Introduction

Rhinophyma is a disfiguring overgrowth of sebaceous glands in the nasal tissue that has been associated with severe nasal obstruction and undesirable cosmetic implications. Previous studies demonstrate that rhinophyma represents the most severe stage of acne rosacea.[1] The disease process is associated with unregulated superficial vasodilation, chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and hyperplasia of the nasal tissue.[2] Despite acne rosacea occurring at a ratio of 3 females to 1 male, rhinophyma occurs almost exclusively in men, with a male-to-female ratio of 12:1 to 30:1, and most commonly develops during the fifth to seventh decades of life. Additionally, this condition predominantly affects the Caucasian population.[2,3] While the etiology of rhinophyma is not fully understood, it is thought that hormonal factors, specifically increased androgens in men, play a role in its development.[4] In addition to this androgenic influence, the skin mite Demodex folliculorum has been elucidated as a contributing factor in the progression of rosacea to rhinophyma.[5] Alcohol use, damage by heat or cold, gastrointestinal disease, and disturbances in fat metabolism have also been implicated in aggravating the disease.[2,4]

Clinically, rhinophyma is characterized by hyperplasia of dermal and sebaceous glands, dilated and cystic sebaceous ducts, and telangiectasias.[6,7,8] The nose is often erythematous and may display textural changes including pits, fissures, and scarring. Rhinophyma preferentially affects the tip of the nose, and the dorsum, alae and side walls to a lesser extent. As the nasal skin hypertrophies, the aesthetic subunits of the nose are distorted, merged, and obliterated and excess growth often causing secondary nasal obstruction.[4,6] El-Azhary et al 1991 developed a grading system to classify the severity of rhinophyma into minor, moderate, or major rhinophyma.[9] Minor rhinophyma is characterized by telangiectasia and mild thickening or textural changes. Moderate is characterized by skin thickening and the presence of lobules, and finally, major (severe) rhinophyma is characterized by nasal hypertrophy and prominent lobules. As the nasal skin hypertrophies, this excess tissue can obstruct the nasal valves, causing respiratory complications as well as eating difficulties.[4,10] Rhinophyma can also present as a serious cosmetic concern for patients, causing significant psychosocial stress, anxiety, and impairment of personal and profession life resulting in isolation and stigmatization of the person.[2,11] Facial disfigurement of similar severity is well known to predispose patients to depression and social phobia, in some cases resulting in complete social isolation.[12,13]

