The Impact of Payment Reform on Pediatric Craniofacial Fracture Care in Maryland

Abstract

:Introduction

Methods

Data Sources

Study Design: Maryland Versus New Jersey

Investigations

Statistical Analyses

Results

Pediatric Craniofacial Fracture Prevention

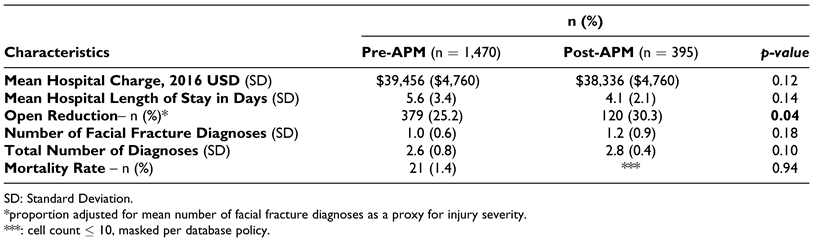

Pediatric Craniofacial Fracture Treatment

Discussion

Maryland as a Test Case for National Trends

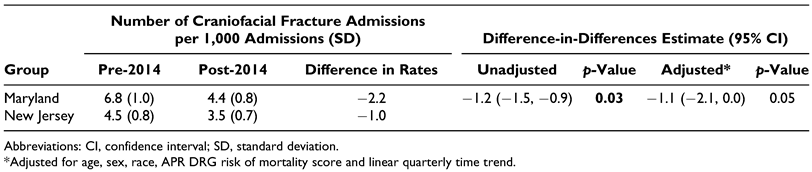

Maryland’s All Payer Model Reduced Admissions for Pediatric Craniofacial Fractures

