A literature review was completed, identifying resources and current data regarding the safe resumption of clinical activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Primary resources of information included the Center for Disease Control Website (CDC), US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and World Health Organization (WHO). Additionally, protocols developed by other countries that successfully contained spread of the virus, including Germany and New Zealand, were reviewed and will be addressed.

Planning Prior to Departure

Collaboration and coordination with the hosting institution. As with any mission trip, close collaboration with leaders from the hosting institution are imperative, not only for success of the overall mission, but now for COVID-19 related health issues and depletion of local resources.[

17] Team leaders should discuss the potential risks of travel and the availability of host supplies and personnel. The personnel, facilities, and supplies that were once available to the organization may now be allocated to caring for COVID-related illnesses. If a deficit exists, team leaders should determine if they will be able to compensate for these shortages.

The incidence and prevalence of COVID-19 at the destination site should also be carefully monitored. While the incidence of COVID-19 may be declining in many countries, some countries have restricted travel into their borders. If this information is unavailable due to lack of testing, local collaborators should be consulted. Organizations should avoid traveling to known COVID-19 hotspots; this includes locations where the incidence of COVID-19 infections is escalating or where lockdowns are still in effect. Teams should wait at least 14 days after mandatory lockdowns have been lifted to travel into the country. Careful consideration of the risks and benefits of travel should be conducted, particularly if there is reason to believe that the true number of cases are underreported or if there is lack of testing available in the country.

Organization and host leaders should develop protocols and clinical workflows according to the facilities, personnel, and supplies available.[

17] Planning disputes should be resolved prior to departure; it is also important that the traveling organization remembers they are guests in the host’s institution. Management of COVID+ patients, team training, and clinical workflow should be included in the protocol(s). All organization and local team members participating in patient care should be familiarized with these protocols.

COVID-19 testing and other equipment considerations. COVID-19 testing for personnel and patients is imperative for the safe execution of mission work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lack of available testing may unnecessarily elevate health and safety risks and is an indication for postponing the trip. Availability and accuracy of testing at the host institutions must be assessed during the planning process. As previously discussed, these resources might not be available at the host institution or may be reserved for other purposes; organizations should determine if funding permits providing tests. If local resources are deficient or reserved, and the team does not have the available funding to purchases tests for all involved personnel and patients, then missions to these should be postponed until COVID-19 testing or vaccinations become available.

