Introduction

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) is a chronic, insidious disease that can affect any part of the oral cavity. It may also involve the pharynx or esophagus and may precede or be associated with vesicle formation. It is always associated with juxta-epithelial inflammation, followed by fibroelastic change of the lamina propria with epithelial atrophy leading to stiffness.[

1] In 1952, Schwartz first described OSMF as a chronic, premalignant condition of the oral mucosa that can progress to malignancy when left untreated with an incidence of 4.5% to 7.6%.[

2] The disease is more common in men aged between 20 and 40 years.[

3] Although the pathogenesis of the disease is not well established, it is believed to be multifactorial. Numerous factors trigger the disease process by causing a juxta-epithelial inflammatory reaction in the oral mucosa. Common contributory factors to this chronic disease include areca nut chewing, intake of spicy food, nutritional deficiencies, genetic and immunological processes, and other factors. Presenting symptoms are burning pain, progressive inability to open the mouth, and difficulty in mastication and swallowing. Speech and hearing deficits may also occur because of involvement of the tongue and the eustachian tubes.[

1,

2]

The surgical management of OSMF, which presents with a severe degree of trismus, is a great surgical challenge. Surgical procedures for this disease include excision of fibrous bands with or without coverage of the surgically created defect. Skin or placental grafts, tongue flaps, buccal fat pad (BFP) grafts, nasolabial flaps (NLFs), and others are used for the coverage of the related defects. Additional procedures such as coronoidectomy have been described in the literature to alleviate restricted mouth opening.[

4]

In this study, the NLF and BFP for treating patients with OSMF were compared. The hypothesis was that the NLF is a more effective reconstructive option than the BFP, even in terms of extraoral scarring of the NLF. To prove the hypothesis, preoperative mouth opening (in millimeters), postoperative mouth opening (interincisal distance in millimeters—interincisal mouth opening [IIMO]), and pre- and postoperative oral commissural width (in millimeters) were compared, and the subjective and objective assessment of the extraoral scar was performed.