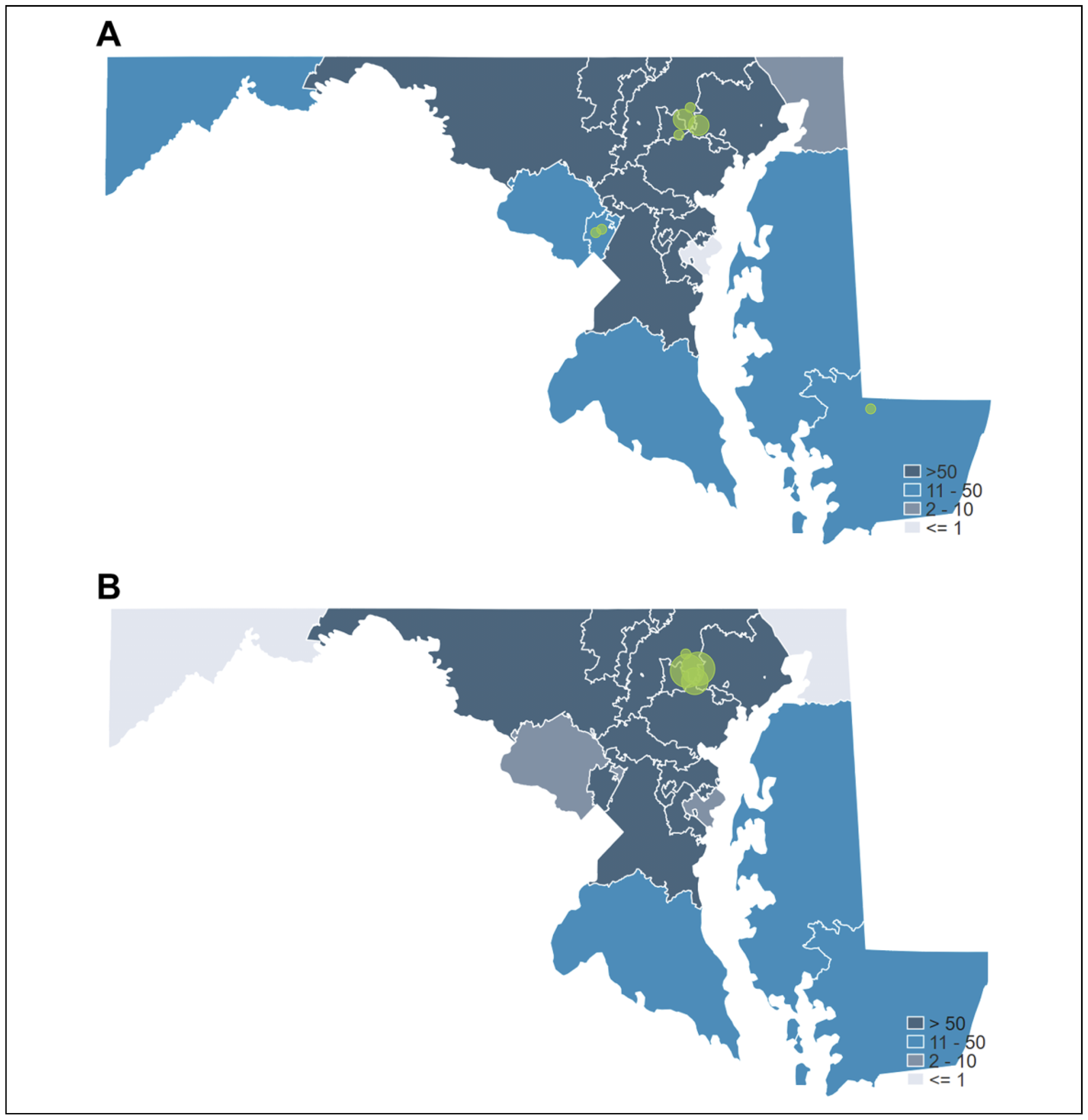

Access to Pediatric Craniofacial Fracture Care

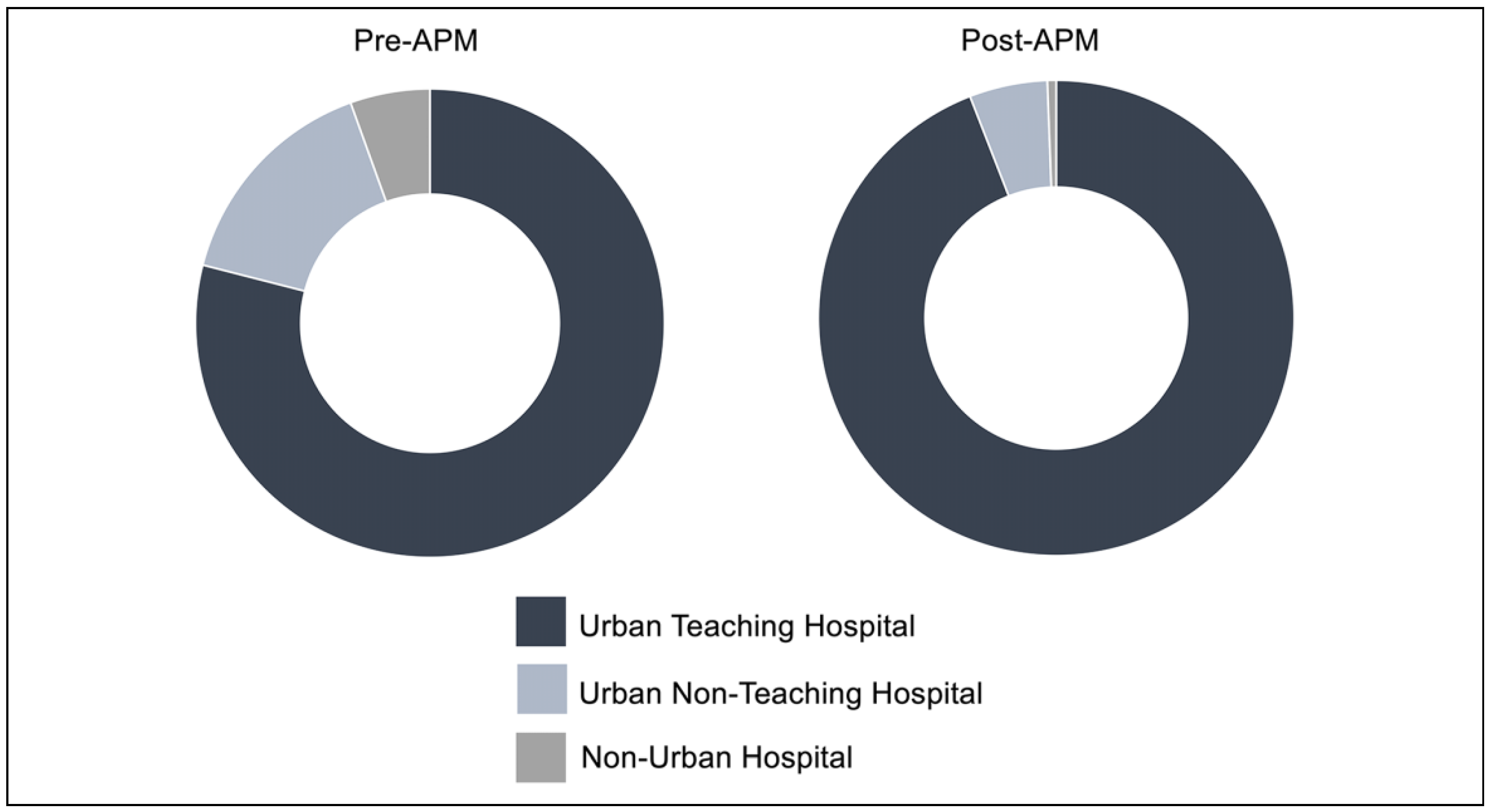

Global Budget Revenues Consolidated Care to Urban Academic Centers

Other Limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wheeler, K.K.; Shi, J.; Xiang, H.; Thakkar, R.K.; Groner, J.I. US pediatric trauma patient unplanned 30-day readmissions. J Pediatr Surg. 2018, 53, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massenburg, B.B.; Sanati-Mehrizy, P.; Taub, P.J. Surgical treatment of pediatric craniofacial fractures: a national perspective. J Craniofac Surg. 2015, 26, 2375–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imahara, S.D.; Hopper, R.A.; Wang, J.; Rivara, F.P.; Klein, M.B. Patterns and outcomes of pediatric facial fractures in the United States: a survey of the National Trauma Data Bank. J Am Coll Surg. 2008, 207, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Rajkumar, R.; Colmers, J.M.; Kinzer, D.; Conway, P.H.; Sharfstein, J.M. Maryland’s global hospital budgets—preliminary results from an all-payer model. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373, 1899–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfstein, J.M.; Gerovich, S.; Chin, D. Global budgets for safetynet hospitals. JAMA 2017, 318, 1759–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.; Herring, B. The all-payer rate setting model for pricing medical services and drugs. AMA J Ethics 2015, 17, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jencks, S.F.; Schuster, A.; Dougherty, G.B.; Gerovich, S.; Brock, J.E.; Kind, A.J.H. Safety-net hospitals, neighborhood disadvantage, and readmissions under Maryland’s all-payer program: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2019, 171, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemel, S.; Riley, T. Addressing and Reducing Health Care Costs in States: Global Budgeting Initiatives in Maryland, Massachusetts, and Vermont; National Academy for State Health Policy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau, Selected Social Characteristics, 2012–2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates; US Census Bureau, 2016.

- Dimick, J.B.; Ryan, A.M. Methods for evaluating changes in health care policy: the difference-in-differences approach. JAMA 2014, 312, 2401–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.R.; Zemplenyi, K.S. Issues in pediatric craniofacial trauma. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017, 25, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqusi, S.; Morris, D.E.; Patel, P.K.; Dolezal, R.F.; Cohen, M.N. Complications of pediatric facial fractures. J Craniofac Surg 2012, 23, 1023–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, R.M.; Dickinson, B.P.; Wasson, K.L.; Roostaeian, J.; Bradley, J.P. Pediatric facial fractures: current national incidence, distribution, and health care resource use. J Craniofac Surg. 2008, 19, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission, Monitoring of Maryland’s New All-Payer Model Biannual Report; The Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission, 2018; 1.

