Mucocele is a benign, expansile cystic mass covered by respiratory epithelium, resulting from the accumulation and retention of secretion, desquamation, and inflammation in cases where the drainage is obstructed[.[

1] It is most commonly seen in frontal and ethmoidal sinuses, and rarely seen in maxillary and sphenoidal sinuses. It can erode the surrounding bone and spread intraorbitally and intracranially. Patients commonly present with pain, nasal congestion, diplopia, and exophthalmos depending on the location of the lesion and the extent of bone erosion.[

2,

3] We report an unusual case of posttraumatic glabellar mucocele with subcutaneous extension and nasal bone erosion without any neurologic or ophthalmologic involvement.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man presented to the outpatient clinic of the Craniomaxillofacial Surgery Unit of the University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy, with a 10-year history of a slow-growing swelling over the glabellar area. The onset of the swelling was insidious and gradually increasing in size. It was not associated with pain, fever, headache, drainage, nasal discharge, bleeding from the nose, or alteration in the sense of smell or taste. The only symptom was nasal obstruction. There was a history of craniofacial trauma that had occurred in 1992, and was treated in another center. The patient had no infection and had not undergone any recent surgery.

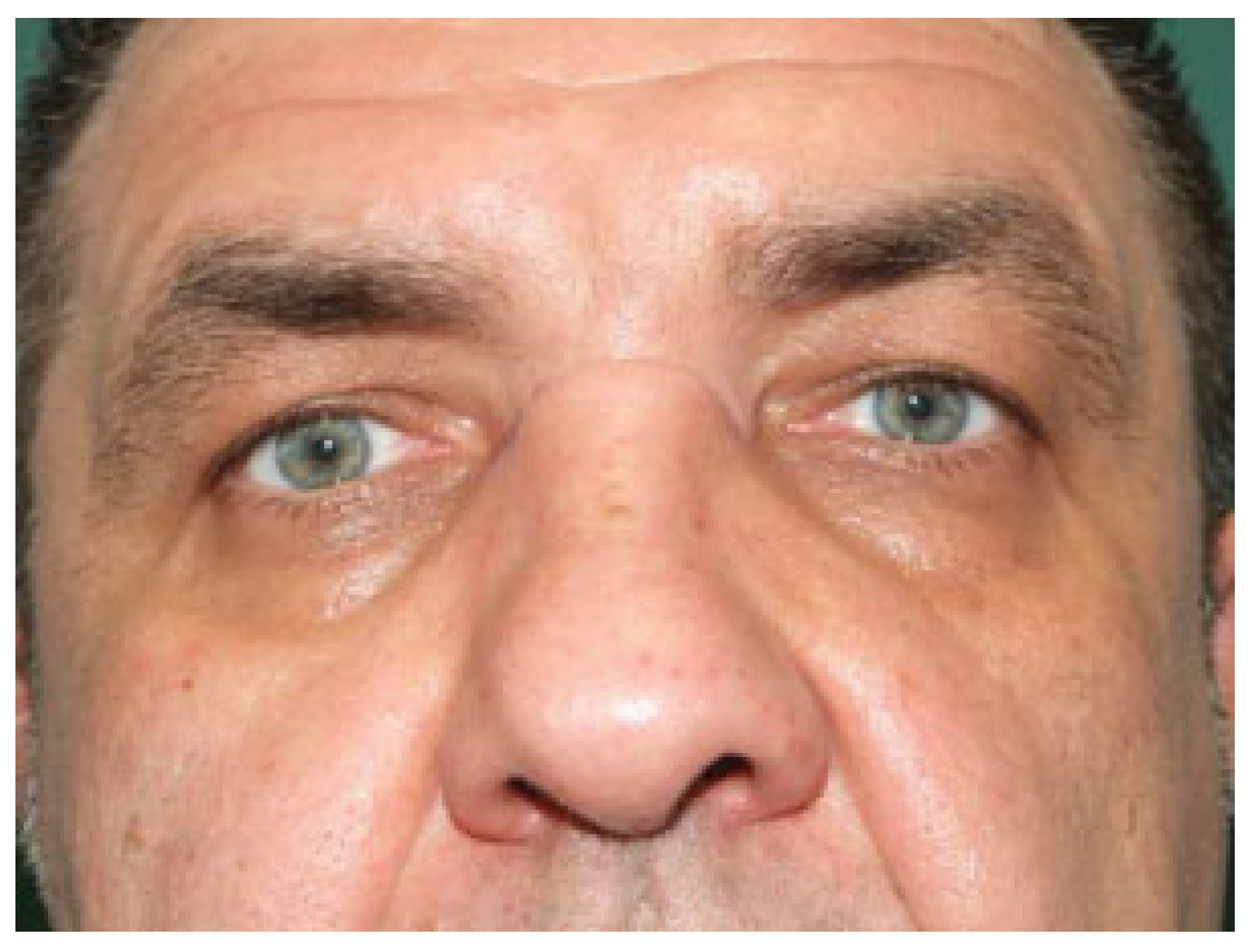

On physical examination, there was a bulge in the area between the eyebrows, over the nasal bones, measuring approximately 35 × 20 mm; the skin over the swelling appeared normal and did not adhere to the mass (

Figure 1). The neoformation showed a subcutaneous mass of relatively soft consistency, which on palpation was nontender and moderately mobile. No local rise in temperature was observed. Anterior rhinoscopy showed inferior turbinate hypertrophy and septal deviation.