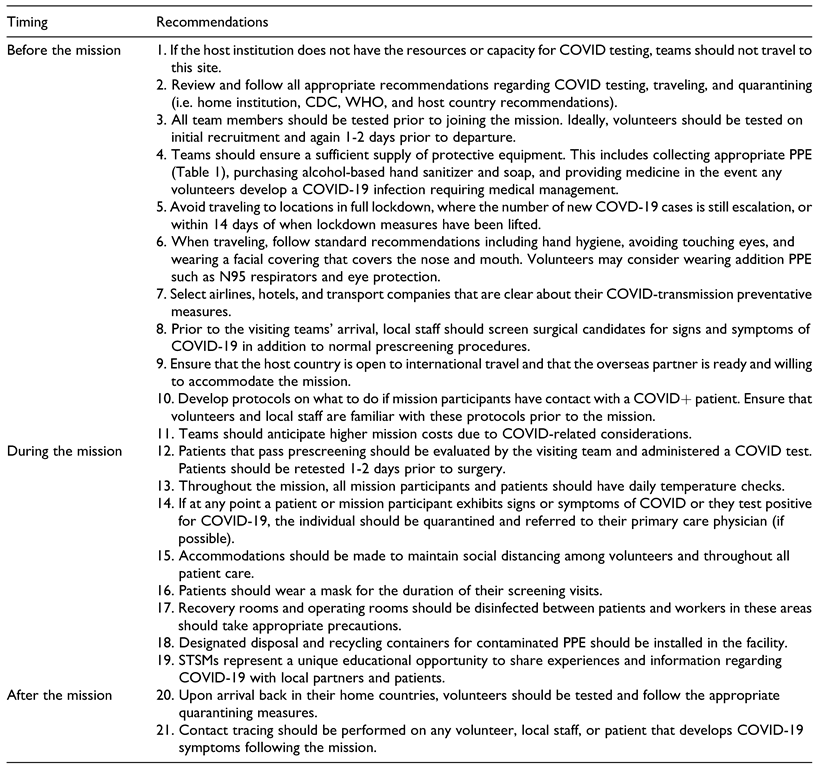

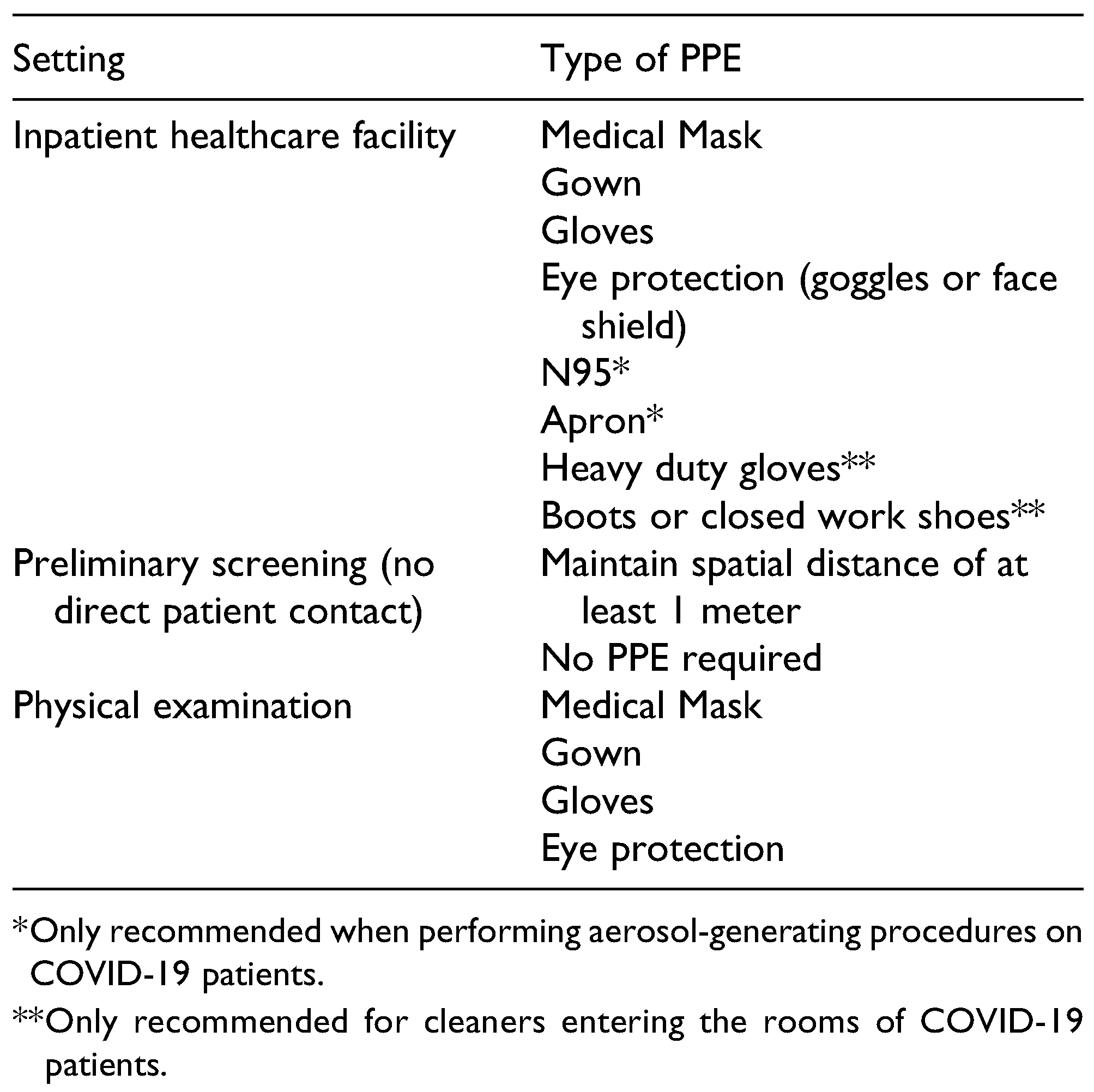

Table 1.

