Oral cavity cancer is rated as the sixth most common cancer worldwide.[

1] The overall survival rates remain low, between 40 and 66%.[

2] In this regard, tumor size and cervical metastasis (CM) at diagnosis are considered as the most important prognostic factors.[

3] Surgery is the treatment of choice for resectable cancers. In addition, a neck dissection is indicated in cases of T2/T3/T4 tumors, tumor thickness of greater than 0.4 cm, or if there is a clinical or radiological suspicion of CM [

4,

5].

Due to this relatively low incidence of buccal mucosa cancers, there are relatively few large-sample studies that analyze this specific location. Many authors routinely cluster all cancers of the oral cavity into a single group without discrimination of the anatomical location. Thus, the main aim of the present report is to analyze the pattern of distribution of CM in buccal mucosa cancer CM and to discuss the various therapeutic options available. A further objective was to analyze the numerous histological features and to evaluate the impact of each factor on overall survival.

Materials and Methods

Between 2003 and 2011, fifty-three previously untreated patients with SCC of the buccal mucosa were diagnosed and treated with at least a tumorectomy and selective neck dissection at Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves. The neck dissections included levels I to III in patients with clinically negative neck. However, the neck was recorded as clinically positive (N+) in any case of suspected clinical or radiological node involvement. In these cases, an elective neck dissection of levels I to V was performed.

The male/female ratio was 1.2:1 (29 males/24 females). Patient ages ranged between 35 and 90 years, with a mean of 60.13 (SD: 9.917). The clinical stage of the primary tumor was determined by using the recommendations of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC).[

13] A careful clinical exploration and a computed tomographic scan of the cervicofacial area were conducted on all patients before surgery. Hence, 43 (81.1%) patients were classified as N0 and 10 (18.86%) patients as N(+) preoperatively. However, node involvement was evidenced in seven (13.2%) of the patients classified as clinically N0. Thus, 17 (32%) patients presented nodal involvement at the postoperative histopathological examination. Fifteen (28.3%) of the primary tumors were T1, 19 (35.6%) were T2, 8 (15.1%) were T3, and 11 (20.8%) were T4 (

Table 1).

It is important to note that adjuvant RT/QT was used in all patients with positive neck dissection and/or poor prognostic factors (T3, T4, ECS, surgical margins, as well as nerve and vascular invasion).

An Apron flap incision was used to guarantee better access to level IV and the posterior triangle (level V). In the case of unilateral neck dissection, a horizontal incision from the mastoid curving inferiorly upward toward the upper border of the thyroid was performed 3 to 4 cm caudal to the mandibular margin. In the case of bilateral neck dissection, the incision is performed from mastoid to mastoid. In our study, neck levels were differentiated according to the classification proposed by the American Head and Neck Society [

14].

A split neck dissection was performed to identify the lymphatic territories most affected by cancer of the buccal mucosa. More specifically, the surgical team identified, labeled, and separated the operation specimens in the surgical field before immersion in formalin. The specimens were examined and dissected by a single pathologist.

Several pathological features such as T stage, N stage, tumor thickness, ECS, and vascular invasion were also analyzed. Tumor thicknesses were divided into two groups, less than 0.4 cm and greater than 0.4 cm. At the time of analysis, all surviving patients had at least 5-year follow-up.

Statistical analysis wasconductedusing SPSS 23v. Frequency and percentages were used to evaluate the pattern of distribution of cervical metastases. A correlation test was performed to analyze the relationship between variables. A Chi-square test was conducted to compare the differences between N0 and N+ patients. Specificcontingency tables allowed for the calculation of the impact ofeach factor on patient survival. The p-value was set at 0.05. Finally, a Kaplan–Meier test was performed to obtain an overall 5-year survival analysis.

Results

In our sample, 17 of 53 patients presented node involvement after histological examination (32%), 1 of these 17 tumors (5.8%) being T1, 3 (17.6%) T2, 5 (29.4%) T3, and 8 (47.5%) were T4 (

Table 1). Thirty-six (68%) patients were classified as N0, 6 (11.3%) as N1, and 11 (20.8%) as N2. Fifty-nine cervical nodes were infiltrated by malignant cells. Level Ib was the most affected level, with 35 (59.3%) metastases found at this level. Eighteen (30.5%) positive nodes were identified at level IIa and 6 (10.1%) were found at level III. Interestingly, no metastases were found at levels IIb, IV, and V.

