Abstract

The fractures of the mandibular condyle are commonly encountered in maxillofacial surgical practice. The controversies to open or not to open are still ongoing. We have used both techniques, to successfully manage our patients. Open treatment of condyle fracture with or without dislocation is technically challenging. We used a “Direct Transparotid” approach in treating 13 condyle fractures over a period of 4 years. The patients were evaluated for facial nerve injury, salivary fistula, scar, function, and occlusion over a period of 12 months. There were no major complications with acceptable scar, both intraoperatively and postoperatively. The script aims at presenting our experience of direct transparotid approach surgical technique.

Introduction

The condylar fracture, condylar neck fracture, and subcondylar fractures account for 17.5% to 52% of all mandibular fractures.[1,2] Since the first condyle neck surgery was performed in 1925,[3] controversy over how to treat mandibular condyle fracture, via closed reduction versus open surgical reduction, has existed. Whether to use open or closed procedures depends on surgeons’ preferences and levels of skill and experience,[4] as well as the location of the fracture site and the severity of displacement.[5] The direct transparotid approach is considered to be an easy way to gain direct access to fractures of the mandibular ramus and condylar neck, allowing anatomical reduction and fixation with mini-plates.[6]

During a period of 4 years of our clinical practice, we performed open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) of 13 mandibular condyle fractures. Our inclusion criteria are fracture condyle with displacement, fracture dislocation, condylar neck fracture, and low condyle fracture. A “direct transparotid” approach was used and we achieved satisfactory outcomes. The purpose of this script is to introduce a simple technique for any type of complex condyle fracture and to evaluate its surgical outcome.