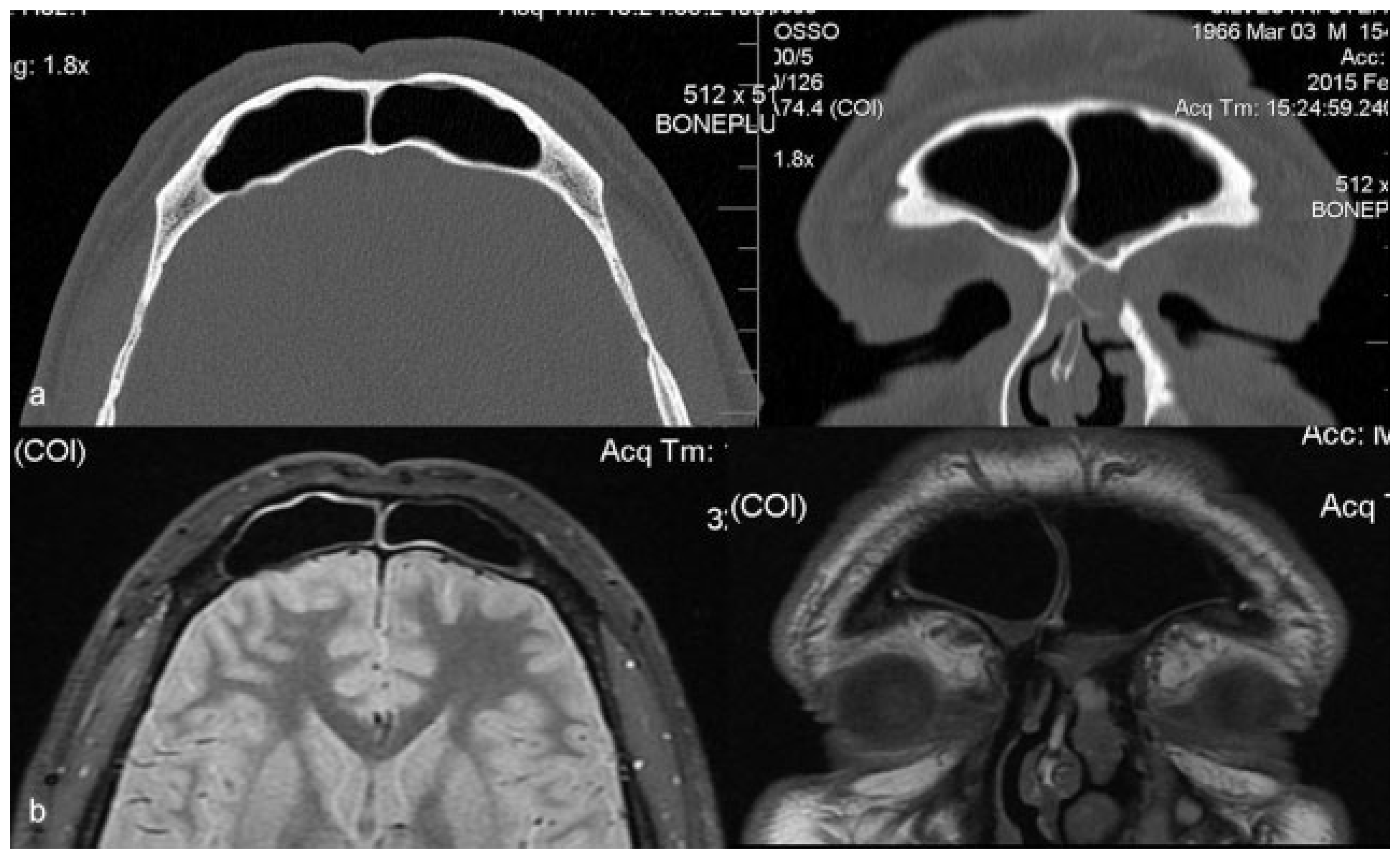

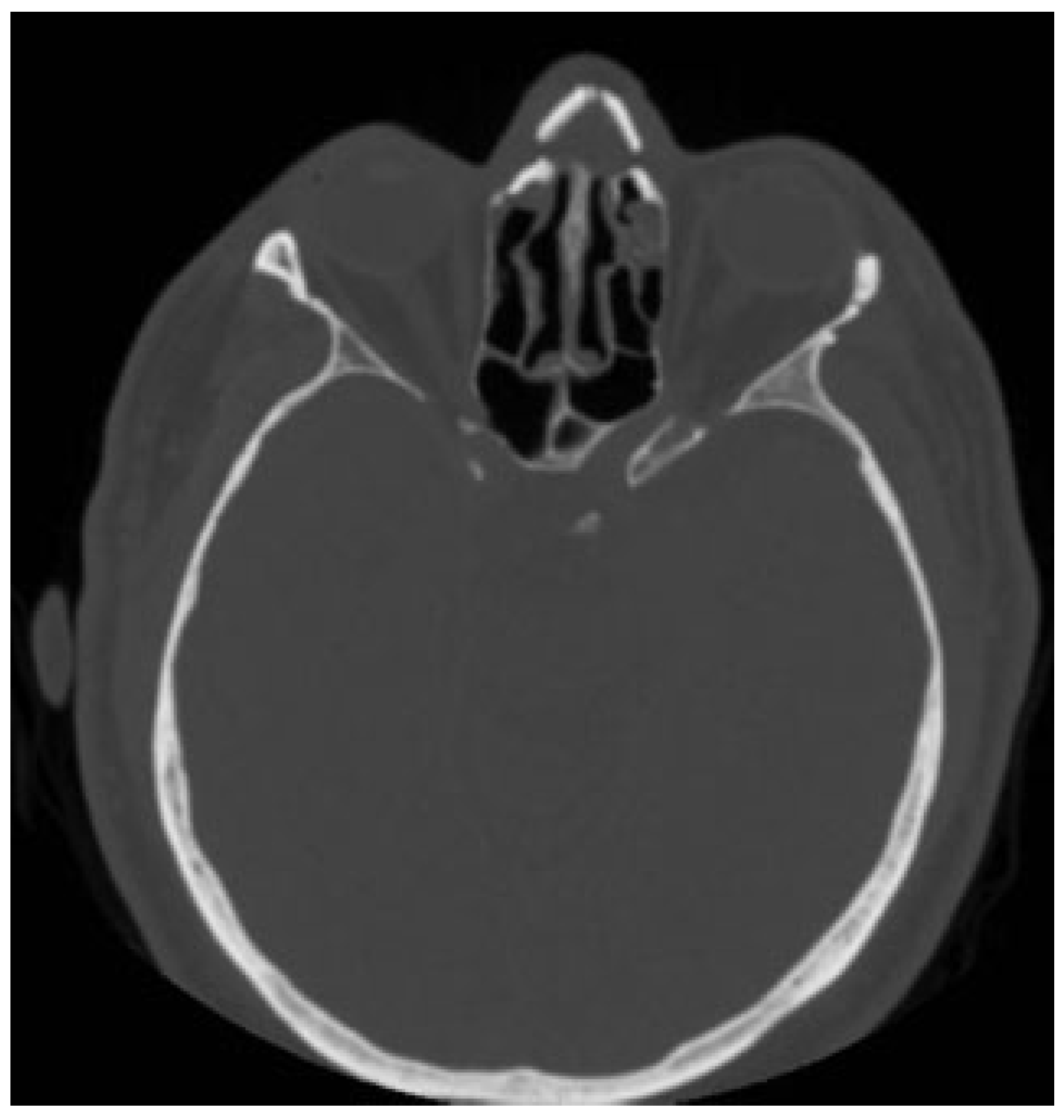