With respect to pathological features, our findings indicate that T stage and tumor thickness of greater than 0.4 cm are directly related to node involvement (

p < 0.01;

Table 1). Smaller tumors were significantly more frequent in the N0 group, with 14 T1 tumors being diagnosed in this group. However, only one T1 tumor was evident in the N+ group. In contrast, T4 tumors were more common in the group of patients with nodal involvement. Of the 11 T4 tumors observed, 8 of the affected patients belonged to the N+ group. Major T stages were associated with worse outcomes in terms of cervical affectation, surgical margins, and greater tumor thickness (

p < 0.01). Similarly, tumors with a depth of invasion less than 0.4 cm were more frequent in the group of patients with N0 (

p < 0.01). Specifically, 26 of the 36 (72.2%) tumors found in group N0 patients presented a tumor thickness of less than 0.4 cm. However, no tumors from the group of N+ patients showed a tumor thickness of less than 0.4 cm (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

With respect to relapse rate, 36 patients experienced a local or cervical recurrence (67.9%). Specifically, 16 of the patients (30.1%) in our sample suffered a cervical relapse. Local failure was observed in 20 (37.7%) patients. According to our findings, relapse rate is significantly related to T, N, and tumor thickness (p < 0.01). Fourteen of 16 cervical recurrences (87.5%) occurred in T3/T4 tumors. However, only 1 patient (6.6%) of the T1 group (n = 15) presented a cervical recurrence during follow-up. In the same vein, 15 of the 20 local failures (75%) were observed in T1/T2 tumors (4 in T1 tumors and 11 in T2 tumors).

