54% reduction in trauma attendances during lockdown.[

7]

Nasal fractures are the third most commonly fractured bone in the body and the most common facial fracture. They account for more than 50% of all facial fractures in adults, likely due to the anterior projection of the nose on the face.[

8,

9] Nasal fractures are most frequently seen in males between the age of 15 to 30 years.[

10,

11] The most common mechanism of injury is blunt-force trauma, usually secondary to road traffic accidents (RTA), sports injuries, or physical assault.[

11,

12]

Initially assessment of nasal fractures is usually undertaken in the emergency department (ED) through history, and examination of the nose. Externally, it is usually difficult to clinically assess for a nasal fracture due to significant facial edema, unless the presentation is within the first few hours following nasal injury. Internal examination is important to examine both nasal passages for epistaxis, septal hematoma and evidence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhoea.[

9,

13] Generally, imaging is not necessary in the assessment of nasal bone fractures, although maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scans can be employed if there is suspicion of other facial injuries.[

14,

15]

Definitive management of nasal fractures is usually on an outpatient basis with patients being referred for assessment in ear, nose and throat (ENT) emergency clinics. This is to allow any facial edema to resolve to allow for a more accurate evaluation of nasal deformity. It is generally accepted that patients should be seen within 10 to 14 days to avoid fracture malunion which would pose an increased difficulty in subsequent correction, even under general anesthetic.[

16] Our center aims to assess patients within 10 days of initial injury. This falls in line with studies that suggest manipulation within this time period can minimize the risk of secondary nasal deformities.[

17,

18,

19]

Assessment in ENT emergency clinic involves shared decision making with the patient to decide; (1) whether there is a fracture, (2) if this needs to be corrected, and (3) what method of correction is most suitable. If a fracture needs correction, usually a manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) is performed on the same day under local anesthesia. This is generally the preferred method of management by ENT doctors and has shown to have good outcomes.[

20,

21,

22] Studies have suggested 79% to 91% of patients were satisfied with their outcomes post-MUA with only 3% progressing to surgical intervention.[

23,

24]

The authors hypothesize that the number of nasal fracture patients seen in the ENT emergency clinic at a major trauma center (MTC) would decrease during 2020 due to the impact of COVID. The specific aims were to (1) measure and compare the frequency of nasal fracture patients during the pandemic to the year prior and (2) evaluate the time of follow up and the management strategies (clinic outcomes) between the 2 groups.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed on all patients with suspected or confirmed nasal bone fractures presenting to ED between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2020 at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham.These patients were identified by the coding department through OCEANO PAS. Identified patients were retrospectively analyzed in 2 groups depending on the year they were seen. This reflected the impact of social distancing measures and lockdown as a result of COVID on the UK healthcare system. The pre-COVID cohort (control group) were identified as patients seen in ENT emergency clinic in between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2019. The COVID cohort (experimental group) were identified as patients seen in the ENT emergency clinic between January 1, 2020 and December 31, 2020. Case notes were retrospectively analyzed on the digital system used in our center (PICS).

Data was extracted for patient age, gender, days to follow up in ENT emergency clinic after initial injury and clinic outcome (discharge, intervention with MUA or rhinoplasty, or did not attend; DNA). Exclusion criteria were patients who had no nasal fracture confirmed on imaging, who were incorrectly coded or had incomplete records, who self-discharged before assessment in ED, or who were referred for ENT emergency clinic assessment out-of-area.

Collected data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics version 27.0.1.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). All patient identifiable information was anonymized and not stored. Graphs were produced using MS Excel® version 16.31 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Basic descriptive statistics, chi-squared (χ2) and t-tests were used to analyze the data where valid. A p-value of <.05 was deemed as the accepted value of statistical significance in all applicable analysis. Ethical approval was not required as this was a retrospective study as per the National Code on Clinical Trials.

Results

There was a total of 122 patients identified with suspected or confirmed nasal bone fractures between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2020. A total of 104 patients were included in the final analysis after 18 patients were excluded (6 had no confirmed nasal fracture on CT imaging, 5 patients were incorrectly coded or had incomplete records, 2 patients self-discharged before initial assessment in ED and 5 patients had ENT emergency clinic follow up arranged out-of-area).