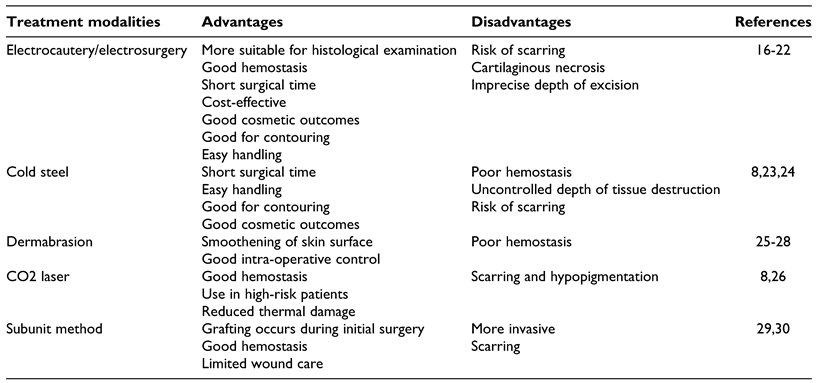

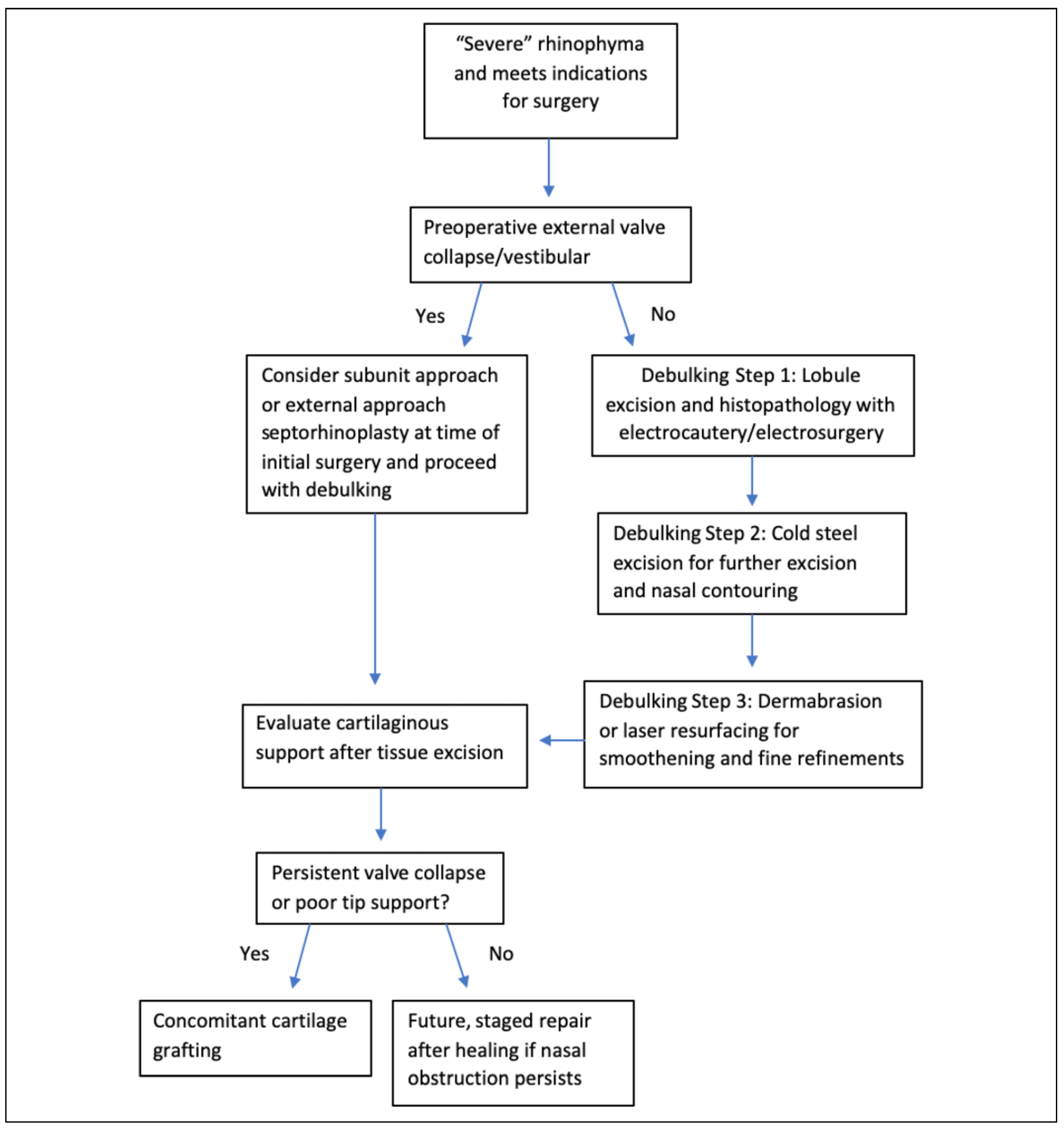

While more mild-to-moderate cases can often be managed in the clinic or outpatient setting, major or severe rhinophyma, must be managed with formal operative intervention to adequately address obstruction and nasal contour deformity. Surgical intervention is often performed in 2 stages: (1) surgical planning of rhinophyma, which involves removal of the excess nasal tissue, and (2) reconstruction and relief of nasal obstruction, representing the functional repair stage of treatment. There are multiple techniques used in the surgical planning of rhinophyma, and decision-making on which technique to use is typically based on the surgeon’s preference, as there is no current consensus or gold standard of therapy. Current operative techniques include cold steel, loop electrocautery, dermabrasion, and laser ablation.[14] Often times various combinations of these techniques are utilized, and an individualized approach is necessary.