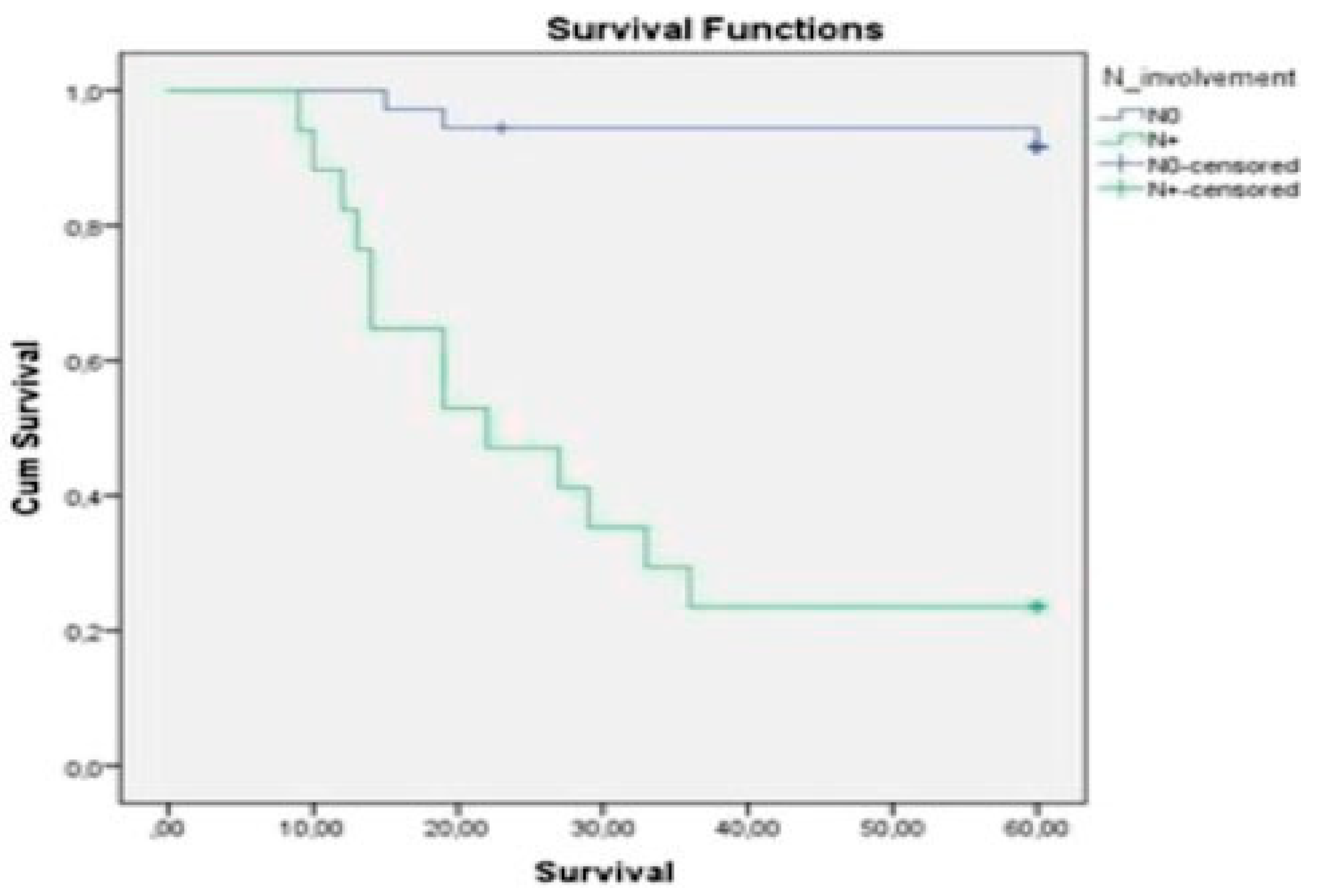

T stage (

p < 0.01;

Figure 1), depth of invasion (

p < 0.01), node involvement (

Figure 2), ECS (

p < 0.01;

