Introduction

Mandibular fractures account for 36% to 70% of all facial fractures, one of the most frequently encountered sequela of traumas involving the maxillofacial region.[

1,

2] Of all facial fractures treated with reduction, they have the highest incidence and prevalence and are most commonly caused by physical assault, motor vehicle collisions (MVCs), falls, alcohol, and drugs.[

3,

4] Treatment options include either closed reduction (CR) or open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF). The paradigms of management for mandibular fractures have been in flux for the past 20 years and treatment algorithms continue to be controversial.[

5,

6] Factors that drive treatment decisions include the complexity of the fracture, height of the fracture, patient age, degree of occlusion dysfunction, and dentition.[

7] The case-specific complexities involved in facial fracture management have made it difficult to establish universal treatment guidelines; surgeon judgment and preference significantly contribute to management decisions.

Subjectivity in clinical decision-making may lead to biases that result in disparate care, and health-care disparities related to socioeconomic status are well described in the literature. While blatant explicit bias is not prevalent, a substantial body of evidence demonstrates that clinical decision-making is often affected by race and socioeconomic status.[

8,

9,

10] These factors have been shown to impact the management and outcomes of a diverse array of disease processes including abdominal aortic aneurysms,[

9] hepatocellular carcinoma,[

10] pancreatic cancer,[

11] esophageal cancer,[

12] and ventral hernias. For instance, non-white patients undergo open versus laparoscopic repair of incisional hernias at a significantly higher rate than the white population.[

13] Of all surgical specialties, health-care disparities have been most widely studied in the trauma population. Previous studies have shown that socioeconomic status impacts mortality as well as the ability to access posthospitalization care in trauma patients.[

14,

15]

In patients admitted for unilateral condylar mandibular fractures, it has been shown that there are significant differences between the populations receiving CR versus ORIF based on race, income, insurance status, and hospital type (ie, academic, rural, etc); and those patients undergoing ORIF incurred longer hospital stays, more cost, and increased bleeding complications.[

16] To our knowledge, no study has assessed the effect of patient race and insurance status on clinical decision-making in any simple mandibular fracture repair. Thus, the objective of this project was to assess the impact of these factors in whether patients underwent closed or open reduction of all simple mandibular fractures. We hypothesized that socioeconomically disadvantaged patients (ie, non-white, uninsured) would be more likely to undergo ORIF than CR and assume any potential associated burdens.