Recommended PPE.[

18,

19].

Table 1.

Recommended PPE.[

18,

19].

In addition to COVID-19 tests, additional personal protective equipment (PPE) will need to be procured to safely execute clinical operations. The safety of the patients and the team’s personnel depends on its availability and distribution. A comprehensive list of indicated PPE for dentistry and craniomaxillofacial surgery is depicted in

Table 1. All team members (organizational and host) should be trained to properly don and doff, and dispose of the equipment. Emphasis should be made to preserve reusable supplies and to prevent cross-contamination between patients. PPE should also be provided to non-healthcare providing team members, including those involved with transportation, translation serves, etc. and patient family members. Team leaders should encourage all team members to carry alcohol-based hand sanitizers and wash their hands frequently. The amount of anticipated PPE should be calculated prior to purchase; hoarding of PPE should be discouraged as depleting sources of supply negatively affects other services.[

20] The greater PPE requirement will also use more of the organization’s funds; lack of funding to purchase PPE is also an indication for postponing the mission.

Supplies should be obtained from the host country or purchased prior to departure to ensure their availability. If shortages prevent the purchase of supplies in the organization’s home country, confirmation of purchase from the local team leaders should be sought. If supplies are not available in either country, this may be in indication that they are needed for the management of COVID-19 related illnesses and should prompt the teams to consider deferring the trip until supplies are available. If a surplus of acquired supplies exists, these should be returned as to avoid the depletion of supplies.[

21]

At the time of the writing, the CDC and FDA have not approved the use of any single medication for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.[

22] Previously investigated medications, including hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine, have been retracted for the treatment of COVID-19 as the risk of adverse side effects outweighs the unknown treatment benefits. Other proposed medications, including dexamethasone, continue to be investigated for efficacy. Further research is needed before the FDA approves a medication for the treatment of COVID-19; Use of any medication for symptomatic treatment is considered to be “off-label.”[

20] Laws and regulations pertaining to the country of origin should be reviewed and followed when considering the use an “off-label” medication. For this reason, the World Health Organization (WHO) does not recommend purchasing and stockpiling medications for the sole purpose of preventing and treating COVID-19 infections. Shortages of stockpiled drugs may occur, preventing treatment of other indicated diseases.[

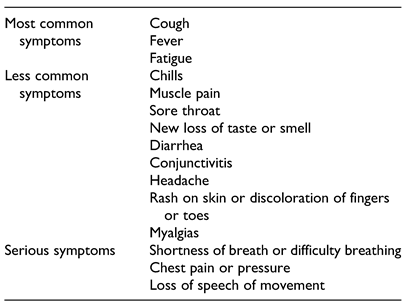

21] Additionally, mildly symptomatic cases of COVID-19 usually self-resolve. A 14-day quarantine is recommended with minimal to no medical management is typically all that is necessary. If a COVID-positive individual develops shortness of breath, daytime somnolence, new onset chest pain, or cyanosis of the lips, the individual should then seek medical management (higher level of care); a complete list of COVID-19 related symptoms may be found in

Table 2. This case would be more severe and is more commonly seen in high-risk populations. For this reason, prevention should be the primary strategy through the implementation of social distancing protocols, use of PPE, and selecting team members that are in good general health (low-risk). If severe illness does occur, prior preparations should be made for evacuation back to the United States. The FDA, CDC, and WHO websites should be regularly reviewed for the most up-to-date information.[

20,

21,

22]

Table 2.

