Pneumomediastinum as a Complication of Oral and Maxillofacial Injuries: Report of 3 Cases and a 50-Year Systematic Review of Case Reports

Abstract

:Introduction

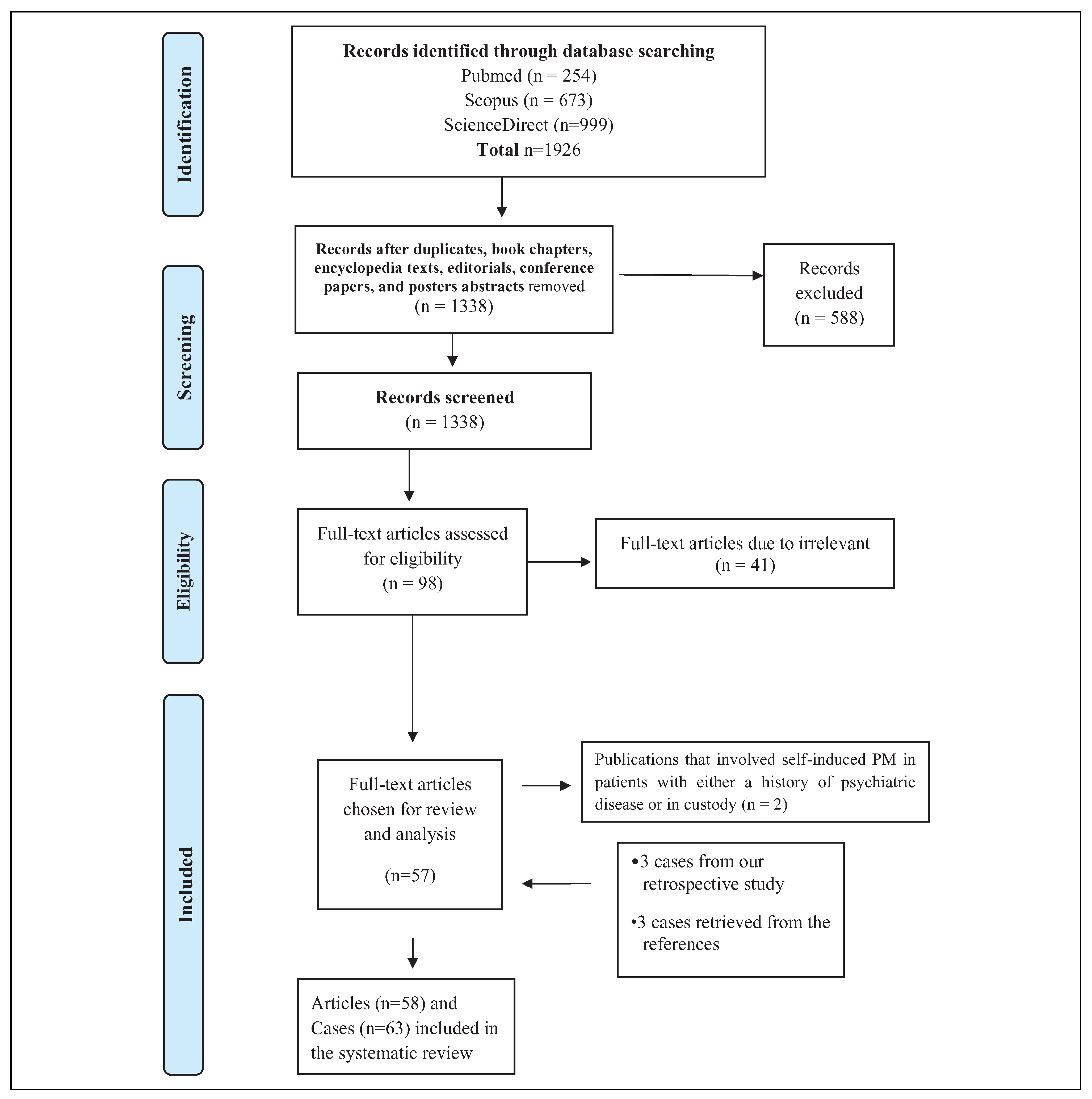

Material and Methods