Results

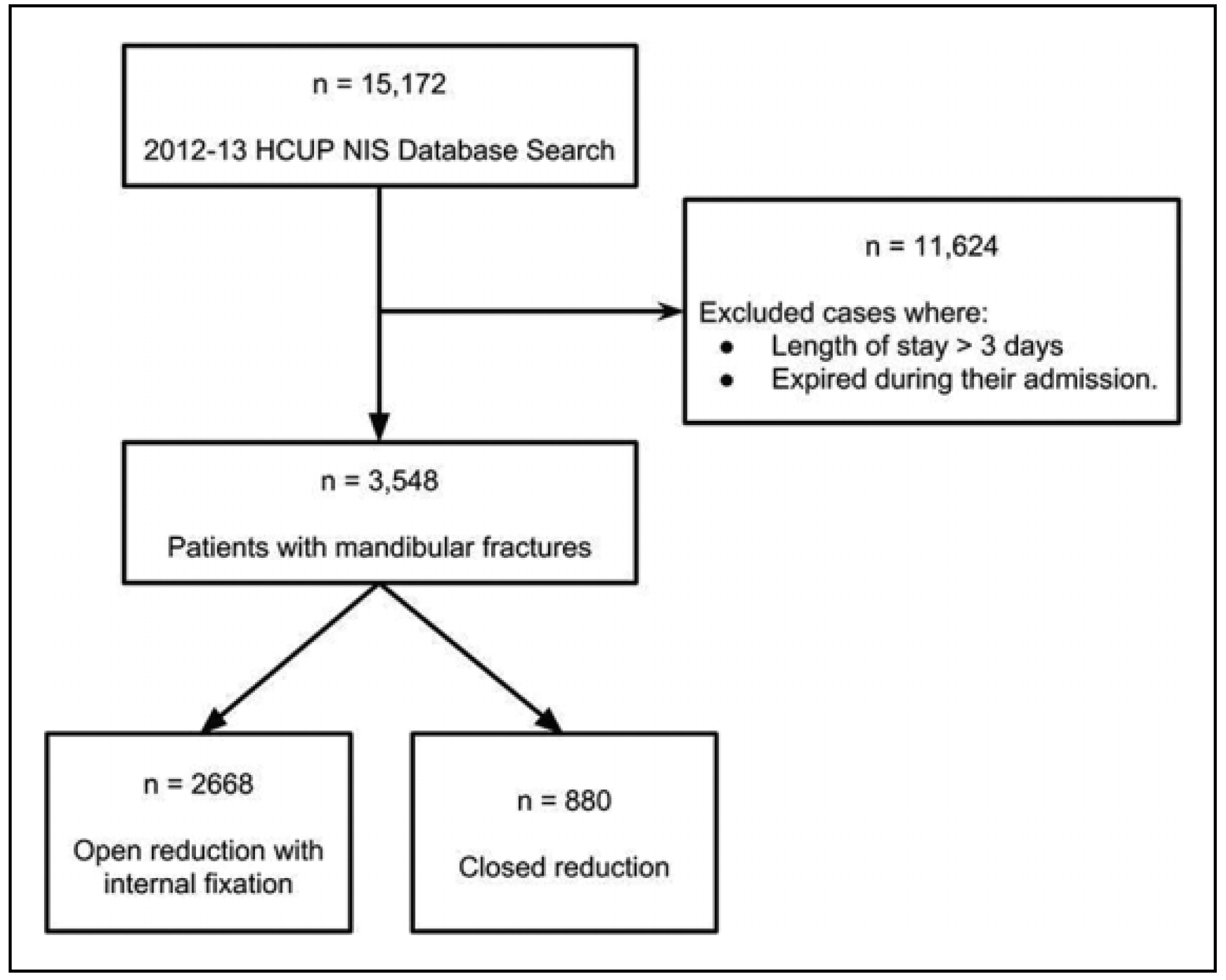

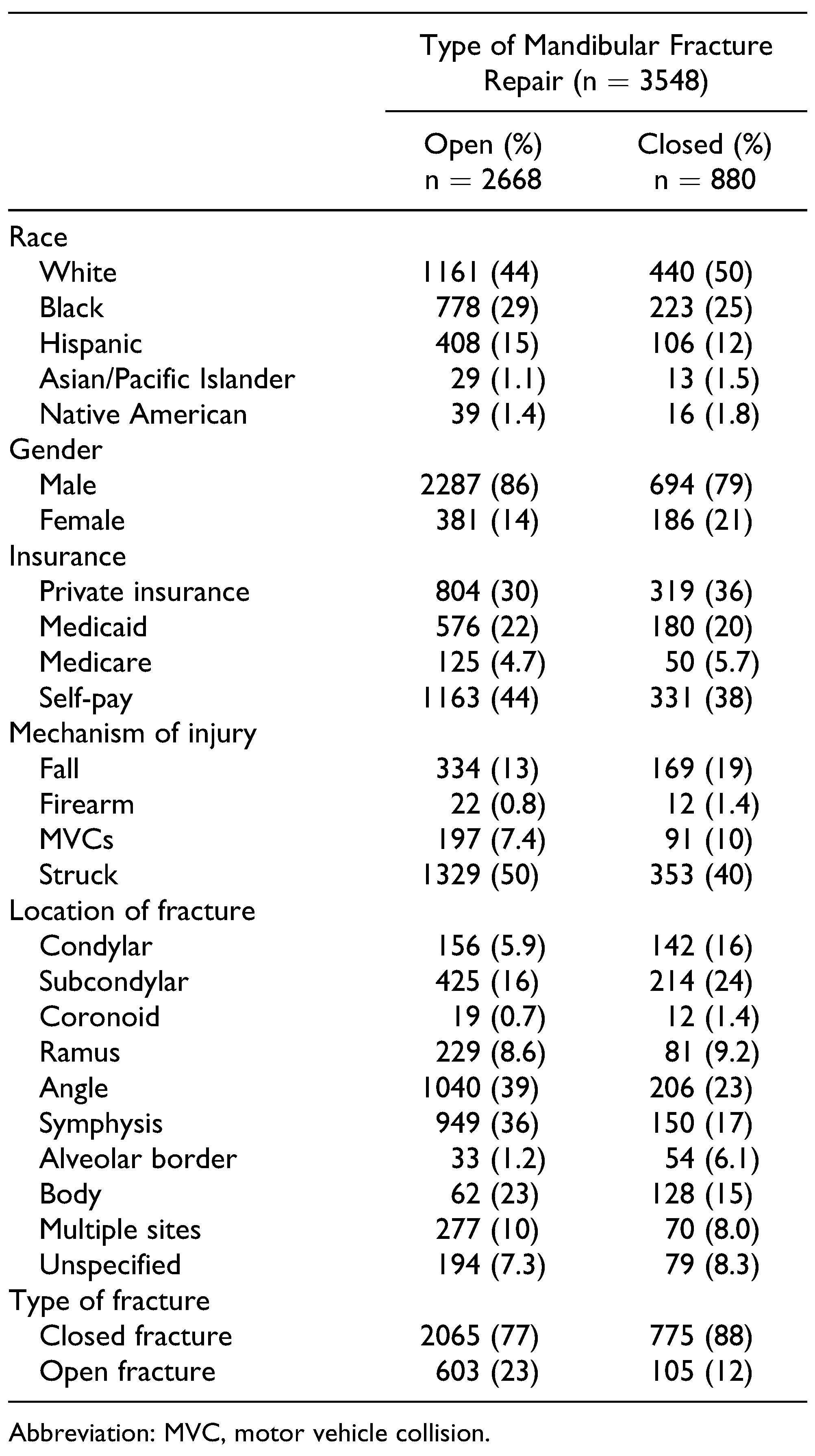

A total of 3548 patients with simple mandibular fractures that met inclusion criteria were identified, with 2668 patients undergoing ORIF and 880 patients undergoing CR (

