Results

A total of 432 patients underwent surgery for zygomaticoorbital trauma in 8-year study period. There was a mean follow-up period of 4.7 years, with 65% of cases followed up for 4 or more years, and 97% of cases followed up for minimum of 12 months postoperatively, with a minimum of 3 months; 92% of cases treated in this period were male, with just 34 cases involving female patients. The average age of patients in the study period was 36 years (range 16-87 years). In our region, children are treated in a dedicated Children’s Hospital and are therefore not included within the scope of this article.

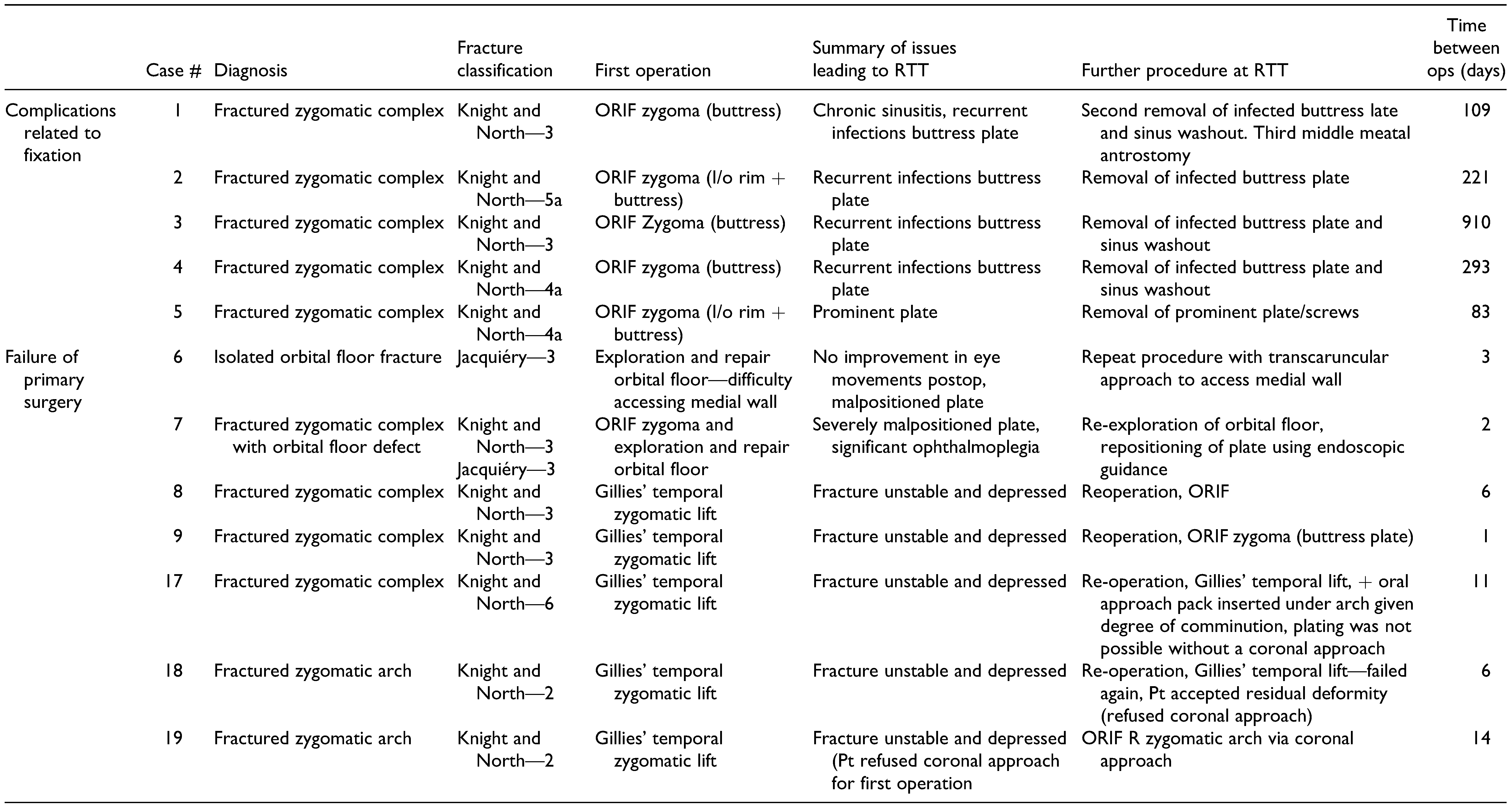

In total, 116 cases were treated with closed reduction and 316 with open reduction and internal fixation; 20 cases were identified as having returned to theatre for reoperation (see

