Introduction

The treatment of mandibular condyle fractures remains a controversial topic in maxillofacial (MF) surgery. Despite being one of the more frequent facial fractures, there is still ongoing debate between open and closed treatment modalities. Even for the different methods of conservative management, a uniform treatment protocol is lacking.[

1]

The mandible is involved in 18-66% of facial fractures.[

1,

2] An analysis of the frequency of mandible fracture sites showed that condylar fractures occur in 25-40% of cases.[

3,

4] In a review of cases by Fridrich et al, condylar fractures were the second most prevalent mandibular fracture after mandibular angle fractures.[

5] Bilateral fractures are present in 24-41% of cases.[

2,

6]

Complications concerning trauma affecting the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) are far reaching in their effects and may not always be immediately visible. Such complications can include disrupted occlusal function, deviation of the mandible, internal derangement of the TMJ, facial asymmetry, nerve injury, intra-articular and extra-articular ankyloses, and limited jaw movement.[

7] Historically, conservative management with or without maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) is the preferred choice of treatment. However, due to advances in medical technology and improvements in the field of osteosynthesis, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) have become widely accepted.[

8] The choice between these two treatment modalities remains highly controversial. Various elements, such as patient age, fracture level, angulation of fragments, patient systemic status, other fractures, the presence (or absence) of teeth, the possibility of occlusal restoration by MMF, the presence of foreign materials, and practice management issues, determine treatment choice.[

1,

2,

9]

This article aims to contribute to this discussion by adding a retrospective single-center cohort of patients with condylar fractures and their treatment, followed by a short review of the literature.

Patients and Methods

This study was evaluated and approved by the KU Leuven and UZ Leuven ethics committee (number mp14689). All available data were gathered on patients presenting at Leuven University Hospitals, Belgium, with MF trauma between January 2009 and December 2015 (6-year duration) by performing a search through the OMFS database of UZ Leuven using the following terms: trauma, fracture, contusion in combination with caput, condyle, subcondylar, condylar head, joint, ascending ramus, and intracondylar. Clinical, surgical, and radiological notes were systematically searched to evaluate the epidemiological and etiological factors of condylar trauma in a largely urban population. The collected data included gender, age, cause of trauma, diagnosis, level of fracture, dislocation of the fracture, occlusion, associated fractures, nerve injury, dental status, shortening of the mandibular ramus height, treatment methods, complaints about TMJ function after treatment, and duration of follow-up. Exclusion criteria were mandibular fractures without the presence of condylar fracture and pathological fractures. Patients who received their initial treatment elsewhere but consulted at UZ Leuven for a second opinion with good documentation of their initial treatment were included in study.

In all cases, diagnosis was established using panoramic radiographs, cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), and multislice CT. Fractures were divided into condylar head, neck, or subcondylar fractures.[

2,

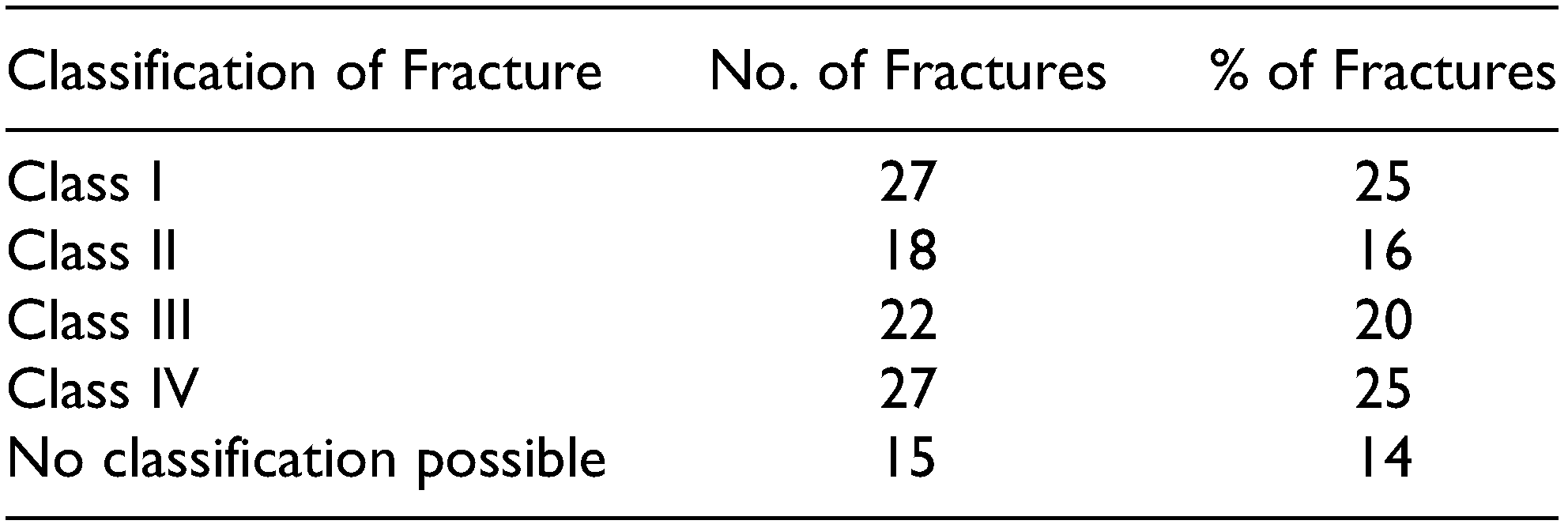

10] Classification according to MacLennan[

11] was used to determine the level of displacement using four classes: (I) non-displaced, (II) deviation at the fracture line (no full loss of contact between fragments), (III) displacement (condylar fragment not in contact with the distal fragment but condyle still in the glenoid fossa), and (IV) dislocation (condyle dislocated from the glenoid fossa). If available, CT or CBCT was used to determine displacement and angulation.