Methods

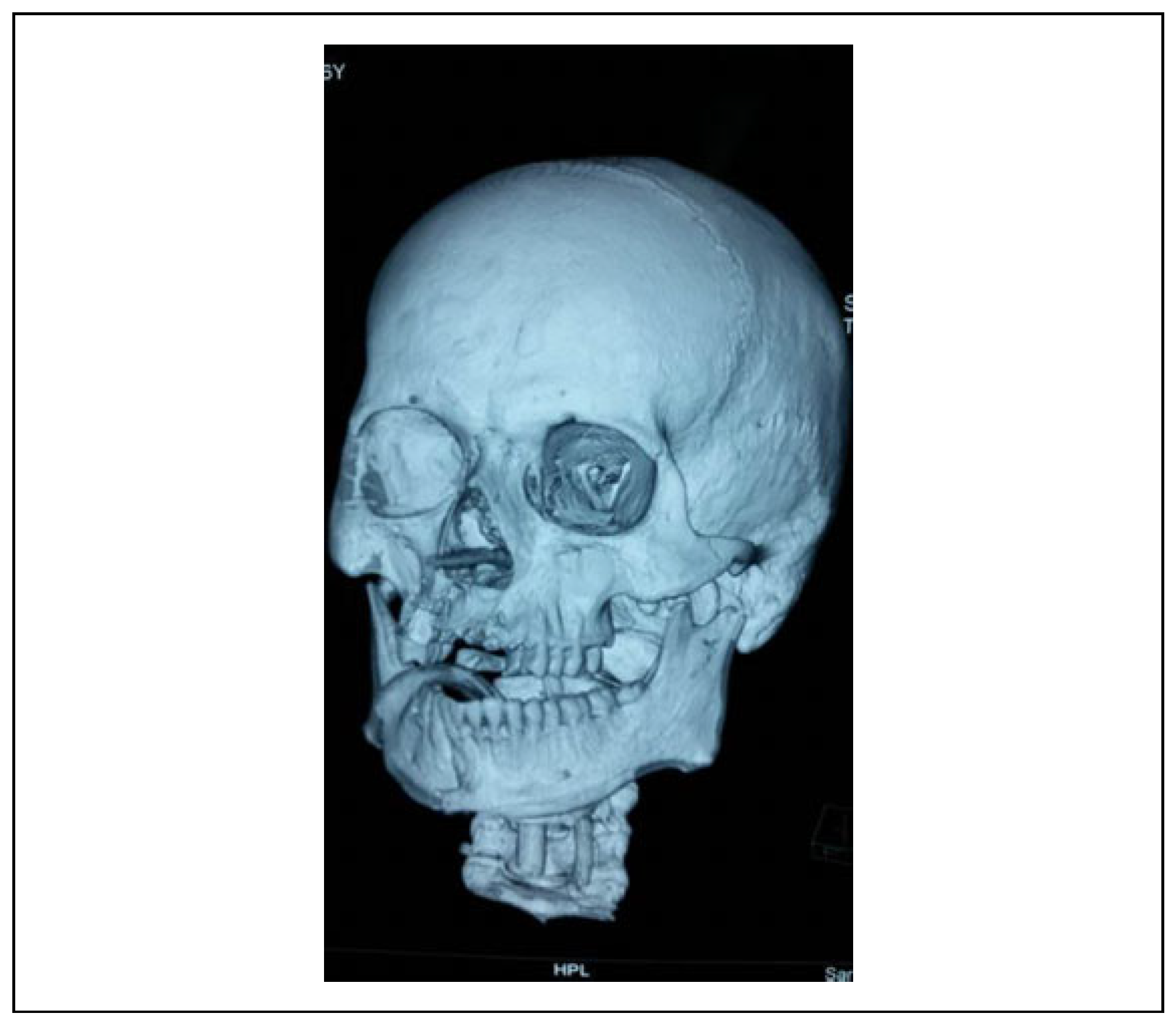

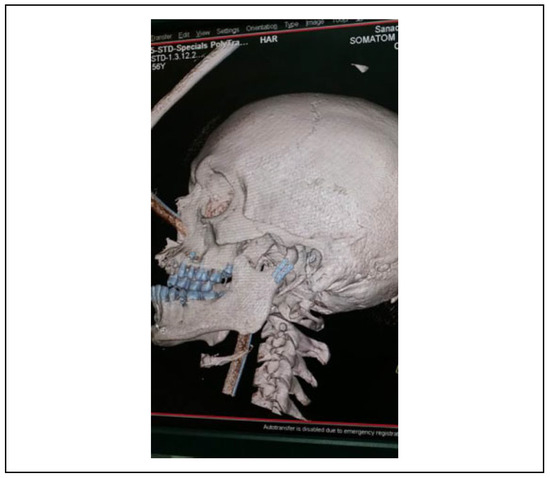

ORIF of condyle was done on 10 patients (13 condyles) using “direct transparotid” approach in our oral and maxillofacial surgery clinic between February 2014 and February 2018. All our patients were male, aged between 15 and 42 years. They were categorized into 7 unilateral condyle fractures and 3 bilateral condyle fractures. Out of the 10 patients, 7 had associated mandibular or multiple facial fractures. Majority of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) fractures were associated with fracture dislocation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CT scan of fractured condyle with dislocation. CT indicates computed tomography.

An informed signed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients whose images were used for illustrative purposes related to this study report understood and agreed to permit this use of images without patient identification.

The diagnosis was based on clinical and radiological examination after collecting patient’s history. Maxillofacial computed tomography was used preoperatively. Plain radiographs were preferred for the postoperative evaluation.

Technical Notes

All patients were operated under general anesthesia, most were nasal intubations. Patients with Panfacial fracture, base of skull fractures, or NOE fractures were intubated via submental approach or by tracheostomy.