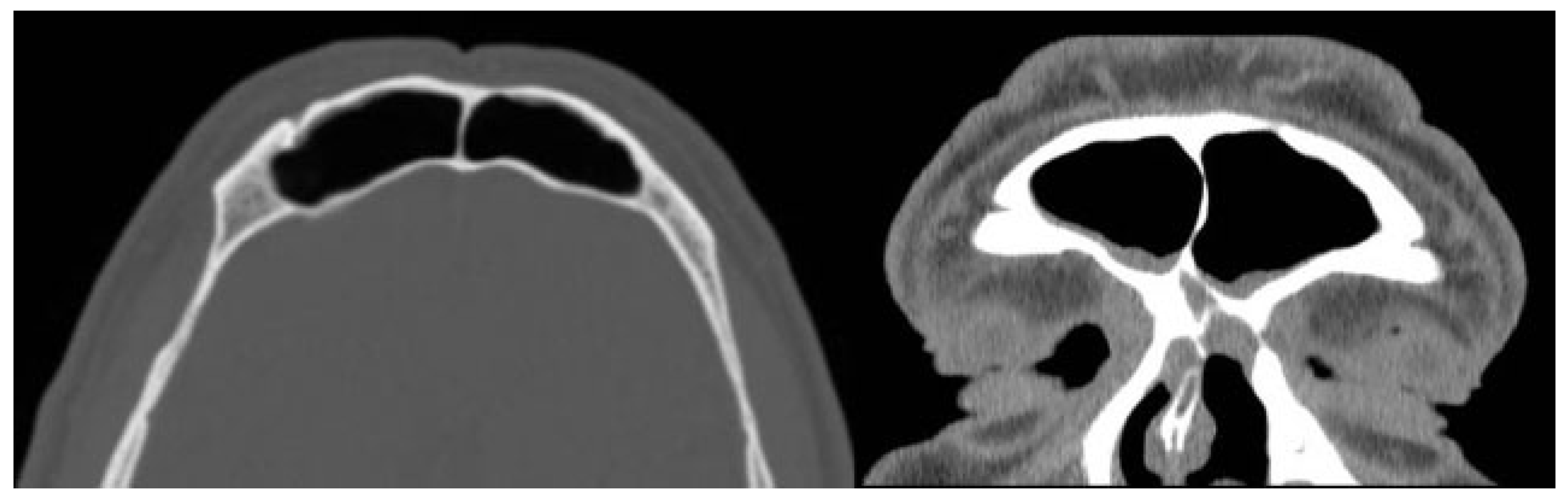

Computed tomography (CT) revealed a wide loss of substance in the root of the nose and a cystic neoformation involving the nasal bones (