Table 1). There were no significant differences between those requiring repeated surgery and those who did not in terms of fracture pattern or grade of operating surgeon (consultant vs. trainee). The average age of the return to theatre group was also 36 years, with a range of 21 to 82 years. All patients who required reoperation were male.

Five patients required removal of fixation, 4 of which were due to infection. Patients who had a buttress plate placed were significantly more likely to develop an infection than those who had open reduction and internal fixation without an oral approach (Fisher exact P = .042).

Seven patients required reoperation within 2 weeks of the primary procedure. Five of these were failures of initial attempts at closed reduction, with instability of the fractures resulting in repeated displacement, while 2 were due to inadequate fracture reduction at the initial open reduction and internal fixation.

Seven patients developed late deformity requiring delayed further surgery (mean 313 days after primary surgery). Five of these had late development of enophthalmos and hypoglobus, while 2 had late soft tissue atrophy leading to flattening and asymmetry.

One patient sustained a further injury displacing the original fracture and requiring repeat surgery.

Discussion

In South Yorkshire, all patients with midface or zygomatico-orbital trauma are assessed according to a regional protocol with follow-up dependent on clinical urgency. Those with clinical muscle entrapment or reduced visual acuity detected by the referring physician are evaluated immediately; those with displaced fractures, trismus, globe displacement, diplopia, or altered facial sensation are reviewed within 72 hours; and those with radiographic signs of injury but no clinical signs are reviewed within 2 weeks. Decisions regarding specific timing and nature of surgery, including approach, utilization of 3-dimensional planning, or navigation, are at the discretion of the operating surgeon.

Previous reviews of orbital trauma complications have focused on areas such as biomaterials [

3] and timing [

4] in relation to outcomes, and there is little in the literature regarding those with posttraumatic, postsurgical poor outcomes requiring further surgery. Wolfe et al. [

5] evaluated 240 such patients in the setting of a single surgeon’s referral practice with a wide range of midfacial trauma requiring reoperation but included an additional 77 patients undergoing primary surgery. They describe indications for repeat surgery but did not draw any conclusions about the reasons for failure of the primary procedures. The most common symptom in those having repeated surgery in their series was enophthalmos (47%), with malar flatness close behind (33%).

In our series, 4 main themes were identified in those patients who required reoperation: complications related to fixation materials, failure of the initial surgery, development of delayed deformity, and reinjury (see

Table 1).

Of those having complications related to fixation materials, 1 patient requested removal of an infraorbital plate as it was palpable and causing anxiety. The 4 who had infection all did so in plates placed via an oral approach, which is unsurprising given the exposure of the metalwork to the oral bacterial flora at the time of insertion. The overall rate of hardware removal due to infection in our series is low (0.9% requiring hardware removal due to infection), a previous systematic review of the removal of hardware placed in the treatment of trauma found that 3.5% of cases resulted in hardware removal due to infection. [

6] In all cases, the fractures had fully united before the requirement for removal of metalwork, and no further fixation was required.