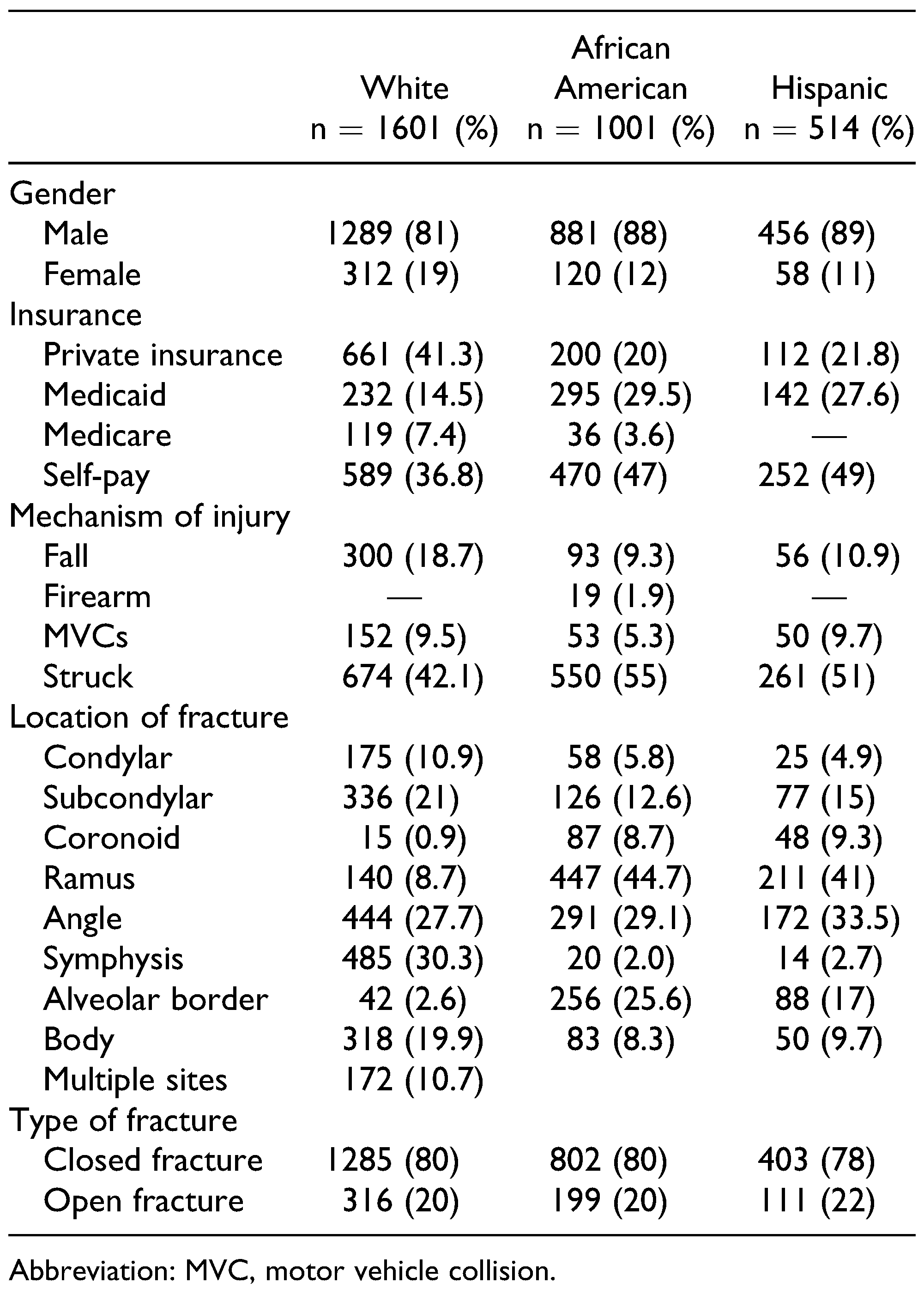

Figure 1). Patient gender, insurance status, mechanism of injury, and anatomic location of fracture are delineated by race and described in