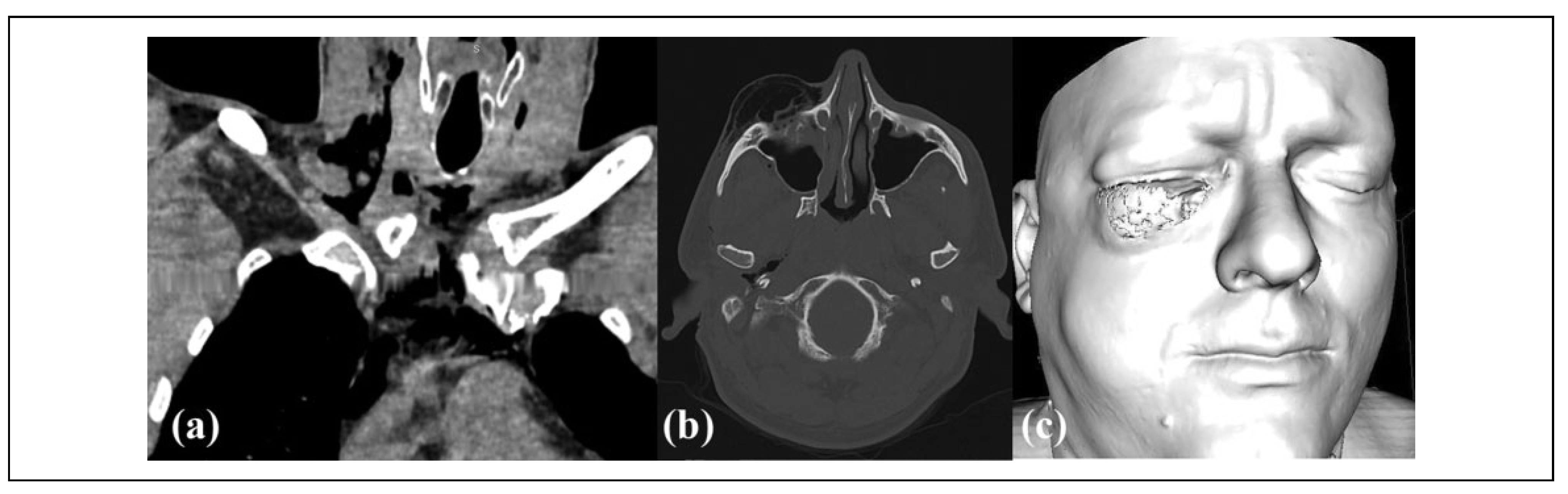

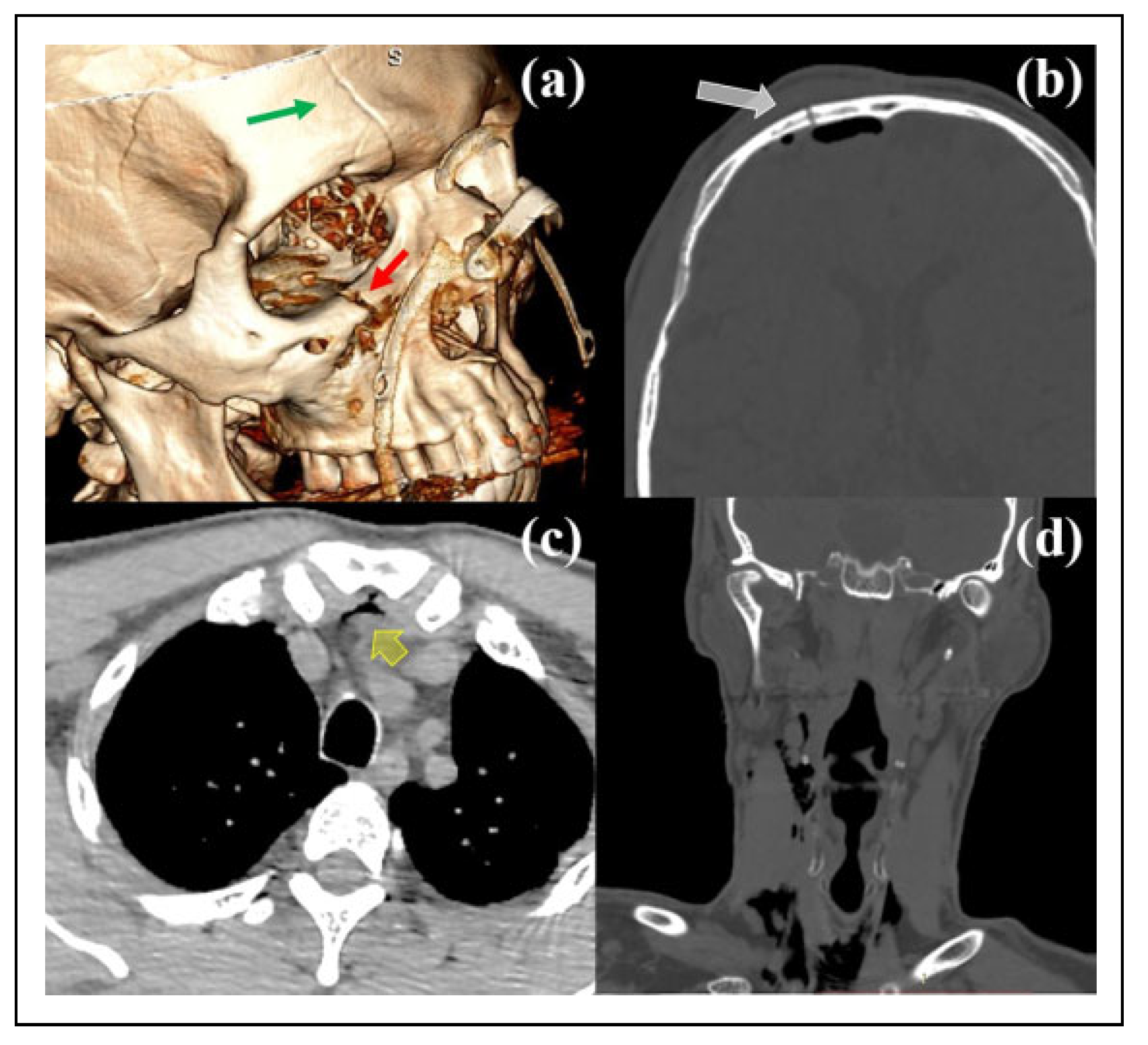

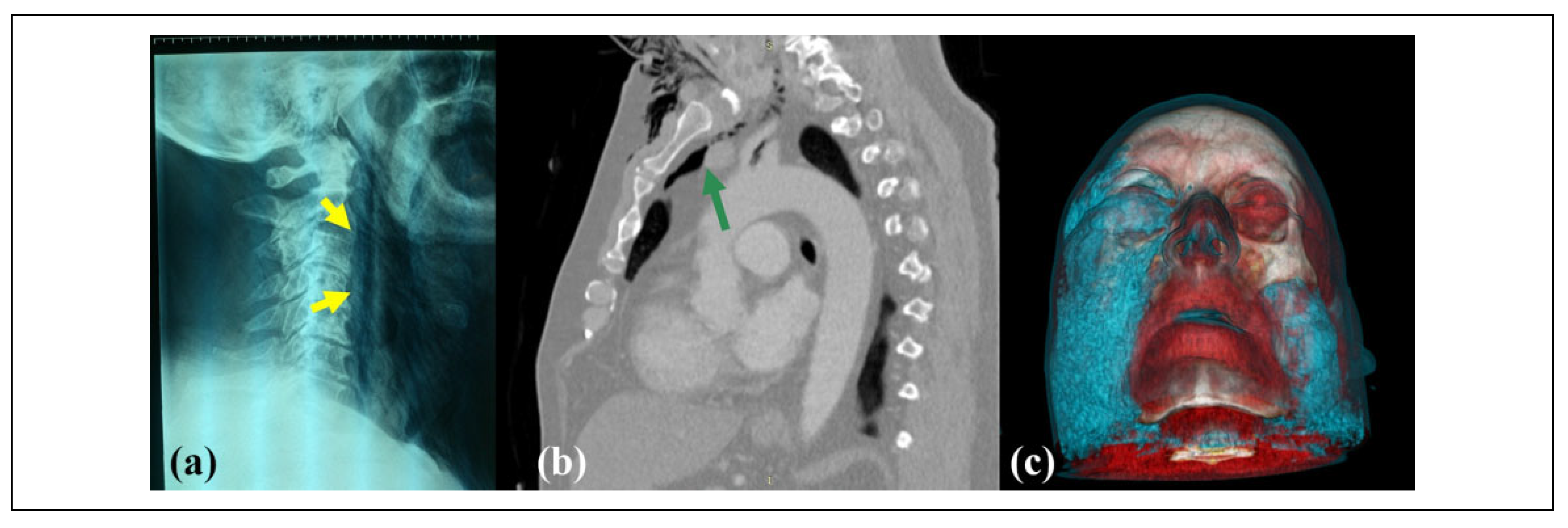

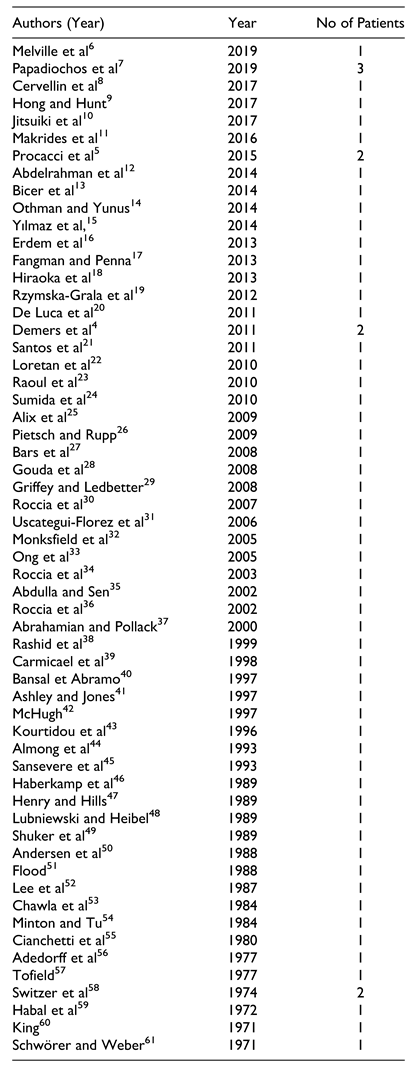

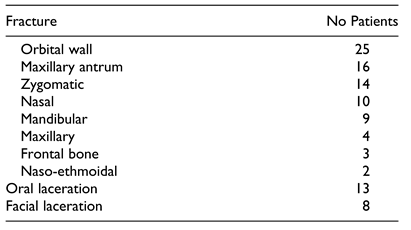

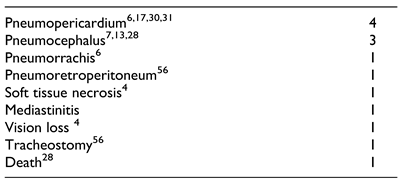

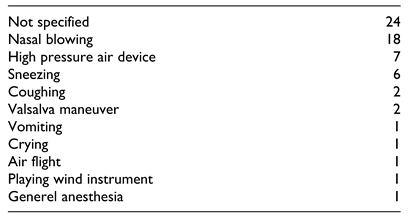

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lae¨nnec RTH. De l’auscultation mediate ou Traite du Diag- nostic des Maladies des Poumon et du Coeur, 1819.

- Baumann MH, Sahn SA. Hamman’s sign revisited. Pneu- mothorax or pneumomediastinum? Chest, 1281.

- Bickley, J. Hamman syndrome. Br J Hosp Med (Lond), 1: 77(03).

- Demers G, Camp JL, Bennett D. Pneumomediastinum caused by isolated oral-facial trauma. Am J Emerg Med, 8: 29(07).

