Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Experience in Otolaryngology Residency: A National Survey of Program Directors

Abstract

:Materials and Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

Abstract for Oral Presentation

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Survey: craniomaxillofacial trauma experience in U.S. otolaryngology residency

- 1.

- In what region of the country is your otolaryngology residency program located?

- A.

- Northeast (CT, MA, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT).

- B.

- South (AL, AR, DC, DE, FL, GA, KY, LA, MD, MS, NC, OK, SC, TN, TX, VA, WV).

- C.

- Midwest (IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, WI).

- D.

- West (AK, AZ, CA, CO, HI, ID, MO, NM, OR, NV, UT, WA, WY).

- E.

- United States territories (Puerto Rico, Guam, Samoan Islands).

- F.

- Other.

- 2.

- Do your residents rotate at a level 1 trauma center?

- A.

- Yes.

- B.

- No.

- 3.

- How many residents does your program have per year?

- A.

- 1.

- B.

- 2.

- C.

- 3.

- D.

- 4.

- E.

- 5.

- F.

- 6.

- G.

- 7.

- H.

- Other.

- 4.

- Does your otolaryngology department cover craniomaxillofacial (CMF) trauma?

- A.

- Yes.

- B.

- No.

- 5.

- Does your program curriculum include pediatric CMF trauma?

- A.

- Yes.

- B.

- No.

- 6.

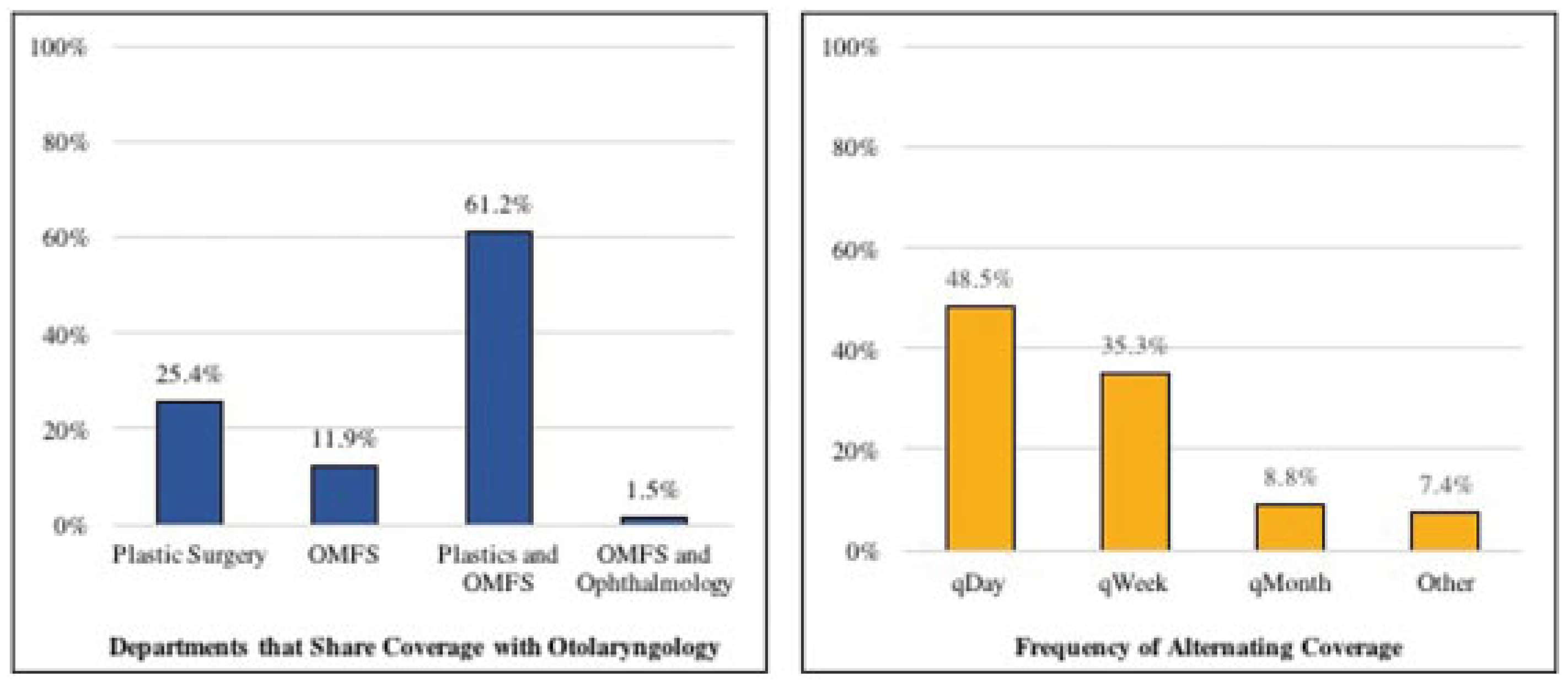

- If your answer was yes to Question 4, does your residency program share coverage of the CMF trauma cases with other specialties?