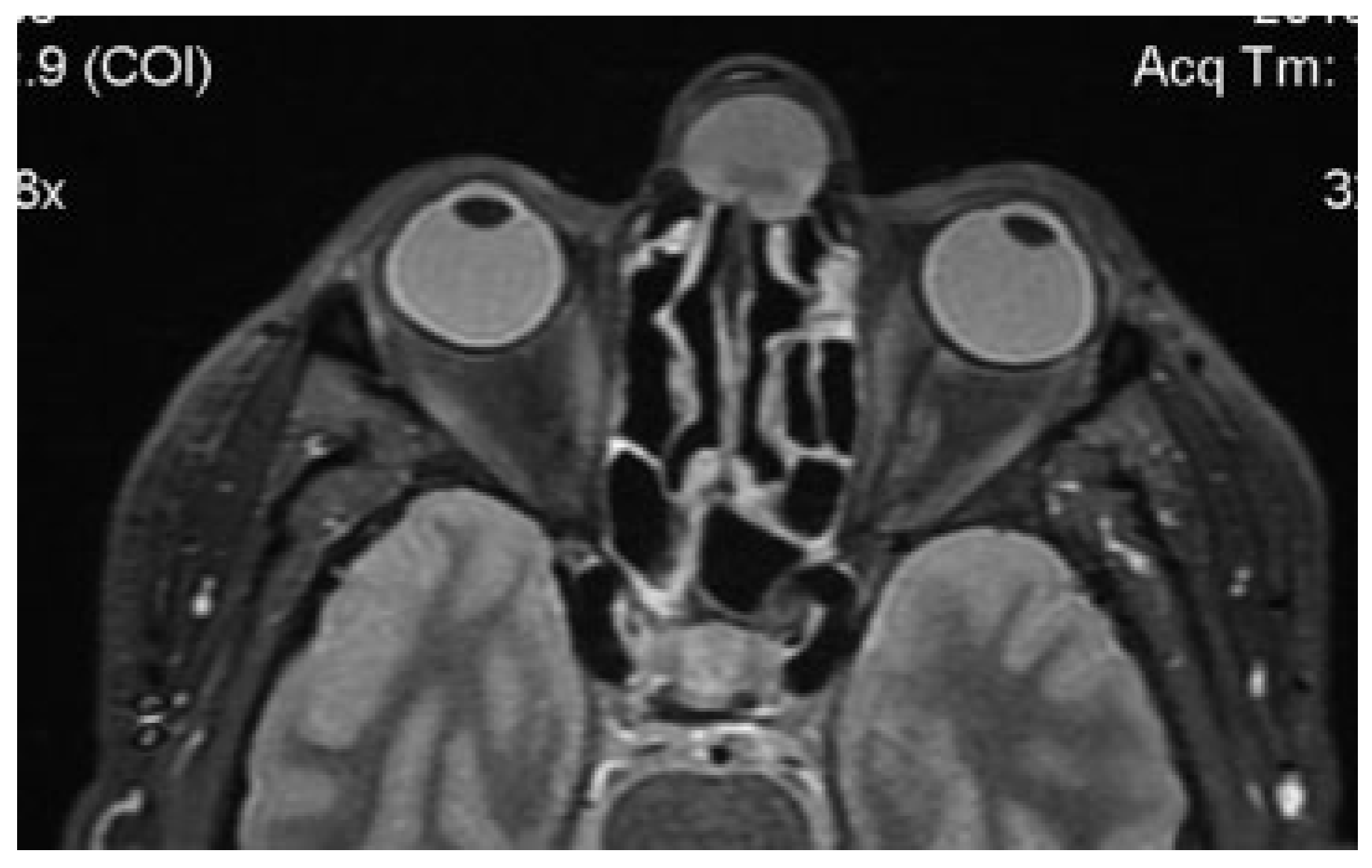

Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a globular cystic lesion with a fluid content occupying the upper region of the root of the nose and partially protruding into the nasal cavity (

Figure 3). CT scan and MRI showed no involvement of the frontal sinus and frontal recess (

Figure 4).