Methods

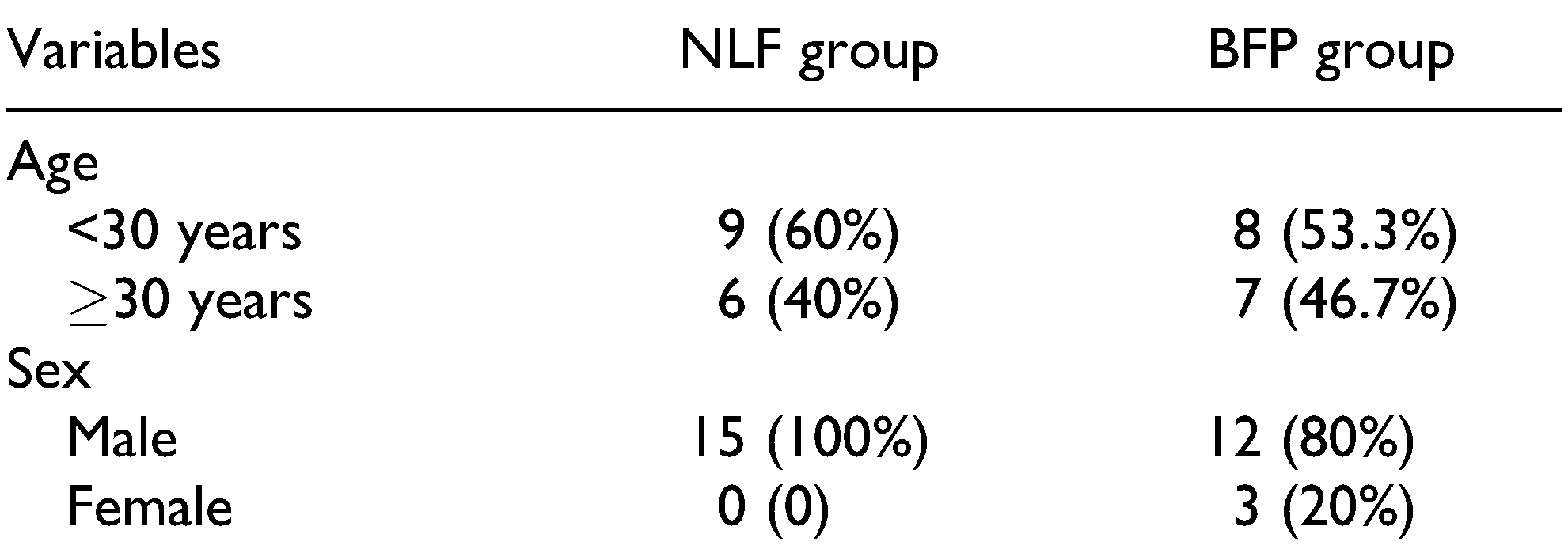

This randomized controlled study involves 30 out of the 34 patients who were treated for OSMF with excision of the fibrous band and reconstruction with either BFP or NLF at Craniofacial Centre between 2014 and 2017. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB no. 2014/P/OS/26), and all participants signed an informed consent form. The age of the patients was between 17 and 45 years (

Table 1).

The presenting complaints were reduced mouth opening, inability to chew food, palpable fibrous bands, and biopsy-proven diagnosis of OSMF.

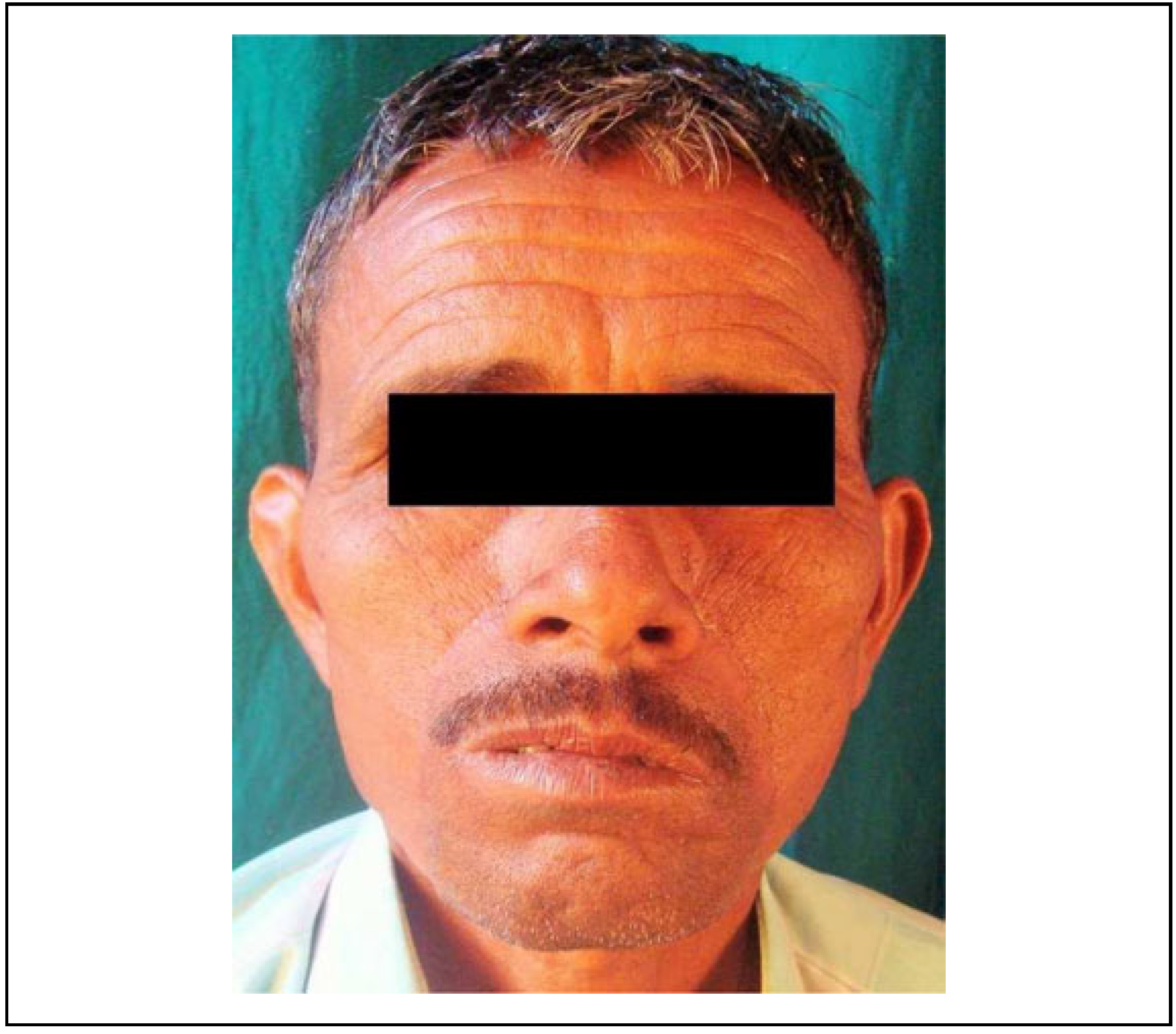

Inclusion criteria were patients with restricted mouth opening of <20 mm (stage III and IV) (

