Deformational plagiocephaly is the most common cause of abnormal infant head shapes and affects approximately 40% infants 7 to 12 weeks of age.[

1,

2] The diagnosis is often based on clinical examination. Treatment includes prevention through awareness and education, positioning and exercises and, for infants with increased risk factors for skull molding (eg, torticollis), molding with helmet therapy.[

3] This approach to the diagnosis and treatment of deformational plagiocephaly is now the standard of care; however, 30 years ago many children with deformational plagiocephaly were treated with cranial vault expansion.

The parallel evolution of the treatment of craniosynostosis and the unprecedented rise in the prevalence of deformational plagiocephaly led to the misdiagnosis and surgical intervention for a subset of children with occipital asymmetry in the 1990s. The purpose of this review is to briefly describe this phenomenon and the influence that Dr. Joseph S. Gruss had in decreasing unnecessary cranial surgeries for children with deformational plagiocephaly. We were fortunate to train under and work with Dr. Gruss from 2006 to 2018 as a craniofacial surgeon (C.B.) and a pediatrician (C.H.) on the Seattle Children’s Craniofacial team. Dr. Gruss provided multidisciplinary team members and trainees with the requisite clinical skills to accurately diagnose abnormal head shapes and reinforced the importance of collaboration among pediatric surgical and medical health care providers. It is this team-centric approach and interdisciplinary communication that ensures that patients with craniofacial anomalies receive the correct treatment within the appropriate time frame. In this review, we provide a brief historical overview of the diagnosis and management of positional plagiocephaly and the comparison with assessment for true lambdoid craniosynostosis, while highlighting Dr. Gruss’s crucial role in creating the paradigm shift in the diagnosis and management of occipital asymmetry in infants.

Infant Skull Shapes

The newborn skull includes an occipital bone, 2 parietal bones and 2 frontal bones that are separated by 6 major cranial sutures. These sutures allow the skull to mold during vaginal delivery and to expand as the brain grows. Variations from a normal head shape are typically categorized either as malformations caused by intrinsic developmental abnormalities or deformational changes due to extrinsic forces.[

4,

5]

Extrinsic forces can occur in utero, during birth, or in early infancy. Common examples of deformational changes include a “cone” head shape associated with vertex molding during vaginal birth, dolichocephaly with a prominent occipital shelf caused by prolonged breech position during pregnancy, and dolicocephaly with forehead prominence in premature infants.[

5] Head shapes caused by such mechanical forces often normalize within the first few months of life. Other examples of deformational changes associated with extrinsic forces can be seen in cultures where binding or wrapping the skull is a common practice to intentionally alter the skull shape. Evidence of this practice has been identified in prehistoric skulls as well as skulls found in North, South, and Central America and Australia. Dr. Gruss taught trainees about deformational changes by showing artwork from Native Americans from the Chinookan tribe in the Pacific Northwest of the cultural practice of using wooden slats to mold the infants’ skulls between the ages of 3 months and 1 year. Currently, the most common extrinsic cause of abnormal head shape in later infancy is deformational plagiocephaly and/or brachycephaly, which affects hundreds of thousands of infants every year.

Intrinsic causes of abnormal head shape include craniosynostosis, in which one or more of the calvarial sutures fused prematurely. Virchow described the restriction of growth perpendicular to fused sutures in patients with craniosynostosis due to cretinism giving them predictable abnormal shapes.[

6] “Classic” head shapes can be ascribed to craniosynostosis of the major cranial sutures. Scaphocephaly is the most common skull malformation, and the pattern is caused by sagittal craniosynostosis. Least common is posterior plagiocephaly due to lambdoid craniosynostosis, which represents approximately 4% to 5% of cases of single-suture synostosis.[

7]

While most causes of extrinsic deformational skull changes do not require intervention, patients with craniosynostosis often require a surgical cranial vault expansion within the first year of life.[

8] Differentiating between intrinsic and extrinsic causes of the deformity is therefore crucial to guide appropriate evaluation and management.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Craniosynostosis in the 1990s

Clinicians can often rely on a clinical history and physical examination to distinguish between an abnormal head shape caused by an extrinsic force, such as deformational plagiocephaly, versus an intrinsic force, such as craniosynostosis. Historically, clinicians were taught that a progressive skull shape abnormality in infancy was most likely related to an intrinsic process as the deformational changes associated with pre- and postnatal molding tended to resolve spontaneously.[