Patient Demographics

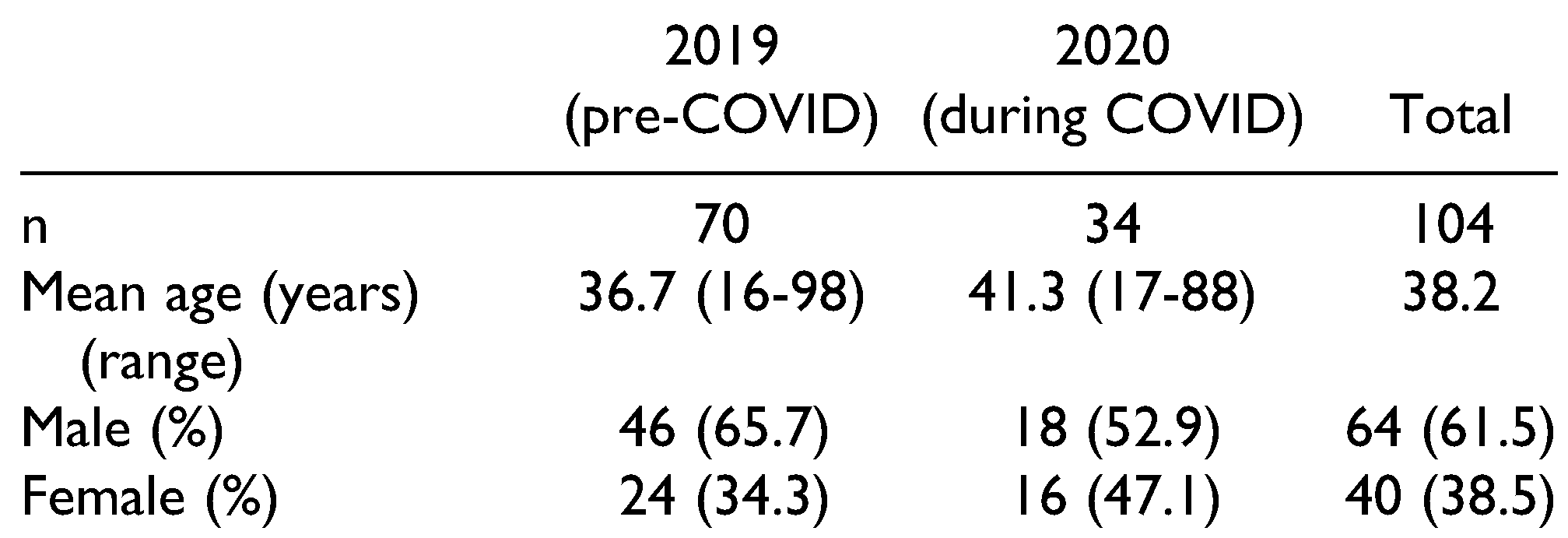

In thewhole patient cohort (2019 and 2020 combined). There were 64 males (61.5%) and 40 females (38.5%). The mean age of included patients was 38.2 years (range 16-98 years). When comparing the 2019 (pre-COVID) and 2020 (during COVID) cohorts, there were more patients seen in 2019 (n = 70) than in 2020 (n = 34). This represented a 51.4% decrease. The average age of patients seen in 2019 was 36.7 years with 46 males (65.7%) and 24 females (34.3%). In 2020, the average age was 41.3 years with 18 males (52.9%) and 16 females (47.1%). These baseline characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

