Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dislocation is described as displacement of the head of condyles from its normal position in the glenoid fossa [

1]. Several morphological variants exist based on the position of condyles to articular eminence, such as anterior, posterior, medial, and lateral [

2,

3]. However, the anterior subtype is the most common [

4].

Bilateral TMJ dislocation is more frequent than unilateral. Unilateral TMJ dislocation is commonly associated with jaw deviation to opposite side. The majority of cases are non-traumatic and often precipitated after yawning, eating, endoscopy, intubation, and dental work requiring prolonged wide opening of the mouth [

5].

Severe disorders of central nervous system such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, posttraumatic cerebral palsy, and orofacial dystonia are frequently associated with TMJ dislocation [

6]. These patients suffer recurrent episodes of TMJ dislocations due to an excess of muscle contraction spasticity in the muscles depressing the lower jaw [

6]. Some syndromes are also associated with TMJ dislocation such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and Marfan’s syndrome [

7,

8].

Certain medications with antidopaminergic effect such as antipsychotics and metoclopramide may also lead to TMJ dislocation [

9]. These drugs cause oromandibular dystonia which in severe form can cause TMJ dislocation. Antipsychotic drugs such as haloperidol, risperidone, and amisulpride have been reported in the literature to cause TMJ dislocation [

9,

10].

In acute TMJ dislocation, manual reduction with or without pharmacological assistance is the treatment of choice and should be performed as early as possible [

11]. Pharmacological assistance with muscle relaxants such as baclofen and diazepam is mostly needed when there is a secondary reflex spasm of both lateral pterygoid and masseter muscles [

11]. This reflex is followed by painful stimuli from joint space, thus making the reduction procedure more difficult.

Manual reduction can be done under local anesthesia by giving auriculotemporal nerve block or local infiltration in the joint space [

12,

13]. Sedations such as midazolam and diazepam are also routinely used but, when given intravenously, require cardiorespiratory monitoring of the patients [

13]. Muscle relaxants have been utilized in difficult reduction [

13]. Despite the success of manual reduction, there remain a proportion of patients who require reduction under general anesthesia.

On rare situations, TMJ dislocation remains undiagnosed or misdiagnosed for a long period. This may include severe illness, neurological diseases, tetanus infection, and prolonged intensive care hospitalization with oral intubation and sedation. This condition can be easily overlooked especially by clinicians who are unfamiliar to this pathology [

14].

When presented late, closed reduction is difficult. Morphological changes of the joint and associated structures will prevent successful reduction [

11]. Spasm of the masticatory muscles, progressive fibrosis, and adhesions and consolidation in and around the dislocated joint make this reduction challenging and difficult [

12]. Thus, surgical approach is usually warranted. Numerous surgical procedures have been discussed in the literature. Basically it involves elimination of articular eminence (eminectomy) or reestablishment of a new condyle–ramus relationship (condilotomy) [

11,

12].

We present a case of delayed management of TMJ dislocation and its subsequent challenges we faced in the reduction of TMJ dislocation.

Case Presentation

A 24-year-old man was referred to our department for the management of inability to close his mouth. He was involved in a motor vehicle accident (MVA) 5 months prior his referral. He sustained intracranial bleeding with diffuse axonal injury. He was bedridden since the MVA. He has weakness over all four limbs and limited speech.

He had undergone endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy procedure, and Ryle’s tube and percutaneous endoscopic gastrotomy (PEG) tube insertion following the MVA. He started to develop seizures 1 week postdischarged, and 3 months later his parents discovered that he was unable to close his mouth when they tried to feed him orally.