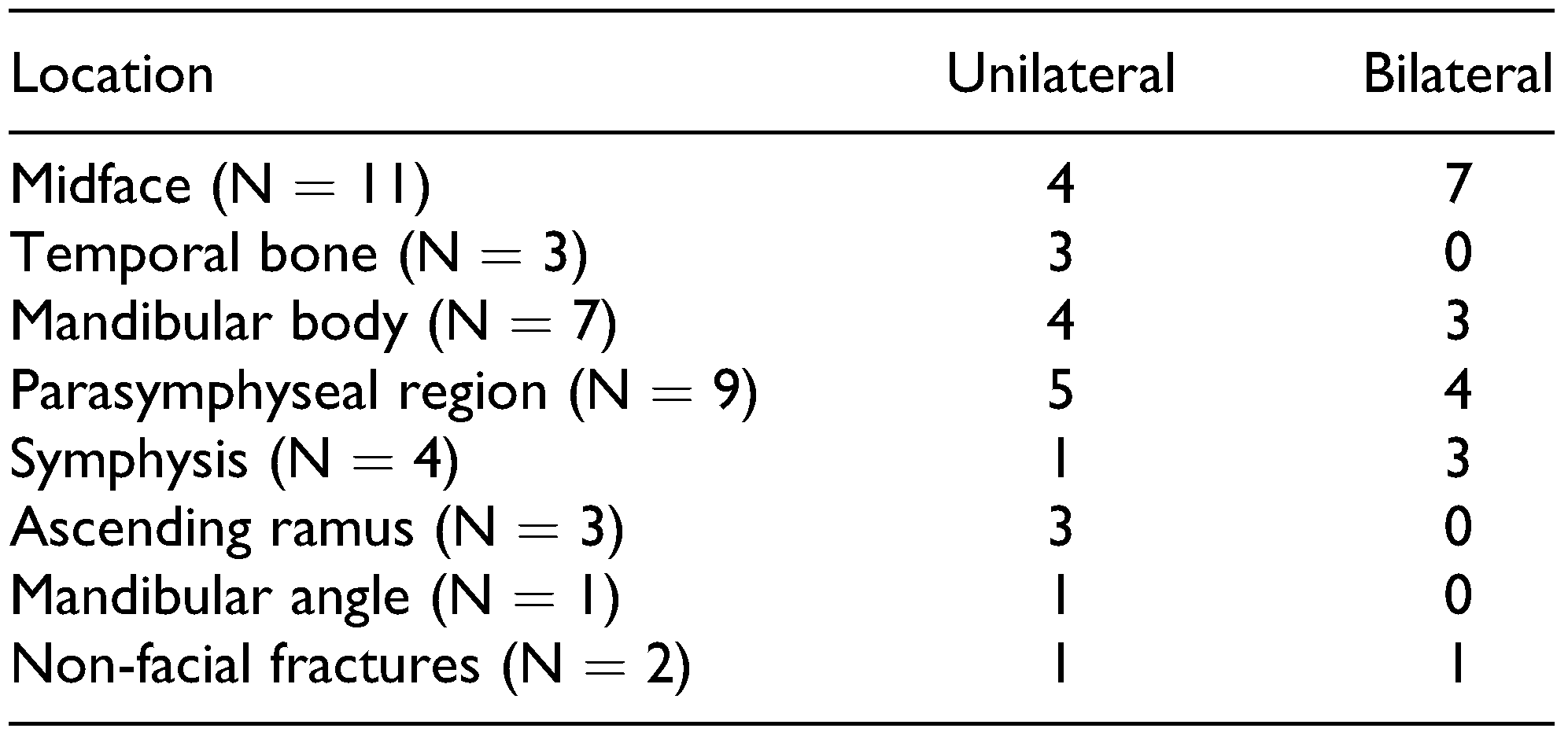

Condylar fractures were grouped as unilateral or bilateral fractures. Associated MF fractures were classified according to their location: symphyseal, parasymphyseal, or dentoalveolar. Fractures of the midfacial area included different zygoma, orbital floor, Le Fort 1, and sinus wall fractures. Other fractures were classified according to the anatomic site if data were available.

Patients were divided according to age, paying special attention to children (patients up to 18 years old), as treatment of this group has to take into account the different physiological healing capacities of the growing joint.[

8,

12] Treatment was either surgical (ORIF) or non-surgical (including MMF, physiotherapy, and conservative treatment with soft and fluid alimentation).

An evaluation by telephone was performed after an average 261 weeks in the conservative group and 304 weeks in the surgical in order to obtain a long-term patient-reported outcome. We asked whether they experienced limited mouth opening, a change in occlusion, facial asymmetry, nerve injury, TMJ complaints, external aftercare, or surgery. We then classified the fractures according to the treatment protocol of Mathes[

9] in order to determine the effect of conservative treatment in a population indicated for surgical intervention according to this treatment protocol.

This treatment protocol[

9] lists five absolute criteria for ORIF: malocclusion in CR, angulation between fragments >30

◦, distance between fragments > 5 mm, lateral override between fragments, and lack of contact between the fracture fragments. We compared fractures abiding by these absolute criteria for surgical treatment but were treated conservatively and fractures indicated for conservative treatment that were treated conservatively. Each criterion was evaluated in both the short- and the long-term outcome, except malocclusion in CR, which could not be evaluated due to incomplete pre-surgical notes.

Results

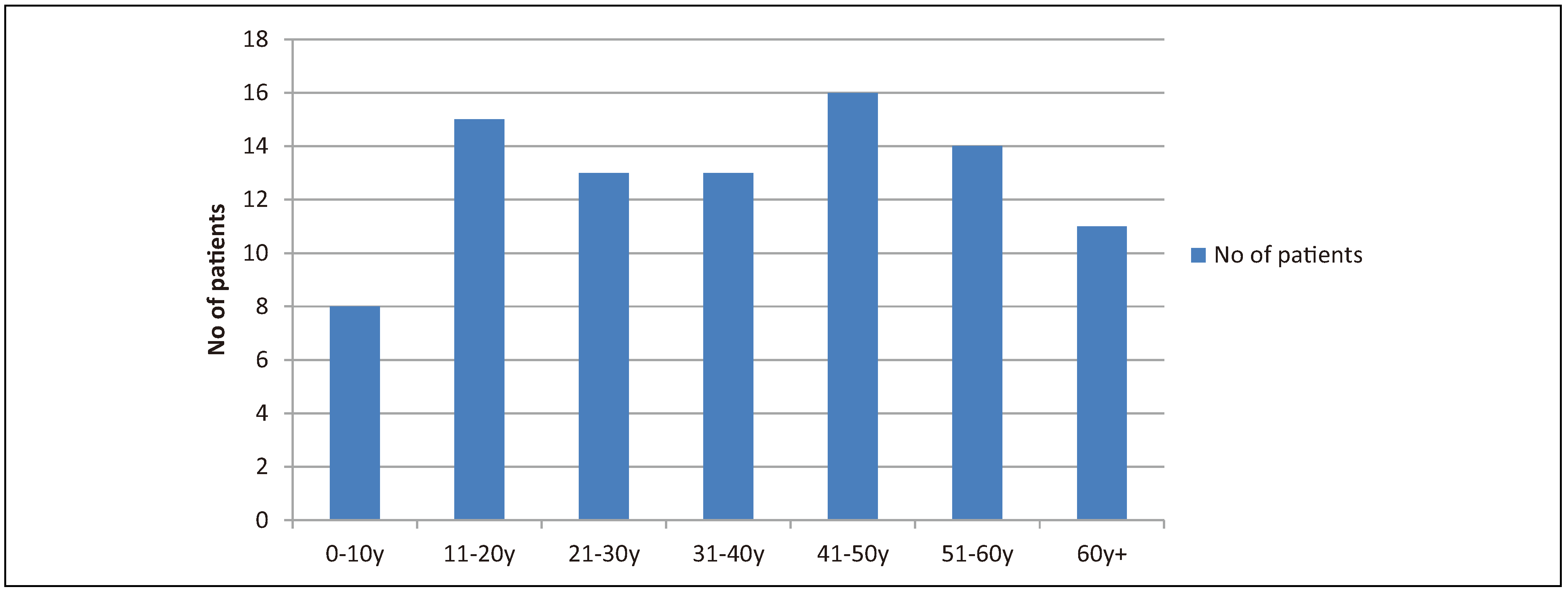

The initial data set consisted of 314 unique patients in whose notes trauma or the TMJ was mentioned. Ninety of these patients presented with a condylar fracture (

Table 1). The male/female ratio was approximately 1.14:1 (48 males and 42 females). The average age of presentation with a condylar fracture was 38 years. Patient age varied between 4 and 81 years (

Figure 1).