- A.

- Yes.

- B.

- No.

- C.

- Answered “no” to Question 4.

- 7.

- If your answer wasyesto Questions 4 and 6, with which other programs do you share coverage of the CMF trauma cases? More than one option may be selected. If not listed, please specify.

- A.

- Plastic surgery.

- B.

- Oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMFS).

- C.

- Trauma surgery.

- D.

- Answered “no” to Question 4.

- E.

- Other.

- 8.

- If your answer was yes to Question 6, how is the coverage of the CMF trauma divided among the services? If not listed, please specify.

- A.

- Alternating days (q day).

- B.

- Alternating weeks (q week).

- C.

- Alternating months (q month).

- D.

- Answered “no” to Question 6.

- E.

- Other.

- 9.

- If your otolaryngology program does not cover CMF trauma, how do the residents get exposure to CMF trauma, particularly mandible/midface fractures? If your answer is no, please specify.

- A.

- My program does cover CMF trauma.

- B.

- Other.

- 10.

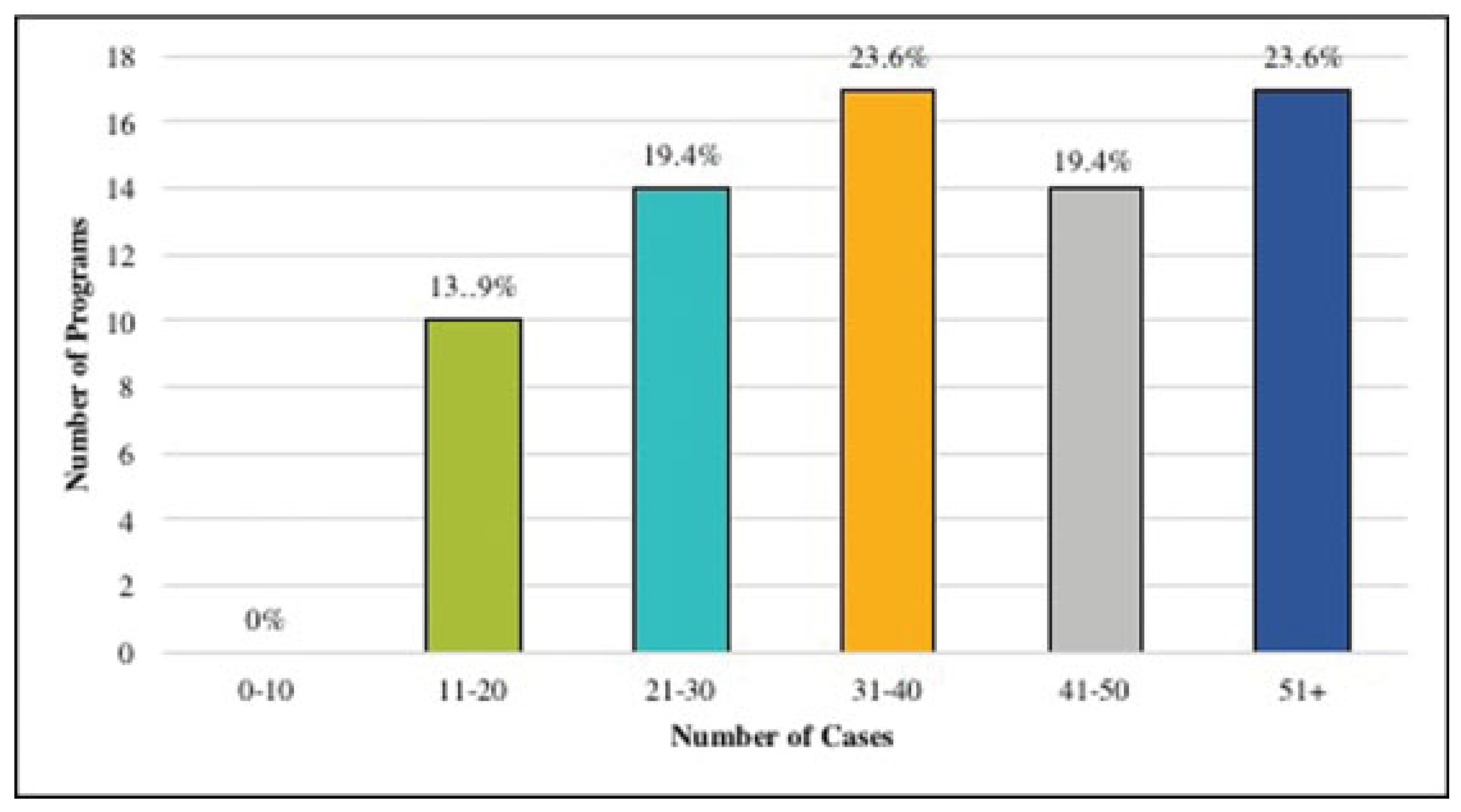

- On average, how many cases of CMF trauma do residents log before graduation?

