Interfacility Transfers for Isolated Craniomaxillofacial Trauma: Perspectives of the Facial Trauma Surgeon

Abstract

:Introduction

Material and Methods

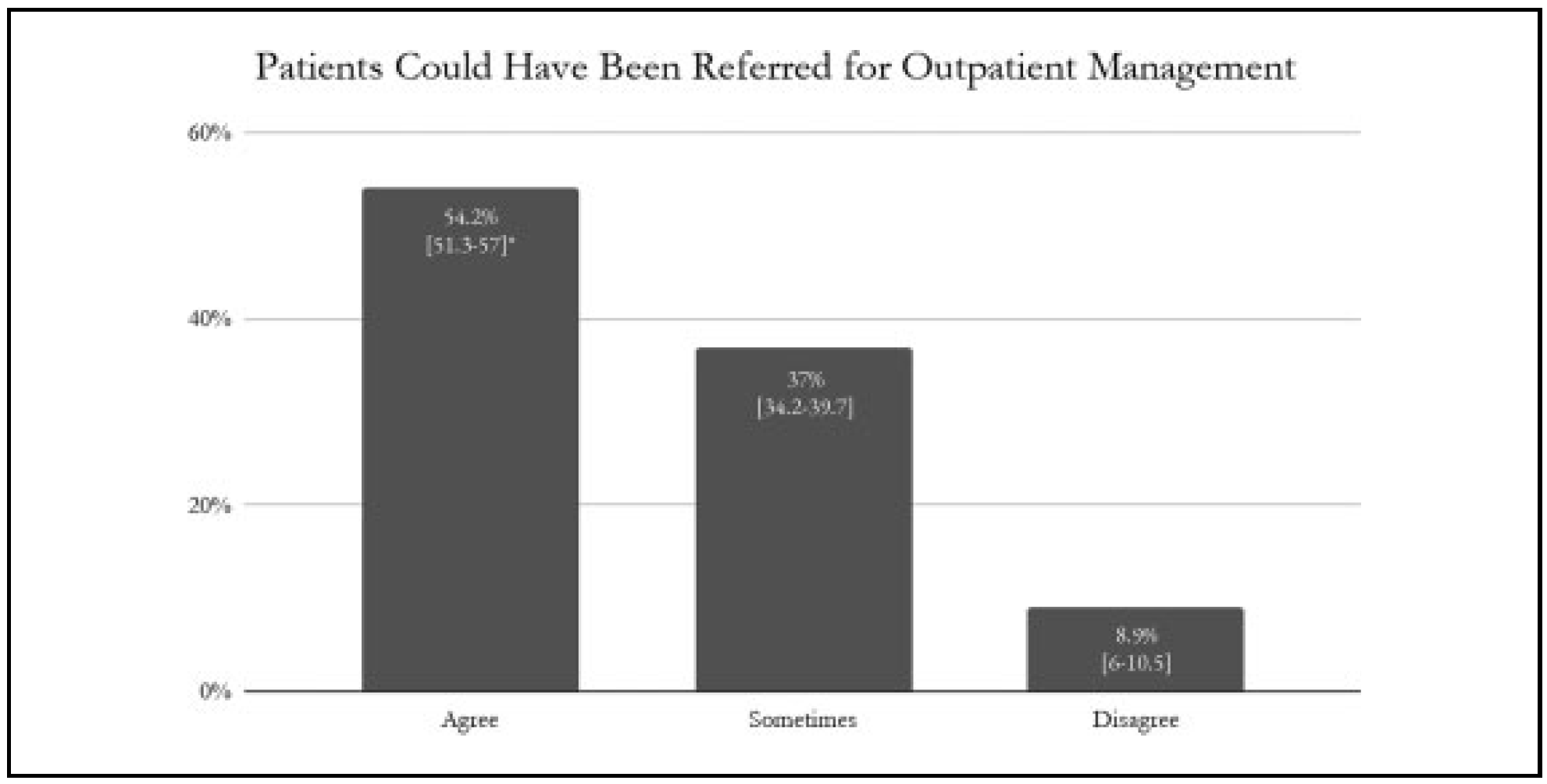

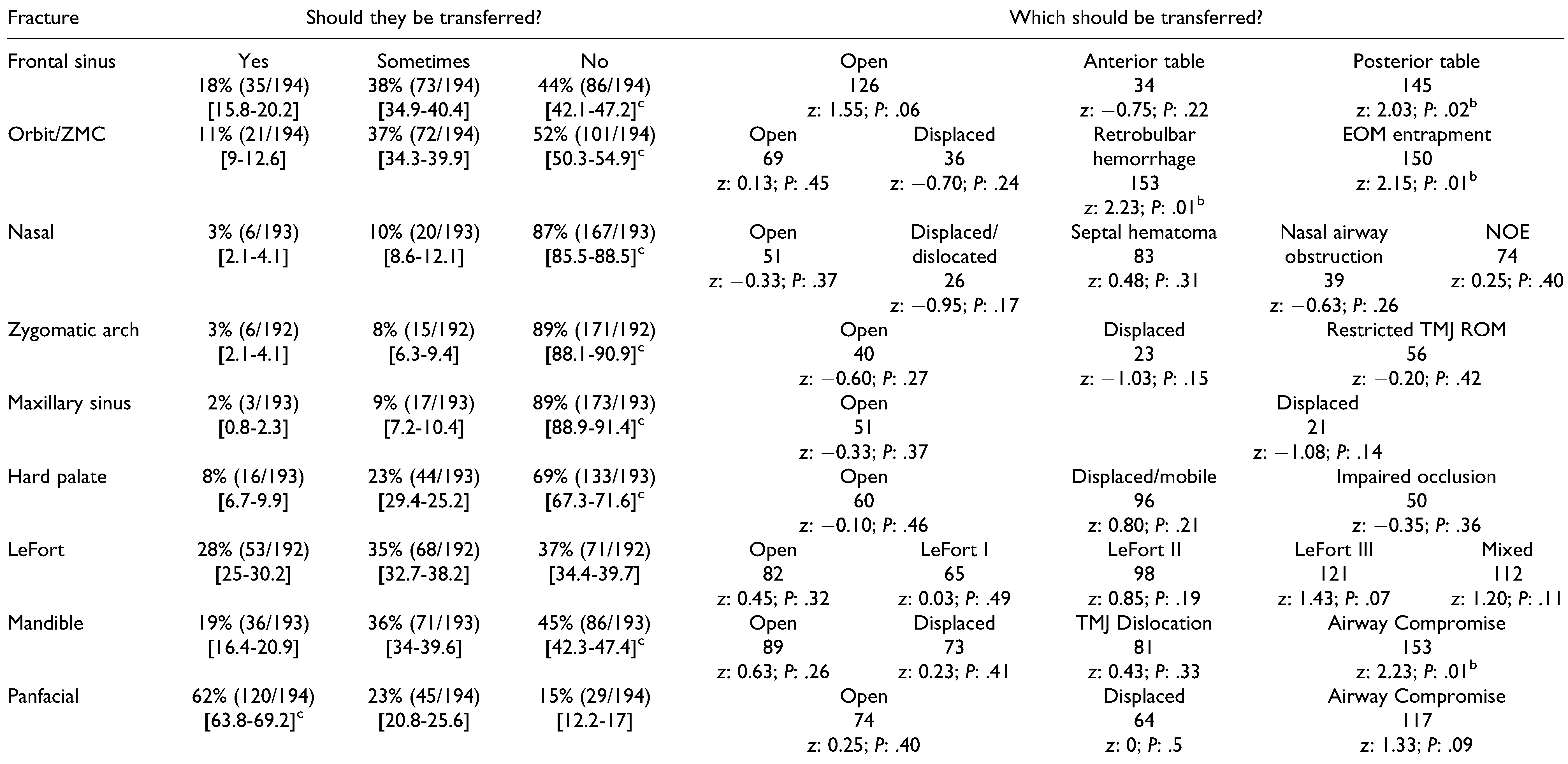

Results

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MacKenzie, E.J.; Rivara, F.P.; Jurkovich, G.J.; et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006, 354, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampalis, J.S.; Denis, R.; Fre´chette, P.; Brown, R.; Fleiszer, D.; Mulder, D. Direct transport to tertiary trauma centers versus transfer from lower level facilities: impact on mortality and morbidity among patients with major trauma. J Trauma. 1997, 43, 288-295; discussion 295-296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampalis, J.S.; Denis, R.; Lavoie, A.; et al. Trauma care regionalization: a process-outcome evaluation. J Trauma. 1999, 46, 565-579; discussion 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasser, S.M.; Hunt, R.C.; Sullivent, E.E.; et al. Guidelines for field triage of injured patients: recommendations of the National Expert Panel on Field Triage. MMWR Recommen Rep. 2009, 58, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cielsa, D.J.; Sava, J.A.; Street, J.H.; Jordan, M.H. Secondary overtriage: a consequence of an immature trauma system. J Am Coll Surg. 1998, 206, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, A.; Hashmi, A.; Pandit, V.; et al. A critical analysis of secondary overtriage to a level I trauma center. J trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014, 77, 969–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utter, G.H.; Maier, R.V.; Rivara, F.P.; et al. Inclusive trauma systems: Do they improve triage or outcomes of the severely injured? J Trauma. 2006, 60, 529-535; discussion 535-537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haas, B.; Gomez, D.; Zagorski, B.; et al. Survival of the fittest: the hidden cost of undertriage of major trauma. J Am Coll Surg. 2010, 211, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient, American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, 2006.

