Abstract

Sacrifice of the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) during resection of the mandible is taken as a rule. In 1987, Jensen and Nock described a technique that permitted placement of dental implants in the atrophied mandibular alveolar ridge that lacked sufficient vertical height superior to the mandibular canal. This technique was used by some authors to preserve continuity of the IAN during resection of the mandible in patients with benign tumors. The described techniques are traumatic, time-consuming, and not precise. We propose a new refined technique of preservation of IAN with use of a guide to approach mandibular canal, cutting guides with a slot for a relocated IAN, and a new approach to positioning of the fixating screws. We assessed the effectiveness of this new technique with use of an electro-odontometer. In 21 cases, we demonstrated a refined approach to preservation of the IAN. In 7 patients (33%), the IAN was preserved on one side and in 14 patients (67%), on both sides. Sensation in the lower lip was restored in 18 patients (86%). These patients generally recovered sensation within 22 days postoperatively. This proposed technique makes preservation of IAN easier, faster, less traumatic, and more predictable. In this article, we describe criteria for the patients with cancer of oral mucosa to be admitted for this procedure. Restored sensation in the lower lip of the patients who have undergone resection of the mandible significantly improves their quality of life.

The inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) runs in the mandibular canal and innervates the mandibular molar and premolar teeth and the adjacent gingiva. The nerve exits the mandible as the mental nerve, which innervates the skin of the mental area and lower lip as well as the mucosa and gingiva as far posteriorly as the second premolar.

Resection of the mandible has profound and long-term effects on a patient’s overall health, appearance, and ability to communicate, eat, and swallow. Advances in microvascular reconstruction, three-dimensional (3D) modeling, and dental rehabilitation can lessen these adverse effects. However, the

IAN is often sacrificed during segmental resection of the mandible, leading to permanent loss of sensation in the lower lip. Bilateral IAN injury is especially traumatic to patients.

Permanent loss of sensation in the lower lip results in the inability to feel food and liquid on the lip, articulation problems, and drooling of saliva and liquids. Functions such as kissing, make-up application, and shaving are also affected.[1] Most of these patients can only eat with a mirror in front of them and avoid eating in public places, which negatively impacts their social activity. Some patients can even lose their jobs if public speaking is required. Together, these consequences of IAN injury can cause adverse psychological effects and lower a patient’s quality of life.[2]

IAN injury is considered a serious complication of dental implant surgery. In 1987, Jensen and Nock described a technique that permitted placement of dental implants in the atrophied mandibular alveolar ridge that lacked sufficient vertical height superior to the mandibular canal.[3] This technique also facilitated orthognathic surgery.[4] The procedure includes removal of the bone lateral to the mandibular canal and transposition of the IAN. This technique has been used to preserve continuity of the IAN during segmental mandibulectomy for both benign and malignant lesions.[5,6]

Despite knowing the anatomy, variations of the IAN can make it difficult to identify. The approach requires wide resection of the bone lateral to the mandibular canal, which is time-consuming, traumatic, and inappropriate for patients with tumor invasion of the mandible. A transposed IAN can also become trapped in the canal under the surgical cutting guide. To spare the nerve, the cutting guide is used to mark the level of resection and then removed. The IAN is raised and sawing is performed under the nerve. Resection without the cutting guide, however, can decrease the accuracy of the procedure, making virtual surgical planning (VSP) less effective. The IAN in the remaining mandibular fragments can also be easily injured by screws during fixation of the transplant within the defect.

We have designed a new algorithm for planning and performing resection and primary reconstruction of the mandible that incorporates preservation of the IAN using state-of-the-art technology.

Methods

A 3D model of the mandible was generated with VSP; the location of the IAN was determined and underlined in color if needed. A guide to help approach the mandibular canal was then designed (Figure 1). The upper margin of the guide was placed just under the mandibular canal starting from the mental foramen and ending 1 cm proximal to the planned level of resection. The inner surface of the guide was congruent with the outer surface of the mandible. The guide was then fixed to the mandible with one or two screws for stability. The holes for the drilling sleeves were designed to be 0.2 mmwider than the diameter of the sleeves. The course of the mandibular canal was marked with a burr along the upper margin of the guide (Figure 2), after which the guide was removed. The dissection continued along the marked groove until the embedded IAN was reached and lifted from the canal. After slightly retracting the mental nerve, the incisive branch of the IAN was cut and the proximal branch to the lower lip was left intact. This maneuver allowed the IAN to be transposed out of the mandibular canal (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Designing the guide to approach the mandibular canal.