- Procacci P, Zanette G, Nocini PF. Blunt maxillary fracture and cheek bite: two rare causes of traumatic pneumomedias- tinum. Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Melville JC, Balandran SS, Blackburn CP, Hanna IA. Massive self-induced subcutaneous cervicofacial, pneumo- mediastinum, and pneumopericardium emphysema sequelae to a nondisplaced maxillary wall fracture: a case report and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 1867. [CrossRef]

- Papadiochos I, Sarivalasis SE, Papadogeorgakis N. Acute hyponasality (closed rhinolalia) and craniomaxillofacial frac- ture suggest the coexistence of retropharyngeal emphysema and pneumomediastinum. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. [CrossRef]

- Cervellin G, Bellini C, Tarasconi S, Bresciani P, Lippi G. Massive pneumomediastinum following orbital fracture. Am J Emerg Med, 1585. [CrossRef]

- Hong B, Hunt P. Pneumomediastinum secondary to facial trauma. Am J Emerg Med. [CrossRef]

- Jitsuiki K, Hashimoto A, Yoshizawa T, Yanagawa Y. An infant case of intraoral penetrating injury with a toothbrush causing retropharyngeal and upper mediastinal emphysema. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. [CrossRef]

- Makrides H, Lawton LD. Don’t blow it! extensive subcuta- neous emphysema of the neck caused by isolated facial inju- ries: a case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman H, Shunni A, El-Menyar A, et al. Mediastinal emphysema following fracture of the orbital floor. J Surg Case Rep. 2014; 2014(5): rju032. Published May 2, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bic¸er YO¨, Kesgin S, Tezcan E, Ko¨ybas¸ı S. Facial, cervical, and mediastinal emphysema of the clarinet player: case report. Balkan Med J. [CrossRef]

- Othman MN, Yunus MRM. Cervicofacial emphysema: a rare presentation of a nasal bone fracture. Brunei Int Med J, 1: 10(3).

- Yılmaz F, C¸ iftc¸i O, O¨ zlem M, Komut E, Altunbilek E. Sub-cutaneous emphysema, pneumo-orbita and pneumomediasti- num following a facial trauma caused by a high-pressure car washer. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. [CrossRef]

- Erdem Y, Karatay M, Sertbas¸ I_, Celik H, Bayar MA. Air compressor-induced pneumocephalus, pneumomediastinum, and extensive emphysema. Pediatr Neurosurg.

- Fangman B, Penna KJ. Pneumomediastinum, pneumopericar- dium, orbital subcutaneous emphysema as consequence of low energy impact facial trauma. N Y State Dent J, 2: 78(6).

- Hiraoka T, Ogami T, Okamoto F, Oshika T. Compressed air blast injury with palpebral, orbital, facial, cervical, and mediastinal emphysema through an eyelid laceration: a case report and review of literature. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013; 13: 68. Published November 7, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzymska-Grala I, Palczewski P, Błaz_ M, Zmorzyn’ski M, Gołe˛biowski M, Wanyura H. A peculiar blow-out fracture of the inferior orbital wall complicated by extensive subcu- taneous emphysema: a case report and review of the litera- ture. Pol J Radiol. [CrossRef]

- De Luca G, Petteruti F, Tanga M, Luciano A, Lerro A. Pneu- momediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema unusual com- plications of blunt facial trauma. Indian J Surg. [CrossRef]

- Santos SE, Sawazaki R, Asprino L, de Moraes M, Fernandes Moreira RW. A rare case of mediastinal and cervical emphy- sema secondary mandibular angle fracture: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 2626. [CrossRef]

- Loretan S, Scolozzi P. Pneumomediastinum secondary to iso- lated orbital floor fracture. J Craniofac Surg, 1502. [CrossRef]

- Raoul G, Vanlergerghe B, Ferri J. Massive pneumomediasti- num and subcutaneous emphysema secondary to isolated zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture. J Craniofac Surg, 1316.

- Sumida T, Kobayashi A, Oka R, Yorozuya T, Nagaro T, Hamakawa H. Massive subcutaneous emphysema developing before surgery for mandibular fracture: a case report. Dent Traumatol.