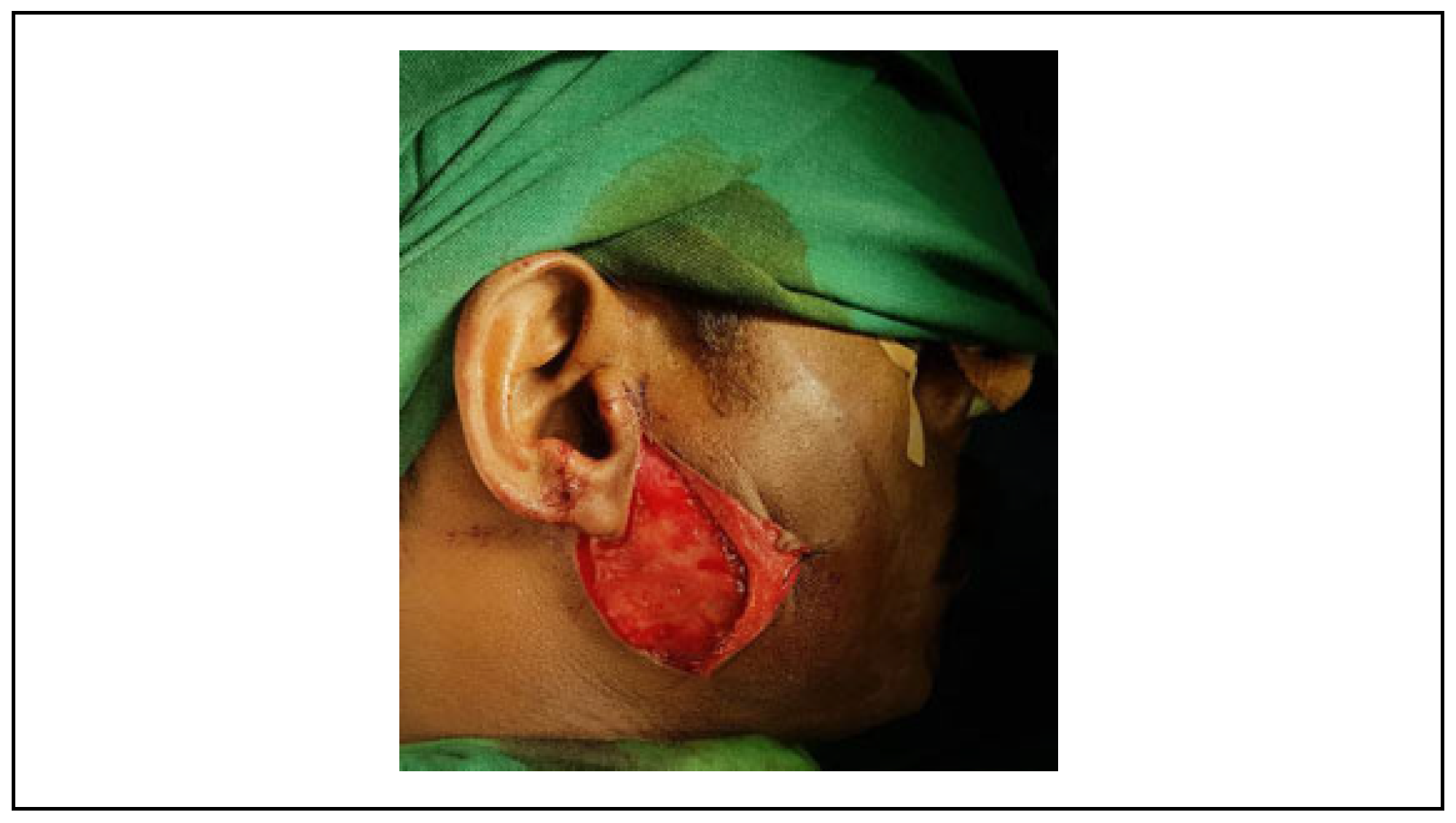

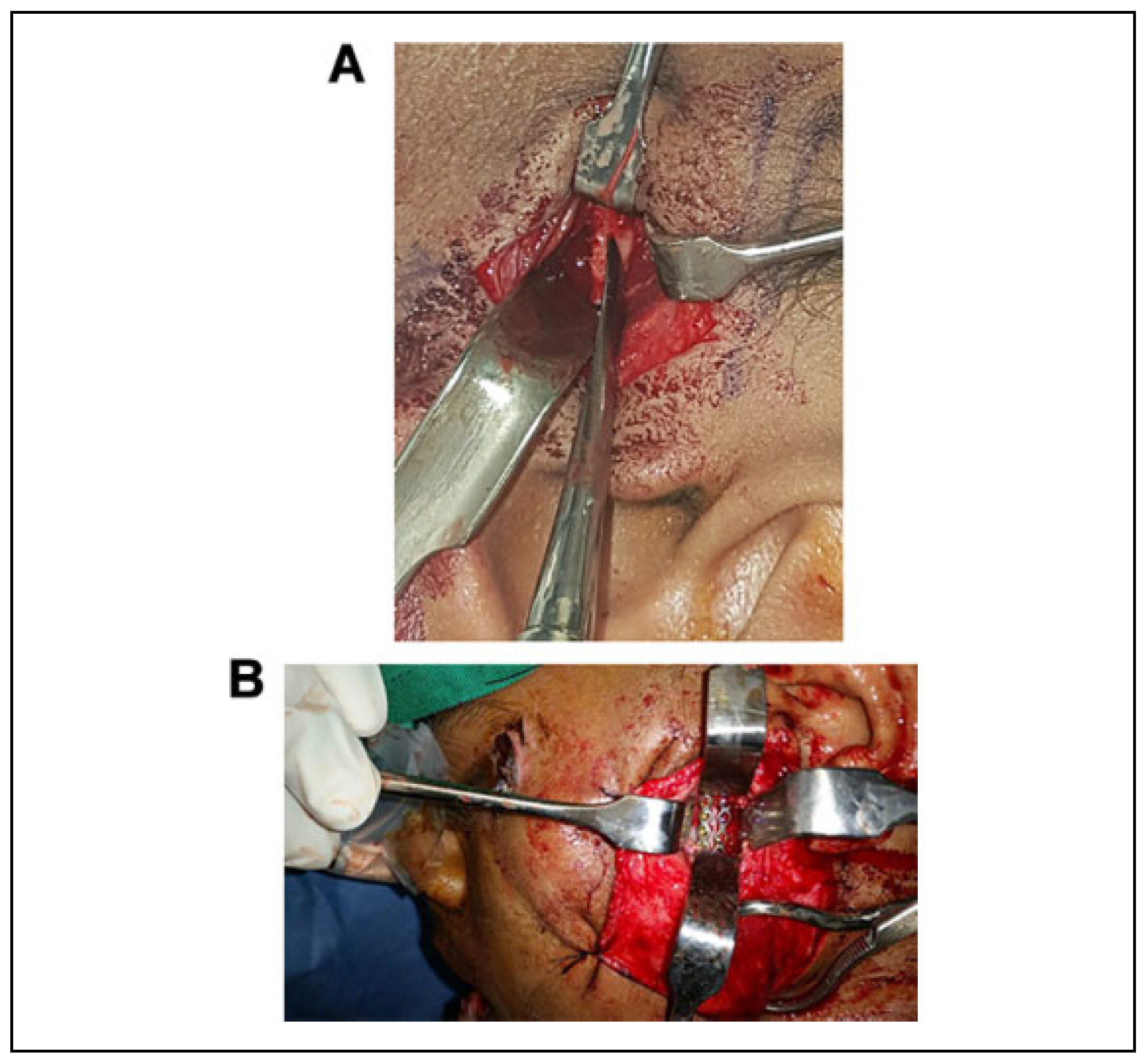

A longitudinal incision was made along the skin on the surface of the mandibular condylar neck and was extended beyond the earlobe according to the degree of skin laxity to release the tension (Figure 2). After initial incision, the skin was released from the underlying tissue in a plane superficial to the parotid capsule (Figure 3). The parotid capsule was incised parallel to the facial nerve branch axis (transverse/horizontal incision on parotid capsule) (Figure 4). Blunt dissection using a heavy hemostat in perpendicular direction directly to the ramus was carried out between the trunks of buccal and zygomatic branches of facial nerve. Blunt dissection was carried out by opening of the beaks of the hemostat perpendicular to the long axis of the facial nerve branches and no closure of hemostat was done when within the tissue to avoid injury to vital structures to expose the fascia masseterica. Once beyond the masseter muscle, cautery with low intensity was used to incise the muscle and periosteum, and the fracture site was exposed. This allowed for direct vision with adequate exposure. There will be no bleeding or major vessel encountered in this region. The proximal part of the mandibular ramus was pulled down to obtain reduction of the condylar head. Two 4-hole mini-titanium plates were applied to the fracture site of the mandibular condylar neck for rigid fixation (Figure 5). The occlusal relationship was checked. Surgical drains were never placed. Layered suture closure was carried out. Watertight closure of the parotid fascia was strictly followed.