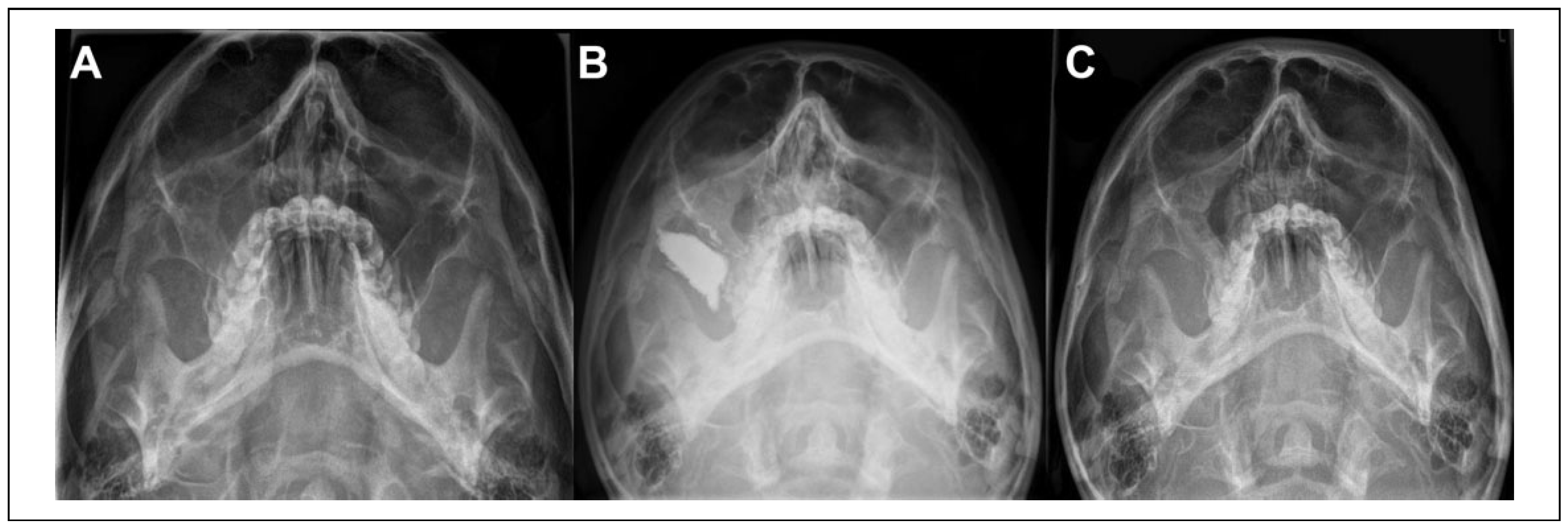

Seven patients required reoperation within 2 weeks of their primary procedure. We consider these to represent failure of the initial surgery. Five had undergone a “closed” approach with zygomatic elevation via a Gillies’ temporal approach and no fixation. Three required open reduction and internal fixation, while 2 refused open reduction. Both of these patients underwent a further elevation, one accepting the residual deformity while the other was treated with an antral pack to provide stability (

Figure 1) and achieved a satisfactory outcome.

The 2 patients who underwent primary open reduction and internal fixation and required return to theatre warrant further review.