- Alix T, Boutet C, Caquant L, Parrau G, Carlot B, Seguin P. Le pneumome’diastin, une complication rare d’une fracture mineure du maxillaire [Pneumomediastinum, a rare compli- cation secondary to a minor maxillary fracture]. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. [CrossRef]

- Pietsch C, Rupp P. Mediastinal emphysema after a simple maxillofacial fracture. Unfallchirurg.

- Bars N, Atlay Y, Tu¨ lay E, Tanju G. Extensive subcuta- neous emphysema and pneumomediastinum associated with blowout fracture of the medial orbital wall. J Trauma, 1366. [CrossRef]

- Gouda HS, Shashidhar D, Mestri C. Mediastinal emphysema due to an isolated facial trauma: a case report. Med Sci Law. [CrossRef]

- Griffey RT, Ledbetter S. Pneumomediastinum and subcuta- neous emphysema after isolated blunt facial trauma. J Trauma, 1201. [CrossRef]

- Roccia F, Diaspro A, Pecorari GC, Bosco G. Pneumomedias- tinum and cervical emphysema associated with mandibular fracture. J Trauma. [CrossRef]

- Uscategui-Florez T, Martinez-Devesa P, Gupta D. Mucosal tear in the oropharynx leading to pneumopericardium and pneumomediastinum: an unusual complication of blunt trauma to the face and neck. Surgeon. [CrossRef]

- Monksfield P, Whiteside O, Jaffe’ S, Steventon N, Milford C. Pneumomediastinum, an unusual complication of facial trauma. Ear Nose Throat J.

- Ong WC, Lim TC, Lim J, Sundar G. Cervicofacial, retro- pharyngeal and mediastinal emphysema: a complication of orbital fracture. Asian J Surg. [CrossRef]

- Roccia F, Griffa A, Nasi A, Baragiotta N. Severe subcuta- neous emphysema and pneumomediastinum associated with minor maxillofacial trauma. J Craniofac Surg. [CrossRef]

- Abdulla SR, Sen A. Mediastinal emphysema after a minor oral laceration. Emerg Med J. [CrossRef]

- Roccia F, Griffa A, Berardino M. Pneumomediastinum asso- ciated with cranio-maxillo-facial trauma. a case report. Riv Ital Chir Maxillo-Facciale.

- Abrahamian FM, Pollack CV. Traumatic pneumomediasti- num caused by isolated blunt facial trauma: a case report. J Emerg Med. [CrossRef]

- Rashid MA, Wikstro¨m T, Ortenwall P. Pneumomediastinum after nasal fracture. Eur J Surg.

- Carmichael F, Ward-Booth RP, Banks JM. Pneumomediasti- num after facial trauma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. [CrossRef]

- Bansal BC, Abramo TJ. Subcutaneous emphysema as an uncommon presentation of child abuse. Am J Emerg Med.

- Ashley M, Jones C. Pneumomediastinum: an unusual radio- graphic finding following mid-facial trauma injury. Injury. [CrossRef]

- McHugh, TP. Pneumomediastinum following penetrating oral trauma. Pediatr Emerg Care. [CrossRef]

- Kourtidou-Papadeli C, Paspatis A, Mohler S. Pneumomedias- tinum during flight secondary to facial fractures—a case report. Aviat Space Environ Med, 1201.

- Almog Y, Mayron Y, Weiss J, Lazar M, Avrahami E. Pneu- momediastinum following blowout fracture of the medial orbital wall: a case report. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg.

- Sansevere JJ, Badwal RS, Najjar TA. Cervical and mediast- inal emphysema secondary to mandible fracture: case report and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 2: 22(5). [CrossRef]

- Haberkamp TJ, Levine HL, O’Brien G. Pneumomediastinum secondary to a mandible fracture. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. [CrossRef]

- Henry CH, Hills EC. Traumatic emphysema of the head, neck, and mediastinum associated with maxillofacial trauma:case report and review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

- Lubniewski AJ, Feibel RM. Traumatic air blast injury with intracranial, bilateral orbital, and mediastinal air. Ophthalmic, 1989.