Patient Follow Up

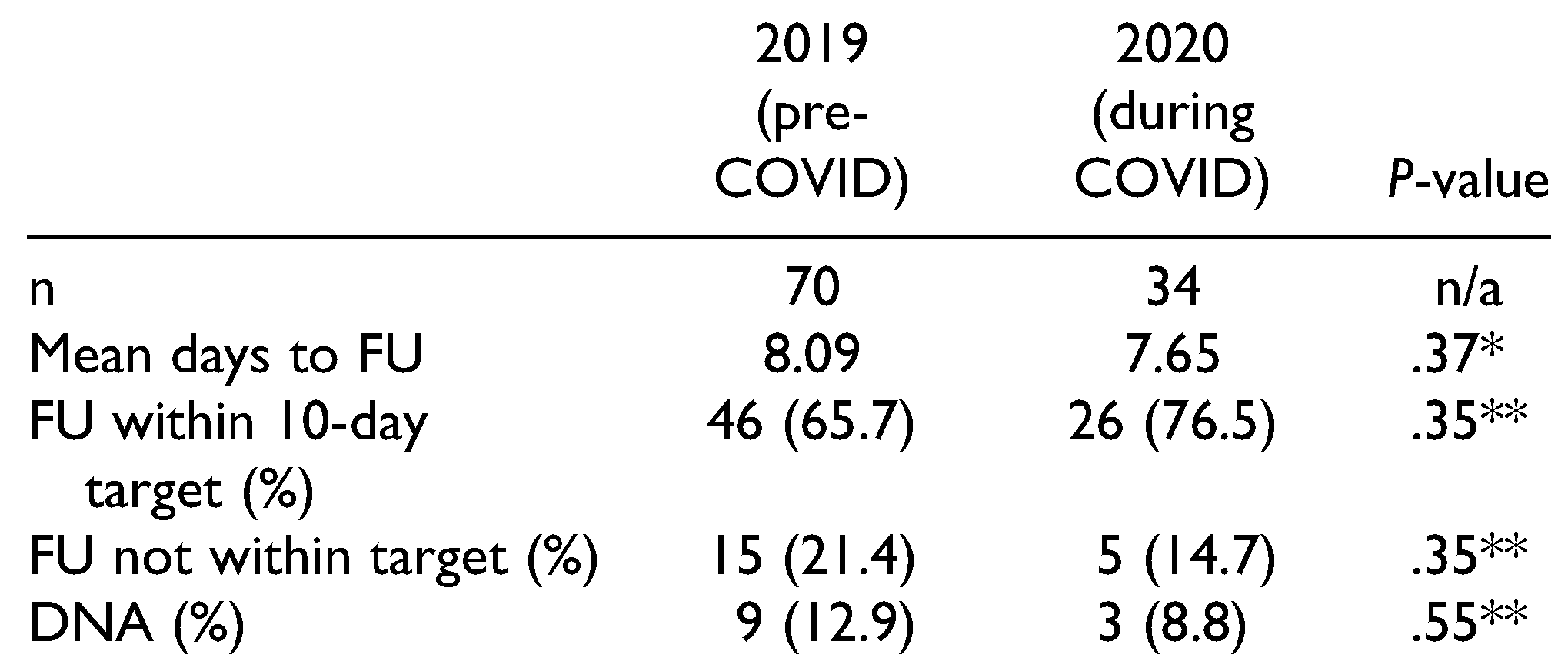

In the total patient cohort, the mean days to follow up was 8.00 days. The mean days to follow up in 2019 was 8.09 days and 7.65 days in 2020. This did not represent a statistically significant difference (

p = .37). In 2019, the number of patients seen within 10 days of initial injury was 46 (65.7%), with 15 patients not seen in this target (21.4%) and 9 DNAs (12.9%). In 2020, the number of patients seen within 10 days was 26 (76.5%), with 5 patients not seen in the target (14.7%), and 3 DNAs (8.8%). There was no statistically significant difference in the number of patients seen within 10 days of their initial injury between 2019 and 2020 (

p = .35), or the number of DNA patients (

p = .55). These findings are summarized in

Table 2.