Figure 1); patients having painful ulceration, burning sensation, intolerance to spices, a habit of betel nut or tobacco chewing, and histopathological features suggestive of OSMF; and patients with regular follow-up records. Patients with an ulceroproliferative growth picked up on palpation or ultrasonography, suspected to be malignant, patients with mouth opening of more than 25 mm and a mild form of mucositis, and patients without regular follow-up were excluded from the study. Both groups were evaluated for predictor variables like preoperative interincisal mouth opening (in millimeters) and preoperative oral commissural width (in millimeters) from Chelion (the most lateral point of labial fissure) of the right side to Chelion on left side. The outcome variables were postoperative IIMO as assessed by measuring the interincisal distance in millimeters, postoperative commissural width, and extraoral scar formation as analyzed by the Stony Brook Scar Assessment Scale[

5] which is an objective assessment (

Figure 2).

Postoperatively, the patients of both groups received antibiotics and nasogastric feeding for 1 week. To prevent contracture and relapse, a physiotherapy protocol involving the wooden spatulas was started 48 hours after the surgery for 1 week, followed by physiotherapy using a Heister’s jaw exerciser. Patients were instructed and motivated to continue the physiotherapy protocol themselves for up to 6 months and were followed up for 1 year. For statistical analysis, a statistician analyzed the data using SPSS statistical software for Windows, version 8.0, through the paired and unpaired t test.

Discussion

The incidence of OSMF has increased 2-fold in the last decade and the optimal strategy for managing this disease is still under debate. Numerous materials like use of skin graft, collagen, laser surgery, cryosurgery, lingual pedicled flaps, temporalis fascia flap, platysma flap, BFP, NLF, and radial forearm free flap are documented, but there is lack of consensus about the reliable soft tissue flap.

The use of the NLF in the reconstruction of head and neck defects has proved to be effective and reliable.[

6] The BFP has been widely used for the repair of defects in OSMF with advantages and limitations compared with the NLF. The present study compares the BFP and NLF for treating patients with OSMF by evaluating their mouth opening, the postoperative commissural width, and extraoral scar formation, which were previously believed to be the substantial drawback of the NLF.

Various studies have shown areca nut, gutkha, and betel nut chewing to be the main etiologic factor for OSMF similar to the findings in this study[

4,

7,

8] OSMF is a chronic, premalignant condition of the oral mucosa that can progress to malignancy when left untreated with an incidence of 4.5% to 7.6%,[

2] although none of the patients in this study showed malignant transformation. Reduction or preferably stoppage of the habit is an essential component of the treatment plan. Periodic counseling of the patient and relatives can prove beneficial for the OSMF treatment. In the early stages, OSMF can be treated through the medicinal measures and physiotherapy, but in stage III and IV, surgery followed by physiotherapy is the management strategy.

Numerous studies have reported the use of the NLF for the closure of fibrotomy defect and the defects of the upper lip, tongue, and gingival sulcus. The versatility of this flap is attributed to its reliable vascularity derived from numerous vessels in the vicinity. It is advocated because of the ease of elevation, proximity to the defect, minimal swallowing and speech difficulties, and a relatively cosmetic result as the scar is formed in a natural crease. The BFP which has also been used for the coverage of the defect after fibrotic band excision is simple due to easy access[

9]; however, the tissue of this flap may be inadequate for the complete coverage of the defect which is the biggest disadvantage of this flap (

Figure 3). The gradual recurrence of trismus was observed due to islands of mild secondary fibrosis if aggressive physiotherapy is not performed (

Figure 4).