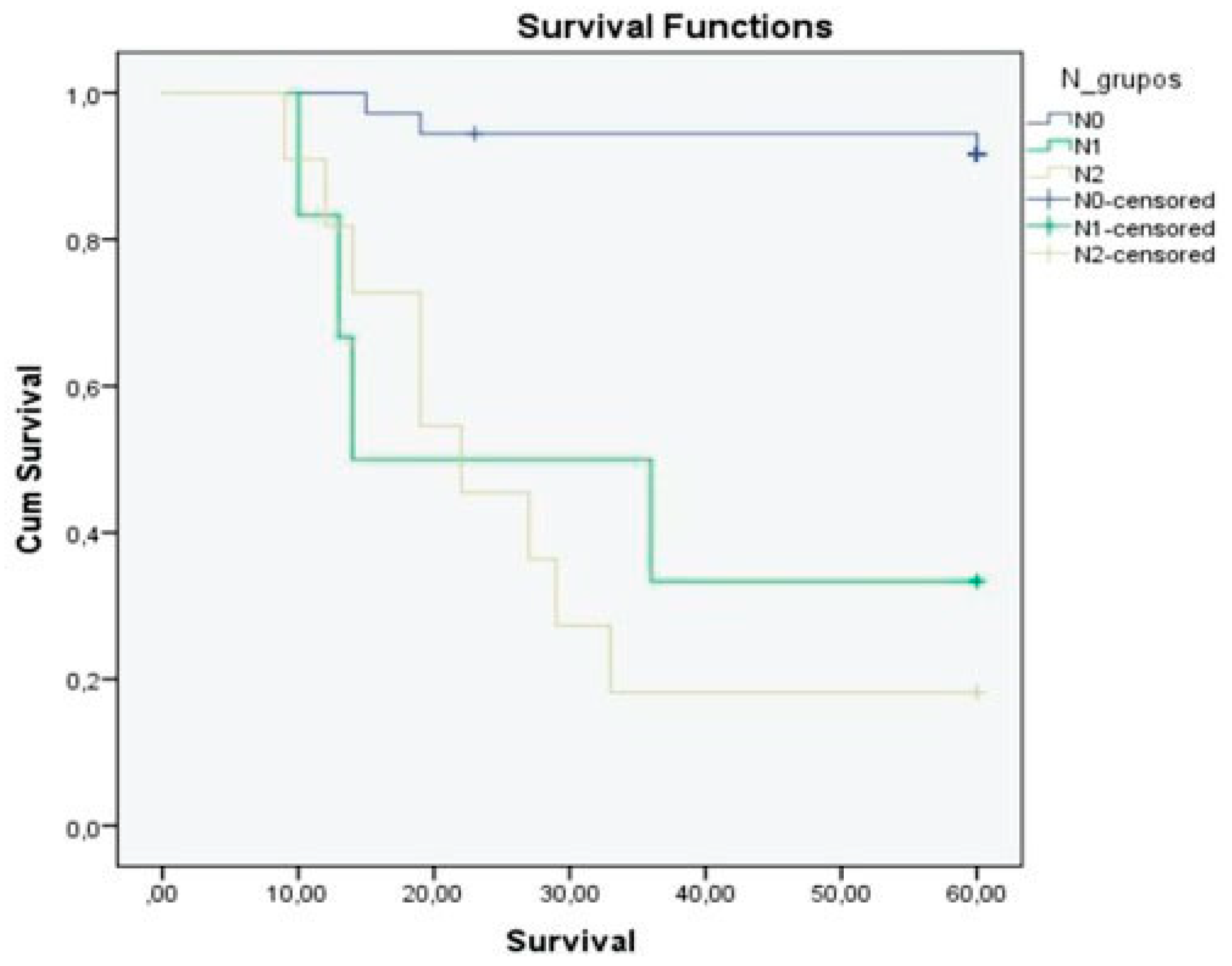

Figure 3), N stage (

p < 0.01;

Figure 4), and nerve and vascular invasion (

p < 0.01) were significantly related to 5-year overall survival (

Table 3). The 5-year overall survival rate was 69.8%. N0 patients showed better outcomes, with the 5-year overall survival being 91.7% in this group and 23.5% in N+ patients. We observed a 5-year overall survival rate of 33.3% for the N1 patients and 18.2% for the N2 group (

Figure 4,

Table 3).

Discussion

The behavior of buccal mucosa cancer is not completely defined. Due to the low incidence of this disease, relatively few studies have specifically analyzed this type of cancer.[

11] In our sample, the node involvement rate was 32%. The 5-year overall survival rate was 69.8%, which appears to be strongly related to N stage, node involvement, T stage, tumor thickness, extracapsular spreads, and vascular infiltration. These results are comparable with the results of other studies in the field. For instance, Diaz et al. studied 119 previously untreated patients with cancer of the buccal mucosa. They found a node involvement rate of 27.7%, and a 5-year overall survival of 63% that appeared to be significantly associated with N stage, node involvement, and extracapsular spread. However, T stage was not significantly associated with overall survival in this series.[

11] The smaller number of T3 and T4 tumors observed in our sample (35.9 vs. 64.2%) could explain our better outcomes in terms of overall survival. Similarly, Vegers et al. analyzed the behavior of 85 SCC of the buccal mucosa, finding an overall survival rate of 55%. In their study, the rate of CM was 59% (

n = 38).[

15] Interestingly, 61% (

n = 39) of the patients presented a T3 stage tumor.[

11] In contrast, Sagheb et al. reported a node involvement rate of 24% with an overall survival rate of 80% in a series of 113 buccal mucosa cancers.[

16] Importantly, 79% of the patients included in this study presented a T1/T2 tumor. Moreover, Dhawan et al. reported a node involvement rate of 16% in a series of 57 cancers of the buccal mucosa [

17].

Thus, there appears to be an absence of unequivocal and clear data on the behavior of this type of carcinoma. With respect to the distribution of CM in buccal mucosa cancers, level Ib was the most affected lymphatic region in our study, followed by level IIa. Specifically, 59.3% of all cervical metastases identified at postoperative pathological examination occurred at level Ib, and 30.5% were found at level IIa. Level III was involved in 10.1% of the cases. These data differ substantially from the outcomes observed by Dhawan et al. In fact, according to these authors, level I and level II patients are affected with almost the same frequency.[

17] Interestingly, no instances of metastasis or cervical recurrence were found at level IV or level V in our sample. Similarly, Hasegawa et al. evidenced only one metastasis at level IV or V in a series of 38 patients analyzed with this specific cancer (4.3%) [

18].

With respect to local relapse, there are mixed findings in the current literature. In particular, the incidence of local failure for cancer of the buccal mucosa varies from 29 to 100%. For instance, Lin et al. reported a local recurrence incidence of 57% in a series of 121 SCCs of the buccal mucosa,[

19] and Sieczka et al. revealed a local recurrence rate of 56% for patients treated only with surgery.[

20] Strome et al. reported a tumor recurrence rate of 80%, and Fang et al. reported a locoregional failure rate of 39%.[

21,

22] Our relapse rate was 67.9% (36 patients). Sixteen of our 53 patients (30.1%) developed a cervical relapse and 20 (37.7%) had a local recurrence. Our outcomes in terms of local recurrence are therefore comparable with outcomes of other studies. In this regard, Diaz et al. reported a local recurrence of 45%.[