Possible Signs and Symptoms of COVID-19.[

23,

24].

Table 2.

Possible Signs and Symptoms of COVID-19.[

23,

24].

Preparation of team members: COVID-19 precautions for international travel. The number of team members will depend on the number of anticipated patients, the availability of supplies, and capacity of the facilities. These should be predetermined during initial conversations with the local team leaders. If the number of members needed is restricted, preference should be given to those that can complete multiple duties, such as individuals that serve as assistants and translators. Medical screening exams should also be considered as high-risk individuals may be assuming an unnecessarily high risk if traveling. Once the team is finalized, communication and training are critical for mission success.

As previously stated, all team members should be trained and oriented to the proper of use of PPE, and to clinical workflows. Travel guidelines should be reviewed and emphasized. Frequent and regular communication through the form of video conferences and email can be used as a method to increase compliance. All members should be encouraged to speak with their families and employers prior to departure, as a mandatory 14-day quarantine may be enforced upon their return.

Lodging and travel accommodations should be assessed for sanitation and social distancing measures prior to reservation. Leaders should inquire as to what measures will be taken to ensure social distancing, including the maximum capacity the hotel or host is willing to take in, and symptom screenings. When possible, private transportation is recommended over public transportation as there is more control of social distancing and less exposure to non-members. If teams are accustomed to using public transportation, private transportation will add an additional cost; if private transportation is not available, the assessment of local infection rates, availability of testing, and access to masks become even more important.

Regardless of the travel destination or team composition, all volunteers should be encouraged to comply with hand-hygiene protocols, washing their hands thoroughly and frequently. Encourage all individuals to avoid touching their faces, and to wear masks covering the nose and mouth at all times. Current CDC data indicates that the spread of the COVID-19 virus happens most often during close gatherings of individuals that are not wearing PPE; transmission of the virus on planes has been found to be minimal due to air circulation and filtration systems when masks are worn.[

25] Given this information, social distancing during travel should be enforced as much as possible. Airlines with transparent COVID-19 sanitation and social distancing policies should be chosen when available. This information is typically available on the airline’s website.

Closer to the departure date, all team members should be screened for COVID-19 symptoms. If a team member contracts COVID-19 prior to departure, it may be prudent to request that individuals on standby be available to take their place. As with any mission, setbacks will occur and should be anticipated and accounted for as much as possible. Regardless of symptoms, all team members should be tested for COVID-19; this is for the purpose of detecting asymptomatic carriers of the virus prior to departure. The organization may make these tests available if funding permits; otherwise all volunteers should be required to show proof of a negative test. If possible, team leaders should consider testing members twice, as there is a high false negative rate associated with the RT-PCR test.[

26] Testing should be completed with sufficient time to receive results back as close to the departure day as possible. Antibody testing should also be considered, as antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 confer immunity; preference for team membership might be given to individuals with antibodies. The same testing procedures should also be required of local personnel. If testing is not available for local personnel or patients, travel to this location should be deferred until testing or vaccinations become available.

Prescreening patients. Patient prescreening should be the first step in the process of identifying surgical candidates; survey administration and temperature checks should be conducted on every patient and his or her family without exception. If patients present with family, the number of family members with access to the facility should be minimized; it is prudent to consult the local hosts on this matter as it may present a cultural conflict. Patients displaying signs or symptoms of COVID-19 infection, or that have had close contact with a COVID-positive patient in the last 2 weeks should be asked to self-isolate and/or be referred to their primary care doctor.[

27,

28] If the patient passes the initial screening exam, they should be tested for COVID-19 prior to surgical treatment. For the purposes of the mission, patients that test positive for COVID-19 are not eligible for elective surgical procedures.