The objective of our study is to systematically review current techniques used in the surgical management of severe rhinophyma, demonstrate the strengths and pitfalls of each method, and illustrate the expected functional and cosmetic outcomes of surgical intervention. Our goal is to provide a treatment algorithm to inform decision-making of surgical approaches to address treatment of severe rhinophyma.

Discussion

Electrosurgery and Electrocautery

Electrosurgery and electrocautery are widely favored by dermatologic and facial plastic surgeons in the treatment of rhinophyma. While these 2 terms often get used interchangeably, there are subtle differences that should set them apart from one another. Electrosurgery, on the one hand, uses radiofrequency electricity to generate heat in the tissue itself. On the other hand, electrocautery describes application of heat to the tissue from an outside source. A benefit of these surgical modalities is that the excised tissue pieces can be more suitable for histological examination, potentially revealing any underlying malignancies. Histopathology may be difficult with other surgical modalities for excision of rhinophyma, such as CO2 laser, due to immediate tissue destruction.[16]

Rørdam and Guldbakke conducted a case series to examine the treatment of rhinophyma using electrosurgery with a wire loop.[17] All patients had moderate-to-large rhinophyma previously treated medically with antibiotics, steroids, and retinoids as well as cryotherapy and pulsed dye laser without effect. Surgery was performed with an electrosurgical monopolar wire loop at 80 W “cut/coagulate mode,” and bleeding spots were coagulated using monopolar electrocautery. Cutaneous re-epithelialization occurred within 3 weeks for all patients with residual erythema lasting 4 to 8 weeks.[17] Similarly, Somogyvári and colleagues observed a 2.5-week period to re-epithelialization in their case series using 28 W “cut/coagulate mode” loop cautery.[16] Marcasciano et al reported 2-to-3-week healing times in their case series of 10 patients treated with electrocautery for moderate-to-severe rhinophyma.[18] Additionally, 3 case studies discussing treatment of severe rhinophyma with electrocautery reported re-epithelialization times between 2 and 4 weeks.[19,20,31] All studies reported good hemostasis and the added benefits of short surgical times and cost-effectiveness.[16−18,20,21]

In González et al case series of 7 patients with severe rhinophyma treated with electrosurgery, 3 patients presented postoperatively with obvious scarring and 2 presented with persistent erythema.[21] The case studies by Prado et al and Husein-ElAhmed and Armijo-Lozano both demonstrated mild nasal tip scarring a few months post-operatively, but these patients were still very satisfied with their cosmetic outcomes.[19,20] The other studies did not report postoperative complications including wound infection, scarring, hypopigmentation, or prolonged erythema.[16,17,18]

The case study by Wolter et al highlights the long-term sequelae of poor nasal breathing as a consequence of severe rhinophyma. They examined a 65-year-old male with a long-standing history of rhinophyma causing total nasal obstruction requiring tracheotomy, and recurrent pneumonia from bacterial colonization of the sebaceous pits of the rhinophyma. He underwent surgical intervention with wire loop electrocautery. He was successfully decannulated from the tracheotomy 1 week post-operatively, his breathing was restored to normal, and he did not have any complications. They discuss the ability to preserve the alar cartilage and deep pilosebaceous tissue with the use of electrocautery, which allows for recreation of the aesthetic subunits of the nose.[31] However, due to the intense heat generated during excision with electrocautery, there is an added risk of damage to the underlying cartilaginous structure, potentially prolonging scarring or necrosis.[32,33]

Somogyvári et al reported Visual Analog Scores (VAS) on a scale of 1-10 to objectively rate cosmetic appearances preoperatively to 3 months postoperatively for patients treated with electrosurgical excision of rhinophyma. The preoperative VAS mean was 1, while the postsurgical mean was 6.5, indicating significant improvement in cosmesis.[16] The case series by Greaney et al reported a mean VAS of 7.5 postoperatively with the use of scalpel excision compared to a mean of 1.0 preoperatively.[23] Despite this slight postoperative cosmetic improvement with scalpel excision compared to electrosurgery, Greaney et al did not indicate the length of time in the postoperative period before repeat VAS were assessed. The higher postoperative scores with scalpel excision could indicate better cosmetic outcomes with this surgical modality but could also be attributed to differences in severity of rhinophyma of the study subjects, other patient characteristics, or surgeon experience with the specific surgical technique.