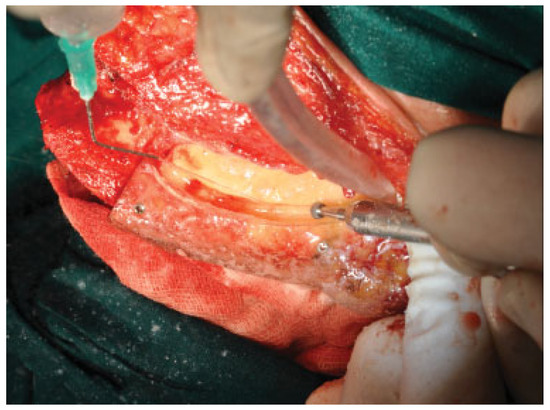

Figure 2.

Marking the course of the mandibular canal with a burr.

Figure 3.

Transposition of the inferior alveolar nerve from the mandibular canal.

By using the typical cutting guides, a transposed IAN can become trapped in the mandibular canal (Figure 4) and damaged during the sawing process. Therefore, we changed the design of these guides by adding a slot (1 cm deep and 5 mm wide) along its anterior margin, in which the transposed IAN would be protected during the sawing of the mandible (Figure 5). With this technique, there was no need to remove the cutting guide and the resection was performed according to the planned level and plane (Figure 6).

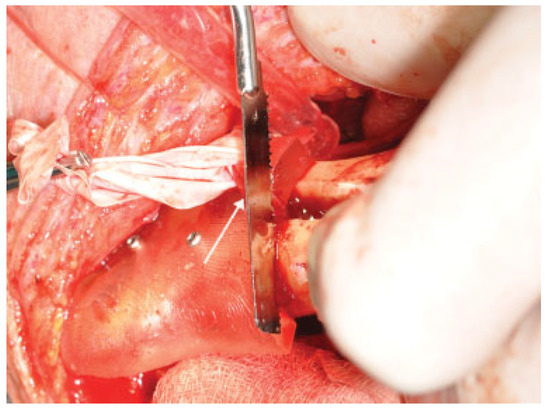

Figure 4.

A transposed inferior alveolar nerve trapped under an unmodified cutting guide.

Figure 5.

Sheltering of the transposed inferior alveolar nerve in the slot along the anterior margin of the cutting guide.

Figure 6.

Sawing of the mandible using the modified cutting guide.

Another important step in preserving the IAN is the careful positioning of fixating screws of the reconstructive plate; the course of the mandibular canal should be considered at this stage. One solution was to create a patient-specific or patient-customized plate. Unfortunately, this product is not widely available due to cost and shipping issues. In our clinic, we utilized a different approach. Once the model of the mandible was completed and the mandibular resection was planned, we designed and shaped the transplant. Standard titanium plates were prebent and attached to the model, and the course of the mandibular canal was marked (Figure 7). The model with the attached plates was then scanned in either a computed tomography or 3D scanner, and the resultant 3D model was used to position the screws. The holes for the drilling sleeves were then created in the cutting guide accordingly (Figure 8).

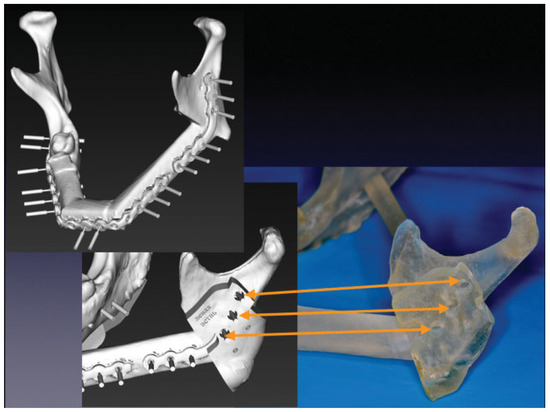

Figure 7.

Model of the mandible with prebent plates attached and the mandibular canal marked.

Figure 8.

Designing the cutting guide with holes for a drilling sleeve.

We assessed the effectiveness of this technique in preserving the IAN using an electro-odontometer (OSP 2.0; Averon, Yekaterinburg, Russia). The accuracy of this device is within 1 µA and its error rate is under 5%. Using a testing current between 1 and 100 mA, the patient’s pain threshold was determined by verbal responses. The passive electrode of the electro-odontometer was held in the patient’s hand or fixed to the wrist. The active electrode was placed at two points on the area of skin innervated by the mental nerve on the affected side, with one point situated midline at the vermilion border of the lower lip and the other situated in the labiodental fold. Neither the equipment nor the operator was in view of the patient. Three measurements were performed with a 10-minute interval, and the results were averaged. The measurements were performed before and after the operation on everyday basis as an in-patient. After discharge, the measurements were performed on every checkup.