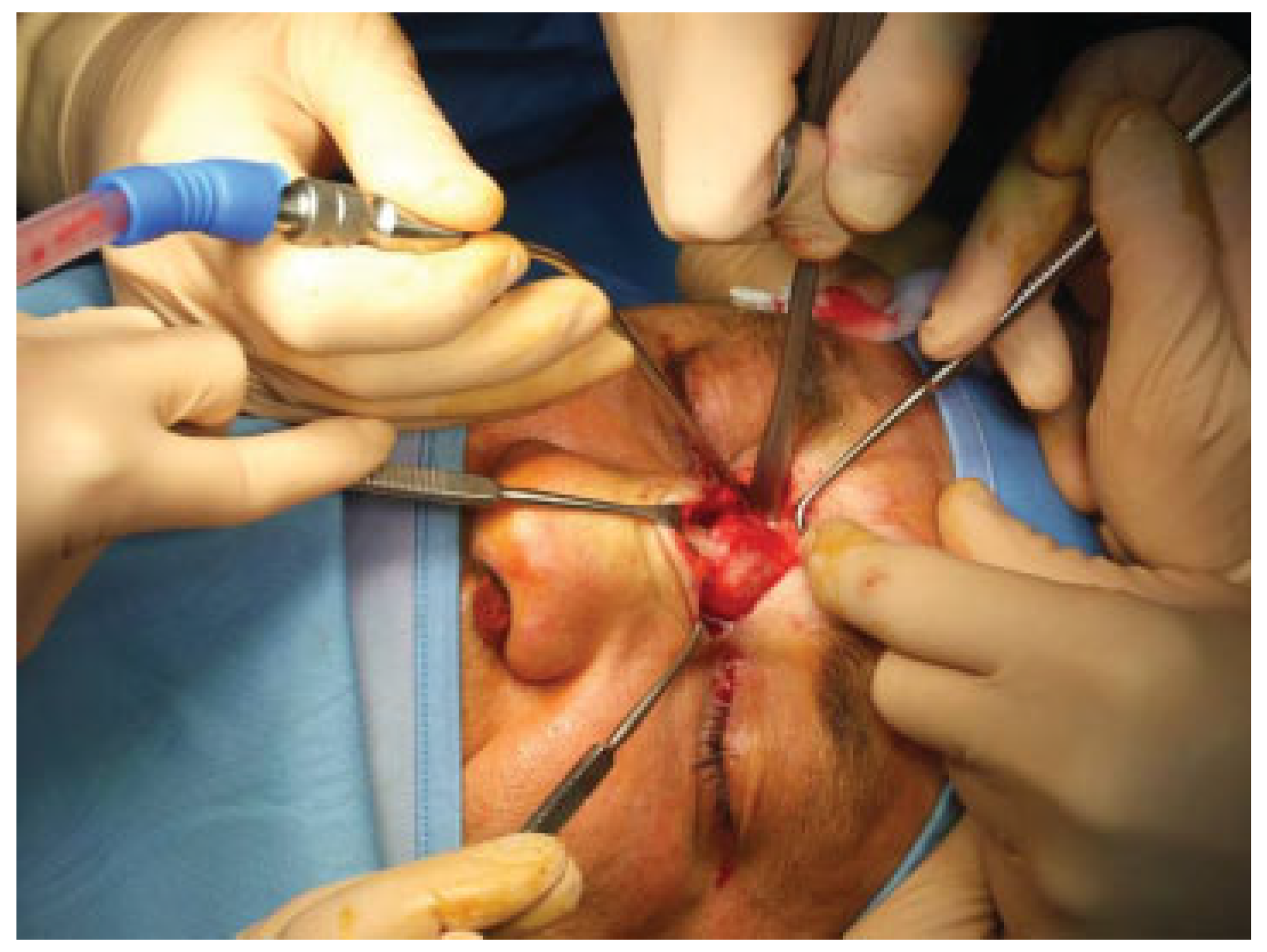

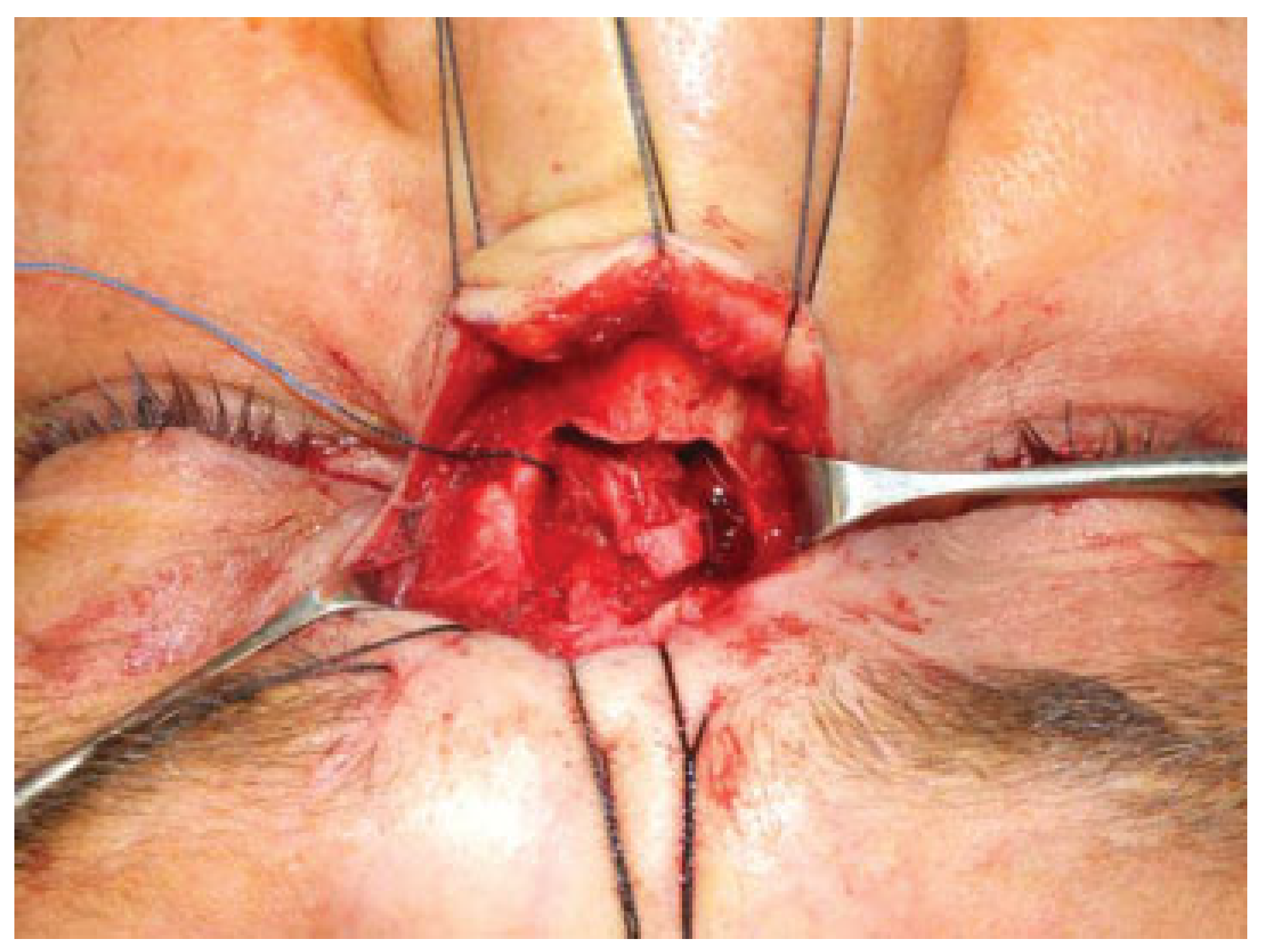

A surgical correction was planned and performed in conjunction with the otolaryngologist. The operation started under general anesthesia. A glabellar approach through an incision performed in the glabellar furrow was used to access the mass. It was a well-demarcated, globular, fluid-containing cystic structure adherent to the nasal bones and nasal mucosa. The mass was well isolated and completely excised and the affected mucosa was removed (

Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7). On histological examination, the cyst was lined with respiratory epithelium containing numerous mucin glands.