9] Identification of abnormal fontanelles and palpation of ridges over fused sutures is often the first indication of a malformation on examination. Recognizing classic head shapes associated with single-suture craniosynostosis can be sufficient for a skilled examiner to make an accurate diagnosis. Yet, sometimes the deformity can be subtle and radiographs can be helpful. Until the 1970s, plain film radiographs were the only tool available to help the practitioner with the diagnosis. While there are some features demonstrable on plain film (such as the harlequin eye deformity in unicoronal craniosynostosis), the resolution of plain film X-rays is insufficient to accurately and reliably make the diagnosis of premature suture fusion. With the advent of CT scans in the 1970s and 1980s, the resolution improved, but it remained difficult to discern a calvarial suture fusion with these early technologies. Slice thickness which began at 8 millimeter in the 1970s dropped to 1 millimeter in the 1980s. Yet it wasn’t until the advent of 0.5 millimeter slice thickness and high resolution 3-dimensional reconstructions in the early 2000s that one could confidently use CT scans to identify craniosynostosis. Today, some surgeons feel that CT scans are unnecessary in straightforward cases of major suture craniosynostosis,[

10] while others obtain CT scans to aid in diagnosis and surgical planning. Either way, today a CT scan can now provide detailed information about the skull morphology and cranial sutures.

The surgical correction of craniosynostosis has evolved since Lane’s description of a strip craniectomy in 1892.[

11] This initial surgery was condemned and surgical intervention for craniosynostosis did not become popular until the 1950s. For the next few decades, strip craniectomy (ie, suturectomy) was the procedure of choice despite its suboptimal results. Then, in the 1970s, Paul Tessier began to expand the surgical frontier for treating patients with craniosynostosis, and the field of craniofacial surgery was born. As confidence in the surgical treatment of craniosynostosis grew, a greater number of procedures were performed and the surgery is now considered the standard of care for most forms of craniosynostosis.[

12]

By the 1990s, the surgical interventions had become safer, more effective, and performed more widely. The resolution of CT scans was not yet adequately robust to reliably diagnose craniosynostosis and therefore most practitioners made the decision for surgery based on physical exam alone. As the specialty of craniofacial surgery was growing, a paradigm shift was occurring in the specialty of pediatrics.

The Pediatric “Back to Sleep” Campaign

One of the greatest achievements in pediatrics has been the reduction of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), which is still the leading cause of death for infants between 1 month and 1 year of age in the United States.[

13] In 1993, approximately 4700 US infants died from SIDS. Research on SIDS discovered that the risk of dying from SIDS increased by at least twofold in infants lying on prone versus supine. In 1994, the American Academy of Pediatrics introduced the “Back to Sleep” campaign in effort to educate the public about SIDS.[

13] Between 1993 and 2010, the percent of infants placed to sleep on their backs increased from 17% to 73% and the number of infants dying from SIDS has decreased to 2063 per year as of 2010.[

13]

Rise of Cranial Vault Expansions for Occipital asymmetry

During the same period that pediatricians began promoting safe sleeping practices for infants, craniofacial surgeons were seeing a rapid rise in referrals for patients with occipital asymmetry.[

14] Yet, because lambdoid craniosynostosis is relatively rare, practitioners outside of the busiest craniofacial centers would have had little experience with the nuances of its diagnosis. Prior epidemiologic investigations have demonstrated that wide variations in thresholds and methods for diagnosis and referral contribute to the variability in published estimates of occurrence of craniosynostosis.[

15] In fact, the literature from that time makes numerous references to the “non-synostotic” and the “sticky” suture indicating that unnecessary surgery was performed on patients with deformational plagiocephaly.[

