What Surgeons Want: Access to Online Surgical Education and Peer-to-Peer Counseling—A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:Introduction

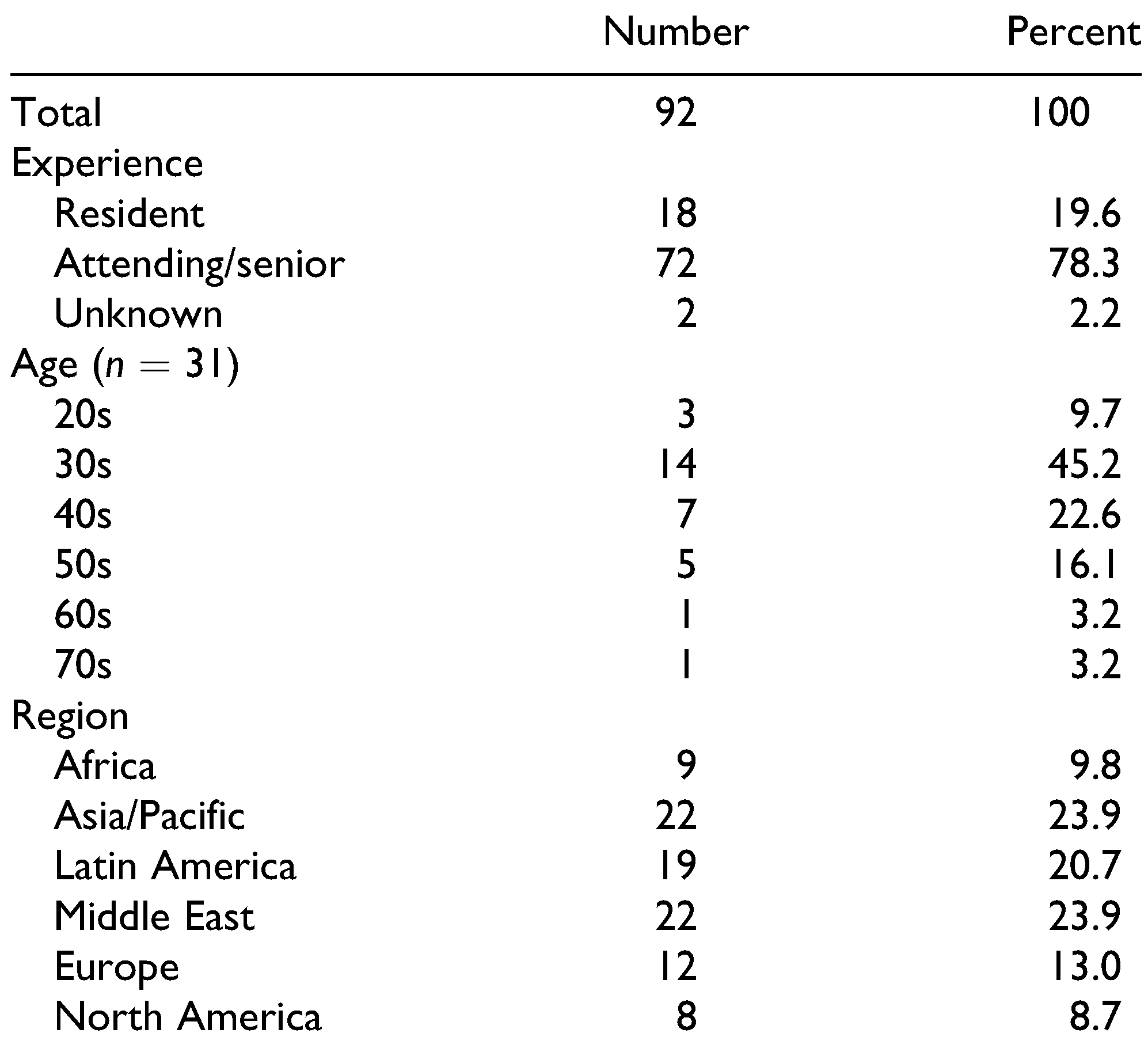

Materials and Methods

Results

Role of Technology in the Professional Careers of Surgeons

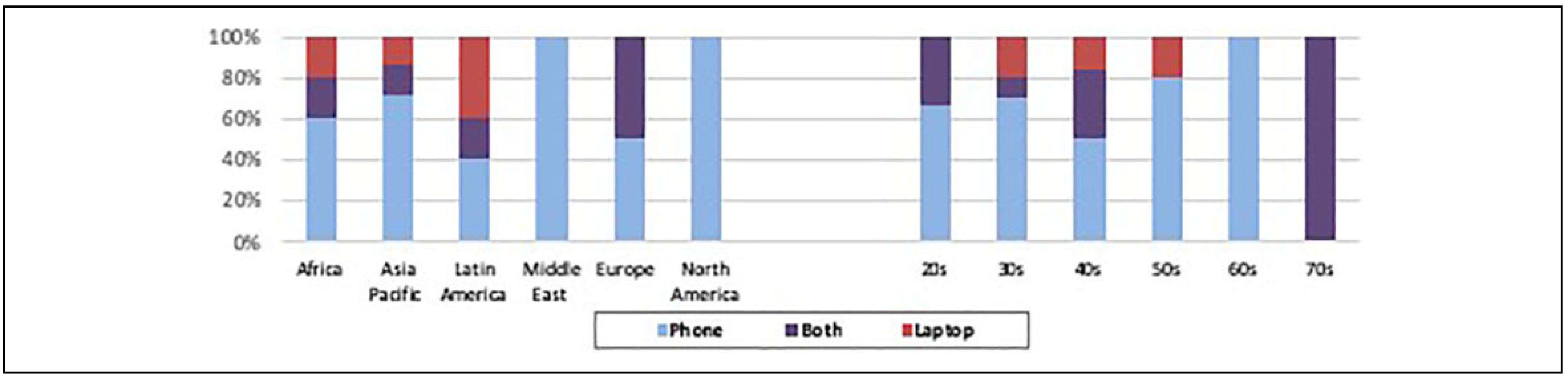

Gadget Preferences

Commonly Used Technological Resources

Variations in Use of Technology

Optimal Communication Strategies for Professional Use

- Interactive case consultation: There was an overwhelming wish (reported by 82% of participants) for interactive, real-time case consultation. The concept of interactive, real-time case consultation took many forms, such as using WhatsApp or Instagram to share images/videos and obtain feedback; e-consult systems, where questions could be easily directed to specific experts; and real-time systems to access experts for consultation immediately, even during surgery. The forums would ideally be accessible across multiple platforms and especially on mobile devices. US surgeons were less likely to want online case discussions or peer-to-peer consulting (mean AL 3.7, compared to 4.8 among surgeons from other regions). However, US surgeons and many other providers interviewed—especially those who were most senior and/or lived in highly developed countries with access to advanced surgical resources—said they would be willing to volunteer their time to answer questions and mentor younger surgeons through this type of system. A system like this would likely require organization by specialty and by region/language, with time zone coordination of “on-call” consulting surgeons to ensure real-time access. It would need to be secure and closed, with viewers and feedback identified by name and credential; numerous participants also noted that a system like this would require thoughtful attention to security and legal/liability issues, particularly for US surgeons.

- Opportunities to connect with surgeons internationally: Ultimately, the role of professional networks was paramount, with the vast majority of participants eager to connect with other surgeons in a safe, comfortable environment that would allow for a collective improvement in skills while building a supportive community. There were 3 categories in which participants encouraged increased structure and support for networking. First, WhatsApp