AO CMF International Task Force Recommendations on Best Practices for Maxillofacial Procedures During COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:Executive Summary

- Surgical procedures involving the nasal–oral muco- sal regions increase the risk of infection for medical personnel due to the aerosolization of SARS-CoV-2.

- Asymptomatic patients may be infected with SARS-CoV-2.

- Decisions should be taken locally, as factors vary by location; this includes incidence, prevalence, patient and staff risk factors, community needs, resource availability, and personal protective equip- ment (PPE). It is imperative to accurately determine the disease burden and curve trajectory.

- During times of potentially high incidence, elec- tive procedures and routine ambulatory visits should be canceled, until guidance is provided by government or hospital officials, and professional organizations permitting reopening for elective clinical services.

- Appropriate PPE should be worn during surgical procedures and ambulatory visits, which may include FFP2/N95 and full-face shield or controlled air-purifying respirators (CAPR) or powered air- purifying respirators (PAPR).

- Intraoperative measures which limit the generation of aerosolized particles that may harbor virus are recommended.

- Procedures (eg oncologic) in which a worse out- come is expected if surgery is delayed more than 6 weeks should be performed with appropriate PPE and testing, if available.

Background

General Comments/Observations

Personal Protective Equipment

- Standard PPE is a surgical cap and mask, gloves, gown, and eye protection.

- Special PPE is minimum requirement FFP2/N95 mask plus face shield or goggles (or mask with attached shield over FFP2/N95), gloves, nonporous gown, disposable surgical cap.

- Enhanced PPE is minimum requirement FFP3 mask plus face shield, gloves, nonporous gown, disposa- ble hat. Alternatively, PAPR/CAPR can be used.

Specific Recommendations

Airway Management

- Decision-making in tracheotomy should take into consideration the surgical and ICU team’s discretion as well as institutional policy.

- Avoid tracheotomy in COVID-19 positive or sus- pected patients during periods of respiratory instability or heightened ventilator dependence.

- Tracheotomy can be considered in patients with sta- ble pulmonary status but should not take place sooner than 2-3 weeks from intubation and, preferably, with negative COVID-19 testing.

- Adhere to strict donning and doffing procedures based on institutional protocol.

- Limit the number of providers participating in tracheot- omy procedure and post-procedure management.

- Perform the entire tracheotomy procedure under complete paralysis.

- Rely on cold instrumentation and avoid monopolar electrocautery.

- Advance endotracheal tube (ETT) and cuff safely below the intended tracheotomy site and hold respirations while incising trachea.

- Minimize tracheal suctioning during procedure to reduce aerosolization.

- Choose cuffed, nonfenestrated tracheotomy tube.

- Maintain cuff appropriately inflated postoperatively and attempt to avoid cuff leaks.

- Avoid circuit disconnections and suction via closed circuit.

- Place a heat moister exchanger with viral filter or a ventilator filter once the tracheotomy tube is discon- nected from mechanical ventilation.

- Delay routine postoperative tracheotomy tube changes until COVID-19 testing is negative.

CMF Trauma

- Consider closed reduction with self-drilling Mandibular Maxillary Fixation (MMF) screws.

- Scalpel over monopolar cautery for mucosal incisions.

- Bipolar cautery for hemostasis on lowest power setting.

- Self-drilling screws for monocortical screw fixation.

- When drilling is required, limit or eliminate irrigation.

- If drilling is required, consider a battery powered low speed drill.

- If a fracture requires ORIF, consider placement of MMF screws intra-orally, then place a bio- occlusive dressing over the mouth, and use a trans cutaneous approach rather than an extended intraoral approach.

- If osteotomy is required, consider osteotome instead of power saw.

Midface Fractures

- Consider closed reduction alone if fracture is stable following reduction.

- Consider using Carroll-Girard screw for reduction, and avoid intra-oral incision, if 2-point fixation (inferior orbital rim and zygomatic-frontal (ZF)) is sufficient for stabilization.

- Scalpel over monopolar cautery for mucosal incisions.

- Avoid repeated suctioning/irrigation.

- Bipolar cautery for hemostasis on lowest power setting.

- Self-drilling screws preferred.

- If osteotomy is required, consider osteotome instead of power saw or high-speed drill.

Upper Face Fractures/Frontal Sinus Procedures

- Consider delay of nonfunctional frontal bone/sinus fractures.

- Endoscopic endonasal procedure and the associated instrumentation (power micro debriders) carry a very high risk of aerosol generation and should be avoided if possible.

- When stripping of the mucosa is necessary, minimize the use of high-speed burr or power equipment.

- Avoid repeated suctioning/irrigation.

- Bipolar cautery for hemostasis on lowest power setting.

- Self-drilling screws preferred.

- If osteotomy is required, consider osteotome instead of power saw.

Oncologic Care (International Recommendations)

- Cases in which a worse outcome is expected if sur- gery is delayed more than 6 weeks, for example, squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, oro- pharynx, larynx, hypopharynx.

- Cancers with impending airway compromise.

- Papillary thyroid cancer with impending airway compromise, rapidly growing, bulky disease.

- High grade or progressive salivary cancer.