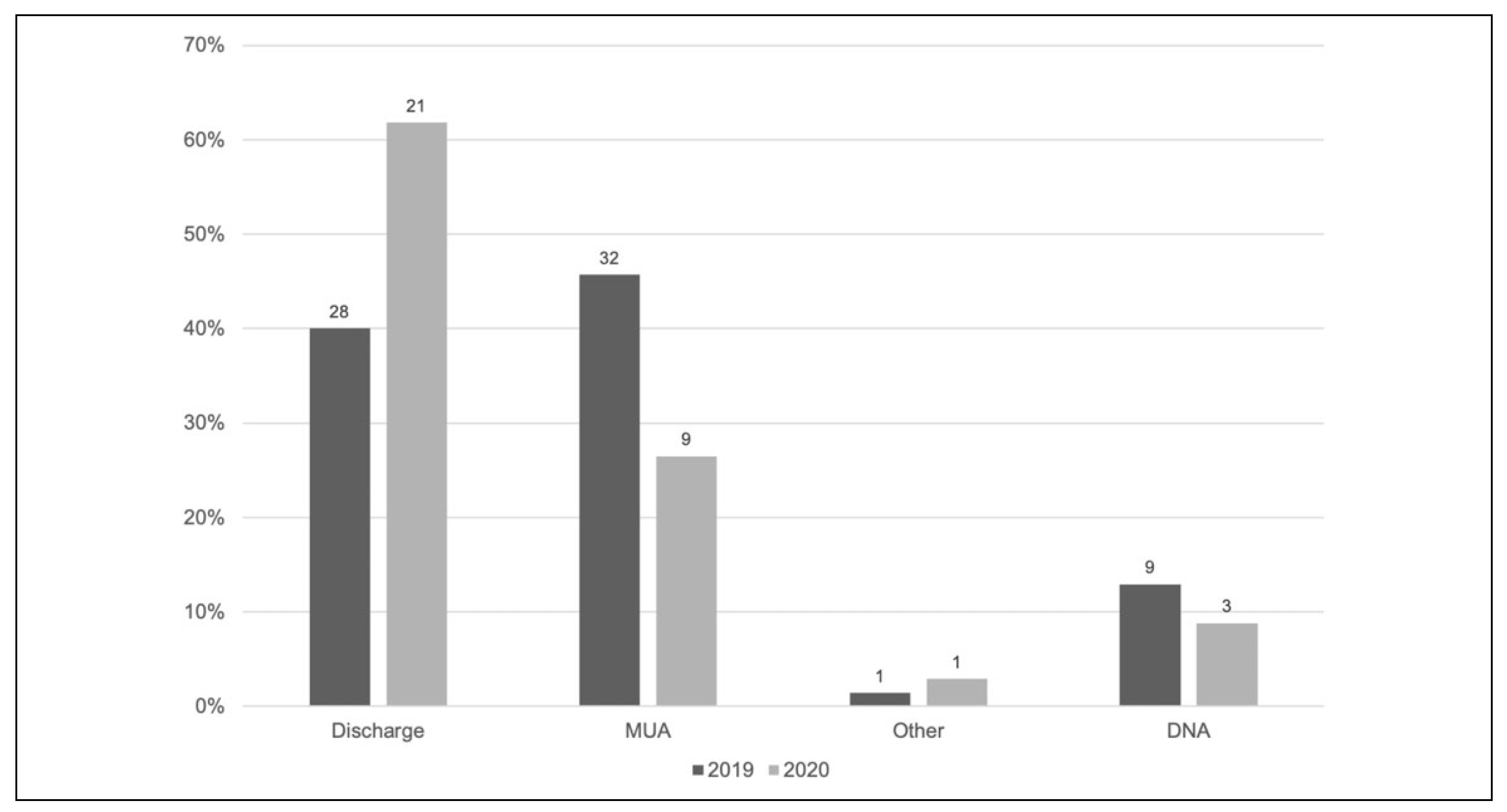

ENT Emergency Clinic Outcomes

In the whole cohort, the majority of ENT emergency clinic outcomes was patient discharge (i.e. no intervention performed) (n = 49, 47.0%). In 2019, the majority of patients were managed with an MUA (n = 32, 45.7%) with 28 patients discharged (40.0%), and 9 patients DNA (12.9%). The remaining patient was referred for rhinoplasty (1.4%). In 2020, the majority of patients were discharged (n = 21, 61.8%), with 9 requiring an MUA (26.5%) and 3 patients DNA (8.8%). The remaining patient required admission due to a septal hematoma (2.9%). This is summarized in

Figure 1.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand the impact of COVID on the management of nasal fractures at a MTC in the UK. We hypothesized that the number of nasal fracture patients would decrease during the period of the pandemic as a result of national lockdowns and social distancing measures. The specific aims were to quantify and analyze the frequency of nasal fractures and evaluation the time to follow up and management in ENT emergency clinics.

The results of this study confirm our hypothesis, showing a decrease in nasal fracture patients during the COVID pandemic at our center. There was a 51.4% reduction of patients being referred from ED for suspected or confirmed nasal bone fractures in 2020 compared to 2019. These findings are also in-keeping with other similar data sets that have demonstrated a reduction in overall ED admissions during this period.[

6,

25,

26] A recent study examined the effect of COVID on hospital admissions in Scotland and showed an overall reduction of 40.7% in ED attenders, 25.8% in emergency admissions and 60.9% in planned hospital admissions.[

5] Hampton et al showed a 53.7% reduction in orthopedic trauma admissions during the UK lockdown in week 14 of 2020 compared to the same time period in 2019.[

7] There have also been similar trends globally during comparable time periods with a reduced number of urgent surgical procedures performed in Italy[

27] and admissions for acute coronary syndromes in Austria.[

28]

There are a number of possible explanations for this. We know the most common cause of nasal fractures is blunt-force trauma secondary to RTAs, sports injuries or physical assault.[

11,

12] These require person activity and social interaction, which have been restricted as a result of national lockdowns and social distancing measures implemented throughout much of 2020 due to COVID. This was made clear when assessing Google mobility data (location data from Android mobile devices) in the UK showed a 63% reduction in overall movement in March 2020 compared to January 2020.[

29] It would therefore be reasonable to assume that these social restrictive policies are likely to reduce the incidence of accidents, assaults and other injuries. In addition, the government advised that road travel should restricted to essential trips, thereby reducing the number of potential vehicles to be involved in RTAs.