groups were preferred by participants in all regions except North America and Europe, as it gives participants fast access to their colleagues via an encrypted platform; surgeons felt they could confidentially share information and receive a real-time response while working on a case. Second, participants requested RSS feeds, or the opportunity to set up customized notifications or emails regarding educational opportunities, new research, or other topics of interest. Anyone who was asked directly responded very favorably to the idea of having customized resources pushed to them rather than the resources being passively available if participants had the time and forethought to search. Third, surgeons across regions and especially those outside of the United States and Europe were enthusiastic to participate in a scientific and educational congress, with more than 96% of survey participants (n = 57) agreeing or strongly agreeing that they would attend. For surgeons living in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, it was particularly important to host the congress in a location close to home or to offer an online option to reduce travel costs and logistical challenges.

- 3.

- Improved online video resources: Beyond interactive case consultation opportunities, 30 participants (33%) said they desired more static and livestreaming surgical videos, including a searchable database of lectures and surgery videos. This strategy was described as an opportunity to replace the use of YouTube with similar but more professional resources, ideally with links to relevant publications. Participants repeatedly stressed the importance of a functionality to download videos for offline viewing in areas with poor internet connectivity. In addition to a surgical video platform, 36 people (39%) said they wanted more webinars and interactive-online trainings, which would offer them the opportunity to learn from people around the world without having to travel, which was often cost- or time-prohibitive. The wish for more videos was common among interviewees in their 20s and 30s. Regionally, surgeons from the United States were less likely to agree that a live surgery video platform (mean AL 3.7, compared to a mean AL of 4.7 among surgeons from other countries), or webinars (mean AL 3.7, compared to mean AL 4.7 among surgeons from other countries) would be important.