COVID-related financial considerations. The need for additional preparedness during the COVID-19 pandemic also implies additional expenses. These additional expenses should be considered and accounted for during the initial planning stages to ensure the organization is sufficiently funded prior to purchasing needed supplies. Budget expansion may be necessary for the following areas:

- (a)

Additional supplies, and associated shipping and storage costs—The need for PPE and testing kits increases the number of items needed for purchase and transport. This additional need is intuitively more expensive. Leaders should also consider how this additional supply will be transported. If it is being shipped or carried in luggage, the additional space occupied or weight may also incur a greater fee. Storage of these supplies may also be more expensive for similar reasons.

- (b)

Changing airline prices—Airline companies have suffered considerable losses as result of travel restrictions. To recuperate these losses, the companies may be forced to charge more per ticket, particularly if they are not filling each flight to capacity.[

25]

- (c)

Accommodations during travel and lodging— Before the pandemic, many team members would share rooms or traveling expenses for economical purposes. To comply with social distancing, team members may not be permitted to do so, requiring that more rooms be reserved to ensure distancing. Additionally, private transportation may be necessary to reduce exposure and risk of infection.

- (d)

Traveler’s insurance—As with any mission, it is always recommended that all traveling parties purchase traveler’s insurance for medical, and now for transportation. In the wake of COVID-19, medical insurance rates may be more expensive due to the assumed risk of traveling during a pandemic. Airline insurance should also be considered as last-minute cancellations are possible due to outbreaks or changes in quarantine requirements.

Another consideration includes the financial sustainability of the organization. As we will discuss, the number of necessary procedure modifications necessary to reduce the spread of infection may result in a significantly reduced caseload. The anticipated number of patients should be estimated with the help of local officials; factors including the number of previously treated patients, the number of COVID-positive cases, and incidence trend should be used to calculate this value. The decision to proceed with this mission should be based on the marginal cost of the mission (i.e. the cost to successfully complete the mission) and the marginal social benefit. If the marginal cost exceeds the social benefit, proceeding with the mission may prove to be unnecessarily costly and may jeopardize the financial health and longevity of the organization. While it is difficult to monetarily quantify the value of treating an individual patient and the benefits they receive from the procedure(s) (it is undeniable that it is exceedingly rewarding), treating a limited number of patients on 1 mission may prevent the treatment of many others if the financial health of the organization is not sustained. Team leadership must careful review their budgets and plans while making such important decisions.