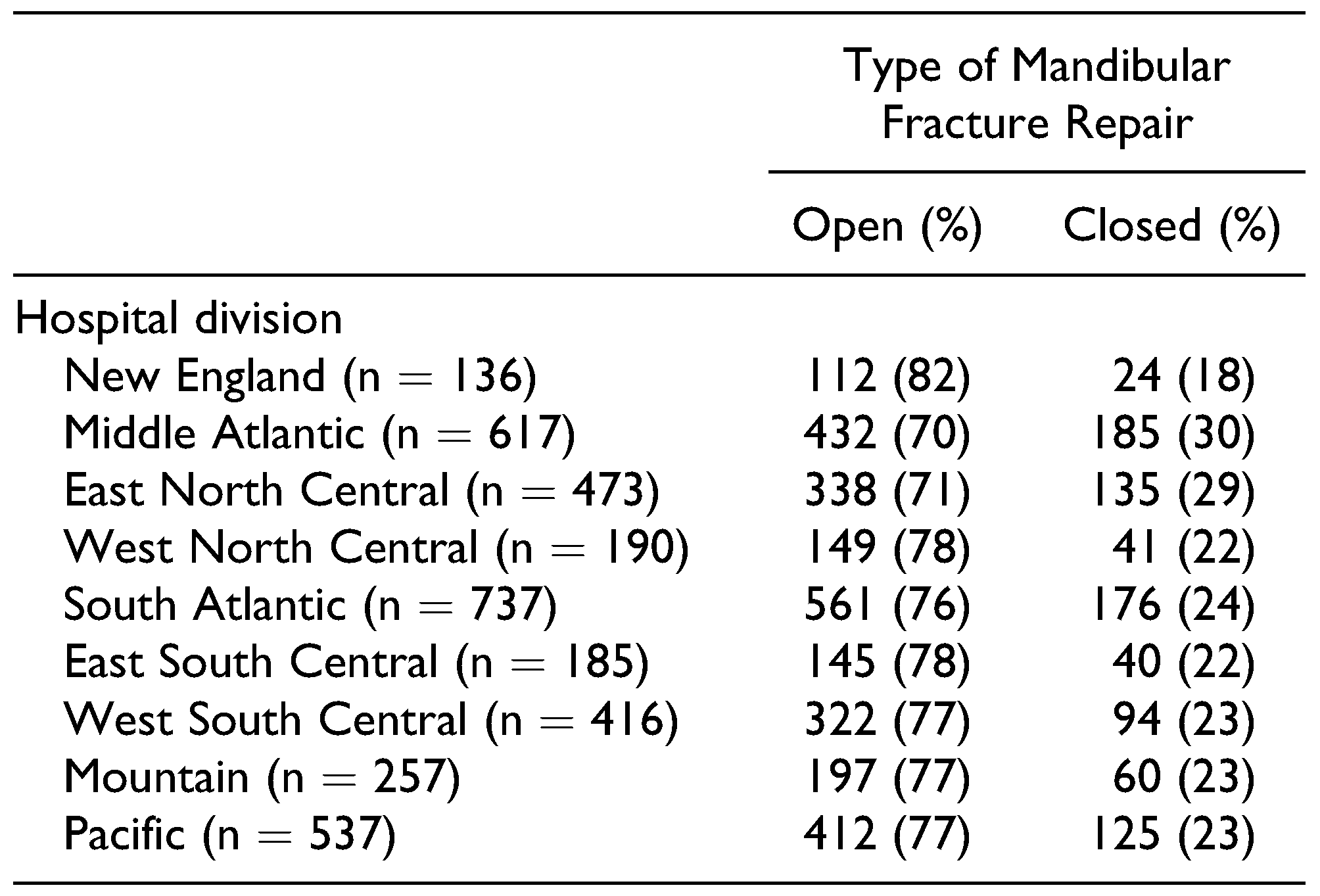

Table 2. The rates of open reduction and CR stratified by hospital regions are described in

Table 3. The frequency of open reduction and CR based on patient race, gender, insurance status, mechanism of fracture, and fracture location are listed in

Table 4.