Götkay et al performed a case series of 13 patients treated with high-frequency electrosurgery and utilized the novel rhinophyma severity index (RHISI), originally developed by Wetzig et al, to assess cosmetic outcomes in the postoperative follow-up period.[22,34] The RHISI constitutes 3 blinded dermatologists classifying rhinophyma severity on the basis of standard pre- and postoperative photos in random sequence, with a higher RHISI indicating greater severity of disease.[34] Götkay et al reported RHISI scores at 3 follow-up visits within an average period of 22-months following initial surgery. Significantly lower RHISI scores were reported at each respective follow-up visit compared to preoperative scores for all patients. Similarly, 21 patients (91%) showed improved RHISI scores at follow-up within an average of 37 months postoperatively in Wetzig et al study of outcomes among 23 patients treated with scalpel excision. In terms of complications, Götkay et al reported no uncontrollable bleeding, infection, or postoperative pain with electrosurgery, however 23% (N = 3) did experience slight hypertrophy in the surgical area.[22] This is markedly less than the 47% (N = 11) of patients treated with scalpel excision for whom Wetzig et al reported slow recurrence and hypertrophy over time.[34] Therefore, this may indicate that electrocautery potentially may be associated with better long-term disease remission periods compared to scalpel excision.

Electrocautery and cold steel may be used in combination for treatment of severe rhinophyma, as examined in the Prado et al and Husein-ElAhmed and Armijo-Lozano case studies. Both studies discussed the use of scalpel excision for initial debulking of the rhinophymatous tissue followed by wire loop electrocautery for contouring, demonstrating good postoperative functional and cosmetic outcomes.[19,20] For wire loop electrocautery, Prado et al explained that care was taken to decrease the wire loop current from 6 on the nasal sidewall and dorsum to 4 on the tip and ala to minimize the risk of cartilage damage.[19] The use of electrocautery as a single treatment modality or in combination with cold steel demonstrates comparable outcomes, indicating that treatment decision-making to utilize 1 surgical option versus multiple may ultimately depend on the extent of disease and nasal obstruction, quality of hemostasis, etc.

Cold Steel

Cold steel excision in the treatment of severe rhinophyma is a widely favored technique due to the ability to quickly debulk the excess diseased tissue. The goal of scalpel excision is ultimately superficial decortication, or partial excision, of the hypertrophic tissue with retainment of the pilosebaceous tissue, which then serves as the layer allowing for subsequent re-epithelialization. Greaney et al describes a case series of treating 7 patients with moderate-to-severe rhinophyma using a 10-blade scalpel to primarily debulk the nose, followed by a standard retail disposable, plastic-handled safety razor to achieve fine contouring.[23] The average duration of surgery was 40 minutes, which is comparable to that of electrosurgery.[16,23] One subject had mild postoperative bleeding which resolved spontaneously without intervention, no patients required subsequent surgical revisions, and all patients were satisfied with their results.[23] A Lazzeri et al case study of a 62-year-old male with severe rhinophyma causing nasal obstruction discussed their technique in excising the rhinophymatous tissue. The scalpel is used to initially debulk the more obviously thickened sebaceous tissue, followed by stabilization of the dome by inserting a fingertip into the nostril and using the scalpel to sculpt the remaining thickened skin. Ultimately the goal is to preserve the nasal osteocartilaginous framework to prevent external valve collapse postoperatively and to maintain appropriate contouring for aesthetically pleasing results.[24]