Results

Sacrificing the IAN during mandibular resection is standard practice. However, the resulting permanent numbness of the ipsilateral lower lip and chin is debilitating and can be avoided by transposing the IAN out of the mandibular canal. Advances in 3D modeling can make this procedure easier, faster, less traumatic, and yield more predictable results (Figure 9a, b). In this series of 21 cases, we demonstrated a refined approach to preservation of the IAN during mandibular resection.

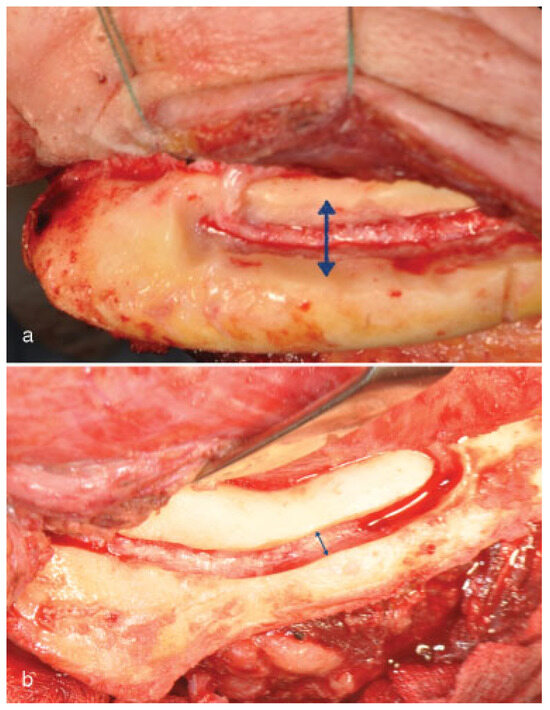

Figure 9.

(a) Approach to the inferior alveolar nerve without a guide. (b) Approach to the inferior alveolar nerve with a guide.

The IAN was preserved unilaterally in 7 patients (33%) and bilaterally in 14 patients (67%). Sensation of the lower lip was preserved in 18 patients (86%). In some cases, patients temporarily lost lower lip sensation due to intraoperative manipulation of the IAN; however, these patients generally recovered sensation within 22 days postoperatively. The failure to preserve the nerve in three cases was due to technical errors. The majority of the patients (82%) in this study suffered from cancer of the oral mucosa. During the follow-up period of 3 to 30 months, there were no incidences of tumor recurrence. To achieve these results in cancer patients, we adhered to the following principles: (1) The tumor should not have spread onto the periodontal ligament or beyond the middle of the alveolar ridge. (2) The tumor should not have spread beyond the insertion point of the mouth floor muscles. (3) There should be no obvious invasion of the tumor into the mandible through the lingual cortical bone.

In designing these criteria, we considered that the mandibular canal has its own cortical bone, which is an additional barrier to the spreading tumor.

Conclusion

Preservation of lower lip sensation in patients undergoing mandibular resection significantly improves their quality of life. VSP, surgical cutting guides, and a guided approach to the mandibular canal can reduce trauma and intraoperative time. Cancer patients should, however, meet strict criteria to be considered for this procedure. An absolute contraindication for IAN preservation is invasion of the tumor into the mandible or tumors occurring within the mandible itself.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

References

- Ziccardi, V.B.; Assael, L.A. Mechanisms of trigeminal nerve injuries. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2001, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abarca, M.; van Steenberghe, D.; Malevez, C.; De Ridder, J.; Jacobs, R. Neurosensory disturbances after immediate loading of implants in the anterior mandible: an initial questionnaire approach followed by a psychophysical assessment. Clin Oral Investig 2006, 10, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, O.; Nock, D. Inferior alveolar nerve repositioning in conjunction with placement of osseointegrated implants: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1987, 63, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahnberg, K.-E.; Ridell, A. Transposition of the mental nerve in orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987, 45, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuriakose, M.A.; Lee, J.J.; DeLacure, M.D. Inferior alveolar nerve- preserving mandibulectomy for nonmalignant lesions. Laryngo- scope 2003, 113, 1269–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vicente, J.C.; López-Arranz, J.S. Preservation of the inferior alveolar nerve in the surgical approach to cancer of the posterior oral cavity. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998, 56, 1214–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the author. The Author(s) 2008.