- Shuker S, Hirmiz NH, Abd al-Sada RS. Pneumomediastinum and cervical emphysema subsequent to mandibular injury associated with a flare pistol shot. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. [CrossRef]

- Andersen C, Andersen C, 2ndRasmussen F.Pneumomedias- tinum associated with orbital fracture. Case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. [CrossRef]

- Flood, TR. Mediastinal emphysema complicating a zygomatic fracture: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. [CrossRef]

- Lee HY, Samit A, Mashberg A. Extensive post-traumatic subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum follow- ing a minor facial injury. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. [CrossRef]

- Chawla K, Steinbaum S, Alexander LL. Pneumomediastinum occurring in association with facial trauma. N Y State J Med.

- Minton G, Tu HK. Pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and cervical emphysema following mandibular fractures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. [CrossRef]

- Cianchetti JA, Carroll GF. Traumatic pneumomediastinum resulting from facial trauma. Ann Emerg Med.

- Adendorff D, Malherbe WD, Grotepass F. Generalized surgical emphysema as an early complication of facial frac- ture: a case report. S Afr Med J.

- Tofield, JJ. Pneumomediastinum following fracture of the maxillary antrum. Br J Plast Surg.

- Switzer P, Pitman RG, Fleming JP. Pneumomediastinum associated with zygomatico-maxillary fracture. J Can Assoc Radiol.

- Habal MB, Beart R, Murray JE. Mediastinal emphysema sec- ondary to fracture of orbital floor. Am J Surg.

- King, YY. Ocular changes following air-blast injury. Arch Ophthalmol.

- Schwo¨ rer J, Weber P. Mediastinalemphysem nach Fraktur im Bereich der Nasennebenho¨hlen [Mediastinal emphysema following fracture in the region of the paranasal sinuses]. Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Nuklearmed.

- Brasileiro BF, Cortez AL, Asprino L, Passeri LA, De Moraes M, Mazzonetto R,... Moreira RW. Traumatic subcutaneous emphysema of the face associated with paranasal sinus frac- tures: a prospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 1: 63(8), 1080.

- van Issum C, Courvoisier DS, Scolozzi P. Posttraumatic orbi- tal emphysema: incidence, topographic classification and possible pathophysiologic mechanisms. A retrospective study of 137 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol.

- Bejvan SM, Godwin JD. Pneumomediastinum: old signs and new signs. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 1041.

- Ahmed Y, Ng M. Extensive Cervicomediastinal emphysema from mastoid injury. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. [CrossRef]

- Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, et al. Spontaneous pneumome- diastinum: 41 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg, 1110.

- Von Arx DP, Gilhooly M. An unusual presentation of orbital floor fracture. Br J Oral Surg.

- Kouritas VK, Papagiannopoulos K, Lazaridis G, et al. Pneu- momediastinum. J Thorac Dis, S: 1).

- Sahni S, Verma S, Grullon J, Esquire A, Patel P, Talwar A. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: time for consensus. N Am J Med Sci.

- Gerazounis M, Athanassiadi K, Kalantzi N, Moustardas M. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a rare benign entity. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.

- Perna V, Vila` E, Guelbenzu JJ, Amat I. Pneumomediastinum: is this really a benign entity? When it can be considered as spontaneous? Our experience in 47 adult patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg.

- von Bergen V, Dissanaike S, Jurkovich GJ. Pneumomedias- tinum in blunt trauma: a review. Trauma.

- Hoover LR, Febinger DL, Tripp HF. Rhinolalia: an under- appreciated sign of pneumomediastinum. Ann Thorac Surg.

- Dalston RM, Warren DW, Dalston ET. The identification of nasal obstruction through clinical judgments of hyponasality and nasometric assessment of speech acoustics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop.

- Clarke R, McMahon SD. Disorders of speech. In: Gleeson M, Clarke RW, ed. Scott-Brown’s Otolaryngology, 2: 2008; 99, 2008.

- Kirchner JA: Cervical mediastinal emphysema. Arch Otolar- yngol.