- Beil, H.; Haber, S.G.; Giuriceo, K.; et al. Maryland’s global hospital budgets: impacts on Medicare cost and utilization for the first 3 years. Med Care 2019, 57, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, E.T.; McWilliams, J.M.; Hatfield, L.A.; et al. Changes in health care use associated with the introduction of hospital global budgets in Maryland. JAMA Intern Med. 2018, 178, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, S.; Beil, H.; Adamache, W.; et al. Evaluation of the Maryland All-Payer Model: Second Annual Report; RTI International, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, T. Global Budgets, Payment Reform and Single Payer: Understanding Vemont’s Health Reform; University of Southern Maine, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, P.; Kaufman, Y.; Hollier, L.H., Jr. Managing the pediatric facial fracture. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2009, 2, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antos, J.; Sabatini, N.J.; Kinzer, D.; Haft, H. Maryland’s all-payer model—achievements, challenges, and next steps. Health Affairs Blog, January 31, 2017.

- Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission. Maryland all-payer model agreement. 2014. Updated December 2020. Accessed July 12, 2020. Available online: http://www.hscrc.state.md.us/documents/md-maphs/stkh/MD-All-Payer-Model-Agreement-%28executed29.

- Luckner, M. Community Health Resources Commission Issues Grants to Expand Access to Health Care and Promote Health Services for Vulnerable Residents; Maryland Department of Health, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sapra, K.J.; Wunderlich, K.; Haft, H. Maryland total cost of care model: transforming health and health care. JAMA 2019, 321, 939–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocker, A.B.; Zeymo, A.; Chan, K.; et al. The Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion and utilization of discretionary vs. non-discretionary inpatient surgery. Surgery 2018, 164, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Vargas-Bustamante, A.; Mortensen, K.; Ortega, A.N. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care access and utilization under the Affordable Care Act. Med Care 2016, 54, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, J.; Armon, C.; Griggs, A.; Poole, S.; Berman, S. Increased rates of morbidity, mortality, and charges for hospitalized children with public or no health insurance as compared with children with private insurance in Colorado and the United States. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R. Setting hospital rates to control costs and boost quality: the Maryland experience. Health Aff. 2009, 28, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission. (2015). Completed agreements under the all-payer model: Global budget revenue overview presentation. Updated December 2020. Accessed July 12, 2020. Available online: https://hscrc.maryland.gov/Pages/gbr-tpr.aspx.

- Berenson, R.A. Maryland’s New All-Payer Hospital Demonstration; Urban Institute, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquali, S.K.; Li, J.S.; Burstein, D.S.; et al. Association of center volume with mortality and complications in pediatric heart surgery. Pediatrics. 2012, 129, e370–e376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, J.; Phillips, J. Pediatric facial fractures and potential long-term growth disturbances. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2011, 4, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|

|

© 2021 by the author. The Author(s) 2021.

Share and Cite

Yesantharao, P.S.; Jenny, H.E.; Lopez, J.; Chen, J.; Lopez, C.D.; Aliu, O.; Redett, R.J.; Yang, R.; Steinberg, J.P. The Impact of Payment Reform on Pediatric Craniofacial Fracture Care in Maryland. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2021, 14, 308-316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520983634

Yesantharao PS, Jenny HE, Lopez J, Chen J, Lopez CD, Aliu O, Redett RJ, Yang R, Steinberg JP. The Impact of Payment Reform on Pediatric Craniofacial Fracture Care in Maryland. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2021; 14(4):308-316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520983634

Chicago/Turabian StyleYesantharao, Pooja S., Hillary E. Jenny, Joseph Lopez, Jonlin Chen, Christopher D. Lopez, Oluseyi Aliu, Richard J. Redett, Robin Yang, and Jordan P. Steinberg. 2021. "The Impact of Payment Reform on Pediatric Craniofacial Fracture Care in Maryland" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 14, no. 4: 308-316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520983634

APA StyleYesantharao, P. S., Jenny, H. E., Lopez, J., Chen, J., Lopez, C. D., Aliu, O., Redett, R. J., Yang, R., & Steinberg, J. P. (2021). The Impact of Payment Reform on Pediatric Craniofacial Fracture Care in Maryland. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 14(4), 308-316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520983634