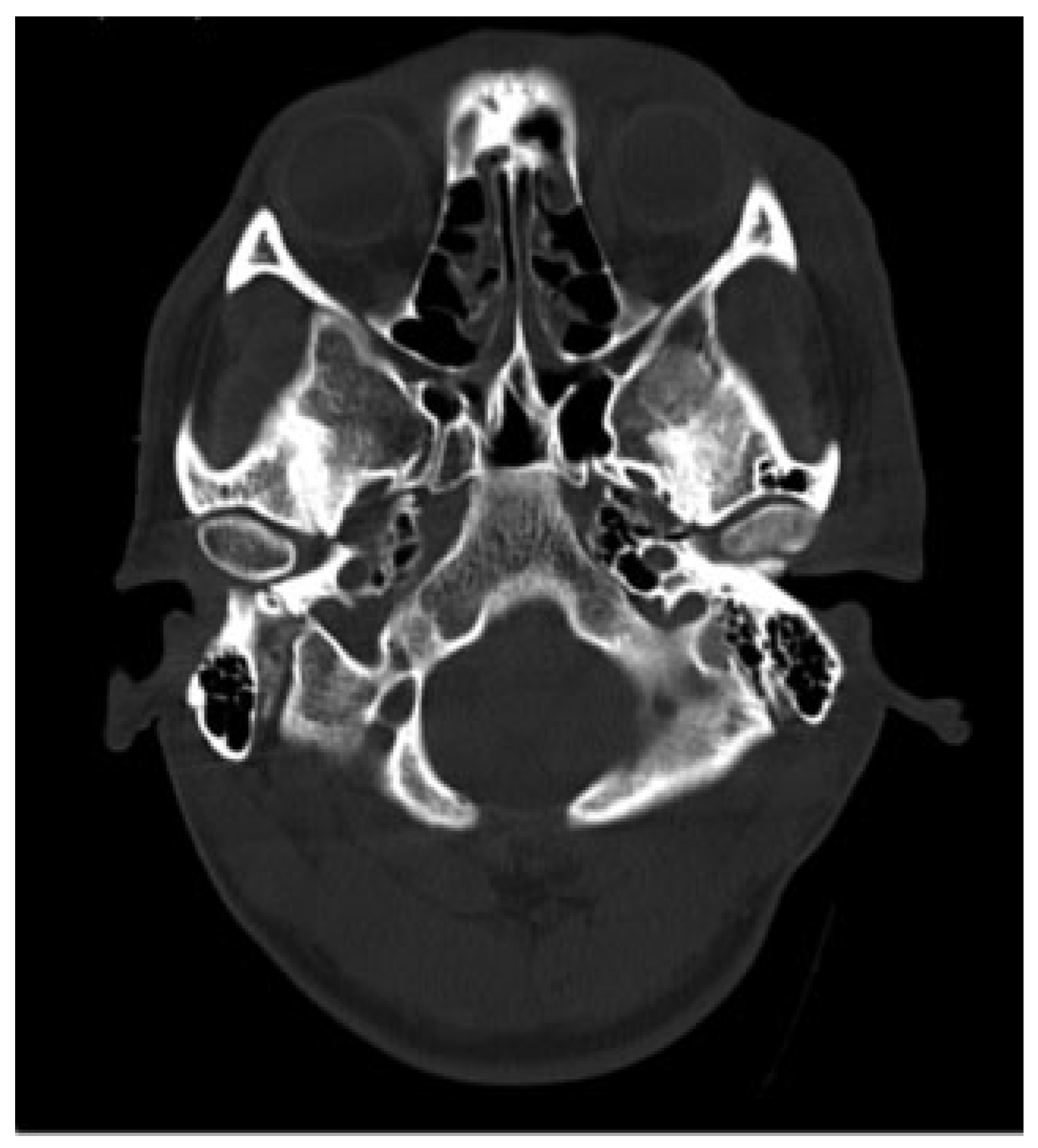

Examination revealed maximum mouth opening was 42 mm with 15 mm of anterior open bite upon closing. Computed tomographic (CT) scan that was taken immediately post-MVA shows no fractures to his facial skeleton and both condylar heads were located in the glenoid fossae ([

Figure 1]). He was subsequently sent for another CT scan to view the position of the condyles. Both condylar heads of the mandible were anteriorly dislocated from the TMJ fossae and were located at bilateral infratemporal fossae ([