Discussion

Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators; Roth, G.A.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; et al. Global, regional, and national age-sexspecific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Disease Injury Incidence Prevalence Collaborators; James, S.L.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contini, S.; Taqdeer, A.; Cherian, M.; et al. Emergency and essential surgical services in Afghanistan: still a missing challenge. World J Surg. 2010, 34, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buren, N.C.; Groen, R.S.; Kushner, A.L.; et al. Untreated head and neck surgical disease in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional, countrywide survey. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014, 151, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrime, M.G.; Sleemi, A.; Ravilla, T.D. Charitable platforms in global surgery: a systematic review of their effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, sustainability, and role training. World J Surg. 2015, 39, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, R.A.; Gyamfi, Y.A.; Contini, S. Challenges of meeting surgical needs in the developing world. World J Surg. 2011, 35, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, L.; Collins, M. Training responsibly to improve global surgical and anaesthesia capacity through institutional health partnerships: a case study. Trop Doct. 2017, 47, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasheri, M.H.; Johnston, M.; Syed, U.M.; King, D.; Darzi, A. The uses of smartphones and tablet devices in surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Surgery. 2015, 158, 1352–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, A.K.; Healy, M.G.; Charlton, M.E.; Keith, J.N.; Rosenbaum, M.E.; Kapadia, M.R. YouTube is the most frequently used educational video source for surgical preparation. J Surg Educ. 2016, 73, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehring, K.A.; De Martino, I.; McLawhorn, A.S.; Sculco, P.K. Social media: physicians-to-physicians education and communication. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017, 10, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, M.P.; Chisholm, A.; Shulhan, J.; et al. Social media use by health care professionals and trainees: a scoping review. Acad Med. 2013, 88, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterling, M.; Leung, P.; Wright, D.; Bishop, T.F. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017, 92, 1043–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raiman, L.; Antbring, R.; Mahmood, A. WhatsApp messenger as a tool to supplement medical education for medical students on clinical attachment. BMC Med Educ. 2017, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choo, E.K.; Ranney, M.L.; Chan, T.M.; et al. Twitter as a tool for communication and knowledge exchange in academic medicine: a guide for skeptics and novices. Med Teach. 2015, 37, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.S.Y.; Leung, A.Y.M. Use of social network sites for communication among health professionals: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2018, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuwenburg, T.J.; Parker, C. Free open access medical education can help rural clinicians deliver “quality care, out there”. Rural Remote Health. 2015, 15, 3185. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, S.; Jalali, A. Social media as an open-learning resource in medical education: current perspectives. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017, 8, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandeira Rivas, A.; Riquelme Gaona, J.; A´lvarez Gallego, M.; Targarona Soler, E.M.; Moreno Sanz, C. Use of social networks by general surgeons. Results of the national survey of the Spanish association of surgeons. Cir Esp. 2019, 97, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdouse, M.; Devon, K.; Kayssi, A.; Goldfarb, J.; Rossos, P.; Cil, T.D. Using texting for clinical communication in surgery: a survey of academic staff surgeons. Surg Innov. 2018, 25, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, K.; Hansen, M.; Jackson, D.; Elliott, D. How health care professionals use social media to create virtual communities: an integrative review. J Med Internet Res. 2016, 18, e166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbuluk, A.M.; Ast, M.P.; Stimac, J.D.; Banka, T.R.; Abdel, M.P.; Vigdorchik, J.M. Peer-to-peer collaboration adds value for surgical colleagues. HSS J. 2018, 14, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britten, N. Qualitative interviews in medical research. BMJ. 1995, 311, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkan, J. Doing Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Crabtree, B., Miller, W., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mendioroz, J.; Garcia Cuyas, F.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; et al. Social networking app use among primary health care professionals: web-based cross-sectional survey. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2018, 6, e11147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Geurts, J.; Valderrabano, V.; Hu¨gle, T. Educational quality of YouTube videos on knee arthrocentesis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013, 19, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.P.; Quraishi, M.S. YouTube resources for the otolaryngology trainee. J Laryngol Otol. 2012, 126, 61–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffar, A.A. YouTube: an emerging tool in anatomy education. Anat Sci Educ. 2012, 5, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nason, G.J.; Kelly, P.; Kelly, M.E.; et al. YouTube as an educational tool regarding male urethral catheterization. Scand J Urol. 2015, 49, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, S.; Alayed, N.; Al-Ibrahim, A.; D’Souza, R. Realizing the potential of real-time clinical collaboration in maternal–fetal and obstetric medicine through WhatsApp. Obstet Med. 2018, 11, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, M.; Scott, R.E. WhatsApp in clinical practice: a literature review. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016, 231, 82–90 Available online: http://wwwncbinlmnihgov/ pubmed/27782019 (accessed on 31 May 2019). [Google Scholar]

|

© 2020 by the author. The Author(s) 2020.

Share and Cite

Häberle, A.D.; Nath, R.; Facente, S.N.; Albers, A.E.; Girod, S. What Surgeons Want: Access to Online Surgical Education and Peer-to-Peer Counseling—A Qualitative Study. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2021, 14, 189-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520929813

Häberle AD, Nath R, Facente SN, Albers AE, Girod S. What Surgeons Want: Access to Online Surgical Education and Peer-to-Peer Counseling—A Qualitative Study. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2021; 14(3):189-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520929813

Chicago/Turabian StyleHäberle, Astrid D., Riya Nath, Shelley N. Facente, Autumn E. Albers, and Sabine Girod. 2021. "What Surgeons Want: Access to Online Surgical Education and Peer-to-Peer Counseling—A Qualitative Study" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 14, no. 3: 189-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520929813

APA StyleHäberle, A. D., Nath, R., Facente, S. N., Albers, A. E., & Girod, S. (2021). What Surgeons Want: Access to Online Surgical Education and Peer-to-Peer Counseling—A Qualitative Study. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 14(3), 189-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520929813