On the Ground

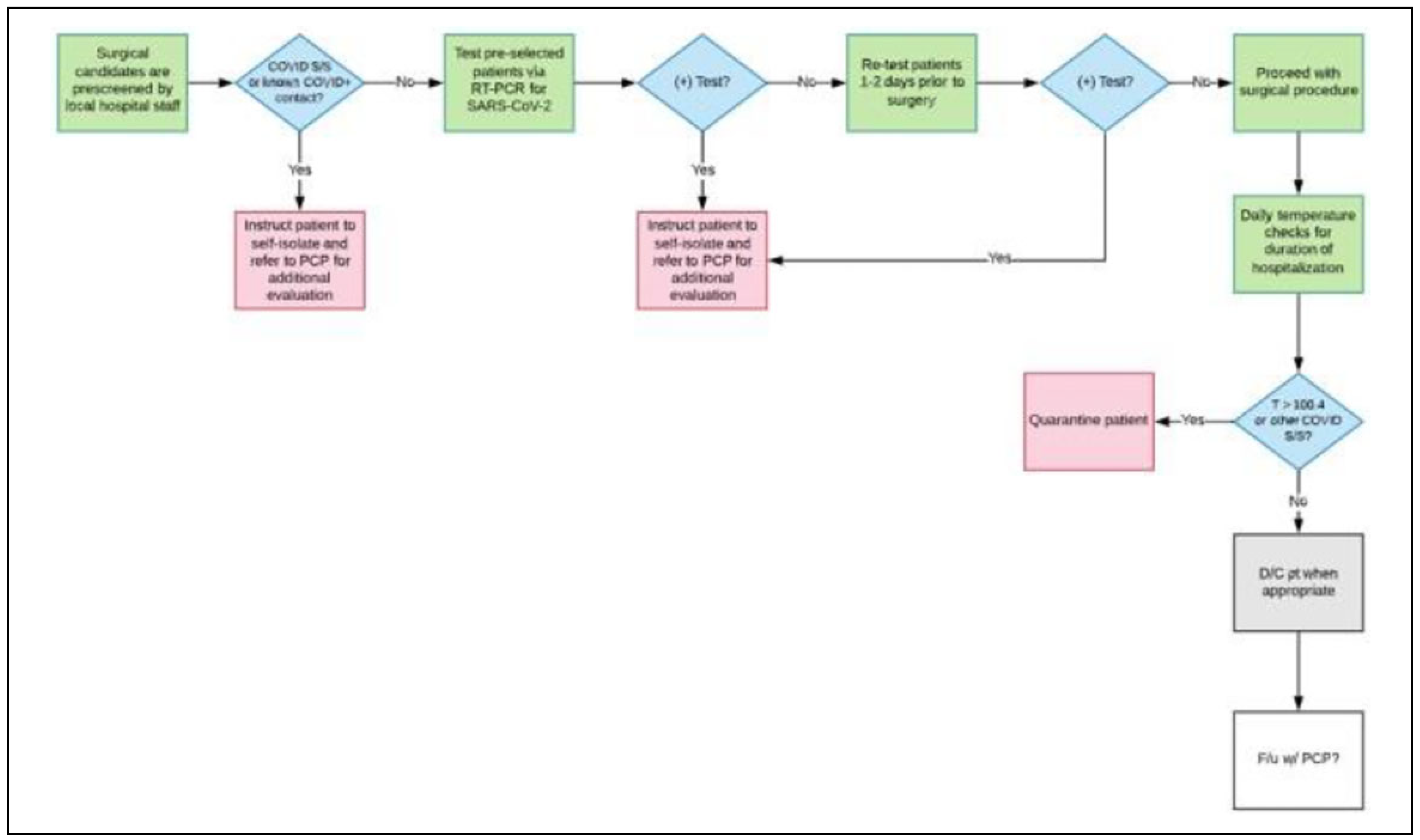

As previously mentioned, until a vaccine is developed and distributed, only patients that test negative for COVID-19 should be candidates for elective surgical procedures. For this reason, all team members should strictly adhere to screening and testing protocols; this is for the safety of the patients, their families, and the team personnel. Any deviations from protocol should be immediately addressed as the success of the mission depends on this. An example of workflow for screening and testing patients can be found in

Figure 1.

COVID-19 screening and testing. To facilitate the screening process, patients should be screened by local personnel prior to the arrival of the surgical team. If this is not possible, the surgical team will need to complete this step before continuing any other steps. Asymptomatic patients should then be tested for COVID-19; those who test positive should be asked to self-quarantine for 14 days and/or referred to their primary care physician as necessary.[

27,

28] If enough tests are available, patients should undergo a second test 1 to 2 days prior to the surgical procedure (as needed) due to the high false negative rate.[

26] Similar screening tests should be administered to all volunteers: this includes daily temperature checks and additional tests if volunteers are exposed to a COVID-19 positive patient. If any team personnel tests positive for COVID-19 at any time during the mission, they should be quarantined and removed from all mission operations until the infection has resolved.[

27,

28]

Social distancing procedures. In order to reduce the risk of exposure, social distancing procedures should be included in the facility medication plans and workflow protocols. These procedures should be communicated to all individuals participating in patient care. During the mission, team members should adhere to social distancing procedures in and outside of the patient care setting, including team meetings and meal times. When possible, smaller sub-teams may be created and rotated to reduce cross-exposures.[

29] Individual talents should be assessed and teams should be divided equally so that patient care quality is not compromised. The number of team members rounding to see admitted patients should also be limited. Other team members should be updated on their status without unnecessarily increasing exposure to the patient. In general, it is best to limit the number of clinical activities to the minimal number of individuals necessary to complete the objective. Patients should also be instructed to comply with these new regulations. If locals permit family members to be present during patient care, social distancing and mask wearing should be encouraged. PPE should be provided to all individuals that have been cleared to come in contact with the patient. The number of individuals permitted to visit patients should be limited as much as possible. Of course, cultural considerations should be considered when requesting these modifications and should be discussed with local leadership.