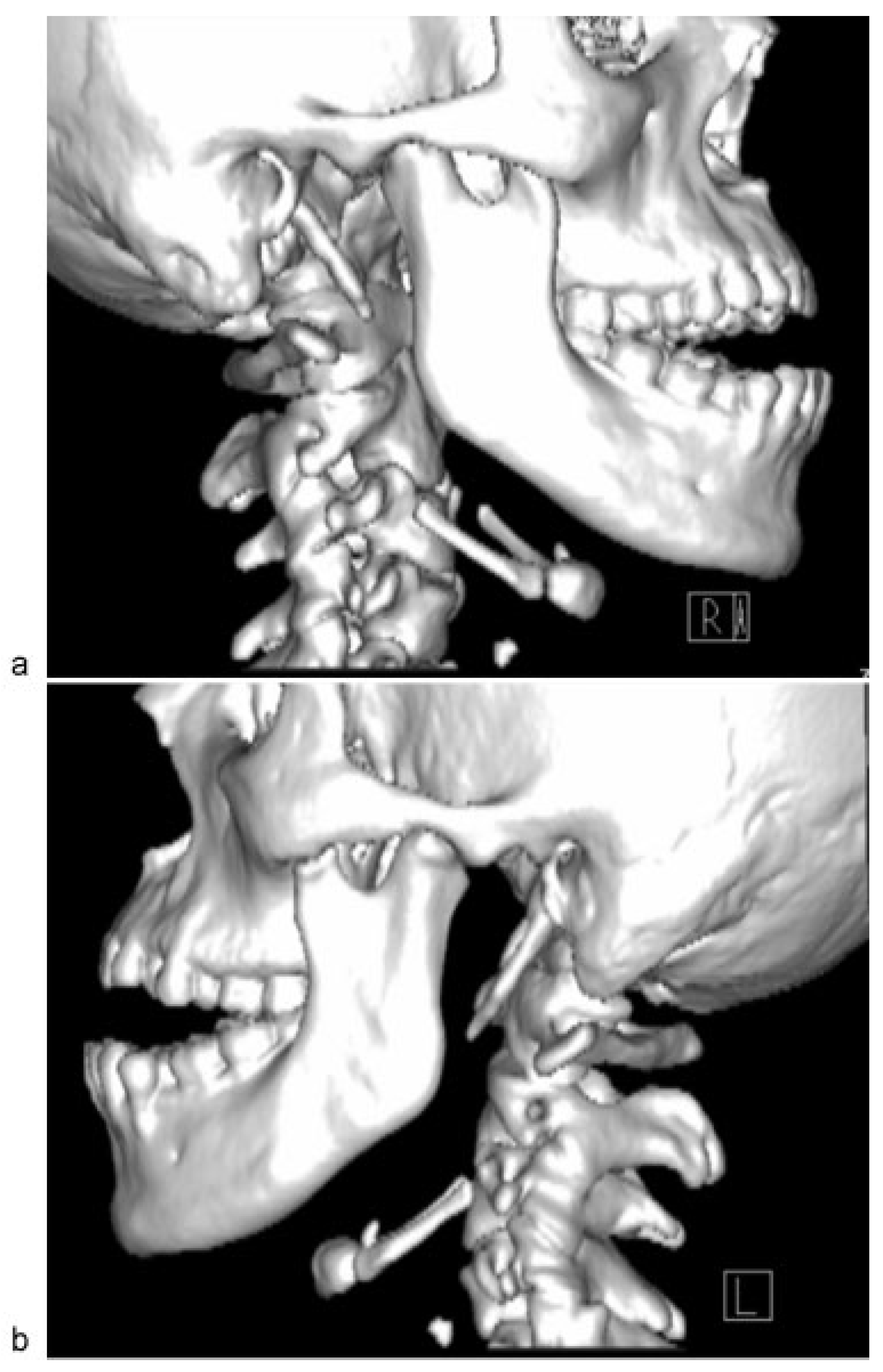

Figure 2]). Closed reduction of the TMJ was attempted for a few times; however, it was unsuccessful because of the stiffness of muscle of mastication.