16,

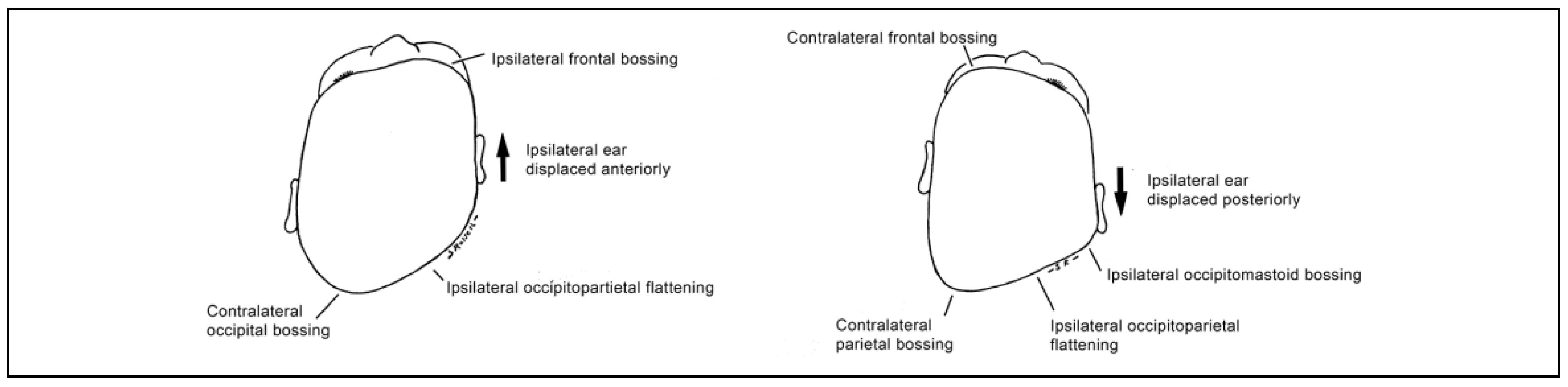

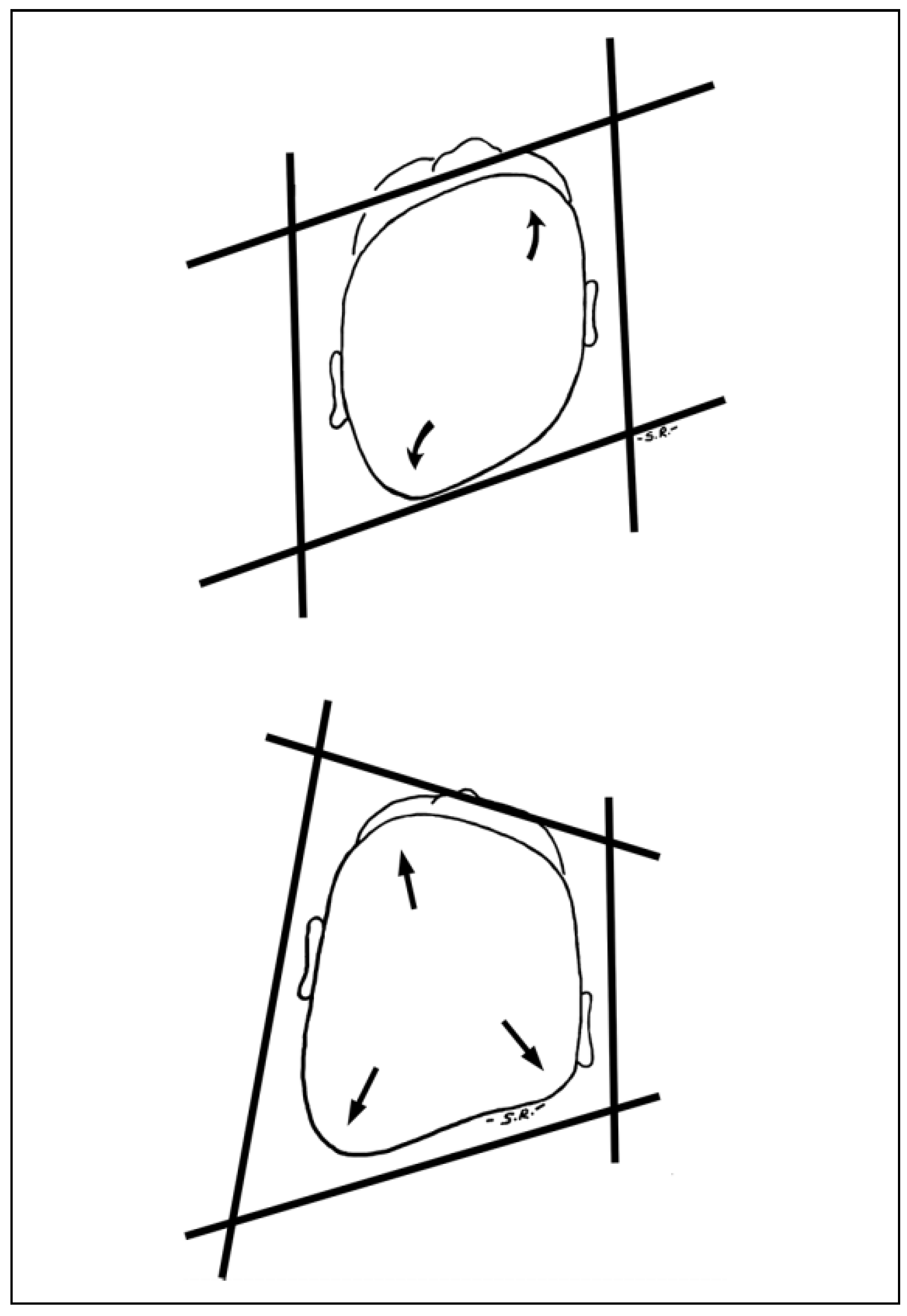

17] At this crossroads, craniofacial surgeons and neurosurgeons needed a better technique to differentiate between true lambdoid craniosynostosis and deformational plagiocephaly above and beyond a flattened occiput. This description came from the landmark paper by Dr. Gruss and his interdisciplinary colleagues which compared the trapezoidal head shape of lambdoid craniosynostosis with the parallelogram head shape of deformational plagiocephaly (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).[