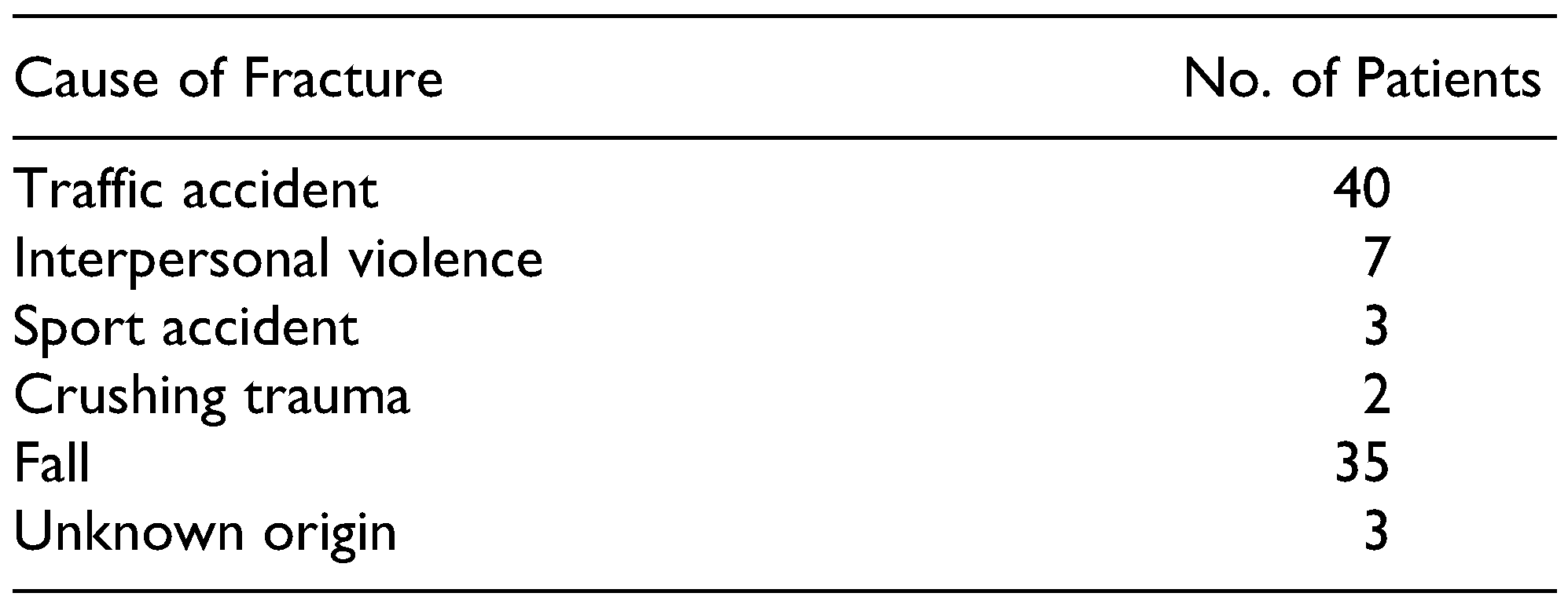

Traffic accidents were the most common cause of trauma, including 32 cases with recreational cyclists (

Table 2). The distribution of fracture type and location is given in

Table 3. Associated fractures were present in 32 cases (36%;

Table 4). Bilateral fractures were associated with other fractures in 11 cases (57% of bilateral fractures). Unilateral fractures were associated with other fractures in 21 cases (25% of unilateral fractures). Seven parade ground or guardsmen fractures were observed; these were bilateral condylar fractures in combination with a (para)-symphyseal fracture.[

13]

Of the 90 cases, 84 (93%) were treated conservatively (functional therapy with or without MMF). Six patients (7%) were treated with ORIF. All patients were given extensive informed consent concerning the possible complications of open surgery, such as facial nerve injury and formation of scar tissue. This led most patients to opt for conservative treatment. Being a very small sample, the open treatment group will not be discussed any further.

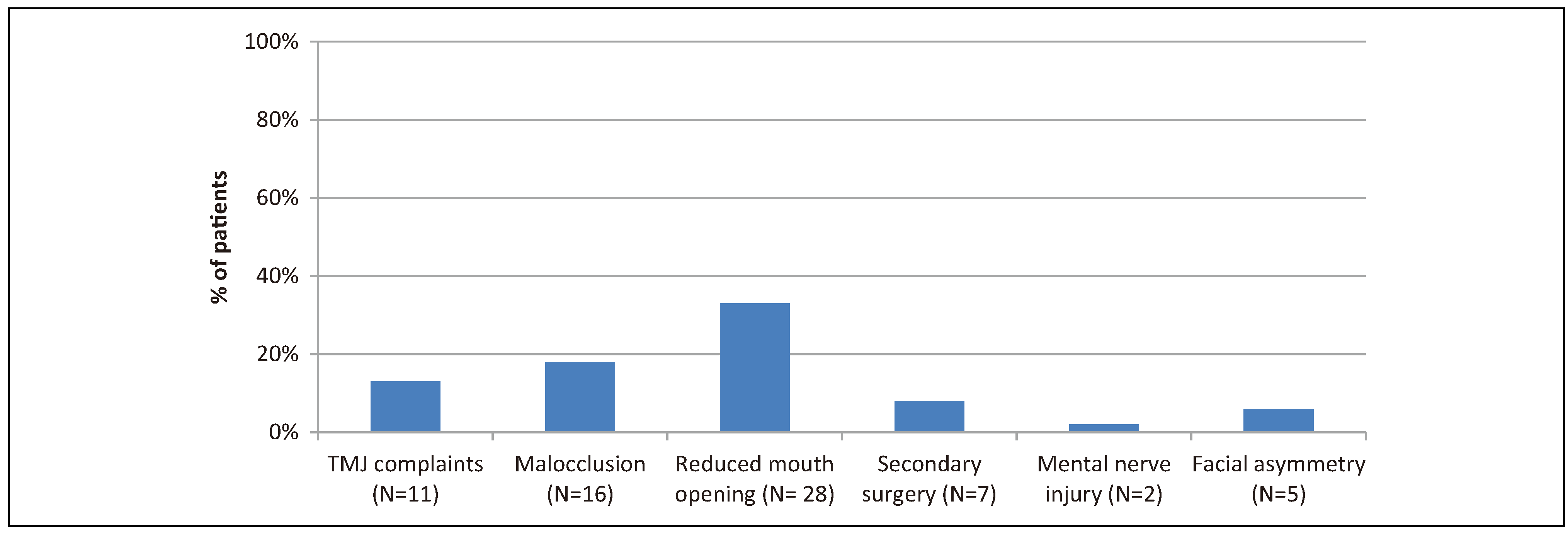

The average duration of follow-up in the conservative group was 13 weeks (

Figure 2). The duration of follow-up varied between 3 weeks and 2 years (median follow-up: 8 weeks). Loss to follow-up occurred mostly with patients with limited to no symptoms, as they did not feel that any further follow-up was needed. MMF was used in 43 cases (47%). Forty-one cases (46%) were treated conservatively without MMF. At the end of follow-up (13 weeks), the average mouth opening was 56 mm. The final mouth opening was not documented in 19 patients. Protrusion and laterotrusion were sparsely examined and not included as parameters for normal joint mobility.

The most frequent complication was a reduced mouth opening. Twenty-eight patients (33%) had an interincisal mouth opening <40 mm after an average of 13 weeks. The second most frequent complication was a persistent non-pre-existent malocclusion (n = 16 patients, 18%). TMJ complaints persisted in 11 patients (13%). Seven patients (8%) required secondary surgery due to various other complications. In two patients, a mental nerve injury persisted. However, these were most likely not caused by the condylar fracture but by an associated (para)symphyseal fracture or deep laceration. No other nerve injury was reported. Facial asymmetry was observed in five patients.

TMJ complaints were analyzed further. Clicking was present in 4 cases (5%). Locking and crepitation were observed in 2 patients (2%). Pain, ankylosis, disc dislocation, and condylar resorption (unilateral) were observed in only 1 patient (1%).