Lazzeri et al reviewed the long-term results of 67 patients affected by rhinophyma treated with either tangential excision (N = 45) or CO2 laser (N = 22). The tangential excision method involved debulking of the rhinophymatous tissue with a 10-blade scalpel combined with fine bipolar diathermy to cauterize bleeding vessels, as well as mild dermabrasion to achieve final shaping results.[8] Both Greaney et al and Lazzeri et al reported the benefits of scalpel excision to be the ease and quickness of the procedure and satisfying cosmetic results.[8,23] Lazzeri et al reported spontaneous re-epithelialization occurring as early as 6 days after treatment and occurring for all patients within 1 month, which is generally similar to the 2-3-week healing times reported with the use of electrocautery.[8,16,18] Several case studies discuss the re-epithelialization and complete healing times for their respective patients. These periods ranged from re-epithelialization occurring at 2 weeks and complete healing at 4 weeks,[35] to re-epithelialization at 4 weeks and complete healing at 2 months.[36,37] This variation could be largely dependent on the extent of disease and how deeply the tissue is excised.

Lazzeri et al reported that overall, 92.5% of patients had an “excellent” self-impression with tangential excision, and 75% felt that the time to return back to social life was “sufficient” and 17.5% felt that this time was “quick.” On the other hand, the majority of patients in the CO2 laser group reported that return back to social life was “long” (78.9%),[8] indicating that healing time may be prolonged with use of CO2 laser compared to cold steel.

Wójcicka et al performed a case study of a 69-year-old male with giant rhinophyma causing airway obstruction and difficulty eating. They compare the use of partial-thickness tangential excision using cold steel to full-thickness excision and reconstruction with flaps or skin grafts. They concluded that partial-thickness excision allows for better healing and more positive aesthetic results but may be associated with higher recurrence rates as not all of the rhinophymatous tissue may be excised. However, full-thickness excision with full-thickness skin grafting can be useful for deeply infiltrating rhinophyma or disease with underlying neoplasia.[38]

A disadvantage of scalpel excision as noted by Lazzeri et al was excessive intra-operative blood loss that slowed down some procedures by obscuring the operating field, which could lead to imprecise removal of tissue, and thus poor cosmetic results. This disadvantage contributed to 3 cases of residual scarring of the ala, dorsum of the nose, and tip, respectively.[8] To avoid such complications of excess bleeding with scalpel excision, bipolar electrocautery could be used for hemostasis,[37] or epinephrine-soaked gauze can be placed on the area of the nose, thus avoiding the risk of eschar formation or scarring that may occur with use of cauterization.[8]

Dermabrasion

Dermabrasion is an exfoliating technique that utilizes a rotating instrument to remove outer layers of skin. This technique can cause extensive bleeding and consequently poor visualization of the surgical field,[25] and thus is less often reported as being used as the sole modality for treating rhinophyma. It is most commonly used after initial debulking of excess rhinophymatous tissue to smoothen the skin surface.[25,26,32] Hom and Harmon discuss the use of wire loop electrocautery and dermabrasion in the excision and contour of rhinophyma. They discuss the diamond fraise and wire brush varieties of dermabraders, specifically highlighting the advantages of the diamond fraise tip as the preference of the authors. The diamond fraise allows the surgeon to choose from a variety of tip sizes, shapes, and stone grade coarseness according to the area requiring contouring as well as operator’s preferences. Another advantage is that it provides more control when removing dermal layers such that anatomical depth assessment can be made accurately.[32]

Clarós et al conducted a case series of 12 patients with rhinophyma for whom the same therapeutic approach was used, consisting of dermabrasion, decortication, and application of fibrin glue on the skin surface to promote complete healing.[27] They used both diamond and wire brush dermabrasion depending on location and size of the area requiring contouring. This simple technique was shown to ensure good hemostasis, rapid epithelialization of the wound, and good cosmetic results. However, this case series did not specify the length of time to re-epithelialization or patient satisfaction ratings with their technique.