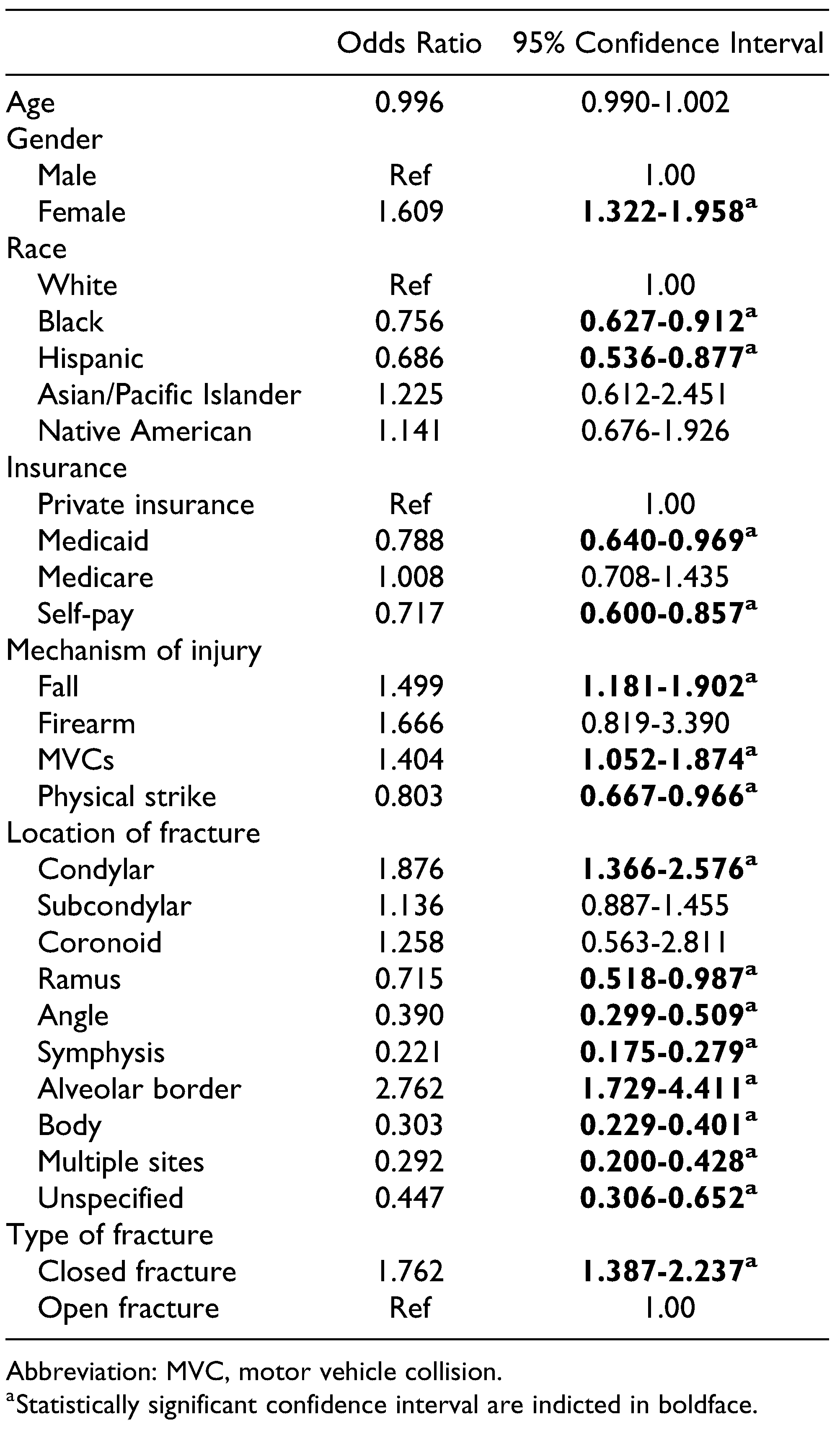

Factors associated with CR (versus ORIF) on univariate analysis were female gender (OR 1.609, 95% CI 1.322-1.958), fall mechanism (OR 1.499, 95% CI 1.181-1.902), MVC mechanism (OR 1.404, 95% CI 1.052-1.874), condylar fractures (OR 1.876, 95% CI 1.366-2.576), and alveolar border fractures (OR 2.762, 95% CI 1.729-4.411) (

Table 5). The following factors were associated with ORIF (versus CR): black (OR 0.756, 95% CI 0.627-0.912), Hispanic (OR 0.686, 95% CI 0.536-0.877), self-pay insurance status (OR 0.717, 95% CI 0.600-0.857), physical strike mechanism (OR 0.803, 95% CI 0.667-0.966), ramus fractures (OR 0.715, 95% CI 0.518-0.987), angle fractures (OR 0.390, 95% CI 0.299-0.509), symphysis fractures (OR 0.221, 95% CI 0.175-0.279), body fractures (OR 0.303, 95% CI 0.229-0.401), and multiple fractures (OR 0.292, 95% CI 0.200-0.428).

Independent factors associated with CR (versus ORIF) on multivariate analysis were female gender (OR 1.304, 95% CI 1.040-1.634), firearm mechanism (OR 2.468, 95% CI 1.120-5.437), condylar fractures (OR 1.811, 95% CI 1.308-2.508), alveolar border fractures (OR 2.669, 95% CI 1.623-4.389), and closed fractures (OR 1.892, 95% CI 1.468-2.439) (

Table 6). The following factors were independently associated with ORIF (versus CR) using multivariate analysis: rami fractures (OR 0.705, 95% CI 0.504-0.985), angle fractures (OR 0.399, 95% CI 0.306-0.521), body fractures (OR 0.301, 95% CI 0.227-0.400), and multiple fractures (OR 0.272, 95% CI 0.185-0.400). Race and insurance status were no longer statistically significant variables on multivariate analysis.