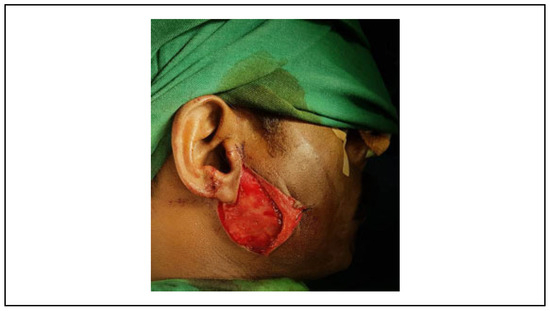

Figure 2.

Incision marking.

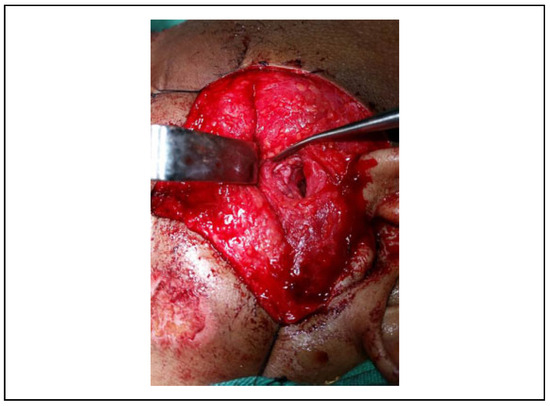

Figure 3.

Skin Flap with exposure of parotid fascia.

Figure 4.

Transparotid.

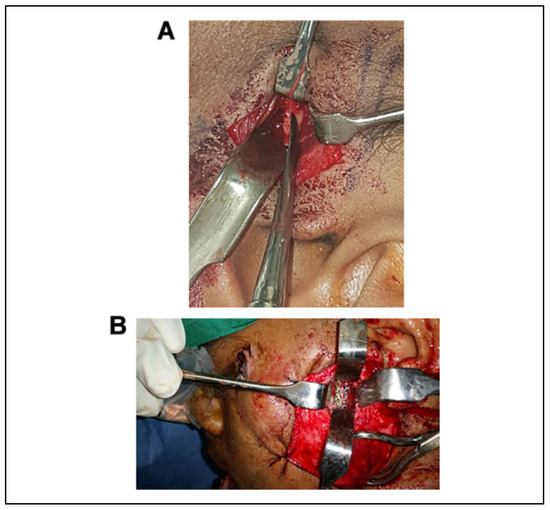

Figure 5.

A, Fracture prior to reduction. B, ORIF of condyle. ORIF indicates open reduction internal fixation.