Closed reduction was attempted again under general anesthesia and deep sedation; however, it was unsuccessful. Thus, the reduction was done surgically.

Figure 1.

Computed tomographic scan immediately post–motor vehicle accident shows both condylar heads located in the glenoid fossa.

Figure 1.

Computed tomographic scan immediately post–motor vehicle accident shows both condylar heads located in the glenoid fossa.

Figure 2.

Dislocations of right and left condylar heads into infratemporal fossa.

Figure 2.

Dislocations of right and left condylar heads into infratemporal fossa.

Bicoronal incision with preauricular extensions bilaterally was performed for better surgical access and visualization. Dissection was carried out to the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia. This fascia was incised with an anterosuperior oblique extension to minimize trauma to the temporal branch of facial nerve. The periosteum on the zygomatic arch was incised, and dissection was performed to the level of articular eminence.

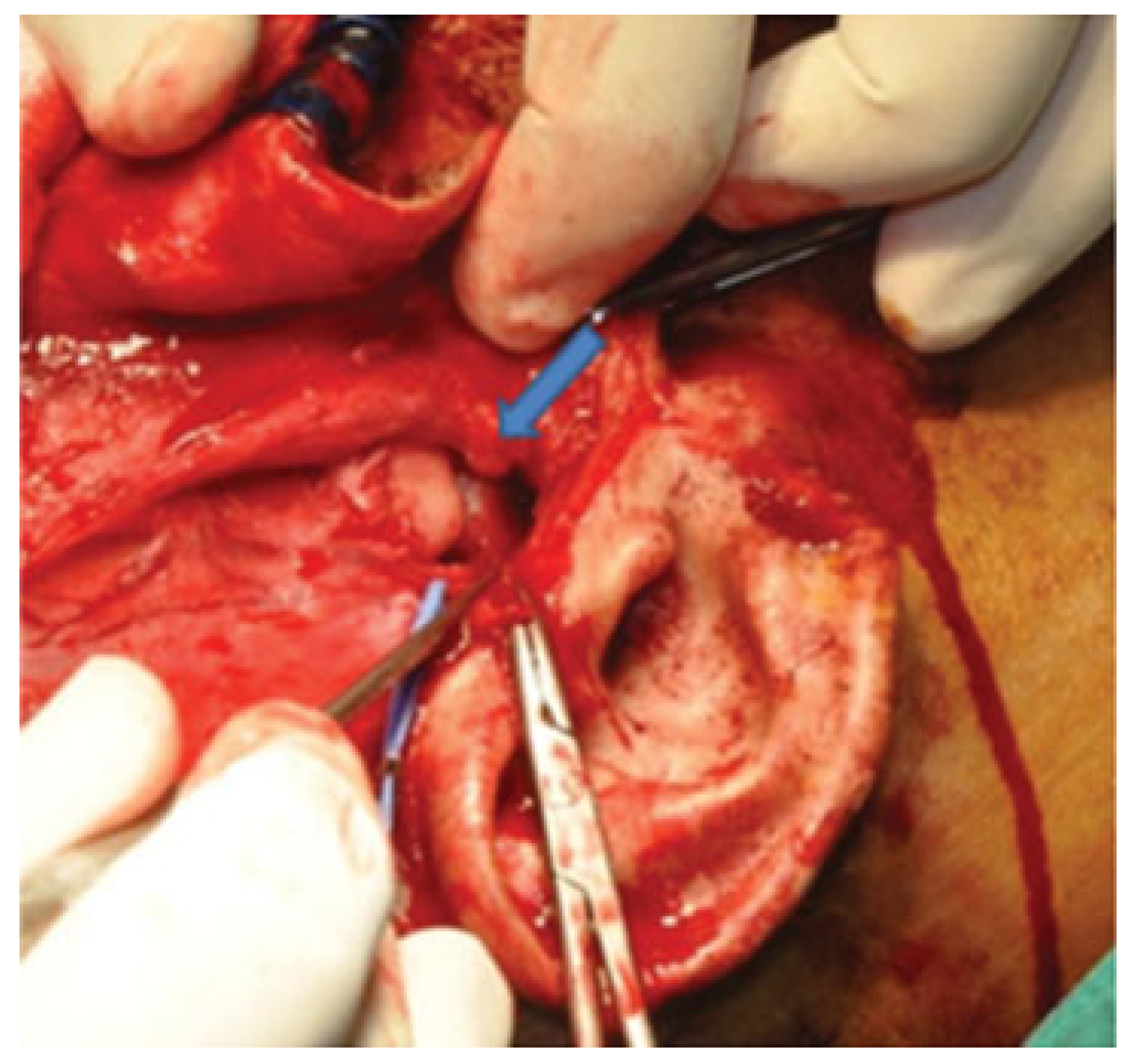

The glenoid fossae, articular eminences, and both dislocated mandibular condyles were fully exposed. Wasting of the temporalis muscle was noted. It became clear at this point that initial manipulation of the mandible to relocate the condylar heads into glenoid fossae was unsuccessful due to the presence of thick fibrous tissues around the TMJ capsules ([

Figure 3]). These fibrous tissues were then released and both TMJ capsules were cut. Rowe’s elevator was used to torque the mandibular condyles back into glenoid fossae. However, difficulty was encountered on the left side; thus, left eminectomy was decided ([

Figure 4]).

The part of the eminence to be resected was marked using a round bur. The cut was deepened using a fissure bur, followed by chisel and mallet to complete the resection. The rough bony edges were smoothened by a vulcanite burr and bone file. At the end of this step, repositioning of the left condylar head became easier. The best occlusion achievable was a Class III position with bilateral buccal crossbites. Hemostasis was achieved and surgical incisions were closed in layers.