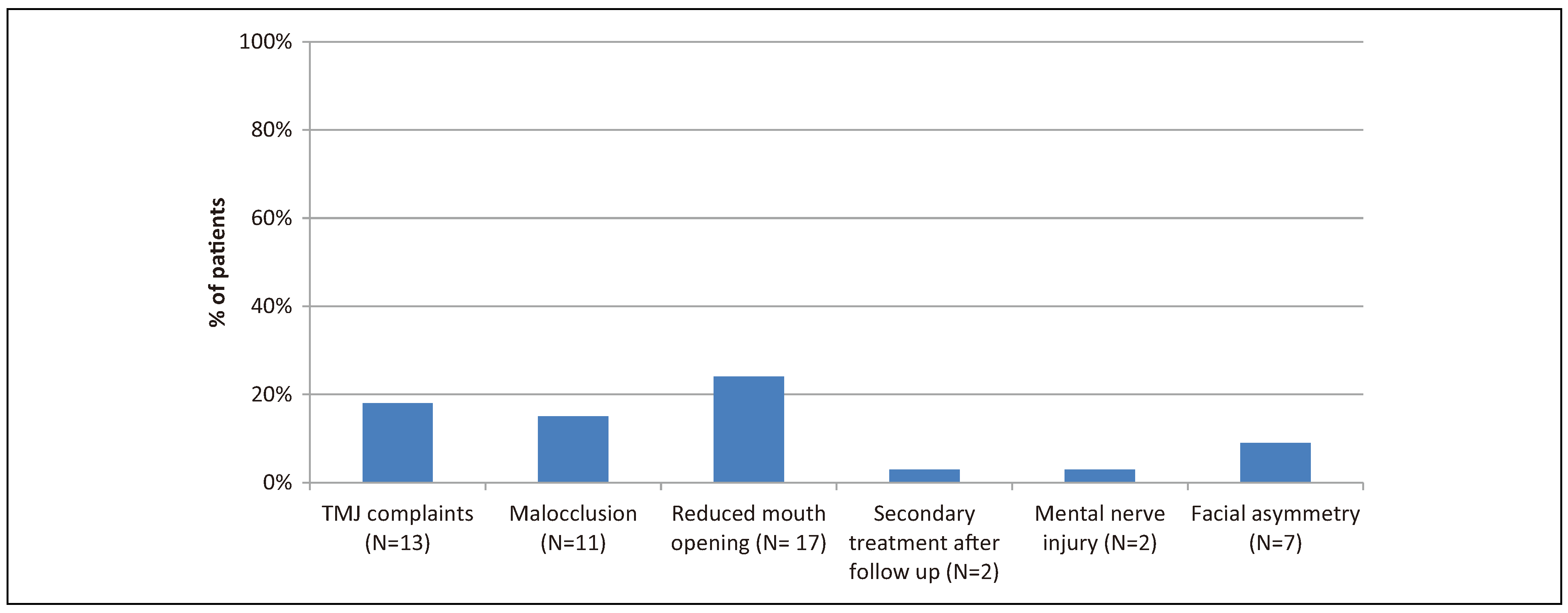

Patient-reported outcomes were obtained for the conservative group after an average of 261 weeks, with the interval between trauma and phone call ranging from 100 and 420 weeks (

Figure 3). Outcomes were obtained from 71 out of 84 patients (84%). The most frequently reported complaint was the experience of a limited mouth opening persisting (n = 17, 23%). The second most reported complaint was the presence of TMJ complaints (n = 13, 18%). In 11 cases, this specific complaint consisted of intermittent clicking of the TMJ that was not present before the trauma. One patient reported intermittent creptitation of the TMJ, and another complained about intermittent luxation of the TMJ.

Eleven patients (15%) reported minimal persisting changes in occlusion; they did not consider this a hindrance in their daily lives. Seven patients (9%) reported a change in their facial symmetry. Mental nerve dysfunction persisted in 2 patients (3%). Secondary treatment not indicated during follow-up was reported in 3 cases (4%): secondary ORIF at another center, correction of occlusal contacts by the dentist, and physiotherapy.

All nine pediatric patients were treated conservatively. Two patients received additional therapy with MMF (3 and 8 weeks). One patient who had received MMF for 3 weeks presented with a limited mouth opening of 12 mm 1 year after the trauma due to ankylosis of the left TMJ. No other persistent symptoms were observed in children at the end of follow-up or in the patient-reported outcomes.

We compared fractures abiding by the criteria according to Mathes[

9] for surgical treatment but were treated conservatively and fractures indicated for conservative treatment that were treated conservatively, this for both short-term (13 weeks) and long-term (261 weeks) follow-up.