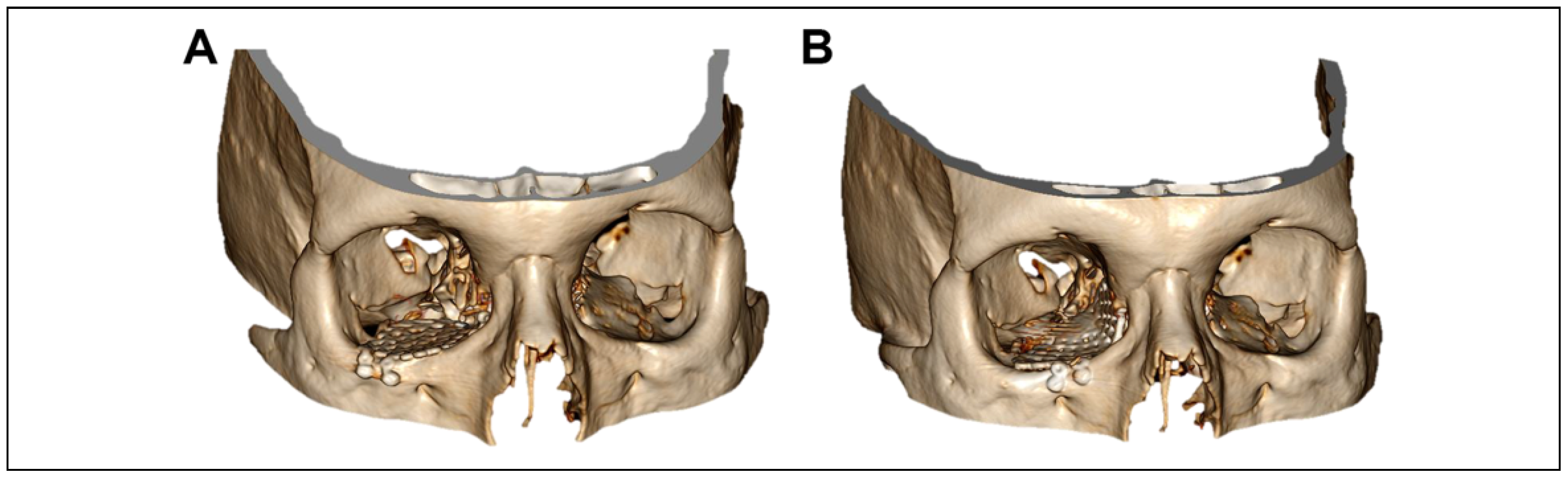

In 1 case, the fracture involved a significant part of the medial orbital wall and having restored the contour of the orbital floor, forced duction revealed residual muscular tethering. The surgery was abandoned with the floor repaired, with a plan to return to theatre for a navigationassisted transcaruncular approach to the medial wall as a joint case with oculoplastic ophthalmic colleagues (see

Figure 2). The patient was notified immediately postoperatively and returned to theatre 3 days later for the planned procedure.

In the other case, a large lateral and orbital floor defect was inadequately reduced, with difficulty obtaining optimal position of the orbital plate and residual entrapment of the ocular muscles. Postoperative imaging demonstrated malposition of the plate and the patient returned to theatre 2 days later, with endoscopic guidance via the maxillary antrum to confirm adequate plate positioning.

In both cases, a satisfactory outcome was achieved following the second procedure.

This group of patients demonstrate that satisfactory outcomes can be achieved for almost all patients with zygomatico-orbital trauma, provided that adequate exposure can be achieved, and occasionally necessitating the use of navigation or other adjuncts (such as endoscopic approaches) to provide on-table confirmation of position. Navigation is available at the discretion of the individual surgeon planning the case, whereas intraoperative CT which may have a role in such situations is not available in our institution at present.

Development of late enophthalmos is a well-recognized complication after orbital surgery [

7] and occurred in 2 cases in our series (see

Table 1, cases 14 + 16). Of note, neither patient who developed late enophthalmos had orbital reconstruction as their initial procedure, having both undergone surgery on the zygoma. Soft tissue atrophy resulting in malar flatness following trauma is less well understood. [

8] This subset of patients were treated with patient-specific implants and had satisfactory outcomes.

As interpersonal violence is the most common cause of facial trauma in the United Kingdom, [

9] it was surprising that only 1 patient required repeat surgery due to re-injury, and in that patient the mechanism was accidental collision with a door-frame, not related to interpersonal violence.

There are several limitations to our study. It is a retrospective analysis, and as such our ability to fully evaluate the decision-making process for those requiring reoperation is limited to a review of the clinical records. A prospective review would however prove challenging given the low incidence. In addition, due to the retrospective nature of this study, there are patients who have been operated on within the study period (2011-2019) who have been treated more recently than others, the mean duration of follow-up is 4.7 years. Therefore, it is possible that there may be a small number of patients who ultimately develop delayed deformity due to soft tissue changes long term, who have not currently been represented here. Further to this, we were only able to identify patients who returned to theatre in our institution. It is possible that some patients may have gone on to have surgery elsewhere, but we would expect such numbers to be small, as our institution is a Major Trauma Centre and provides services over a wide geographical area.

Overall while the need for repeated surgery in patients with zygomatico-orbital trauma is low, in some cases, it may reflect failure of conservative treatment, and a low threshold for open reduction and internal fixation may be warranted where optimal reduction and/or fracture stability cannot be achieved through a closed approach.