Chellappan and Castro’s case report of a 62-year-old male with nasal obstruction and major cosmetic deformity discusses the use of wire loop electrocautery and dermabrasion for smooth contouring. The patient had normal skin pigmentation at 4-week follow-up and significant improvement in breathing. They conclude that electrocautery plus dermabrasion allows for sufficient contouring and smoothening, efficient hemostasis, more control in the operating room, and does not require multiple surgeries.[28] However, the need for future procedures is dependent on patient satisfaction with the initial outcomes, disease recurrence, and extend of nasal obstruction possibly requiring reconstruction for functional improvement. Ferneini et al presented a case report of a 66-year-old male with severe rhinophyma of the nasal tip with impaired breathing surgically treated with a combination cold steel and dermabrasion. The lesion was excised with a 10-blade scalpel and further excision and fine contouring were achieved with the dermabrader. They had good hemostasis, restoration of the nasal contour, and reported only mild scarring of the nasal tip postoperatively.[39] The similar cosmetic and functional outcomes in these case studies may indicate that neither electrocautery nor cold steel is superior as the adjunct modality to dermabrasion in the surgical treatment of rhinophyma. Since dermabrasion is most commonly used in conjunction with other operative techniques, we are unable to directly compare the postoperative characteristics of dermabrasion relative to other surgical approaches.

CO2 Laser

Laser surgery represents a newer treatment option for patients with rhinophyma. The CO2 laser creates a wavelength of 10,600 nm and is characterized by its high affinity to water. As skin contains a very high percentage of water, there is an almost complete absorption by the skin and mucosa with an efficient carbonization effect. For the 22 patients treated with CO2 laser in the Lazzeri et al comparative study of tangential excision and CO2 laser, the laser was used freehand in continuous cutting mode to debulk excess tissue in severe rhinophyma. Fine sculpting of the nasal contour was established by using the resurfacing or low-energy continuous mode on the laser. Back and forth motion of the laser close to the nose allowed for tissue vaporization of the major bulk and hemostasis resulting in a black eschar that could be wiped off with sterile gauze.[8]

The benefit of this treatment modality is control of hemostasis, providing a bloodless operative field. However, patients treated with CO2 laser were more likely to have prolonged postoperative erythema compared to the tangential excision group. Also, there was 1 case of scar contraction and 1 case of hypopigmentation in the CO2 laser group, while no hypertrophic scarring, pain, bleeding, and hypopigmentation were observed with tangential excision. Such postoperative complications with the CO2 laser may be attributed to the deep tissue penetration with the laser, causing damage to the dermis and adnexa, thus increasing scar risk.[8] However, this can also be a complication of scalpel excision, and therefore other pros and cons of each surgical modality must be weighed in deciding which technique to use. The Hofmann and Lehmann review of treatment modalities for various stages of rosacea discusses therapeutic options for phymatous changes as secondary features of rosacea.[26] They similarly report postoperative complications of scarring and hypopigmentation with CO2 laser, as well as the benefit of its coagulative effects. Additionally, the rhinophyma treatment review by Fink et al highlights these same advantages and disadvantages, and concludes that the overall risks of surgical excision and CO2 laser are comparable.[33]

Tortorella et al highlights other advantages of the CO2 laser in their case of a 76-year-old male who benefited greatly from the availability of this surgical modality. This patient suffered from a large rhinophyma for several years causing respiratory function and social life to worsen. He was taking an anticoagulant for a previous aortic valve replacement and placement of a bicameral pacemaker. He also showed several comorbidities such as hypertension and metabolic syndrome. His high risk of uncontrolled bleeding and multiple comorbidities impeded any type of surgery approach for rhinophyma treatment, and for these reasons he underwent treatment with CO2 laser without cessation of anticoagulant therapy. They demonstrate the advantages of use in high-risk patients, infrequent need for anesthesia, reduced thermal damage compared to electrocautery, and decreased bleeding and inflammation.[40] However, this case study does not address potential postoperative complications and time to complete healing. While there are many benefits of the CO2 laser, it is ultimately less-commonly used compared to other modalities due to its high expense, prolonged operative time, and specialized training required for use.[8]