The use of the NLF, in OSMF treatment, is more suitable for juxtaposed defects, particularly those of the buccal mucosa.[

6] Therefore, this flap is becoming increasingly popular. The NLF is a good example of the transposition flap principle.[

10] The satisfactory result of NLF for OSMF is because flap itself is not a part of the crippled oral disease. In this study, bilateral centrally based pedicled single stage flap was used without any second surgery for revision. The literature suggests that the NLF is a superior reconstructive option for patients with OSMF in terms of blood supply, adaptability to the defect (

Figure 5), and versatility.[

3,

6,

10]

In the present study, symptoms in both groups were analyzed. The main presenting complaints were the inability to consume routine spicy food and reduced mouth opening. In our study, at 1-year follow-up, preoperative complaints persisted in 3 patients (20%) in group I (BFP). In group II (NLF), all patients were relieved of symptoms and none had the complaint of burning sensation. This may be because the NLF once transferred lacks sensory function.

Rai et al reported that the mean pre- and postoperative mouth opening was better in NLF than BFP group.[

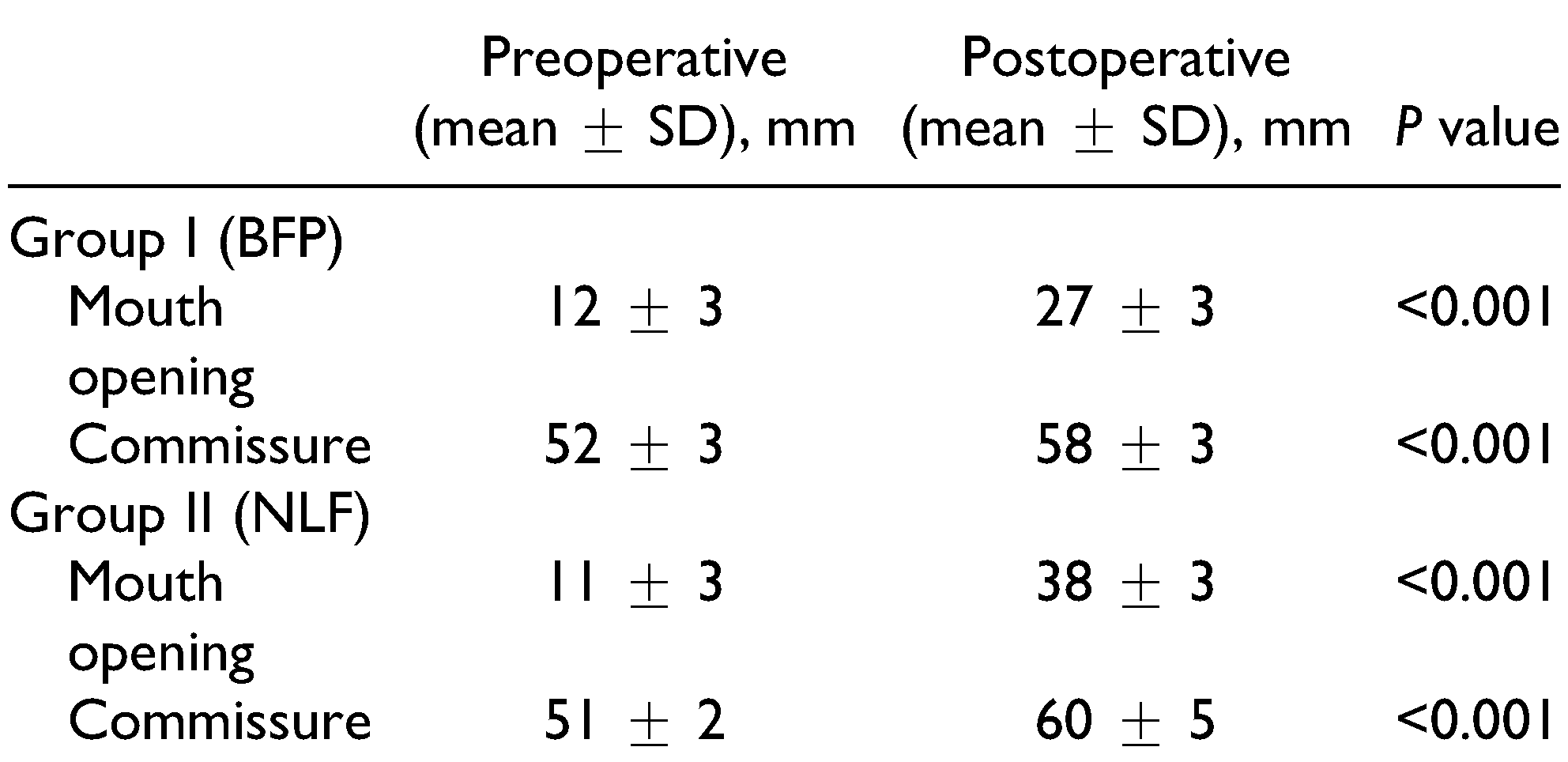

7] The present study shows similar satisfactory results with preoperative and postoperative mouth opening being 12 mm and 27 mm in group I and 11 mm and 38 mm in group II (NLF), respectively.

