A Clinical and Radiological Investigation of the Use of Dermal Fat Graft as an Interpositional Material in Temporomandibular Joint Ankylosis Surgery

Abstract

:Introduction

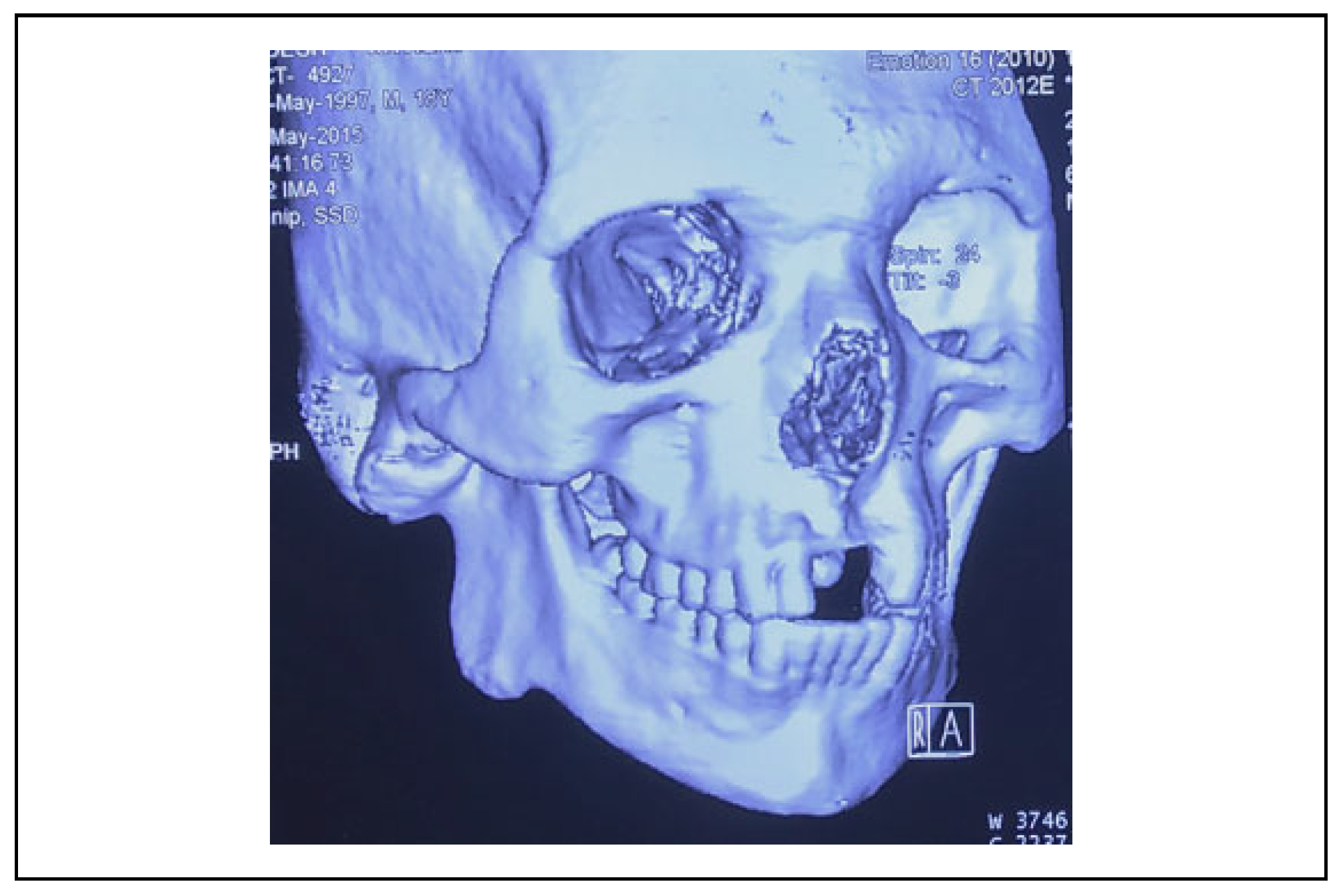

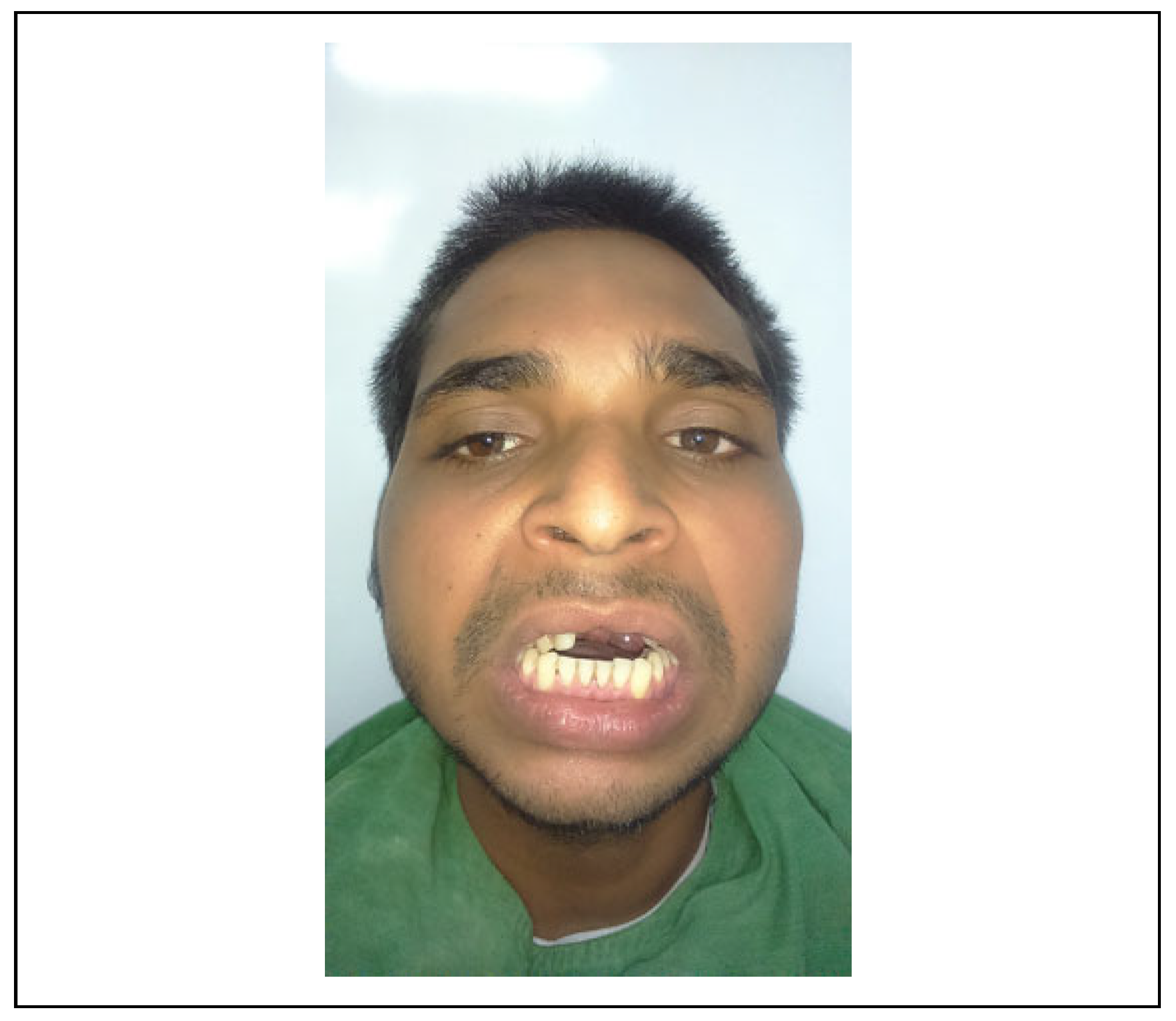

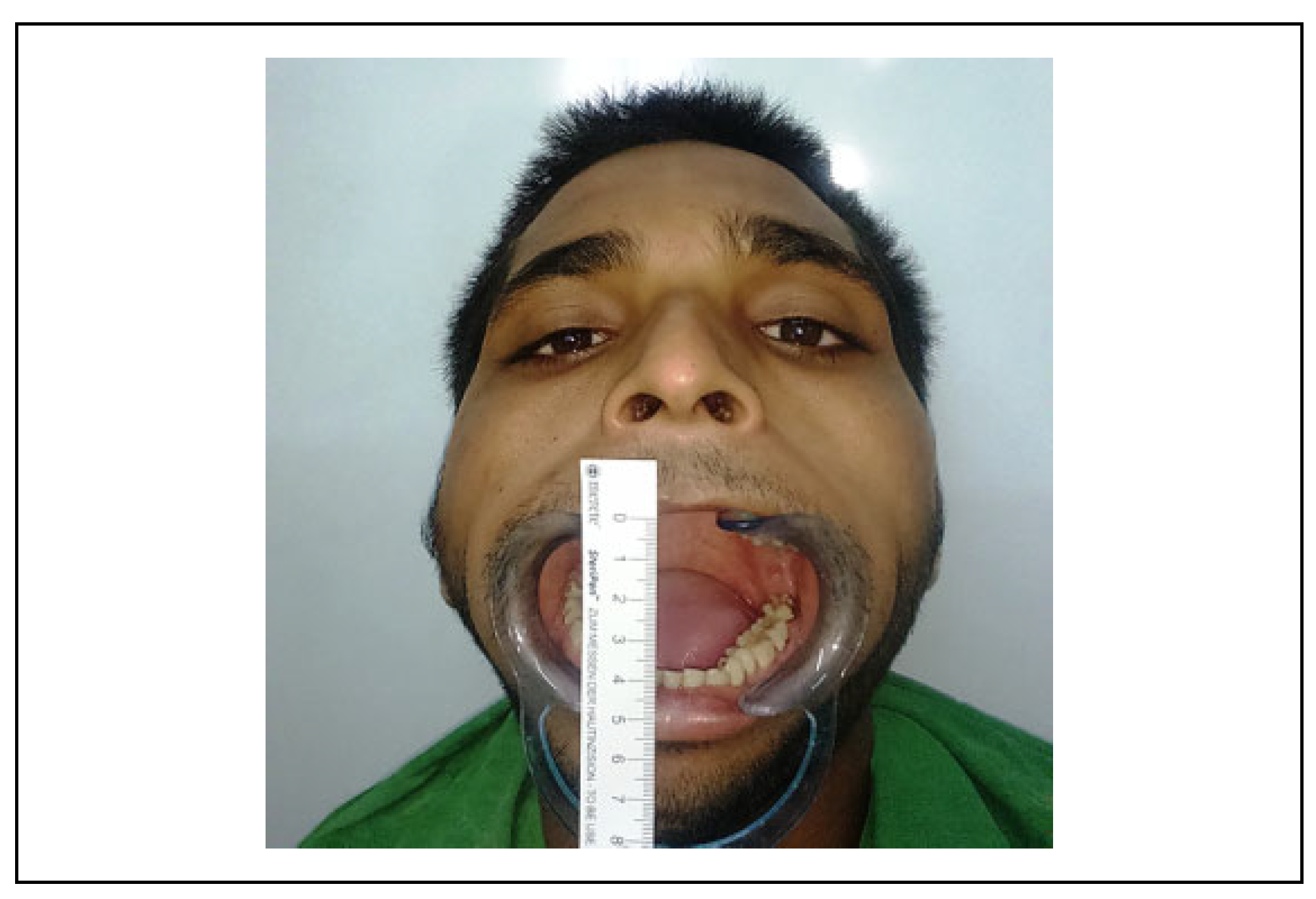

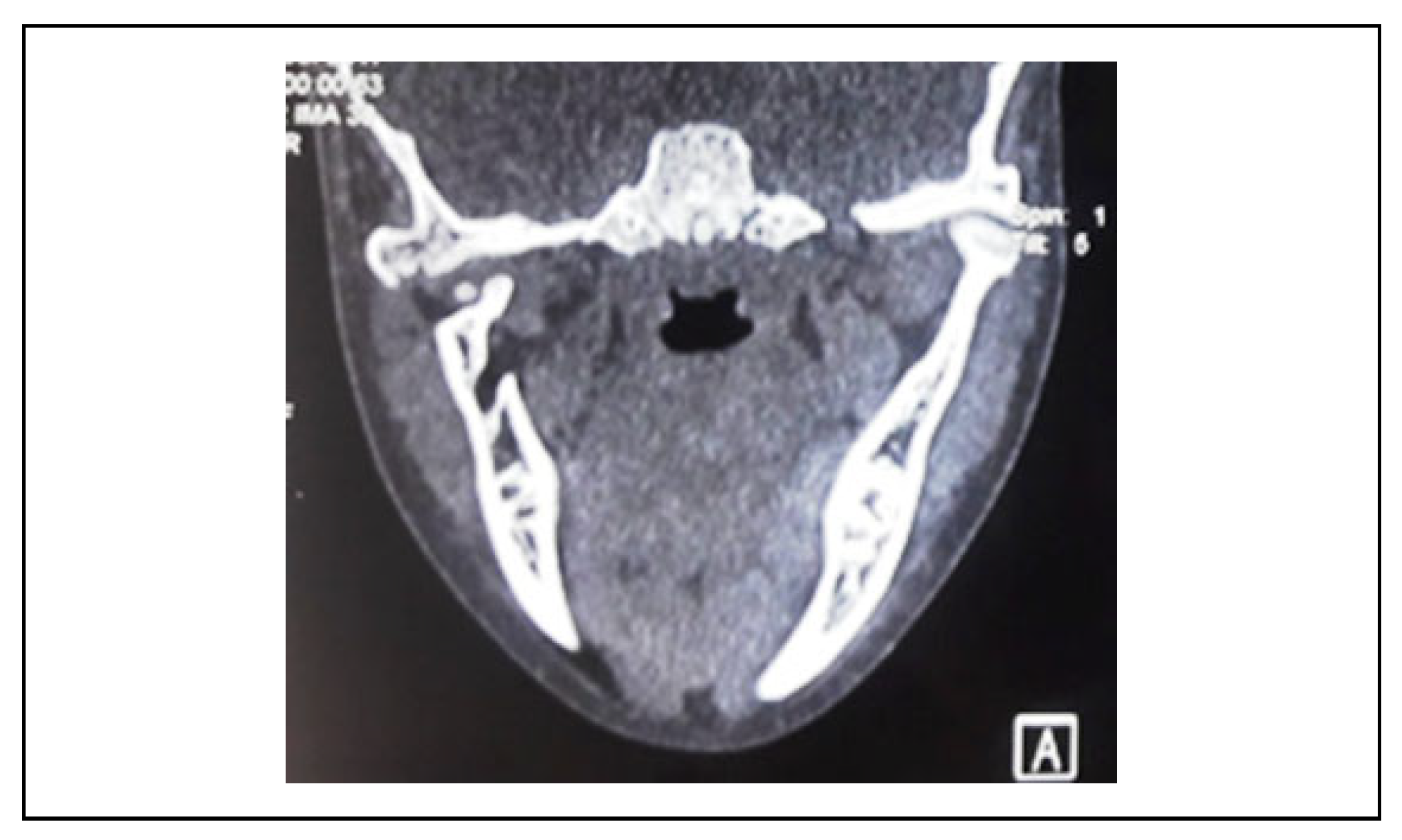

Materials and Method

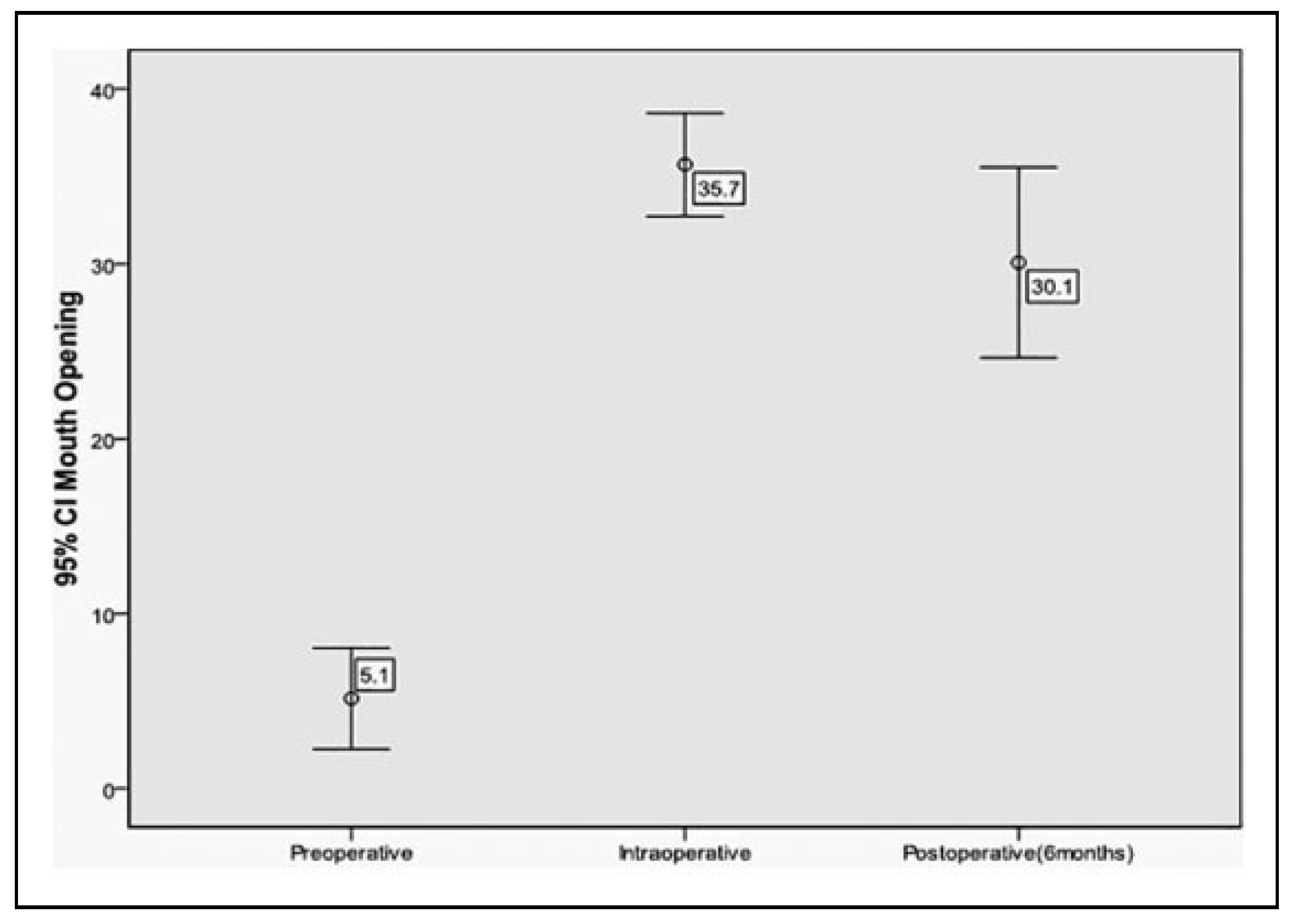

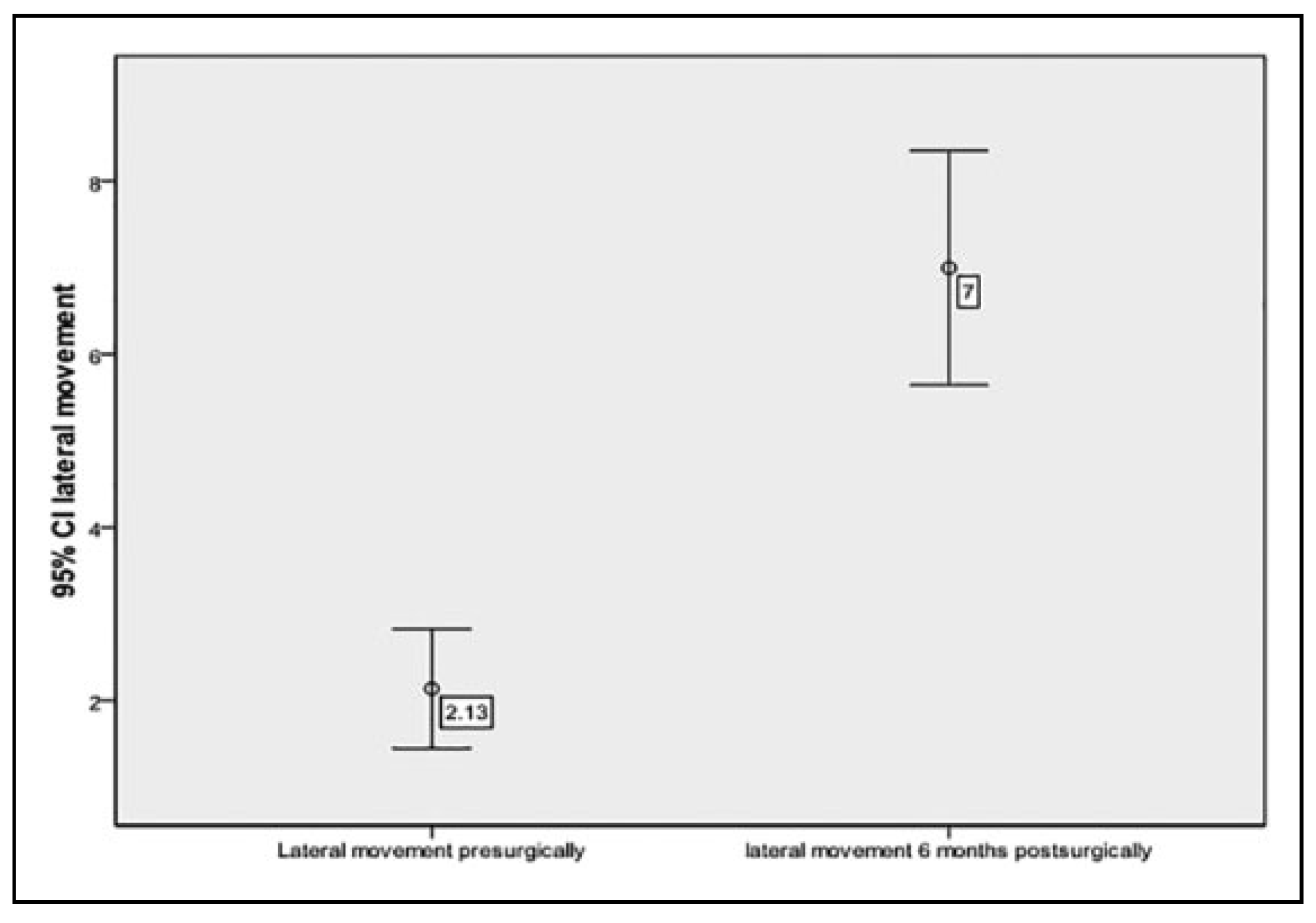

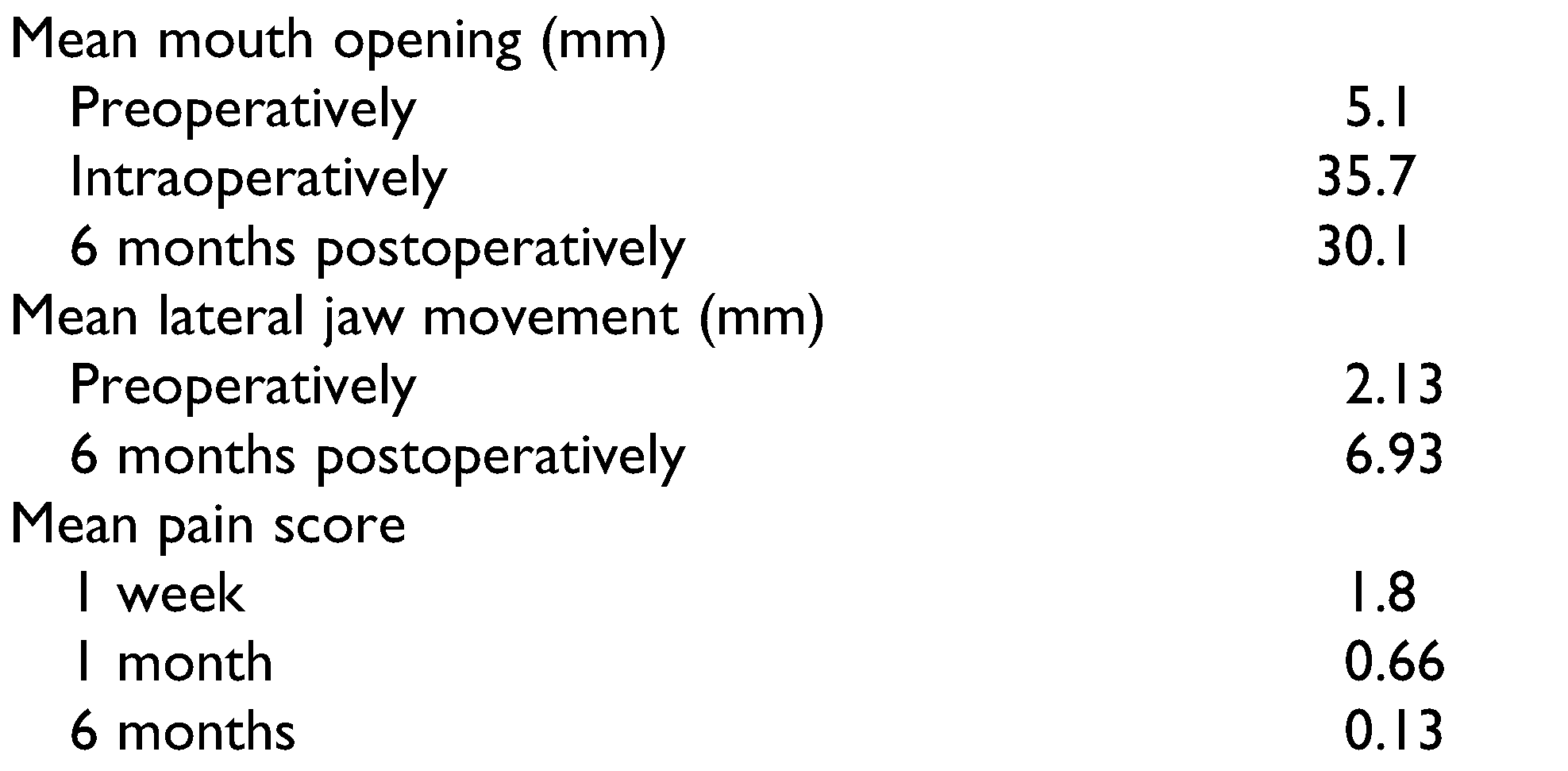

Results

Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Long, X.; Li, X.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Preservation of disc for treatment of traumatic temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005, 63, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchbinder, D.; Currivan, R.B.; Kaplan, A.J.; Urken, M.L. Mobilization regimens for the prevention of jaw hypomobility in the radiated patient: a comparison of three techniques. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993, 51, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, G.A. Monitoring of incremental changes in maximum interincisal opening after gap arthroplasty omits the risk of reankylosis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018, 46, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chuong, R.; Piper, M.A. Cerebrospinal fluid leak associated with proplast implant removal from the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992, 74, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Risdon, F. Ankylosis of the temporo-mandibular joint. J Am Dent Assoc. 1934, 21, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Dolwick, M.F.; Aufdemorte, T.B. Silicone induced foreign body reaction and lymphadenopathy after temporomandibular joint arthroplasty. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985, 59, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannides, C.; Freihofer, H.P.M. Replacement of the damaged inter-articular disc of the TMJ. J Craniomandib Pract. 1988, 16, 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Matukas, V.J.; Lachner, J. The use of autologous auricular cartilage for temporomandibular joint disc replacement: a preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990, 48, 348–353. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, N.A.; MacMillan, C.; Buckley, M.J.; Barnes, L. Histological and histochemical changes in failed auricular cartilage grafts used for a temporomandibular joint disc replacement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997, 55, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuka, S.; Narinobou, M.; Nakagawa, K.; Yamamoto, E. Histological evaluation of auricular cartilage grafts after discectomy in the rabbit craniomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996, 54, 1216–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Yih, W.-Y.; Zysset, M.; Merrill, R.G. Histopathological study of fate of autogenous auricular cartilage grafts in the human temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992, 50, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stewart, H.M.; Hann, J.R.; DeTomasi, D.C.; Neville, B.W.; DeChamplain, R.W. Histological fate of dermal grafts following implantation for temporomandibular joint meniscal perforation: a preliminary study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986, 62, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muto, T.; Tomioka, K.; Michiya, H.; Kanazawa, M. Epidermoid cyst in the temporomandibular joint after dermal graft. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1992, 20, 270–272. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitroulis, G. The use of dermis grafts after discectomy for internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005, 63, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Popescu, V.; Vasiliu, D. Treatment of temporomandibular ankyloses with particular reference to the interposition of full thickness skin autotransplant. J Maxillofac Surg. 1977, 5, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chossegros, C.; Guyot, L.; Cheynet, F.; Blanc, J.L.; Cannoni, P. Full-thickness skin graft interposition after temporomandibular joint ankylosis surgery: a study of 31 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999, 28, 330–334. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitroulis, G.; Slavin, J. Histological evaluation of full thickness skin as an interpositional graft in the rabbit craniomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006, 4, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura, S.; Fujita, K. Modification of the temporalis muscle and fascia flap for the management of ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996, 54, 794–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogrel, M.A.; Kaban, L.B. The role of a temporalis fascia and muscle flap in temporomandibular joint surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990, 48, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, S.E.; Larsen, P.E. The use of a pedicled