Results

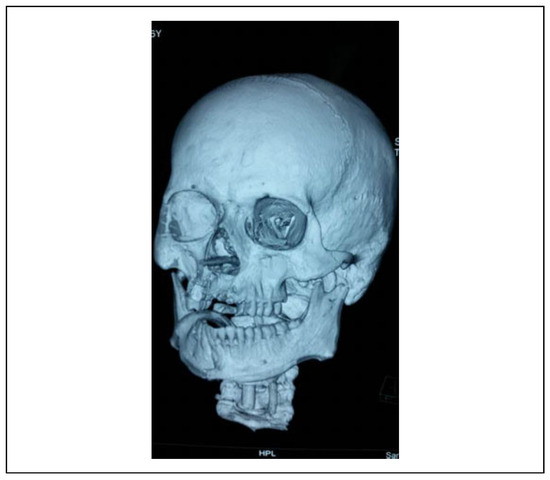

All patients were followed up for a minimum of 6 months to 1 year and postoperative results showed excellent occlusal relationships with no pain on full range of mandibular function. The mean degree of mouth opening was 4.0 cm. No mandibular deviations were noted in any patient during mouth opening. None of our patients had facial nerve weakness; they were fully assessed for all facial nerve functions postoperatively using the Yanagihara facial nerve grading system. None of our patients developed parotid salivary fistula/sailocele. Follow-up radiographs within the first postoperative day showed satisfactory anatomical reduction of the mandibular condyle fracture in all patients (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Postoperative CT. CT indicates computed tomography.

Discussion

Condyle fracture is a complex issue with multiple factors influencing the treatment decisions which include dislocation or degree of displacement, whether the fracture is unilateral or bilateral, presence of other mandibular fractures or facial fractures, inability to achieve occlusion, presence or absence of teeth, age of the patient.[1] Controversy over how to treat condyle fractures still exists. If occlusion is not disturbed, or only minimally disturbed, conservative treatment may simply involve a soft diet for several weeks and regular checkups or application of arch bars and elastic traction, especially in pediatric patients.[7,8] Decisions about whether to use open versus closed procedures depend on surgeon’s preferences and level of skill and experience,[4] as well as the location of the fracture site and the severity of displacement.[5] Generally, surgeons who prefer surgical treatment insist that only ORIF can prevent long-term effects such as shortening of the ramus, facial asymmetry, pain and arthrosis of the TMJ, and impairment of mastication and articular function; also, rehabilitation is achieved more quickly, so TMJ and mastication function will return to normal in a shorter period of time.[9]

Gu¨ven and Keskin presented 2 case reports of transcutaneous transparotid technique and emphasized that it is possible to reach the mandibular bone going through both the parotid tissue and the masseter muscle, avoiding injuries to branches of the facial nerve.[8] The authors suggested that this approach is most appropriate for placement of screws and stabilization of mandibular condyle fractures without facial nerve injury.[8] Croce et al.’s study of the transparotid approach for mandibular condylar fractures reported satisfactory results in 32 patients, without complications (eg, hematoma, bone resorption, or condylar necrosis), with no mastication difficulties and with preservation of the facial nerve in all cases.[10]

Shi et al. conducted a prospective study to introduce a new surgical approach for ORIF (using small titanium plates) of mandibular condyle fractures using a modified transparotid approach via the parotid mini-incision in 36 mandibular condyles, and surgical outcomes were evaluated.[11] Postoperative follow-up of patients ranged from 3 to 26 months. They found adequate mouth opening, occlusal relationships were excellent in all patients, and none had symptoms of intraoperative ipsilateral facial nerve injury. Study results showed that this procedure is safe and feasible for treating mandibular condyle fracture, and offers a short operative path, protection of the facial nerve, and satisfactory aesthetic outcomes.[11]

Our technique was similar to Shi et al.’s procedure where we reach the fracture going through both the parotid tissue and the masseter muscle, avoiding injuries to branches of the facial nerve; the fracture site is also directly exposed and if the facial nerve is found during dissection of the parotid tissue, it can be protected under direct vision, reducing the incidence of facial nerve injury (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Facial nerve.

A prospective study of postoperative facial nerve morbidity associated with ORIF of the fractured condyle found that only 7 (14%) out of 50 cases had temporary weakness of the facial nerve, affecting mostly the buccal and zygomatic branches. However, no permanent weakness was found in those cases, mean recovery to normal function was 4.2 months and occlusion was satisfactory in all except in 1 case. The authors concluded that ORIF is a safe procedure with acceptable morbidity.[10]

Surgical treatment of condylar fractures includes preauricular, submandibular, or retromandibular approaches. Preauricular incision is suitable for reduction of middle or high mandibular condyle fractures. Sufficient surgical exposure is difficult due to branch of facial nerve which limits the range of downward traction and joint capsule should also be cut open which may increase local injury.[5] Submandibular approach is used for middle or low TMJ fractures. The incision is distant from the fracture site causing traction of the periosteum and soft tissue limits access to the surgical field and distance increases the surgical difficulty and risk of surgical trauma.[5]