- A.

- None.

- B.

- 0–10 cases.

- C.

- 11–20 cases.

- D.

- 21–30 cases.

- E.

- 31–40 cases.

- F.

- 41–50 cases.

- G.

- 51+ cases.

- 11.

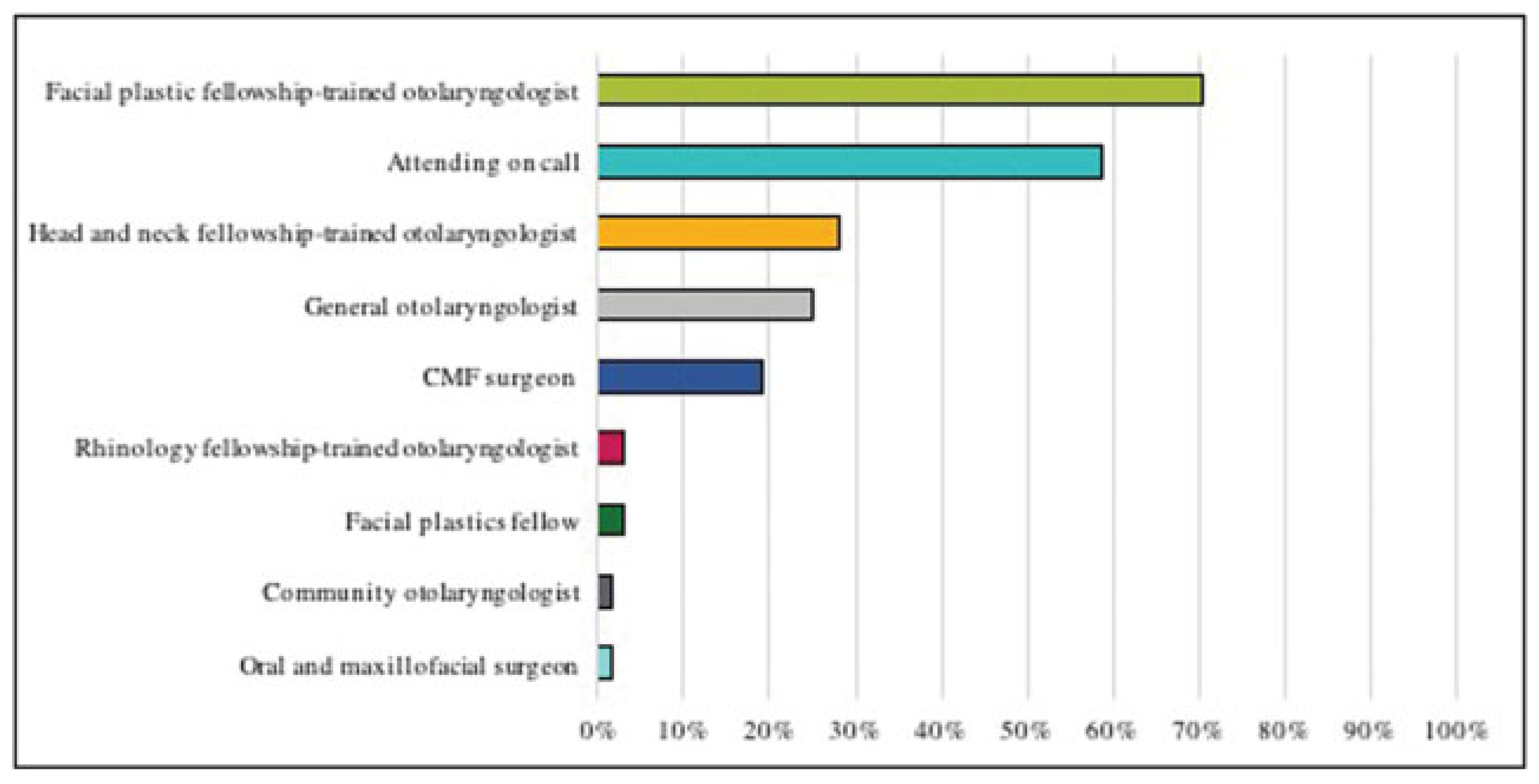

- Regarding coverage of the CMF cases, who staffs the majority of the cases? If the coverage is evenly shared, more than one option may be selected.