Furthermore, there was a shift in population health-seeking behavior, especially in the early stages of the pandemic. Members of the public may not have sought hospital care for fear of contracting COVID or believing that hospitals were too busy to deal with their ailments.[

5] As a result of this, the UK government launched a campaign to reassure the general public that the NHS remained open and urged people to seek medical attention should they feel they required it for non-COVID related conditions.[

30]

Our results also showed no significant difference in mean time to follow up of patients in ENT emergency clinic (2019 = 8.08 days vs. 2020 = 7.65 days, p = .37). This suggests that most patients were followed up in a timely manner in both years. However, on further examination, we would probably then expect more patients to be seen within the 10-day target in 2020 compared to 2019 due to a theoretical reduced emergency clinic burden in 2020. As the main referral point for the emergency clinic is from ED, it would logically follow that if there were a reduced number of overall ED admissions then we would expect to see a reduction in patients seen in emergency clinic. While there was a slight increase in the percentage of patients seen within the 10-day target (76.5% in 2020 vs. 65.7% in 2019), this was not a statistically significant difference (p = .35).

The reason for this is unclear but may be due to more referrals from primary care or other out-of-hours services (such as minor injury units, urgent care centers or walk-in-centers) that occupied slots in the emergency clinic. It may also be due to an increase in non-trauma related conditions managed in the emergency clinic such as otitis externa and sudden hearing loss. The proportion of patient’s DNA appointments also remained the same in both years (2019 = 12.9% vs. 2020 = 8.8%,

p = .55). This is likely due to numerous reasons affecting DNA rates that are unlikely to be affected by COVID, such as patient’s forgetting their appointments or and feeling that they no longer need to attend and clerical errors.[

31]

In terms of patient management and emergency clinic outcomes, there was a shift in the majority of patient’s being managed with an MUA in 2019 (45.7%) compared to being discharged in 2020 (61.8%). The rate of MUA decreased from 45.7% in 2019 to 26.5% in 2020. This may be explained by a change in severity of injury in 2020 as a result of increasing social distancing and reduced population movement leading to less high-velocity injuries. However, it may be due to a number of other factors that influence decisions for MUA such as patient preference.

This study is not without its limitations. There is a relatively small number of patients included which can reduce the power of our statistical analysis and subsequent validity of our results. Furthermore, retrospective study design carries pitfalls such as reliance on accurate record keeping which can impact data collection. There may have been patients missed through errors in hospital coding and retrieval which could have reduced a number of patients that should have been included.[

32] In addition, our study was only carried out at a single center which may reduce the applicability of our findings to other centers and areas. However, we have included all patients referred for suspected or confirmed nasal fracture presenting to ED from a MTC in a major city in the UK over a 2-year period. This is therefore likely to represent a good proportion of the trauma demographic in our city. Further studies could focus on a multi-center design to see if these findings are sustained across district general hospitals and non-trauma centers.

Our study builds on previous work that have assessed similar outcomes in different specialties and in ED and trauma admissions in general. It is therefore likely that the effect of COVID has hide a wide impact across many different patient groups. With a further UK lockdown announced on January 4, 2021, it remains to be seen how long COVID will influence healthcare and patients, and whether the effect on nasal fracture management in ENT emergency clinic will be sustained for another year.

Conclusion

Our study has shown that the number of patients seen in ENT emergency clinic for nasal fractures with a reduction in 51.4% from 2019 to 2020. This is likely secondary to a probable reduction in RTAs, sports injuries and physical assault as a result of lockdowns and social distancing measures introduced due to COVID in 2020. Despite this, there has been no significant change in average follow up time, the number of patients seen within 10-days or the number of DNA. The number of patients requiring an MUA has decreased from 45.7% in 2019 to 26.5% in 2020 which could be to numerous factors including patient preference. Our findings are in-keeping with other studies that have shown a reduction in ED attendances, trauma admissions and overall admissions across other specialties all around the world.