Throughout the facility, signs and labels, including floor markers and other visual reminders, may be used to enforce social distancing. Chairs should be separated in waiting rooms to decrease patient-to-patient contact. Arrows and signs may be used to designate entries and exits, and to prevent non-personnel from entering restricted areas. Transparent dividers may also be used to protect patient and volunteers during registration or other activities that do not require direct patient contact.

Procedure modifications. Upon arrival, all patients and family members should receive a screening survey and temperature screening before permitted to enter the facility. Masks should be worn by all individuals at all times. Volunteers should be appointed to completed these screenings and temperature checks; all team members should be asked to reinforce mask wearing by patients and their families.

Elective treatment should be reserved for test confirmed COVID-negative patients. When treating COVID-positive patients requiring emergency surgery, necessary precautions should be adhered to and observed. Due to the limited number of ventilators and high transmission rate associated with oropharyngeal secretions, intubations should be avoided when possible and all personnel treating the patient should wear the indicated PPE. Spinal anesthesia may be used in lieu of general anesthesia in eligible patients. For these reasons, pediatric patients may be more challenging to treat as patient compliance under local anesthesia may not be achievable, requiring the use of general anesthesia and intubation. Additionally, for oral and maxillofacial surgeons treating cleft lip and/or palate patients, the increased exposure to oropharyngeal secretions may pose a particularly higher risk to surgical teams. Cleft lip and palate surgeries (including palatoplasties and other sinus surgeries) should consider postponing all missions until a vaccination is developed to avoid assuming unnecessary risks.

The surgical team should discuss what procedure modifications on a facial surgical mission to reduce exposure to COVID-19. Case selection is of critical importance. Long or unnecessarily complicated procedures should be limited when possible. Shorter procedures with minimal complication risk that can be completed under local anesthesia should be prioritized.

These modifications will protect the surgical team, but these medications may come at a price—specifically it may reduce the surgical volume during said mission. If leadership anticipates that the surgical volume is insufficient to carry out a surgical mission, this may be remedied by potentially reducing the team size, or postpone mission until vaccine is available. These are decisions an organizations leadership must not take lightly. While team and patient safety is paramount, postponing missions can have tangible and non-tangible repercussions. Most importantly, the sponsoring organization may lose momentum gained by running consistent, annual or biannual trips. This could include losing medical/surgical volunteers as well losing financial sponsorships. Further the host hospitals of NGOs (no with increased case load and need) may look to other avenues for meeting this need.

Facility and equipment modifications. When available, procedures generate aerosols (i.e. require the use of a piezo or handpiece) should be completed in an enclosed room with negative pressure ventilation. These rooms, which are often limited, should not be used for procedures with minimal to no risk of aerosol generation. Particularly in the oral cavity, the ability to suction oropharyngeal secretions is crucial.[

30] If these rooms or suction are not available, as in many rural clinical settings, the team should discuss if this possess and unnecessarily high risk of COVID-19 exposure.

All chairs and rooms should be adequately disinfected between patients. The individuals tasked with sanitation and sterilization should be provided PPE, including nursing and custodial staff. All disposal bins should be clearly labeled; biohazard should be disposed of per local regulations. If equipment is reusable, these items should also be placed in a clearly labeled container and be sterilized promptly.[

30] Hand sanitizer, hand washing stations, and disinfecting wipes should be labeled and be made readily available for all personnel. They should be used regularly between patients.