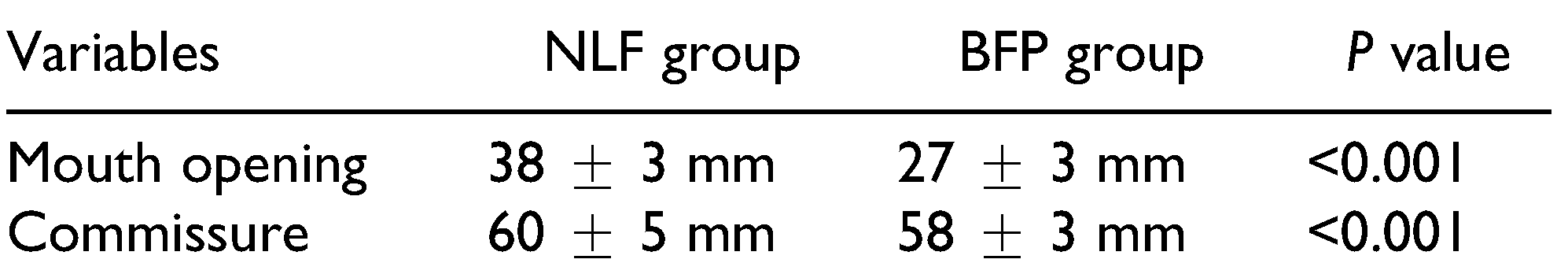

A drawback of the NLF as reported in the literature is “fish mouth” appearance due to increase in intercommissural width. In our study, we evaluated this parameter to objectively assess the changes in the intercommissural width. The preoperative and postoperative commissure width was 52.13 mm and 58 mm in group I (BFP) and 51 mm and 60 mm in group II (NLF), respectively. Thus, significant difference was observed in both groups, showed that the inter-commissural width increased in NLF group but none of patient expressed unhappiness about as compared to the mouth opening achieved. One of the major drawbacks of the BFP is its inability to cover the entire intraoral defect, particularly in the commissure area, which may lead to secondary fibrosis over a period. Other critical areas such as the retromolar trigone (RMT) region, which is the faucial area adjacent to uvula, can be covered. Thus, the BFP is more effective when the fibrous bands are localized to the RMT region. In the present study, it was found that although the mean mouth opening increased by 50 mm in group I (BFP) during the immediate postoperative period, it reduced to 27 mm during further follow-up despite strict physiotherapy guidelines as compared with 38 mm in group II (NLF).

Other studies have reported the following drawbacks of the NLF: extraoral scars and hair growth in male patients. So, in this study, we assessed extraoral scar formation and the patient’s perception. The assessment revealed a satisfactory outcome after 1-year follow-up, even though the temporary widening of oral commissure was observed. It is prudent to counsel the patient going in for NLF about the extraoral scar and weighing the benefits on a long-term basis. In our study, all patients accepted the scar without any significant complaints. The hair growth, although seen in the early postoperative period, was reduced during the follow-up period of 1 year. In NLF group, there was good coverage of raw area following fibrotomy in the early phase of post-surgery and at 1-year follow-up there was appreciable margin adaptation with no evidence of contracture with smooth pliable soft tissue in the reconstructed area. Whereas in BFP group, there was deficient coverage (25%-30%) of raw area and at 1-year follow-up there was evidence of contracture and secondary fibrosis on palpation.

Considering the advantages of the NLF over the BFP, we recommend the following surgical protocol for management of patients with OSMF:

Cessation of betel nut and tobacco chewing habits for minimum 3 months prior to surgery.

Surgical release of fibrous bands (fibrotomy) with the removal of overlying buccal mucosa.

Bilateral coronoidectomy.

Extraction of all the third molar teeth to facilitate flap in setting.

Reconstruction of the intraoral defect with the NLF.

Aggressive postoperative physiotherapy and regular follow-up.

The advantages of the NLF outweigh its drawbacks including extraoral scar formation and hair growth in male patients, which can be overcome through appropriate counseling as shown in this study.