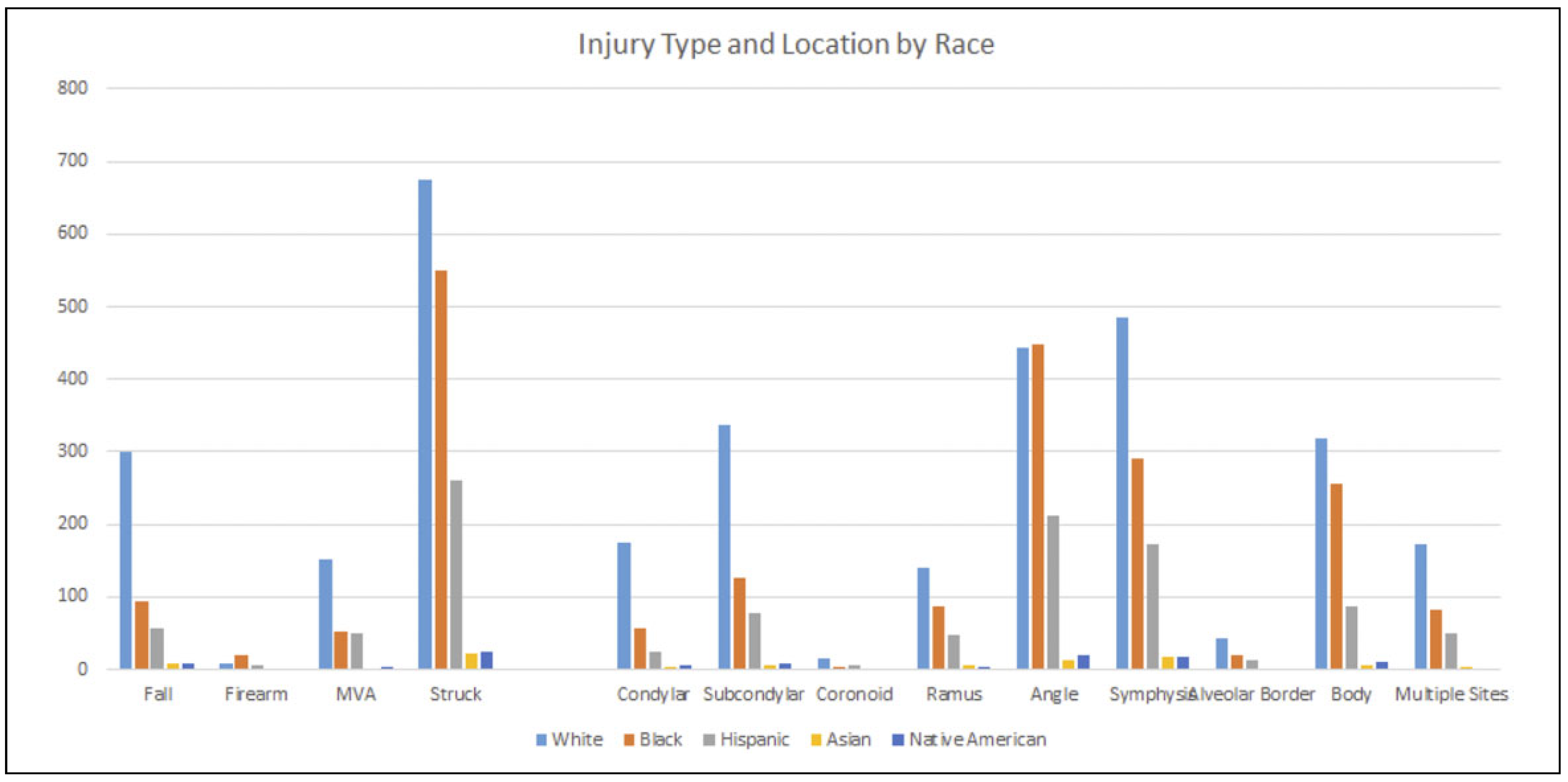

To further elucidate whether race and insurance status were associated with fracture location and mechanism of injury, the frequencies of injuries and anatomic fracture location within racial subsets were calculated. Interestingly, black and Hispanic patients have a higher likelihood of being physically assaulted (55% and 51%, respectively) compared to white patients (42%), and a higher likelihood of angular fractures (45% and 41%, respectively) compared to white patients (27%) (

Figure 2).

When compared to the Middle Atlantic region, using multivariate analysis, patients treated in all other regions were more likely to receive ORIF than CR (New England OR 0.475, 95% CI 0.273-0.828; West North Central OR 0.548, 95% CI 0.333-0.902; South Atlantic OR 0.599, 95% CI 0.438-0.820; East South Central OR 0.585, 95% CI 0.383-0.893; West South Central OR 0.658, 95% CI 0.447-0.970; Mountain OR 0.569, 95% CI 0.367-0.881; Pacific OR 0.639, 95% CI 0.453-0.901) (

Table 7). There were no statistically significant differences in the likelihood of undergoing either CR or open reduction in the East North Central region relative to the Middle Atlantic region (OR 1.003, 95% CI 0.720-1.398).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the impact that race and insurance status (factors contributing to socioeconomic status) have in whether patients underwent CR or ORIF of their simple mandibular fractures. We hypothesized that race and insurance status would affect the clinical management of these fractures; socioeconomically disadvantaged patients would disproportionately receive an open repair— and the health and financial implications associated with it.[

16] While health-care management and outcomes disparities are well-established in trauma literature, its impact on simple factures of the mandible has not been well described.

Our study is consistent with previous studies in terms of mandibular fracture demographics. Males made up the majority of patients with mandibular fractures.[

3] Furthermore, compared to the US Census statistics, African Americans made up a disproportionately high percentage of mandibular fractures (28.2%).[

3,

18,

19] Many studies have shown physical assault, falls, and MVCs to be the most frequent mechanisms of injury.[

18,

20,

21] Our findings were similar, with assault, fall, and MVC as the most common injury mechanisms (

Table 4).