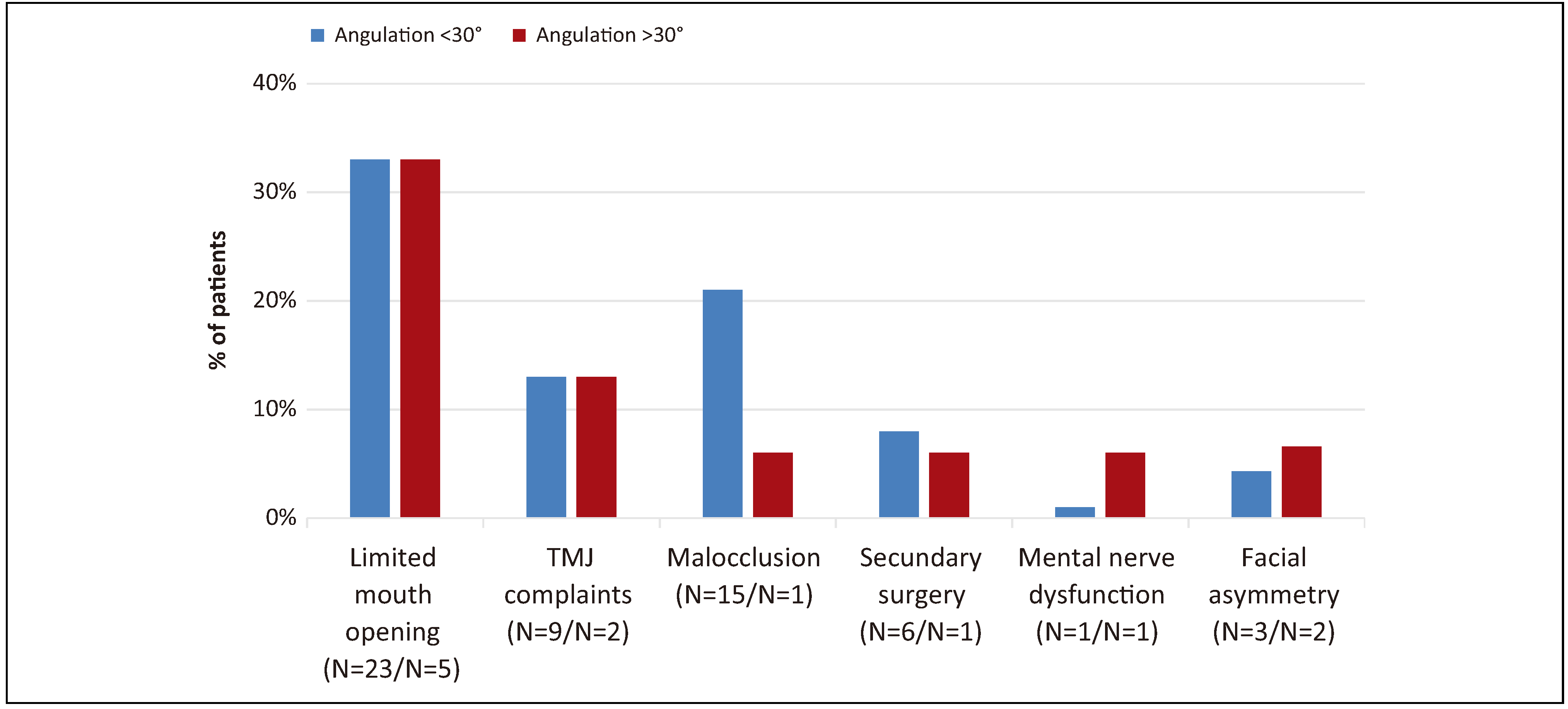

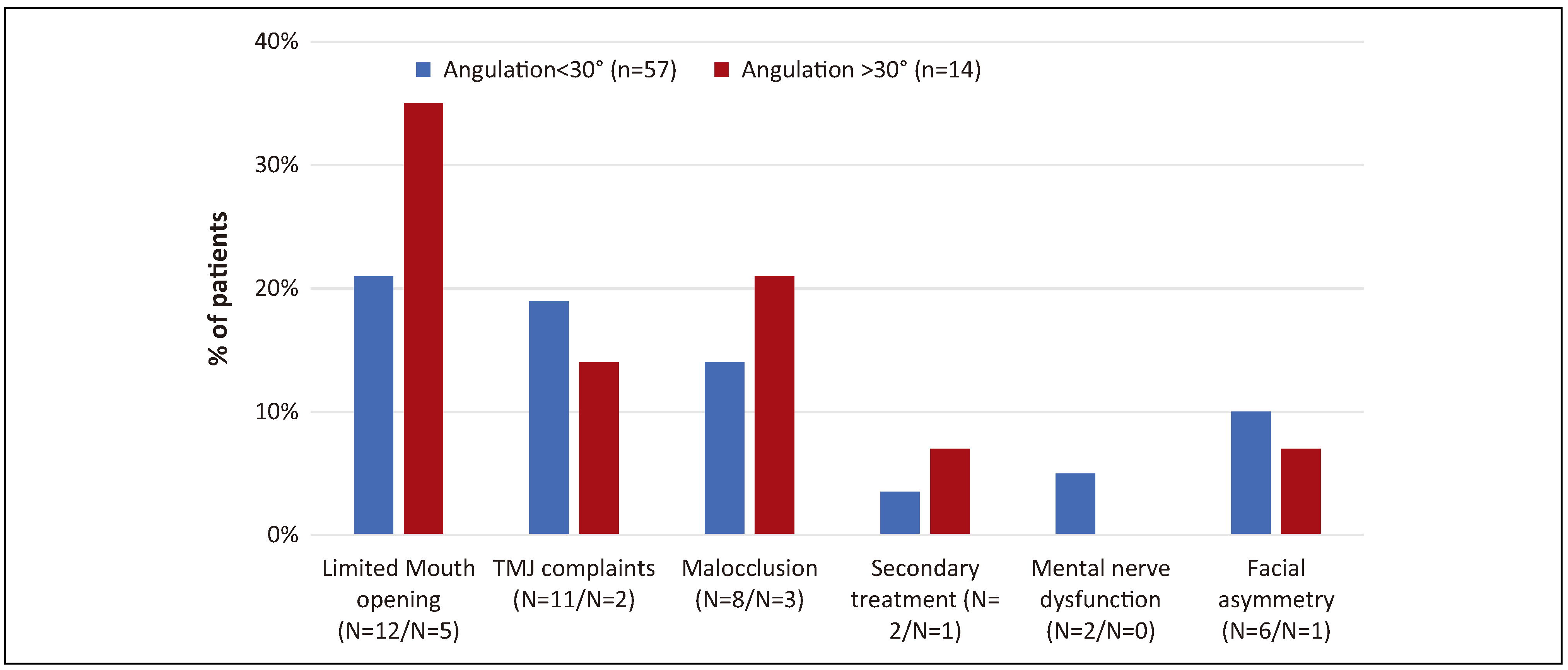

The angulation of the fracture exceeded 30

◦ in 15 patients. At the end of clinical follow-up, those indicated for surgery according to this criterium and those not indicated were compared (

Figure 4). Fourteen patients from the indicated group were contacted for telephone follow-up versus 57 in the non-indicated group (

Figure 5). At the end of clinical follow-up, 5 patients in the indicated group presented with a limited mouth opening versus 23 in the nonindicated group. In the long term, this changed to 12 in the non-indicated group, whereas the number of patients in the indicated group remained constant. At the end of clinical follow-up, 1 patient in the indicated group presented with persisting occlusal changes versus 15 in the non-indicated group. In the long term, this changed to 3 in the indicated group, whereas the number of patients in the non-indicated group decreased to 8. The difference in the number of patients presenting with a limited mouth opening (

P = .029) and occlusal changes (

P =.018) was significant in the short-term; however, the difference became insignificant at the patient-reported outcome. No other parameters were significant at any given time.

