Extranasopharyngeal Angiofibroma Arising from the Anterior Nasal Septum in a 35-Year-Old Woman

Abstract

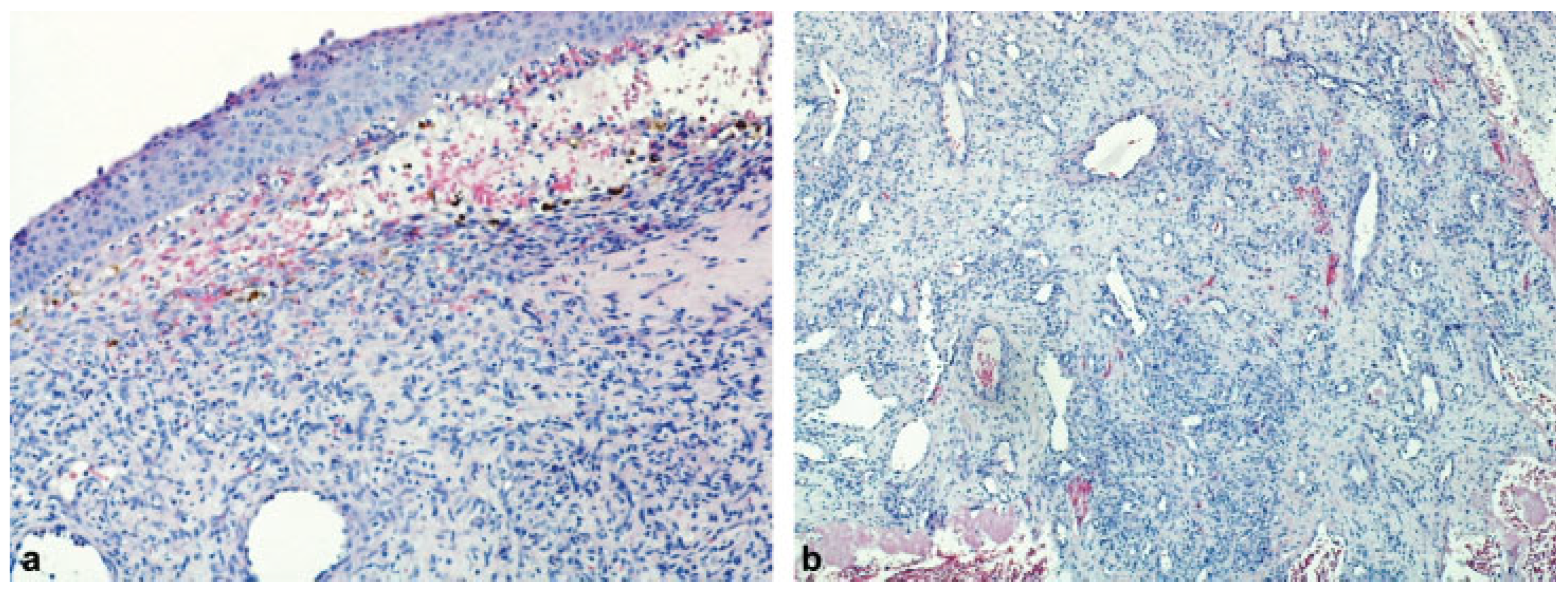

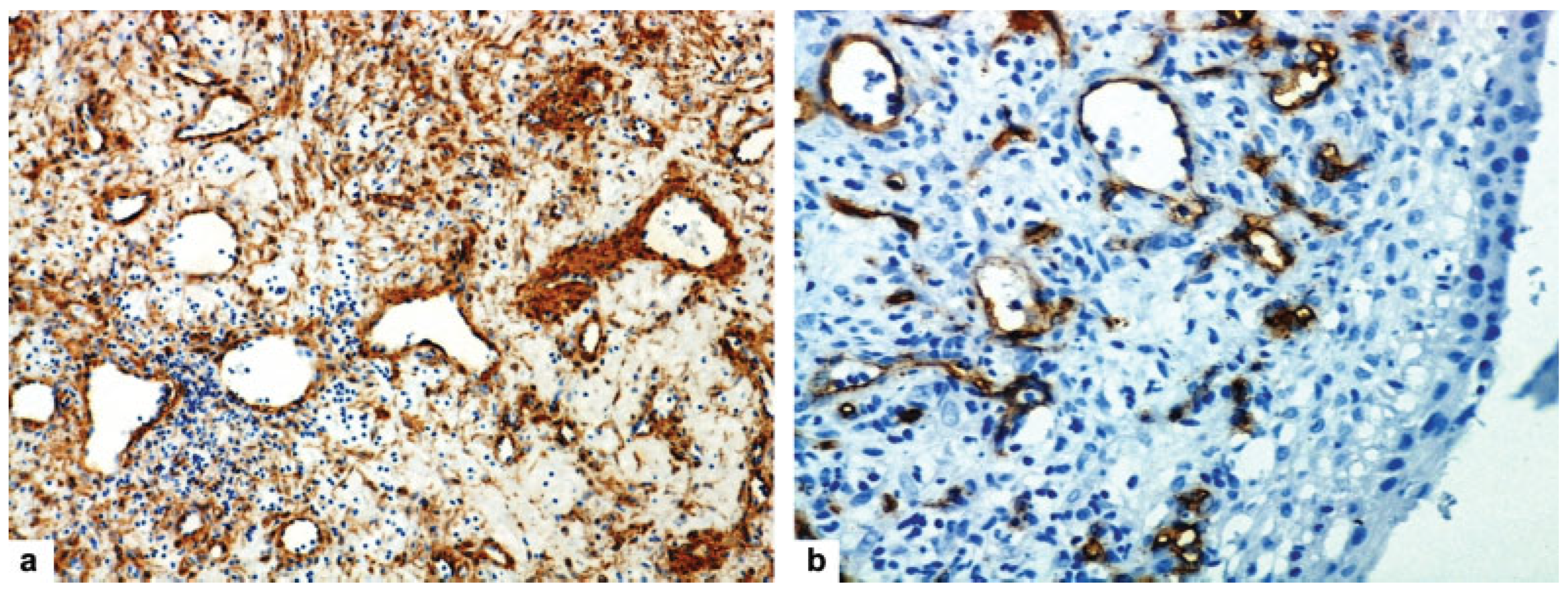

Case Report

Discussion

Conclusion

Previous Presentation

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Windfuhr, J.P.; Vent, J. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma revisited. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2018, 43, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windfuhr, J.P.; Remmert, S. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma: Etiology, incidence and management. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004, 124, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraide, F.; Matsubara, H. Juvenile nasal angiofibroma: A case report. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 1984, 239, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpa, J.R.; Novelly, N.J. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1989, 101, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, K.K.; Kumar, A.; Singh, M.K.; Chhabra, A.H. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma arising from the nasal septum. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2001, 58, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somdas, M.A.; Ketenci, I.; Unlu, Y.; Canoz, O.; Guney, E. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma originating from the nasal septum. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2005, 133, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, M.P.; Timmons, C.F.; McClay, J.E. Autoamputation of an extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma arising from the nasal septum. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. Extra 2006, 1, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohindra, S.; Grover, G.; Bal, A.K. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the nasal septum: A case report. Ear Nose Throat J. 2009, 88, E17–E19. [Google Scholar]