18,

19] Additional clinical findings of the mastoid bulge and skull base tilt were 2 specific phenotypic traits that could be used to differentiate the two. Surgeons finally had the tools to identify true lambdoid craniosynostosis among the rising tide of patients presenting with deformational plagiocephaly. These tools became a fundamental teaching point used by Dr. Gruss to teach trainees in clinic and craniofacial surgeons from around the world at national and international conferences. A patient with lambdoid craniosynostosis could not pass through clinic without Dr. Gruss grabbing every trainee, nurse, or attending within earshot to come see the trapezoidal head shape, skull base tilt, and mastoid bulge.

Current State

Currently, the incidence of deformational plagiocephaly remains high. It is now well recognized by pediatricians thereby generating lower rates of referral to craniofacial centers and more preventative education. The treatment of deformational plagiocephaly depends on severity and includes observation, repositioning, and helmet therapy. Different centers have created various algorithms of indications for helmeting and a further understanding of the role torticollis and developmental delays play in the deformity also factor in when making helmet therapy decisions.[

3,

20,

21,

22,

23]

Alternatively, the incidence of lambdoid craniosynostosis remains quite rare, with a rate consistently between 4% and 8% of all forms of single-suture craniosynostosis. But, we now have better diagnostic tools and imaging to differentiate the two. In fact, some centers have entire clinics devoted to the diagnosis and treatment of deformational plagiocephaly, and the providers in these clinics have become so adept at diagnosing deformational plagiocephaly that they can reliably identify cases of true lambdoid craniosynostosis and then refer the patient to a craniofacial team.

The surgical treatment of lambdoid craniosynostosis has also evolved. While the switch cranioplasty has been effectively used for decades and remains the preferred technique of many surgeons, other approaches include modified surgical techniques in conjunction with helmet therapy. Additionally, as our diagnostic ability has improved, patients with true lambdoid craniosynostosis are presenting at an earlier age, giving surgeons a wider variety of interventional options.[

24] Additionally, the association between lambdoid craniosynostosis and Chiari malformations has led some to prophylactically decompress the foramen magnum in hopes to reduce symptomatic Chiari malformation.[

25] The surgical treatment of lambdoid craniosynostosis continues to evolve as our ability to accurately diagnose the condition improves.

Conclusion

The intersection of rising rates of deformational plagiocephaly, reliance on traditional teaching that a clinical history of worsening deformity is indicative of a malformation, rudimentary imaging modalities, and increased surgical capacity likely lead to an increase in unnecessary surgery on patients with abnormal head shapes caused by recommendations for supine sleep for all infants. Fortunately, in response to this convergence, Dr. Gruss and his collaborators provided critical diagnostic criteria for differentiating between the surgical diagnosis of lambdoid craniosynostosis and the nonsurgical diagnosis of positional plagiocephaly saving countless infants from being subjected to unnecessary surgery.

Although the clinical distinction between deformational plagiocephaly and lambdoid craniosynostosis is now routine, the lessons that Dr. Gruss taught us apply to many other areas of craniofacial care. An example is the diagnostic challenge between metopic ridging due to physiological closure of the metopic suture in infancy and true metopic craniosynostosis. In this case, the improved fidelity of CT scans in detecting a closed metopic suture adds no benefit to the accuracy of the diagnosis since this suture is known to fuse normally between 2 and 24 months of age.[

26] However, we as a community have further work to do to develop consensus on the diagnostic criteria for metopic craniosynostosis.[

27,

28] We will continue to learn from one another and apply the questioning/reevaluation of current practice and partnership with craniofacial surgeons and pediatric providers to continue to answer these questions.

Dr. Gruss was a committed member of the Seattle Children’s Craniofacial Center for over 20 years. He was dedicated to the concept of team care for children with congenital craniofacial conditions and this was evident in everything that he did. It’s Dr. Gruss’ strong collaboration with pediatrics that led to co-directorship with both medical and surgical directors of the Craniofacial Center at Seattle Children’s Hospital and its continued emphasis on holistic team care.[

29] Dr. Gruss played a fundamental role in our training as a craniofacial surgeon and pediatrician, respectively, and was the mentor to us all. As we celebrate his accomplishments, we also celebrate the values that he stood for which include continued collaboration with craniofacial surgeons and pediatricians.

Dr. Joseph Gruss was widely known in the international craniofacial community for his work in trauma surgery. For members of the Seattle Craniofacial Center, he will be remembered for his passion for teaching, commitment to acknowledging where the gaps are in our current practice, and dedication to collaboration with colleagues to provide holistic team care.