temporalis muscle-pericranial flap for replacement of the TMJ disc: preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989, 47, 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Van Akkerveeken, P.F.; Van Der Kraan, W.; Muller, J.W. The fate of the free fat graft: a prospective clinical study using CT scanning. Spine 1986, 11, 501–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aagenskiold, A.; Kiviluoto, O. Prevention of epidural scar formation after operations on the lumbar spine by means of free fat transplants: a preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976, 115, 92–95. [Google Scholar]

- Billings, E.; May, J.W. Historical review and present status of free fat graft autotransplantation in plastic and reconstructive surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989, 83, 368–381. [Google Scholar]

- Lexer, E. Zwanzig jahre transplantations furschung in der chirurgie. Langenbecks Arch Klin Chir. 1925, 138, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitroulis, G. The interpositional dermis-fat graft in the management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004, 33, 755–760. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitroulis, G.; McCullough, M.; Morrison, W. Quality of life survey of patients prior to and following temporomandibular joint discectomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010, 68, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

|

© 2020 by the author. The Author(s) 2020.

Share and Cite

Rahman, S.A.; Rahman, T.; Hashmi, G.S.; Ahmed, S.S.; Ansari, M.K.; Sami, A. A Clinical and Radiological Investigation of the Use of Dermal Fat Graft as an Interpositional Material in Temporomandibular Joint Ankylosis Surgery. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2020, 13, 53-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520903876

Rahman SA, Rahman T, Hashmi GS, Ahmed SS, Ansari MK, Sami A. A Clinical and Radiological Investigation of the Use of Dermal Fat Graft as an Interpositional Material in Temporomandibular Joint Ankylosis Surgery. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2020; 13(1):53-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520903876

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahman, Sajjad Abdur, Tabishur Rahman, Ghulam Sarwar Hashmi, Syed Saeed Ahmed, Mohammad Kalim Ansari, and Abdus Sami. 2020. "A Clinical and Radiological Investigation of the Use of Dermal Fat Graft as an Interpositional Material in Temporomandibular Joint Ankylosis Surgery" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 13, no. 1: 53-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520903876

APA StyleRahman, S. A., Rahman, T., Hashmi, G. S., Ahmed, S. S., Ansari, M. K., & Sami, A. (2020). A Clinical and Radiological Investigation of the Use of Dermal Fat Graft as an Interpositional Material in Temporomandibular Joint Ankylosis Surgery. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 13(1), 53-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1943387520903876