As there was erosion of the nasal bones, the recess was plugged with a pericranial fragment measuring 5 × 7 cm and the osseous defect was repaired by a split calvarial bone graft harvested from the temporal region. Bone fragments were fixed with micro-/miniplates to gain rigid support. The otolaryngologist performed a septoturbinoplasty. An intranasal packing type “Ivalon” (Anatomical Nasal Packing, FABCO) covered with gentamycin sulfate cream and moisturized with tranexamic acid solution was left in place for 48 hours.

The recovery was uneventful. A 2-month postoperative CT scan showed good reconstruction of the nose and the glabellar area and frontal sinus patency with a minimal mucosal thickening of the frontoethmoidal recess (

Figure 8 and Figure 9). No late complications occurred, appearance of the face returned to normal, and the results were stable at 12-month follow-up with the patient’s full satisfaction with his facial appearance (

Figure 10).

Discussion

Mucoceles are slow-growing, cystic, and benign lesions. The cyst wall is lined by cubic or pseudostratified epithelium. Mucoceles are thought to occur due to obliteration of the sinus ostium because of inflammation, allergic reactions, tumors, trauma, or surgery.[

2]

Posttraumatic mucoceles are rare. They can occur when fractures result in mucosal entrapment and subsequent cyst formation.[

4] This complication can appear several years after the original injury[

5] and the symptoms may go unnoticed for a long period of time.[

6,

7] Koudstaal et al[

6] found three cases that occurred with a spread of incidence between 1 and 35 years after trauma. Mourouzis et al[

8] have reported cases up to 50 years later on. This suggests that not only a long-term follow-up period should be considered after injury but that a conscientious anamnesis should also be performed in suspicious cases.[

5] Despite their benign character, nasal mucoceles have the ability to destroy the adjacent bony structures. Gradual distension, thinning, and the eventual erosion of the bony structures in the direction of least resistance are caused by progressive accumulation of mucoid material.[

9]

Symptoms may vary according to the lesion location, size of the bone defect, and compression, such as pain and nasal congestion, eye swelling, diplopia, loss of visual acuity, and intracranial complications in a spectrum from mild to severe.[

2]

Radiographically, CT scans provide basic anatomical detail of the mucocele, delineate its interaction with neighboring bony structures, and aid in surgical planning. CT scan findings show an expansile, homogenous sinus mass that is not rim enhancing, unless associated with an acute mucopyelocele. Bony destruction is not common but expansion and remodeling of bone is seen in association with the mucocele. MRI is superior in identifying the relationship of the mucocele to neighboring soft tissue and in distinguishing from other soft-tissue neoplasms.[

10] Mucoceles may show different forms on MRI due to the water–protein content. They may be hyperintense in T2 images due to the high water content, while those with high protein content may be isointense or hyperintense.[

2]

The definitive treatment for nasal mucoceles is surgical excision. Many surgical approaches have been proposed depending on the topography of the lesion: open rhinoplasty approach, intranasal approach, direct external cutaneous approach, and endoscopic excision. The location, magnitude, and expansion of the lesion are determinants of the appropriate surgical procedure.[

11] Regardless of the approach employed, complete excision of the nasal mucous cyst capsule is necessary to prevent relapse of disease. In the present case, a sturdy and durable closure of the bony defect was achieved by an autologous pericranial graft and a bone graft. We used a split calvarial bone graft harvested from the temporal region. Bone fragments were fixed with micro-/ miniplates to gain rigid support. In bone reconstructions, titanium miniplates can be used safely in adults, but resorbable devices are required in children because of growing tissues.[

12] The glabellar region is one of the first areas of the face to reveal early aging in the form of rhytids.[

13] The incorporation of naturally occurring skin wrinkles or relaxed skin tension lines into planned incisions can minimize the appearance of the postoperative scar.[

14]

Conclusion

Treatment for mucoceles eroding the surrounding bone tissue and causing clinical symptoms due to compression by the expansile mass is surgical excision. The location, magnitude, and expansion of the lesion are determinants of the appropriate surgical procedure. In this case, we applied the principles of craniofacial reconstruction, achieving a sturdy and durable closure of the bony defect by autologous pericranial graft and bone graft. Incorporation of preexisting rhytids into the operative plan allowed an aesthetically good result.