Educational opportunities. The COVID-19 pandemic changed the landscape of modern education. In order to enforce social distancing measures, healthcare providers and educators increasingly employed the use of videoconference technology to continue patient visits and educational sessions. The advancement and increased use of this technology provides mission leaders a unique opportunity to share their experiences with others around the world. As providers engage in STSMs, videoconference technology allows teams to share their experiences using these modified COVID-19 protocols. This information is invaluable as it provides a framework for how to proceed with STSMs during the current pandemic, future pandemics, and countries with endemic diseases. Additionally, it may also be useful during the mission, as it provides another method to convey information to team members when patient contact is more limited. While social distancing restrictions limit the number of personnel that may contact patients or operate, team leaders can use this technology to continue the educational objectives of the team. It may also be used to reinforce the relationship between team members and local surgeons (residents and attendings, alike). As always, use of this technology should not compromise patient confidentiality; all videos, photos, and patient information should be protected. Appropriate use of technology should be reviewed with all team members as to avoid exploitation of patients and violation of their confidentiality.

Returning home: necessary measures. As previously discussed, all team members should review their local regulations and discuss travel plans with employers and family prior to departure. Individuals required to quarantine per employment/institutional mandate should self-isolate as indicated. Regardless of local regulations or work requirements, all individuals should be tested for COVID-19 if available and conduct daily temperature checks for 14 days.[

28] Team members that test positive for COVID-19 should report positive results to the team’s leadership; contact tracing should be completed and individuals should quarantine as necessary.

Successful international protocols: additional recommendations. While the CDC, FDA, and WHO have made recommendations previously stated, recommendations from other countries that successfully contained the virus, including Germany and New Zealand, should be noted. Leadership from Germany and New Zealand placed great emphasis on rapid, science-based responses to the pandemic. This includes clear, non-conflicting information from all officials.

In Germany, the first case of COVID-19 was reported on January 27. By February 27, with 26 confirmed cases, officials established a crisis management group, implementing mandatory testing for all travelers coming to Germany from high risk areas. Daily situation reports became available through the Robert Koch Institute (RKI). With extensive social distancing measures (no more than public gatherings of 2 people), closure of schools and businesses, extensive communication of scientific information, and readily available COVID-19 testing, Germany was able to significantly reduce the spread of the virus. While prevention of COVID-19 was not achieved, early diagnostics, the development of situational mathematical models, and interventions were critical to reducing mortality in Germany. German officials emphasize the importance of collecting diagnostic information, rapid application of action plans, and concise delivery of scientific information.[

29,

30]

As in Germany, clear, concise communication, and rapid action played a critical role in the elimination of COVID-19 from New Zealand. After the WHO announced the outbreak to be a public emergency on January 30, 2020, government officials from New Zealand immediately implemented disease prevention measures. This included strict closure of borders and adherence to social distancing protocols. The first case in New Zealand was reported on February 28. After announcement of the first case, the government tightened restrictions, and focused on speedy testing, contact tracing, and rigorous adherence to public health guidance. In addition to extensive testing and isolation measures, scientific communication and strong leadership has been noted to be key in New Zealand’s success; in order to emphasize the importance of adherence to public health guidance, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern communicated key information to the public, emphasizing the importance of a “team of 5 million.” The last case of COVID-19 was identified in early May and by June 8, New Zealand declared the end of the pandemic.[

31,

32]

Four important lessons/recommendations can be deduced from the international models described above: the importance of (1) situational evaluations and diagnostic information, (2) rapid action for prevention and treatment of COVID-19, (3) clear and concise communication, and (4) firm, unifying leadership. Both countries model the importance of evaluating public health data. Germany rapidly implemented measures of collecting public health data and made this information readily available to the public through the RKI. Both countries also extensively communicated scientific information to the public as the pandemic progressed. When preparing a team for a mission, these principles should be applied. Close collaboration with local officials should elicit public health information that should then be used to rapidly implement prevention measures to protect the team and the patients. All information pertaining to the virus and local public health information should be regularly communicated to the team. Additionally, rhetoric should be used to unite the team and emphasize the importance of teamwork and the common goal: health and safety. As previously mentioned, COVID-19 testing, social distancing measures, and contact tracing are imperative to preventing spread of COVID-19.