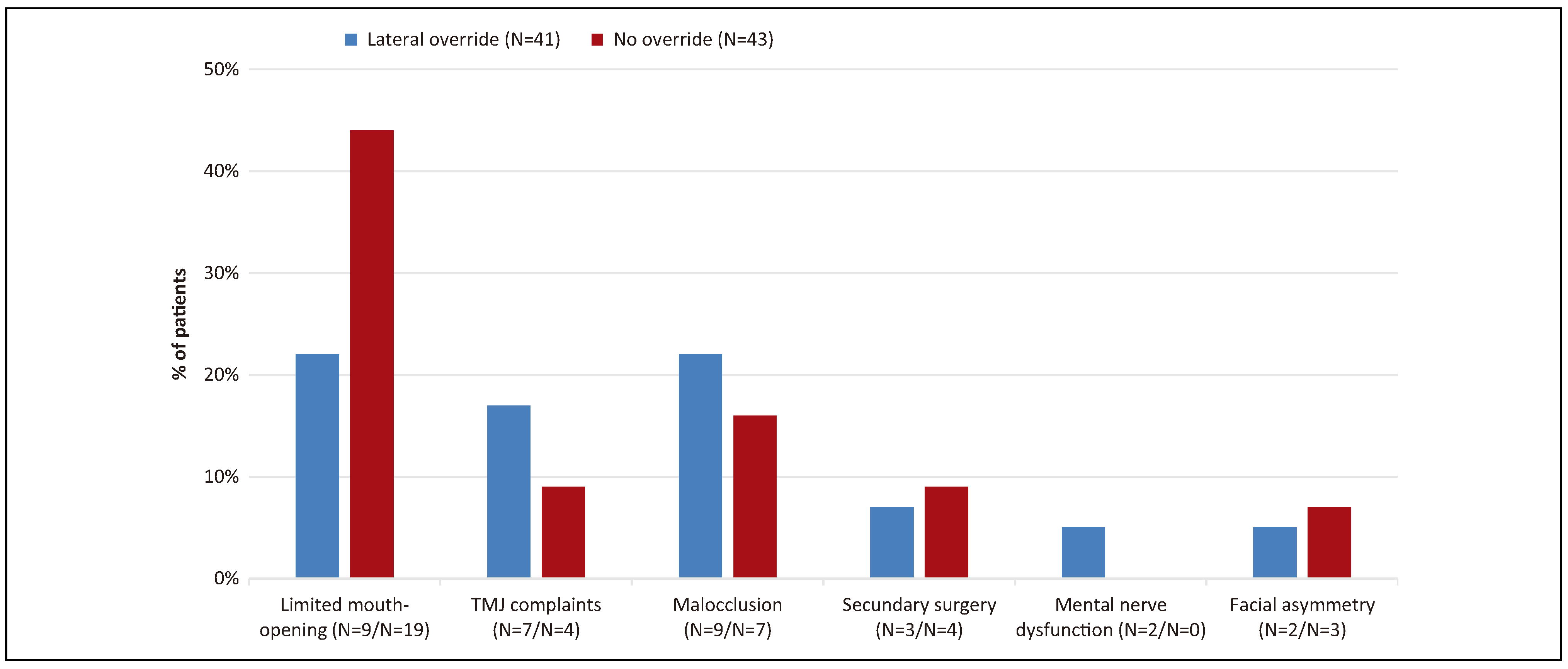

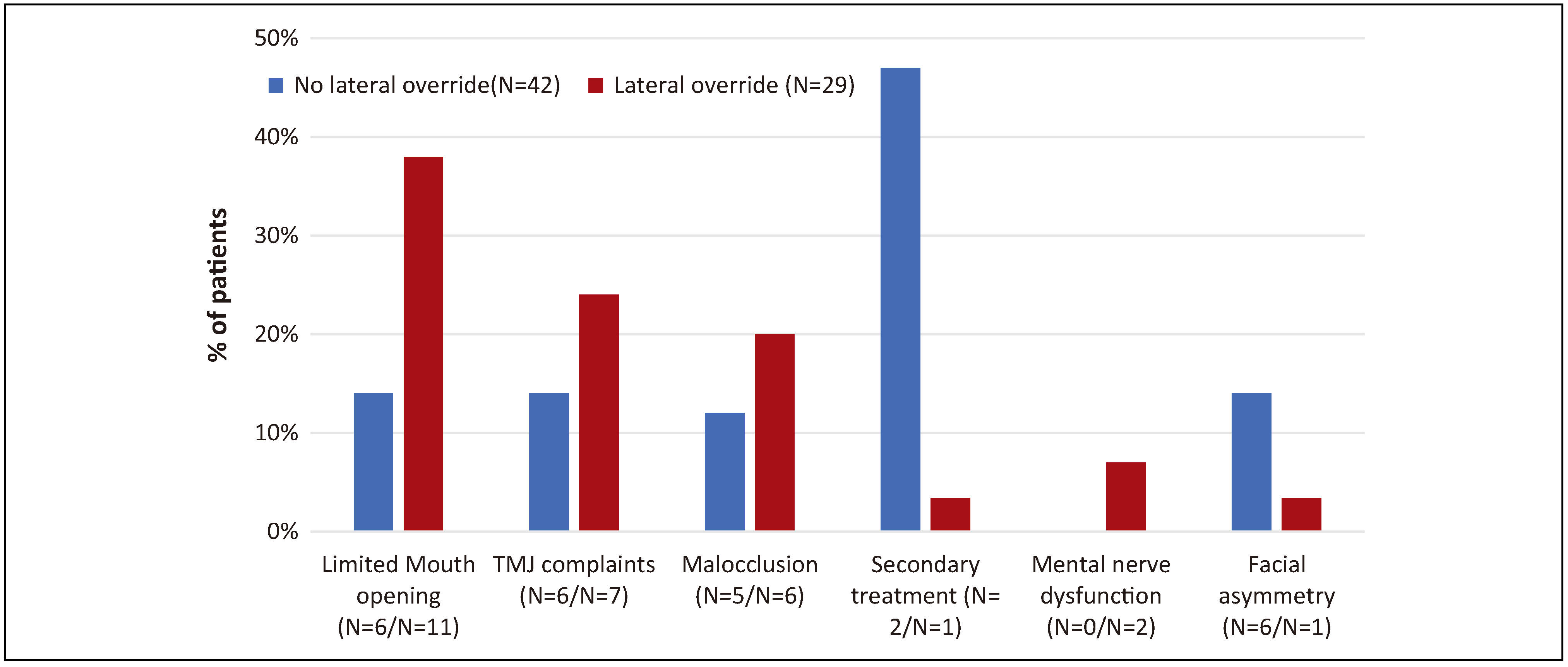

Lateral override of fracture fragments was observed in 41 patients. At the end of clinical follow-up, those indicated for surgery according to this criterium and those not indicated were compared (

Figure 6). Twentynine patients from the indicated group were contacted for telephone follow-up versus 42 in the non-indicated group (

Figure 7). At the end of clinical follow-up, 9 patients in the indicated group had a limited mouth opening versus 19 in the non-indicated group. At the patient-reported outcome, 11 patients in the indicated group experienced a limited mouth opening versus 6 in the non-indicated group (

P = .024). No other parameters were significant at any given time.