Using univariate analysis, race and insurance status seemed to significantly affect the decision between patients undergoing ORIF versus CR, as African Americans, Hispanics, and self-pay patients were more likely to receive ORIF (

Table 5). This would have suggested that patients who are non-white, uninsured, or receiving federal health coverage (ie Medicaid) are more likely to undergo open reduction for their simple mandibular fractures than their white, privately insured counterparts. However, when all covariates were adjusted for on multivariate regression, race and insurance status did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in the likelihood of undergoing ORIF versus CR. This would suggest that simple mandibular fracture treatment could be a subset of trauma management where patient race and insurance status may not have as significant an influence as demonstrated elsewhere.

Patients with a firearm injury were more likely to undergo CR using both univariate and multivariate analyses (

Table 6). This is seemingly counterintuitive. However, our exclusion criteria, designed to eliminate polytrauma patients, likely skewed these data toward less severe mandibular fractures, thus allowing for management with CR. Rana et al demonstrated that since the advent of rigid fixation, open reduction appears to be the superior and more popular approach for mandibular fracture treatment after firearm injury.[

22] Our results would have likely demonstrated similar findings if we had not excluded patients with a hospital length greater than 3 days or who expired during their admission. High velocity firearm injuries frequently result in other associated injuries and also generally require ORIF to properly manage the fracture; thus, by imposing our exclusion criteria, we likely did not capture this subset of the population.

When analyzing anatomic fracture location in a univariate fashion, angle, symphysis, and body fractures were more likely to undergo ORIF while condylar and alveolar border fractures were more likely to undergo CR (

Table 6). These relationships were further validated as independent associations on multivariate analysis (

Table 7). Our results support that of previous studies and clinical practice patterns: condylar fractures are typically treated with CR.[

23] Furthermore, our results also support the generally accepted clinical practice of treating alveolar border fractures with CR (

Table 6 and

Table 7).

Using univariate analysis, physical assault is one of the only mechanisms of injury, and angular fractures the only anatomic location, that are more likely to undergo ORIF (

Table 5). Including the aforementioned race and insurance data, it would imply that black and Hispanic, or uninsured patients are more likely to be injured with a physical strike, leading to a higher prevalence of angular fractures—thus leading to a higher likelihood of ORIF. However, on multivariate analysis, angular fractures are independently associated with ORIF, whereas race and insurance status are not. Therefore, the greatest contributing factor in management decision-making between CR and ORIF is the anatomic location of the fracture, with no significant contribution from patient race or insurance status.

Regional differences also exist in management choice for simple mandibular fractures. Patients were more likely to receive ORIF in all regions when compared to the Middle Atlantic region. We suspect, given how surgeonspecific the management strategy of mandibular fractures can be, that differences seen in the likelihood of CR versus ORIF are dictated by surgeon training pedigree. These surgeons are often trained at high-volume, academic centers whose catchment area can encompass several states. Once graduated, these surgeons start their practice and propagate training patterns throughout a region. However, regional differences were not thoroughly explored in this study. Future geographic studies are needed to evaluate the reasons behind these regional differences.

It is not a novel concept that factors outside of the clinical realm affect clinical outcomes. As previously mentioned, this has been extensively studied in the classically disadvantaged trauma population. Greene et al used the National Trauma Database to look at penetrating versus blunt injuries; the study found that uninsured patients had an increased risk of death versus insured patients in both penetrating and blunt injury.[

14] Englum et al demonstrated that uninsured patients had shorter lengths of stay compared to insured patients.[

15] The study reasoned that it was possibly due to uninsured patients having a lower payment ability and being discharged sooner—perhaps sooner than indicated. Hicks et al demonstrated that younger, African American trauma patients had a greater likelihood of death compared to white patients.[

24] However, neither race nor insurance status are significantly associated with ORIF versus CR in simple fractures of the mandible.

One of the major limitations of this study is the lack of granularity found in large, retrospective studies. These data are only from the 2012 and 2013 NIS due to institutional availability. Mandibular fracture management is a dynamic topic and we were unable to evaluate whether these trends hold true over a longer time period. Future studies can be performed to evaluate these trends. In addition, the study was designed to attempt exclusion of polytrauma patients and patients with an extended hospital course, so that only simple mandibular fractures comprised the study cohort. However, by doing so, our data focus on less severe trauma, possibly affecting the ratio of open reduction versus CR. Therefore, our data only generalize to patients well enough to leave the hospital in 3 days.

The primary strength of this study was the large, nationally representative, and diverse population. NIS represents a 20% sample of all inpatients discharged from US hospitals and is an accurate representation of the US population, allowing for significant generalizability.