11] The precise reasons for this high rate of locoregional failure are still unclear, although there are several possible accounts that could explain this aggressive behavior. For instance, the absence of a clear anatomical barrier in the buccal mucosa might play an important role, and its relative proximity with the buccal fat could facilitate rapid spreading of the tumor. The buccinator muscle and its overlying fascia represent the only obstacle to the spread of malignant cells. Inadequate treatment and the intrinsically aggressive nature of the tumor have also been proposed to explain this phenomenon.[

11] Thus, several authors advised aggressive treatment of this cancer from the early stages. For instance, Trivedi et al. advised to perform a compartmental surgery to improve the overall survival.[

23,

24] In this sense, Sieczka et al. affirmed that low T stage and negative margins do not represent adequate predictors of local control and adjuvant therapy may be extremely useful to enhance local control even at early stages.[

20] Lin et al. reported that postoperative radiotherapy improves the locoregional control rate for patients with T3–4 or N+ disease and should also be considered for patients with T1–2N0 stage.[

19] Sagheb et al. recommended performing a supraomohyoid neck nodes dissection even at the early stage of buccal mucosa carcinomas.[

16] Moreover, Diaz et al. confirmed that elective treatment of the neck reduces the regional recurrence rate from 25 to 10% in N0 patients. These authors recommended performing an elective supraomohyoid neck dissection in lesions with tumor thickness of ≥0.3 cm or if there is evidence of lymphatic invasion of the primary tumor.[

11] In our study, tumor thickness also proved to be a very important factor in predicting the behavior of cancers of the buccal mucosa. In particular, the depth of invasion was strongly related to numerous prognostic factors such as T, N involvement, N stage, extracapsular spread, vascular invasion, local recurrence, cervical recurrence, and overall survival. In our series, no patient with a tumor thickness of ≤0.4 cm presented node involvement at post-operative histopathologic examination. However, 50% of patients (13 of 26 patients) with a depth of invasion ≤0.4 cm experienced a local recurrence. Importantly, no cervical recurrences were evidenced at follow-up in the group of patients with tumor thickness of ≤0.4 cm. In contrast, the rates of local and cervical failure were 25.9% (7 of 27 patients) and 59.2% (16 of 27 patients) in patients with a tumor thickness of greater than 0.4 cm. With regard to T stage, 80% of T1 tumors presented a tumor thickness of ≤0.4 cm. In contrast, none of the T3/4 tumors showed a depth of invasion ≤0.4.

Several authors have also indicated that T stage is an important prognostic factor in buccal mucosa cancer. Lin et al. showed that Tstage is significantly related to locoregional failure and overall survival.[

19] Indeed, according to Fang et al., locoregional failure would represent the major cause of death for this type of cancers.[

22] In our series, only 1 of 17 N+ patients presented a T1 tumor (5.8%). However, 62.5% of T3 and 72.7% of T4 tumors showed node involvement at postoperative histopathological examination. According to our outcomes, T stage appeared to be strongly related to several prognostic factors such as N stage, N involvement, tumor thickness, locoregional failure, extracapsular spread, vascular invasion, and overall survival. Interestingly, 5 of the 15 patients with T1 tumors (33.3%) experienced a local (4/15) or cervical (1/15) recurrence at follow-up. These data support theories that consider cancer of the buccal mucosa as an aggressive pathology from the early stages.[

11,

16,

19] Thus, we recommend carrying out a supraomohyoid neck dissection even in cT1N0 if there is a suspicion that the tumor thickness may be greater than 0.4 cm. The high risk of local recurrence necessitates protection of the neck from future cervical recurrence even in a T1 tumor. This could reduce the risk of cervical involvement during at follow-up and improve overall survival.[

11] In addition, postoperative radiation therapy should be used if there is more than one lymph node involved, evidence of extracapsular spread, or close surgical margins.

To summarize, this report highlights three central points. First, SCC of the buccal mucosa should be considered as a highly aggressive pathology from the early stages. Thus, we recommend performing a supraomohyoid neck nodes dissection even in the case of a T1 tumor if there is a suspicion that the depth of tumor invasion may be greater than 0.4 cm. This could be helpful for improving overall survival. Second, the lack of an anatomical barrier in the buccal region facilitates a rapid spreading of the tumor. Hence, a large tumorectomy of the primary tumor is required to reduce the number of local recurrences at follow-up. Third, several histopathological features such as tumor thickness, N involvement, N stage, T stage, extracapsular spreads, and vascular invasion represent poor prognostic factors in oral cancers of the buccal mucosa as well as in other oral cancers.