- Mullins, R.J. A historical perspective of trauma system development in the United States. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 1999, 47 (3Suppl), S8–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracht, E.E.; Tepas, J.J., 3rd; Celso, B.G.; Langland-Orban, B.; Flint, L. Survival advantage associated with treatment of injury at designated trauma centers: a bivariate probit model with instrumental variables. Med Care Res Rev. 2007, 64, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathens, A.B.; Jurkovich, G.J.; Rivara, F.P.; Maier, R.V. Effectiveness of state trauma systems in reducing injury-related mortality: a national evaluation. J Trauma. 2000, 48, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A.; Barlow, B.; DiScala, C.; String, D.; Ray, K.; Mottley, L. Efficacy of pediatric trauma care: results of a populationbased study. J Pediatr Surg. 1993, 28, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hulka, F.; Mullins, R.J.; Mann, N.C.; et al. Influence of a statewide trauma system on pediatric hospitalization and outcome. J Trauma. 1997, 42, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pracht, E.E.; Tepas, J.J., 3rd; Langland-Orban, B.; Simpson, L.; Pieper, P.; Flint, L.M. Do pediatric patients with trauma in Florida have reduced mortality rates when treated in designated trauma centers? J Pediatr Surg. 2008, 43, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newgard, C.D.; Staudenmayer, K.; Hsia, R.Y.; et al. The cost of overtriage: more than one-third of low-risk injured patients were taken to major trauma centers. Health Aff (Milwood). 2013, 32, 1591–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.D.; Fowler, R.A.; Nathens, A.B. Impact of interhospital transfer on outcomes for trauma patients: a systematic review. J Trauma. 2011, 71, 1885-1900, discussion 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivara, F.P.; Koepsell, T.D.; Wang, J.; Nathens, A.; Jurkovich, G.A.; Mackenzie, E.J. Outcomes of trauma patients after transfer to a level I trauma center. J Trauma. 2008, 64, 1594–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, M.J.; von Recklinghausean, F.M.; Fulton, G.; Burchard, K.W. Secondary overtriage: the burden of unnecessary interfacility transfers in a rural trauma system. JAMA Surg. 2013, 148, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osen, H.B.; Bass, R.R.; Abdullah, F.; Chang, D.C. Rapid discharge after transfer: risk factors, incidence, and implications for trauma systems. J Trauma 2010, 69, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, T.J.; Crandall, M.; Reed, R.L.; Gamelli, R.L.; Luchette, F.A. Socioeconomic factors, medicolegal issues, and trauma patient transfer trends: Is there a connection? J Trauma. 2006, 61, 1380-1386, discussion 1386-1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koval, K.J.; Tingey, C.W.; Spratt, K.F. Are patients being transferred to level-I trauma centers for reasons other than medical necessity? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006, 88, 2124–2132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spain, D.A.; Bellino, M.; Kopelman, A.; et al. Requests for 692 transfers to an academic level I trauma center: implications of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act. J Trauma. 2007, 62, 63-67; discussion 6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathens, A.B.; Maier, R.V.; Copass, M.K.; Jurkovich, G.J. Payer status: the unspoken triage criterion. J Trauma 2001, 50, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newgard, C.D.; McConnell, K.J.; Hedges, J.R. Variability of trauma transfer practices among non-tertiary care hospital emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2006, 13, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drolet, B.C.; Tandon, V.J.; Ha, A.Y.; et al. Unnecessary emergency transfers for evaluation by a plastic surgeon: a burden to patients and the health care system. Plast Reconstr Surg 2016, 137, 1927–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medford-Davis, L.N.; Holena, D.N.; Karp, D.; Kallan, M.J.; Delgado, M.K. Which transfers can we avoid: multi-state analysis of factors associated with discharge home without procedure after ED to ED transfer for traumatic injury. Am J Em Med. 2018, 36, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontell, M.E.; Colazo, J.M.; Drolet, B.C. Unnecessary interfacility transfers for craniomaxillofacial trauma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020, 145, 975e–983e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.N.; Schaefer, G.P. Evaluation of which isolated facial trauma needs transfer to a tertiary care center. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2018, 227, e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.M. An EMTALA primer: the impact of changes in the emergency medicine landscape on EMTALA compliance and enforcement. Ann Health Law. 2004, 13, 145–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nathens, A.B.; Jurkovich, G.J.; Cummings, P.; Rivara, F.P.; Maier, R.V. The effect of organized systems of trauma care on motor vehicle crash mortality. JAMA. 2000, 283, 1990–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celso, B.; Tepas, J.; Langland-Orban, B.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing outcome of severely injured patients treated in trauma centers following the establishment of trauma systems. J Trauma. 2006, 60, 371-378; discussion 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzoli, G.J.; Madura, K.J.; Cooper, G.F.; et al. Progress in the development of trauma systems in the United States. JAMA. 1995, 273, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niska, R.; Bhuiya, F.; Xu, J. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2007 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010, 26, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, S.L.; Moore, E.E. The integral role of the plastic surgeon at a level I trauma center. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003, 112, 1371-1375, discussion 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, E.J.; Weir, S.; Rivara, F.P.; et al. The value of trauma center care. J Trauma. 2010, 69, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfarb, M.G.; Bazzoli, G.J.; Coffey, R.M. Trauma systems and the costs of trauma care. Health Serv Res. 1996, 31, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Durham, R.; Pracht, E.; Orban, B.; Lottenburg, L.; Tepas, J.; Flint, L. Evaluation of a mature trauma system. Ann Surg. 2006, 243, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, R.J.; Veum-Stone, J.; Helfand, M.; et al. Outcome of hospitalized injured patients after institution of a trauma system in an urban area. JAMA. 1994, 271, 1919–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Government Accountability Office. Report to congressional committees: costs and Medicare margins varied widely; transports of beneficiaries have increased. Published October; 2012. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/assets/650/649018.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Fishman, P.E.; Shofer, F.S.; Robey, J.L.; et al. The impact of trauma activations on the care of emergency department patients with potential acute coronary syndromes. Ann Emerg Med. 2006, 48, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.C.; Chapital, A.; Burgess Uperesa, B.M.; Smith, E.R.; Ho, C.; Ahana, A. Trauma activations and their effects on non-trauma patients. J Emerg Med. 2011, 41, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA). Federal Registry. 2003, 68, 5322–5364.

- Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA). PL 99-272, Title IX, Section 9121, 100 Stat 167 (1986).

- Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989 (OBRA). PL 101-239, Section 6211(h)(2), 102 Stat 2106, 42 USC 1395dd.

- Bitterman, R.A. Providing Emergency Care Under Federal Law: EMTALA. American College of Emergency Physicians, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, J.R.; Newgard, C.D.; Mullins, R.J. Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act and trauma triage. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006, 10, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Clarifying policies related to the responsibilities of Medicare-participating hospitals in treating individuals with emergency medical conditions. Updated March; 2012. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EMTALA/Downloads/CMS-1063-F.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Southard, P. 2003 “clarification” of controversial EMTALA requirement for 24/7 coverage of emergency departments by on-call specialists, significant impact on trauma centers. J Emerg Nurs. 2004, 30, 582–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiff, R.L.; Ansell, D. Federal anti-patient-dumping provisions: the first decade. Ann Emerg Med. 1996, 28, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ansell, D.A.; Schiff, R.L. Patient dumping: status, implications, and policy recommendations. JAMA. 1987, 257, 1500–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, M.F. Patient dumping, emergency care, and public policy. J Health Soc Policy 1995, 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kahntroff, J.; Watson, R. Refusal of emergency care and patient dumping. Virtual Mentor. 2009, 11, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Menchine, M.D.; Baraff, L.J. On-call specialists and higher level of care transfers in California emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2008, 15, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitterman, R.A. EMTALA and the ethical delivery of hospital emergency services. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2006, 24, 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peth, H.A. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA): guidelines for compliance. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2004, 22, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, J.S.; Christensen, B.; McDonald, T.; et al. The financial burden of mandibular trauma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012, 70, 2124–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, N.C.; Mackenzie, E.; Teitelbaum, S.D.; Wright, D.; Anderson, C. Trauma system structure and viability in the current healthcare environment: a state-by-state assessment. J Trauma. 2005, 58, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|

© 2020 by the author. The Author(s) 2020.

Share and Cite

Pontell, M.; Mount, D.; Steinberg, J.P.; Mackay, D.; Golinko, M.; Drolet, B.C. Interfacility Transfers for Isolated Craniomaxillofacial Trauma: Perspectives of the Facial Trauma Surgeon. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2021, 14, 201-208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520962276

Pontell M, Mount D, Steinberg JP, Mackay D, Golinko M, Drolet BC. Interfacility Transfers for Isolated Craniomaxillofacial Trauma: Perspectives of the Facial Trauma Surgeon. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2021; 14(3):201-208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520962276

Chicago/Turabian StylePontell, Matthew, Delora Mount, Jordan P. Steinberg, Donald Mackay, Michael Golinko, and Brian C. Drolet. 2021. "Interfacility Transfers for Isolated Craniomaxillofacial Trauma: Perspectives of the Facial Trauma Surgeon" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 14, no. 3: 201-208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520962276

APA StylePontell, M., Mount, D., Steinberg, J. P., Mackay, D., Golinko, M., & Drolet, B. C. (2021). Interfacility Transfers for Isolated Craniomaxillofacial Trauma: Perspectives of the Facial Trauma Surgeon. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 14(3), 201-208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520962276