Retromandibular incision gives exposure to the posterior margin of the mandibular ramus. The surgical exposure and operation are relatively difficult for patients with a long mandibular ramus and higher mandibular condyle fractures, increasing risk of nerve and blood vessel injury.[12] A comparative study of complication rates associated with different incisions to access the TMJ fracture suggested that the retromandibular approaches provided a more direct visual field and nearly straight-line access for fracture fixation.[13] Other reports indicated that this approach does not effectively protect the facial nerve; the incidence of temporary postoperative facial nerve injury is as high as 38% to 40%, and permanent facial paralysis may occur in 1% of patients.[12,14]

Modified retro-mandibular approach resulted in only temporary facial nerve weakness in about 8% of patients.[15] Endoscope-assisted transoral treatment of displaced bilateral condylar mandible fractures has given satisfactory results. But it requires special equipment and special training.[14]

An in-depth comparative study between different surgical approaches for rigid fixation of subcondylar fracture of mandibles was conducted by Ebenezer and Ramalingam.[13] The study was conducted in 20 patients, who were categorized (5 each) into the preauricular, submandibular, retromandibular transparotid, or retromandibular transmasseteric group. Their mean time from incision to skin closure was 110 min in all 20 patients. Submandibular incision took the shortest time for approaching the fracture. Preauricular incision took longer time for suturing. They were able to see facial nerve branches in 14 of 20 cases, none of the nerves were injured permanently except for periorbital weakness in preauricular group in 3 patients, upper lip was involved in 3 cases (1 submandibular, 2 transparotid), and lower lip asymmetry was reported by 1 patient who underwent submandibular incision. Intraoperative bleeding was moderate. Two of the transparotid and 1 of the transmasseteric cases developed parotid fistulae which they treated conservatively by pressure dressing and antisialogogues. There were no cases of wound infection, Frey’s syndrome, pus discharge, abscess, or cellulitis in their procedures. The authors claim that the transmasseteric and transparotid approaches provided straight-line access and required lesser retraction. The transmasseteric approach is an approach that is easier to master and nerve damages can be avoided best.[13] Studies on transparotid approach showing advantages and complications is present in Table 1.

Table 1.

Transparotid Approach.

In our patients with condyle fracture, a small parotid incision directly over the fracture site provided the direct access needed for ORIF which allowed easy placement of the titanium plate. In addition, titanium screws can be placed perpendicular to the bone surface. Satisfactory postoperative healing was recorded (Figure 8). Minimal swelling was noted and postoperative pain management was with simple analgesics. The design of skin incision to expose the parotid capsule as explained earlier was in shape of “Lazy S.” Skin incision length/release depended on the facial type of patient, that is, thin face versus fat face. With the parotid capsule incision, the fracture site can be reached directly. No massive soft tissue dissection was needed. Periosteal dissection is limited; it provided sufficient blood supply to the fracture site during surgery. The facial nerve is safely placed within the parotid tissue. In 1 case, we visualized the nerve; it was successfully retracted and saved.

Figure 8.

Postoperative healing.

In our experience, there was no incidence of facial nerve injury with the transparotid approach compared with other approaches. The facial nerve injury is the most feared complication among surgeons. A precise knowledge of the distribution of the facial nerve and careful dissection during operation is the key for low incidence. Between the major branches of facial nerve, there is a space which is safe to use for approaching the condylar fracture. It is quite safe to use a knife to open the sheath of parotid gland. Blunt dissection through the parotid gland, as explained in technique using curved artery forceps, perpendicular to the long axis of the incision of parotid sheath was found very safe. Cautery is never advised. Facial nerve lies on the interface between the superficial and deep parotid gland. Goal is to dissect through the nerve-sparing space between the major branches, usually between the zygomatic and buccal branches or the buccal and marginal mandibular branches. If a major branch is seen during dissection, it’s better to just retract it away or protect it by changing the direction of dissection away. Once in masseter muscle, a cautery was used and fractures were exposed. The second complication of parotid fistula was avoided by getting a watertight closure of the parotid fascia and occlusive dressing. This technique was simple even in hand of inexperience surgeons if they follow the set protocols.