- Uyar, M.; Turanli, M.; Pak, I.; Bakir, S.; Osma, U. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma originating from the nasal septum: A case report. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis. Derg. 2009, 19, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan, A.L.; Moukarbel, R.V.; Kattan, M.; Natout, M. Angiofibroma of the nasal septum. Middle East. J. Anaesthesiol. 2012, 21, 653–655. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rodriguez, L.; Rudman, K.; Cogbill, C.H.; Loehrl, T.; Poetker, D.M. Nasal septal angiofibroma, a subclass of extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2012, 33, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, F.G.; Simões, J.C.; Mendes-Neto, J.A.; Seixas-Alves, M.T.; Gregório, L.C.; Kosugi, E.M. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the nasal septum–uncommon presentation of a rare disease. Rev. Bras. Otorrinolaringol. (Engl. Ed.) 2013, 79, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doğan, S.; Yazici, H.; Baygit, Y.; Metin, M.; Soy, F.K. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the nasal septum: A rare clinical entity. J. Craniofac, Surg. 2013, 24, e390–e393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, S.; Bayraktar, C.; Yıldız, L. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the posterior nasal septum: A rare clinical entity. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis. Derg. 2013, 23, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Akbas, Y.; Anadolu, Y. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the head and neck in women. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2003, 24, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasca, I.; Compadretti, G.C. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma of nasal septum. A controversial entity. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2008, 28, 312–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ewe, S.; Dayana, F.; Fadzilah, F.M.; Gendeh, B.S. Nasal septal angiofibroma in a post-menopausal woman: A rare entity. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, MD03–MD05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.B.; Shukla, S.; Kumari, P.; Shukla, I. A rare case of extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the septum in a female child. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2018, 132, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, L.; Brandwein, M.; Som, P.M. Diseases of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and nasopharynx. In Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck; Barnes, L., Ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 440–516. [Google Scholar]

- Schick, B.; Veldung, B.; Wemmert, S.; et al. p53 and Her-2/neu in juvenile angiofibromas. Oncol. Rep. 2005, 13, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beham, A.; Beham-Schmid, C.; Regauer, S.; Auböck, L.; Stammberger, H. Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: True neoplasm or vascular malformation? Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2000, 7, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, M. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: A theory of pathogenesis. Laryngoscope 1959, 69, 981–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, A.; Jovanovski, A.; Vukomanović Đurđević, B. Giant angiomatous choanal polyp originating from the middle turbinate: A case report. ENT Updates 2017, 7, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilch, B.Z. Soft tissue pathology of the head and neck. In Head and Neck Surgical Pathology; Keel, S.B., Rosenberg, A.E., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001; pp. 389–430. [Google Scholar]

- Perić, A.; Sotirović, J.; Cerović, S.; Zivić, L. Immunohistochemistry in diagnosis of extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma originating from nasal cavity: Case presentation and review of the literature. Acta Med. (Hradec Kralove) 2013, 56, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoi, H.; Arakawa, A.; Kuribayashi, K.; Inoshita, A.; Haruyama, T.; Ikeda, K. An immunohistochemical study of sinonasal hemangiopericytoma. Auris Nasus Larynx 2011, 38, 743–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, A.; Baletić, N.; Cerović, S.; Vukomanović-Durdević, B. Middle turbinate angiofibroma in an elderly woman. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2009, 66, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2018 by the author. The Author(s) 2018.

Share and Cite

Kujundžić, T.; Perić, A.; Đurđević, B.V. Extranasopharyngeal Angiofibroma Arising from the Anterior Nasal Septum in a 35-Year-Old Woman. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2019, 12, 141-145. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1675809

Kujundžić T, Perić A, Đurđević BV. Extranasopharyngeal Angiofibroma Arising from the Anterior Nasal Septum in a 35-Year-Old Woman. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2019; 12(2):141-145. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1675809

Chicago/Turabian StyleKujundžić, Tarik, Aleksandar Perić, and Biserka Vukomanović Đurđević. 2019. "Extranasopharyngeal Angiofibroma Arising from the Anterior Nasal Septum in a 35-Year-Old Woman" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 12, no. 2: 141-145. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1675809

APA StyleKujundžić, T., Perić, A., & Đurđević, B. V. (2019). Extranasopharyngeal Angiofibroma Arising from the Anterior Nasal Septum in a 35-Year-Old Woman. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 12(2), 141-145. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1675809