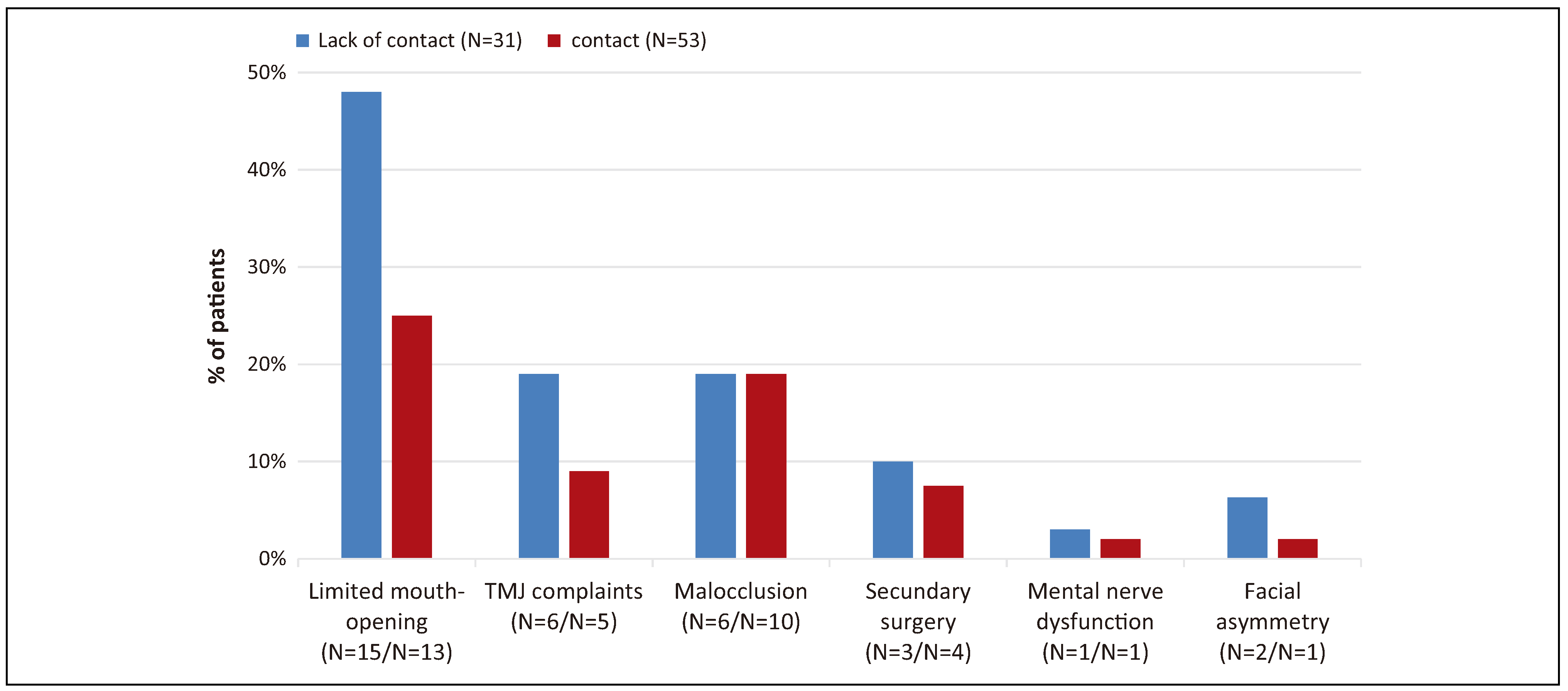

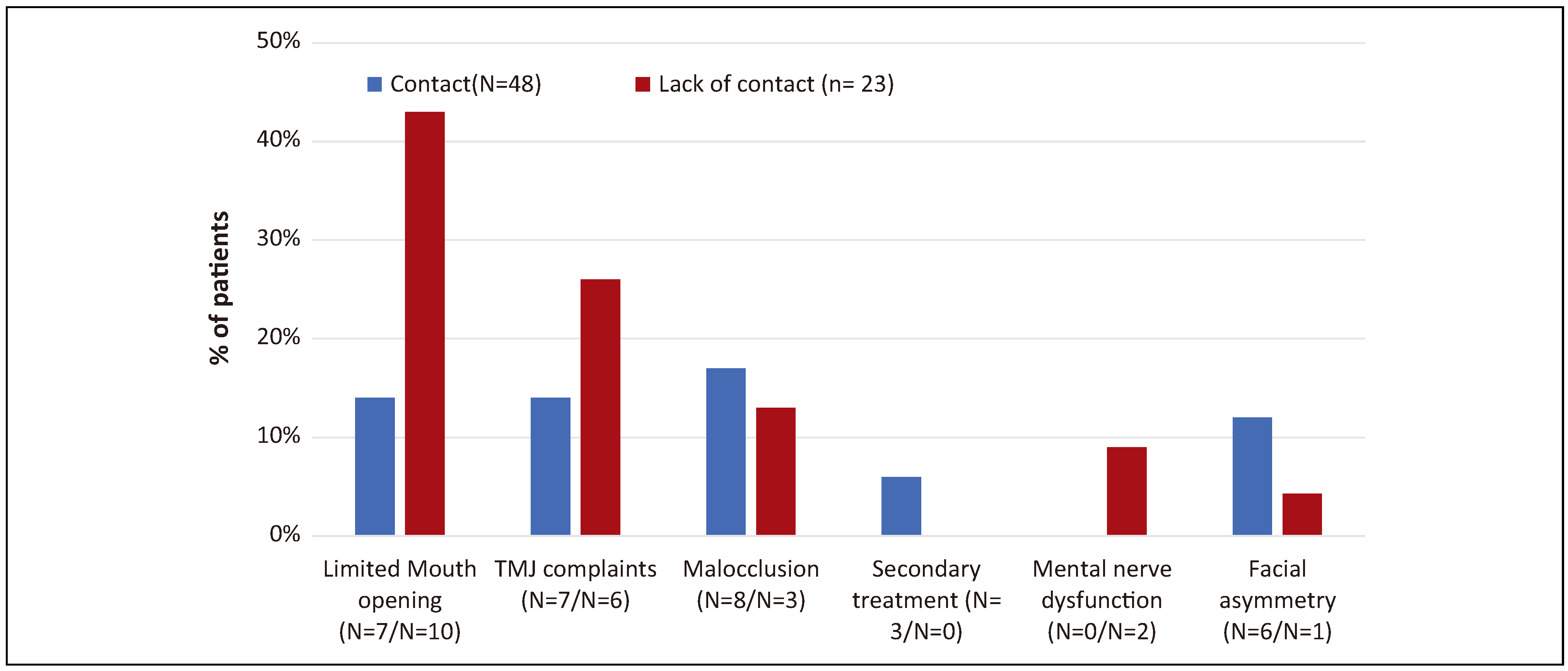

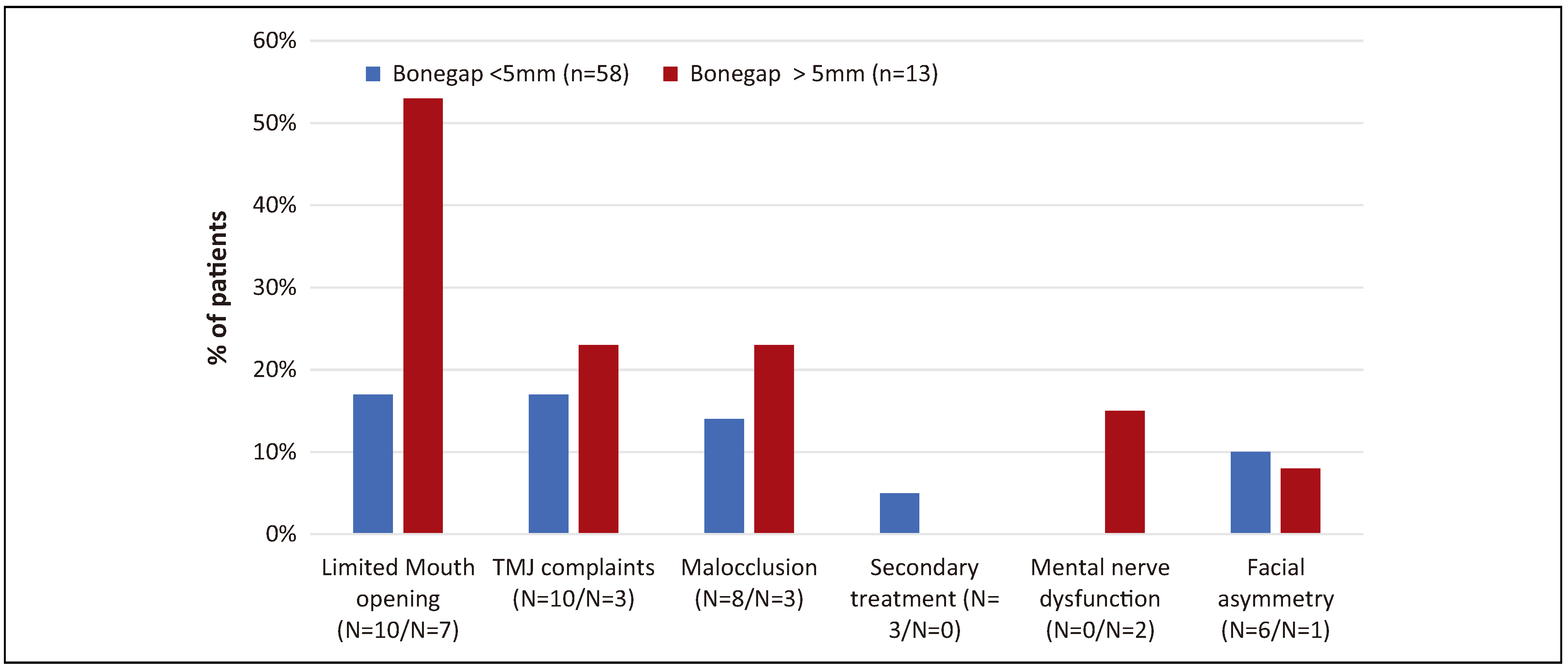

Lack of contact between fragments was observed in 31 patients. At the end of clinical follow-up, those indicated for surgery according to this criterium and those not indicated were compared (

Figure 8). Twenty-three patients from the indicated group were contacted for telephone follow-up versus 48 in the non-indicated group (

Figure 9). At the end of clinical follow-up, 15 patients in the indicated group had a limited mouth opening versus 13 in the nonindicated group. At the patient-reported outcome, 10 patients in the indicated group experienced a limited mouth opening versus 7 in the non-indicated group. In the shortterm, no significant difference in outcome was reported; however, at the patient-reported outcome, a significant difference was found in the number of patients reporting a limited mouth opening (

P = .026). No other parameters were significant at any given time.