Subunit Method

The subunit methods for treatment of severe rhinophyma uses 6 nasal flaps to provide exposure for removal of rhinophymatous tissue, correction of nasal support, and trimming of excess “tissue-expanded” skin. The incisions are placed at subunit junctions between the sidewalls and dorsum, dorsum and tip, and alae and sidewalls. The distal nose is then degloved by raising the 6 flaps (2 alar, 2 sidewalls, dorsum, and tip), and rhinophymatous tissue is debulked down to perichondrium.[29] Hassanein et al conducted a case series of 5 male patients receiving subunit surgery for treatment of rhinophyma.[29] The quality of nasal subunits, airway passage, and surgically correctable causes of airway obstruction were evaluated preoperatively for all patients. Depending on the patient’s airway function, tip-defining sutures and cartilage grafts were used for structural support. Three patients required such support due to external valve collapse. If the subunit skin was rendered unusable, the entire subunit could be replaced with full-thickness skin grafts, which was required for 1 patient, as there was severe cobblestoning of his rhinophymatous skin.[29] Similarly, a Hassanein et al review article explored the outcomes for 8 patients who underwent the subunit reconstruction between 2013 and 2016. They demonstrated similar results with 4 patients requiring cartilage grafts and all 8 patients receiving tip-supporting sutures to improve external support. However, neither study provided objective measures to compare preoperative and postoperative nasal obstruction and functional status.[30]

One advantage of the subunit methods is that scars are located at the subunit borders and resemble normal shadows of the nasal surface. Contraction of the skin at healing margins accentuates the native contour of the nose.[29,30] The subunit method also avoids secondary intention healing, thus minimizing hemostatic complications and wound care burden that may come along with scalpel excision[8,30]; however, the wound healing environment is not ideal because of bacterial load and diseased skin associated with rhinophyma.[30] These factors may contribute to scar formation, necessitating further revisional procedures. Six of the 8 patients in the Hassanein et al review underwent correction primarily to modify scars between the dorsum and tip subunits,[30] and 3 of the 5 patients in the Hassanein et al case series had minor scar revisions.[29]

It has been suggested that the subunit method should be considered if cartilaginous modifications are required due to external valve collapse, secondary healing is contraindicated (i.e., patient requires anticoagulation), or if partial excisional techniques have failed to achieve satisfactory nasal contour.[29]

Cartilage Grafting and Vestibular Stenosis Repair

The external nasal valve seems to be the most prone to deformity and insufficient patency postoperatively. The gross deformity of severe rhinophyma and chronic inflammation may potentially weaken the cartilaginous support structures, leading to distortion and obliteration of the aesthetic subunits of the nose.[2] Additionally, the fragility of the cartilaginous framework and damage to cartilage during the removal of the diseased tissue may contribute to poor nasal airway function. No objective assessments, including rhinomanometry, have currently been documented for these patients. The nasal obstruction symptom evaluation (NOSE) score is a validated screening tool for determining the severity of a person’s nasal obstruction, and has been validated in many patients with limited nasal patency due to acquired nasal deformity.[41,42] NOSE scores have been shown to be reliably reduced by roughly 50 points with the use of functional septorhinoplasty. A large systematic review defined normative and symptomatic ranges of NOSE scores as 65 + 22 and 15 + 17, respectively, with an average postoperative change to be greater than 40 points.[43] Future research should focus to more objectively quantify the extent of nasal obstruction preoperatively, which could inform surgical decision-making regarding grafting in the setting of severe rhinophyma.

Despite the risk of insufficient nasal patency in severe rhinophyma, there is minimal research on the use of cartilage grafting as a component of surgical treatment. While Hassanein et al addresses the use of cartilage grafts for external valve support with the subunit method, there is limited evidence suggesting the utility of grafting in combination with other surgical modalities examined in this review. The subunit method addresses excision of the rhinophyma and nasal reconstruction in the same procedure; however, there is minimal evidence comparing cartilage grafting during initial surgery to a staged surgery in which debulking and contouring are included in the first surgery, followed by reconstruction in the second surgery. A possible benefit of reconstruction during the initial surgery is the opportunity to harvest septal cartilage for use as grafts from the same surgical site and to avoid a subsequent exposure to general anesthesia for a staged procedure. Cadaveric grafts could also be used, but there is little evidence on autologous versus cadaver grafting in reconstruction for rhinophyma. Therefore, future research should examine the broad utility of grafting for symptomatic relief of nasal obstruction in the setting of severe rhinophyma.