- A.

- Attending on call.

- B.

- CMF surgeon.

- C.

- Head and neck fellowship-trained otolaryngologist.

- D.

- General otolaryngologist.

- E.

- Communityotolaryngologist (adjunct clinical faculty).

- F.

- Facial plastic fellowship-trained otolaryngologist.

- G.

- Other.

- 12.

- Is any member of the faculty in your otolaryngology department an active participant of AO Foundation (AOCMF North America)?

- A.

- Yes.

- B.

- No.

- C.

- Unknown.

- D.

- Other.

- 13.

- What percentage of your residency-dedicated didactic lecture time is allocated to CMF trauma?

- A.

- <10%.

- B.

- 11–25%.

- C.

- >25%.

- D.

- Other.

- 14.

- Do your residents have the opportunity to attend CMF trauma courses (e.g., an Principles of Operative Treatment of Craniomaxillofacial Trauma and Reconstruction offered by AO CMF)?

- A.

- Yes.

- B.

- No.

- 15.

- Do you feel the CMF training and exposure of the residents in your program is adequate?

- A.

- Very adequate.

- B.

- Somewhat adequate.

- C.

- Neutral.

- D.

- Somewhat inadequate.

- E.

- Very inadequate.

References

- Meara, D.J.; Coffey Zern, S. Simulation in craniomaxillofacial training. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2016, 24, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schvartzman, S.C.; Silva, R.; Salisbury, K.; Gaudilliere, D.; Girod, S. Computer-aided trauma simulation system with haptic feedback is easy and fast for oral-maxillofacial surgeons to learn and use. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 1984–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOCMF. AO Foundation Web site. Available online: https://aocmf. aofoundation.org/Structure/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 2 April 2017).

- Silvestre, J.; Runyan, C.; Taylor, J.A. Analysis of practice settings for craniofacial surgery fellowship graduates in North America. J. Surg. Educ. 2017, 74, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACGME required minimum number of key indicator procedures for graduating residents. [Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Web site.] March 6, 2013. Available online: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramResources/ 280_Required_Minimum_Number_of_Key_Indicator_Proce- dures.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2017).

- American Board of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Comprehensive Core Curriculum. [American Board of Otolaryngology Web site]. October 2007. Available online: http://www.aboto.org/ pub/Core%20Curriculum.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2017).

- American Board of Otolaryngology Oral Examination Candidate Guidelines. [American Board of Otolaryngology Web site]. Available online: http://www.aboto.org/pdf/oral-blue.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2017).

- Tabaee, A.; Anand, V.K.; Stewart, M.G.; Fried, M.P. The rhinology experience in otolaryngology residency: A survey of chief residents. Laryngoscope 2008, 118, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerscher, K.; Tabaee, A.; Ward, R.; Haddad, J., Jr.; Grunstein, E. The residency experience in pediatric otolaryngology. Laryngoscope 2008, 118, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, T.; Shimahara, E.; Cheng, J.; Capasso, R. Sleep medicine clinical and surgical training during otolaryngology residency: A national survey of otolaryngology residency programs. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2011, 145, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crumley, R.L. Survey of postgraduate fellows in otolaryngologyhead and neck surgery. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 1994, 120, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in craniofacial surgery. [Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Web site.]. Available online: http://acgme.org/portals/0/ PFassets/PIFS/361_craniofacial_plastic_surg_2016_1-yr.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2017).

- Patel, N.; Dittakasem, K.; Fearon, J.A. Craniofacial fellowship training: Where are we now? Plast Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 135, 1454–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2018 by the author. The Author(s) 2018.

Share and Cite

Oh, M.S.; Sethna, A.B.; Henriquez, O.A. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Experience in Otolaryngology Residency: A National Survey of Program Directors. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2019, 12, 134-140. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1660442

Oh MS, Sethna AB, Henriquez OA. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Experience in Otolaryngology Residency: A National Survey of Program Directors. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2019; 12(2):134-140. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1660442

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Melissa S., Anita B. Sethna, and Oswaldo A. Henriquez. 2019. "Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Experience in Otolaryngology Residency: A National Survey of Program Directors" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 12, no. 2: 134-140. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1660442

APA StyleOh, M. S., Sethna, A. B., & Henriquez, O. A. (2019). Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Experience in Otolaryngology Residency: A National Survey of Program Directors. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 12(2), 134-140. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1660442