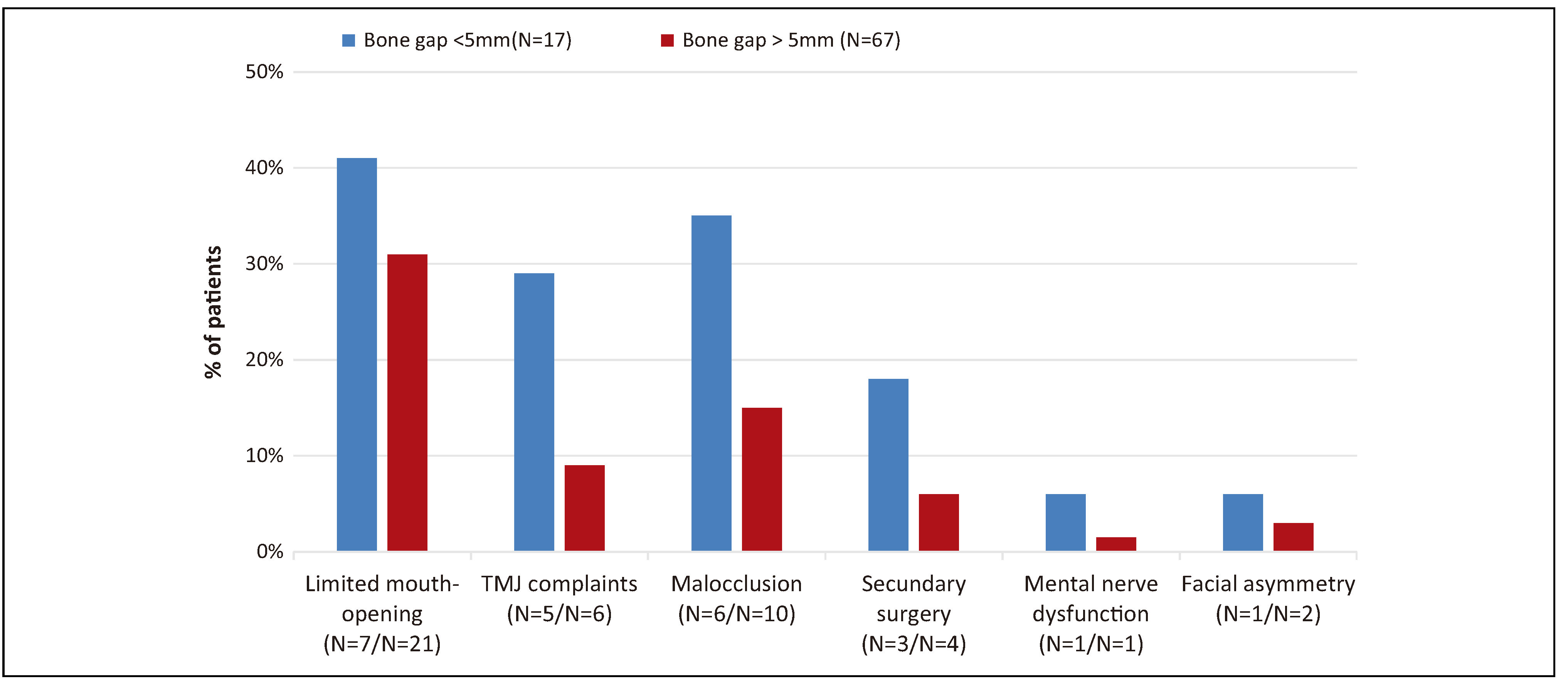

A distance of more than 5 mm between fragments was observed in 17 patients. At the end of clinical follow-up, those indicated for surgery according to this criterium and those not indicated were compared (

Figure 10). Thirteen patients from the indicated group were contacted for telephone follow-up versus 58 in the non-indicated group (

Figure 11). At the end of clinical follow-up, 7 patients in the indicated group had a limited mouth opening versus 21 in the non-indicated group. At the patient-reported outcome, 7 patients in the indicated group experienced a limited mouth opening versus 10 in the non-indicated group. In the short-term, no significant difference in outcome was reported; however, at the patient-reported outcome, a significant difference was found in the number of patients reporting a limited mouth opening (

P = .020). No other parameters were significant at any given time.

Discussion

Sociodemographic factors are among the most important factors influencing epidemiological analysis, and they should always be considered. Leuven is an urban area in a first world country. It is located near the crossing of two major Belgian highways. Due to the presence of the university, the city has a long tradition of cyclists being the predominant users of the road. This explains the relatively high number of cycling accidents (80%) compared to other road traffic accidents (20%).

Another observation is that associated fractures are more frequent in bilateral fractures than unilateral fractures (57% vs 25%). Corresponding with the findings of Lindahl et al,[

14] this is consistent with associated fractures being more prevalent in bilateral cases than unilateral cases, as the velocity and force of impact are usually greater in these cases.

A case review by Zachariades et al[

15] found that (para)-symphyseal, mandibular body, and midface fractures are the most frequent associated fractures, which was confirmed in the present study. They concluded that condylar fractures associated with at least one other mandibular fracture could result from a direct force on the mandible in which the force of impact is not fully absorbed at the location of impact (e.g., symphysis).[

15]

The current trend in fracture treatment is shifting more toward surgical interventions, especially for extracapsular, displaced fracture in the adult patient.[

2,

8,

9] In 2001, Haug and Assael[

16] proposed a list of absolute and relative indications and contra-indications for ORIF.

However, these indications are not universally accepted. Surgeon experience is one of the determining factors. Surgeons operating in the condylar area should have sufficient experience in order to achieve good results; without sufficient experience, they might be more inclined to take a more conservative approach. Therefore, treatment choice remains up to the surgeon’s preference and experience and, as such, treatment protocols are varied.[

2,

8,

9,

16]

Notably, when comparing conservatively indicated fractures and those indicated for surgery, a limited mouth opening was the only significantly different outcome parameter with the long-term patient-reported outcome. However, any limited mouth opening could not be objectively measured by clinicians and, when asked about it, none of the patients declared this to be a specific hindrance in their daily activities. Thus, conservative treatment in these cases can be considered a valid alternative if surgery is not desirable.

Treatment of children causes less disagreement. Due to better tissue regeneration capabilities and the possibility of derangement in the still growing TMJ, surgery is rarely necessary and should only be used if there are no other options left.[

9,

12] MMF should be used for the briefest amount of time possible, as early mobilization is key to restoring the joint’s proper function and preventing ankylosis.[

12] Even with conservative treatment approaches advocated in children, long-term observations include condylar sag due to a hypoplastic and displaced condyle, ankylosis, condylar resorption, bifid condyle, and nonunion of bone fragments.

Good treatment outcomes require a pain-free mouth opening >40 mm,[

17] overall good mobility, restoration of occlusion, stable TMJ, osseous union, facial symmetry, adequate speech and swallowing, and an undisturbed facial growth pattern of the face.[

15,

18] If these are achieved, the treatment choice is less important. A follow-up of sufficient length is required to detect any changes as early as possible. We suggest a follow-up of at least 1 year in order to detect ankylosis and other emerging ATM problems in adults and a follow-up of at least 5 years in children.