- Kaneki T, Kubo K, Kawashima A, Koizumi T, Sekiguchi M, Sone S. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in 33 patients: yield of chest computed tomography for the diagnosis of the mild type. Respiration.

- Oliver AJ, Diaz EM, JrHelfrick JF. Air emphysema secondary to mandibular fracture: case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 1143.

- Demas PN, Braun TW. Infection associated with orbital sub- cutaneous emphysema. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 1239.

- Munsell, WP. Pneumomediastinum: a report of 28 cases and review of the literature. JAMA.

- Anderson JA, Tucker MR, Foley WL, Pillsbury HC, 3rd Norfleet EA. Subcutaneous emphysema producing airway compromise after anesthesia for reduction of a mandibular fracture. A case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol.

- Kramer NR, Fine MD, McRae RG, Millman RP. Unusual complication of nasal CPAP: subcutaneous emphysema fol- lowing facial trauma. Sleep.

- Beltran GW, Lopez MD. Fifty-year-old female with facial subcutaneous emphysema: a case report. Am J Emerg Med.

- Linberg, JV. Orbital emphysema complicated by acute central retinal artery occlusion: case report and treatment. Ann Ophthalmol.

- Hunts JH, Patrinely JR, Holds JB, Anderson RL. Orbital emphysema. Staging and acute management. Ophthalmol- ogy.

- Reading, P. Autemphysesis. Br Med J. 1950;1(4645):105. [CrossRef]

- Mart’ınez-Carpio PA, del Campillo A’ F, Leal MJ, Lleopart N, Marro’n MT, Trelles MA. Camouflaging facial emphysema: a new syndrome. Forensic Sci Int. [CrossRef]

- Lo’pez-Pela’ez MF, Rolda’n J, Mateo S.Cervical emphysema, pneumomediastinum, and pneumothorax following self-induced oral injury. Report of four cases and review of the literature. Chest.

- Holland TE, Smith DM, Gibson GN, Brinkerhoff JG. Water balloon-induced orbital fracture in an aviator. Mil Med Res.

- Mahmood S, Keith DJW, Lello GE. When can patients blow their nose and fly after treatment for fractures of zygomatic complex: the need for a consensus. Injury.

- Seiff, SR. Perspective: atmospheric pressure changes and the orbit: recommendations for patients after orbital trauma or surgery. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg.

- Tan-Gore E, Thanigaivel R, Wilson B, Thomas A, Thomas ME. Flying and midface fractures: the truth is out there. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 1506.

- Ye Q, Hang LZ, Ian XT, Hi JS. Exacerbation of pneumome- diastinum after air travel in a patient with dermatomyositis. Aviat Space Environ Med.

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the AO Foundation. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papadiochos, I.; Sarivalasis, S.-E.; Chen, M.; Goutzanis, L.; Kalyvas, A. Pneumomediastinum as a Complication of Oral and Maxillofacial Injuries: Report of 3 Cases and a 50-Year Systematic Review of Case Reports. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2022, 15, 72-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387521997236

Papadiochos I, Sarivalasis S-E, Chen M, Goutzanis L, Kalyvas A. Pneumomediastinum as a Complication of Oral and Maxillofacial Injuries: Report of 3 Cases and a 50-Year Systematic Review of Case Reports. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2022; 15(1):72-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387521997236

Chicago/Turabian StylePapadiochos, Ioannis (Yiannis), Stavros-Evangelos Sarivalasis, Meg Chen, Lampros Goutzanis, and Aristotelis Kalyvas. 2022. "Pneumomediastinum as a Complication of Oral and Maxillofacial Injuries: Report of 3 Cases and a 50-Year Systematic Review of Case Reports" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 15, no. 1: 72-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387521997236

APA StylePapadiochos, I., Sarivalasis, S.-E., Chen, M., Goutzanis, L., & Kalyvas, A. (2022). Pneumomediastinum as a Complication of Oral and Maxillofacial Injuries: Report of 3 Cases and a 50-Year Systematic Review of Case Reports. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 15(1), 72-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387521997236