Transverse or oblique incision in the parotid fascia was made just to expose the parotid tissue; care was taken not to deepen the incision. Thereafter, only blunt dissection was carried out. The fracture site was palpated, to guide our dissection. No bleeding was noted in this region. Mild bleeding was noted as we reached the masseter. Fractures were reduced and fixed.

Mild complications like swelling, pain, and mild malocclusion were noted which were managed accordingly. No major complications like facial nerve injury, sailocele, infection, bleeding, and Frey’s syndrome were recorded.

Conclusion

Our technique is technically simple for minimally experienced surgeon. It’s a simple technique to master. Complications if done correctly are almost nil. Scar is acceptable by the patient. Any type of condyle fracture can be managed by this technique without difficulty.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Villareal, P.M.; Monje, F.; Junquera, L.M.; Mateo, J.; Morrillo, A.J.; Gonza’lez, C. Mandibular condyle fractures: Determinants of treatment and outcome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004, 62, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacchariades, N.; Papavassiliou, D. The pattern and aetiology of maxillofacial injuries in Greece. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1990, 18, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, S.L. A new operation for displaced fractures at the neck of the mandibular condyle. Dental Cosmos. 1925, 67, 876–877. [Google Scholar]

- Güerrissi, J.O. A transparotid transcutaneous approach for internal rigid fixation in condylar fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2002, 13, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.Y.; Yang, J.D.; Chung, H.Y.; Cho, B.C. Current concepts in the mandibular condyle fracture management part II: Open reduction versus closed reduction. Arch Plast Surg. 2012, 39, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Downie, J.J.; Devlin, M.E.; Carton, A.T.; Hislop, W.S. Prospective study of morbidity associated with open reduction and internal fixation of the fractured condyle by the transparotid approach. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009, 47, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strobl, H.; Elmshoff, R.; Rothler, G. Conservative treatment of unilateral condylar fractures in children: A long-term clinical and radiologic follow-up of 55 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999, 28, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güven, O.; Keskin, A. Remodeling following condylar fractures in children. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2001, 29, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Devlin, M.F.; Hislop, W.S.; Carton, A.T.M. Open reduction and internal fixation of fractured mandibular condyles by a retromandibular approach: Surgical morbidity and informed consent. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002, 40, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croce, A.; Moretti, A.; Vitullo, F.; Castriotta, A.; DeRosa, M.; Citrarol, L. Transparotid approach for mandibular condylar neck and subcondylar fractures. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2010, 30, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Yuan, H.; Xu, B. Treatment of mandibular condyle fractures using a modified transparotid approach via the parotid mini-incision: Experience with 31 cases. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83525. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, E.; Dean, J. Rigid fixation of mandibular condyle fractures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993, 76, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ebenezer, V.; Ramalingam, B. Comparison of approaches for the rigid fixation of sub-condylar fractures. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2011, 10, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manisali, M.; Amin, M.; Aghabeigi, B.; Newman, L. Retromandibular approach to the mandibular condyle: A clinical and cadaveric study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003, 32, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schoen, R.; Fakler, O.; Metzger, M.C.; Weyer, N.; Schmelzeisen, R. Preliminary functional results of endoscope-assisted transoral treatment of displaced bilateral condylar mandible fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008, 37, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shi, D.; Patil, P.M.; Gupta, R. Facial nerve injuries associated with the retromandibular transparotid approach for reduction and fixation of mandibular condyle fractures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015, 43, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutia, O.; Kumar, L.; Jose, A.; Roychoudhury, A.; Trikha, A. Evaluation of facial nerve following open reduction and internal fixation of subcondylar fracture through retromandibular transparotid approach. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014, 52, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2020 by the author. The Author(s) 2020.