- T3/T4 melanoma (see new recommendations for treatment of melanoma).

- Rapidly progressing cutaneous Squamous Cell Car- cinoma (SCC) with regional disease.

- Salvage surgery for recurrent/persistent disease.

- High grade sino-nasal malignancy without equally efficacious nonsurgical options.

Advice Concerning Dental Procedures (Adapted From AAOMS 3/17/2020)

- Emergency and urgent care should be provided in an environment appropriate to the patient’s condi- tion, and with appropriate PPE. Remember that any procedure involving the oral cavity is considered high risk.

- Asymptomatic patients requesting removal of disease-free teeth with no risk of impairment of the patient’s condition or pending treatment should defer treatment to a later date.

- Asymptomatic patients, patients under investi- gation, and patients tested positive for COVID-19, who have acute oral and maxillofa- cial infections, active oral and maxillofacial dis- ease, should be treated in facilities where all appropriate PPE, including FFP2/N95 masks, are available.

- Patients with conditions in which a delay in surgical treatment could result in impairment of their condi- tion or impairment of pending treatment (eg, impairment of the restoration of diseased tooth when another tooth that is indicated for removal prevents access to the diseased tooth) should be treated in a timely manner if possible.

Advice on Resumption of Elective Surgical Practice

Funding

Authors’ Note

Conflicts of Interest

Other Resources

- HN Cancer Care Guidelines During COVID-19 Epidemic, Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

- University of Stanford Commentary on Nasal Procedures in the COVID-19 Era (Stanford University SOM, Departments of Oto-HNS and Neurosurgery, March 2020).

- Integrated infection control strategy to minimize nosocomial infection of coronavirus disease 2019 among ENT healthcare workers (Journal of Hospital Infection, February 22, 2020).

- Guidance for Surgical Tracheostomy and Tracheost- omy Tube Change During the COVID-19 Pandemic (ENT UK, March 19, 2020).

- British Association of Head and Neck Oncologists— Statement on COVID-19 (BAHNO, March 17, 2020).

- Guidance for ENT surgeons during the COVID-19 pandemic (Australian Society of Oto HNS, March 20, 2020).

- Managing Cancer Care During the COVID-19 Pan- demic: Agility and Collaboration Toward a Com- mon Goal (Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, March 15, 2020).

- Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. The Lancet, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140- 6736(20)31182-X

Appendix A

- SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in the community (x)

- Filtering effectiveness of the surgical mask (y)

- False negative rate of the test (z)

References

- Zou, L.; Ruan, F.; Huang, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Doremalen, N.; Bushmaker, T.; Morris, D.H.; et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS- CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 1564–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Infection Control > Environmental Infection Control Guidelines > Part IV. Appendices > Appendix B. Air > Airborne Contaminant Removal > Table B. 1. ACH and time required for airborne-containment removal by efficiency. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/environmental/appendix/air.html.

- Tracheotomy Recommendations During the COVID-19 Pan- demic. American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. Available online: https://www.entnet.org/content/tracheotomyrecommendations- during-covid-19-pandemic.

- HN Cancer Care Guidelines During COVID-19 Epidemic, Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

- Mehanna, H.; Hardman, J.C.; Shenson, J.A.; Abou-Foul, A.K.; Topf, M.C. Recommendations for head and neck surgical oncology practice in a setting of acute severe resource constraint during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e350–e359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2020 by the author. The Author(s) 2020.

Share and Cite

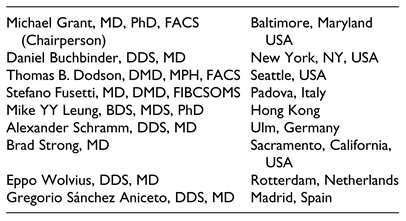

Grant, M.; Buchbinder, D.; Dodson, T.B.; Fusetti, S.; Leung, M.Y.Y.; Aniceto, G.S.; Schramm, A.; Strong, E.B.; Wolvius, E. AO CMF International Task Force Recommendations on Best Practices for Maxillofacial Procedures During COVID-19 Pandemic. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2020, 13, 151-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520948826

Grant M, Buchbinder D, Dodson TB, Fusetti S, Leung MYY, Aniceto GS, Schramm A, Strong EB, Wolvius E. AO CMF International Task Force Recommendations on Best Practices for Maxillofacial Procedures During COVID-19 Pandemic. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2020; 13(3):151-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520948826

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrant, Michael, Daniel Buchbinder, Thomas B. Dodson, Stefano Fusetti, Mike Yiu Yan Leung, Gregorio Sánchez Aniceto, Alexander Schramm, Edward Bradley Strong, and Eppo Wolvius. 2020. "AO CMF International Task Force Recommendations on Best Practices for Maxillofacial Procedures During COVID-19 Pandemic" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 13, no. 3: 151-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520948826

APA StyleGrant, M., Buchbinder, D., Dodson, T. B., Fusetti, S., Leung, M. Y. Y., Aniceto, G. S., Schramm, A., Strong, E. B., & Wolvius, E. (2020). AO CMF International Task Force Recommendations on Best Practices for Maxillofacial Procedures During COVID-19 Pandemic. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 13(3), 151-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520948826