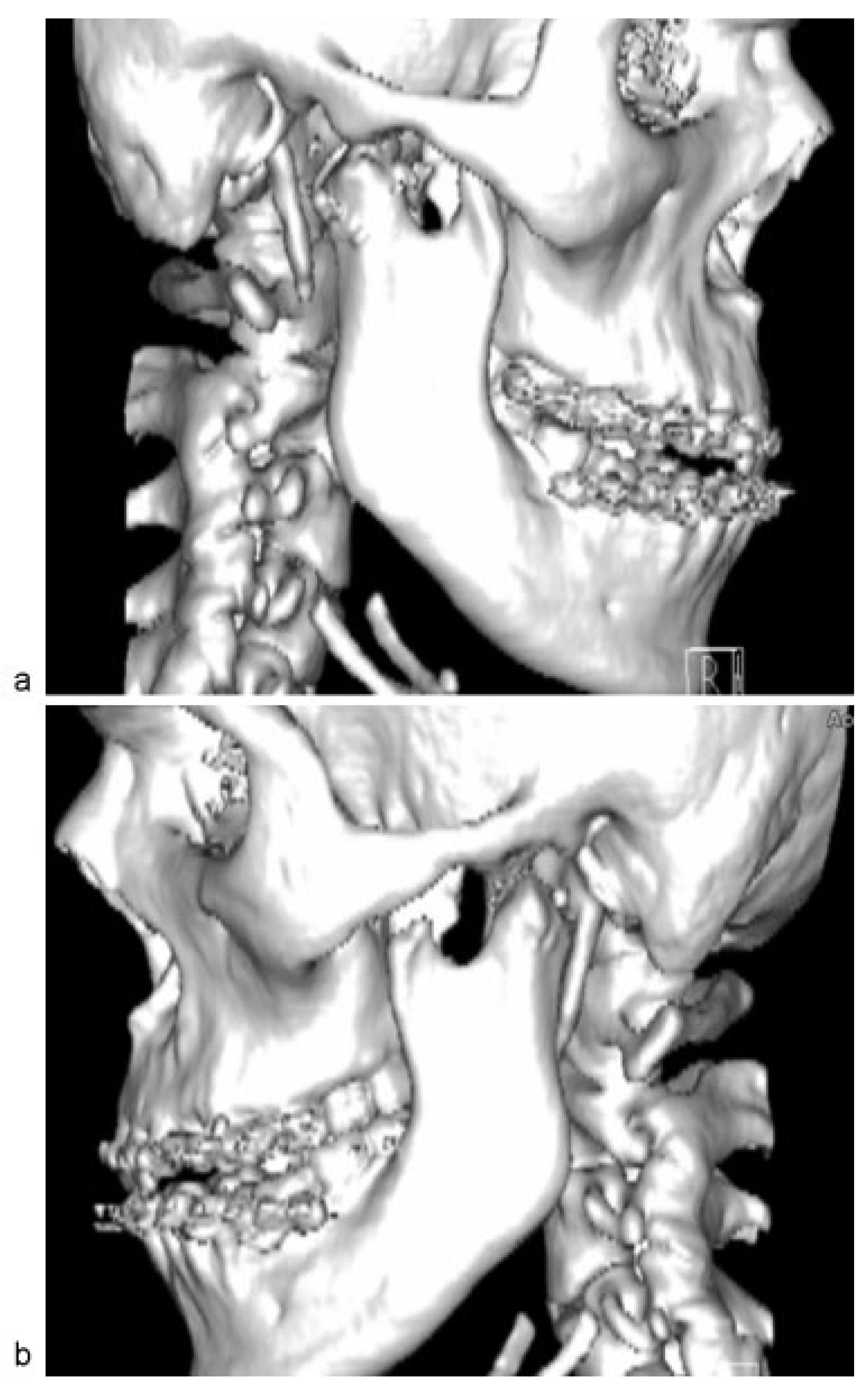

Arch bars were applied to upper and lower teeth. The patient was subjected to 2 weeks of intermaxillary fixation (IMF) to keep the condyles in new position and then continued on elastics training. CT scan immediately postoperative shows the right condyle inferior to the articular eminence and the left condyle inferior to the left glenoid fossa ([

Figure 5]). Postoperative 1 year review shows satisfactory occlusion ([

Figure 6]). Masticatory function of patient has returned to normal and he was able to take normal diet. No recurrence of the TMJ dislocation was recorded.

Figure 3.

Unsuccessful repositioning of condyle into glenoid fossae. Right condyle was seen just below the right articular eminence after manual reduction (arrow).

Figure 3.

Unsuccessful repositioning of condyle into glenoid fossae. Right condyle was seen just below the right articular eminence after manual reduction (arrow).

Figure 4.

Left articular eminence removed (arrow).

Figure 4.

Left articular eminence removed (arrow).

Figure 5.

(a) Right condylar head directly inferior to right articular eminence. (b) Left condylar head located inferior to left glenoid fossa.

Figure 5.

(a) Right condylar head directly inferior to right articular eminence. (b) Left condylar head located inferior to left glenoid fossa.

Figure 6.

Postoperative 1 year review showed satisfactory occlusion.

Figure 6.

Postoperative 1 year review showed satisfactory occlusion.

Discussion

Anterior TMJ dislocation occurs when one or both mandibular condyles displaced in front of the articular eminence. The majority of cases are nontraumatic. Acute TMJ dislocation is very painful but easy to manage. The conservative manual reduction should be done as early as possible.

Chronic TMJ dislocation is a challenging situation to manage. It can be recurrence or prolonged mandibular dislocation [

12]. The conservative manual reduction should be attempted initially. However, good results are rarely obtained. There is a delay in diagnosis and management of TMJ dislocation of our patient. The exact time of occurrence of the dislocation, whether during intubation, PEG tube insertion, or seizure attacks, was unable to be ascertained owing to patient’s minimal communication and feeding route that eliminated the oral functions, making the detection even later. During airway management, TMJ dislocation could happen any time either during direct laryngoscopy and intubation or extubation or anytime in the postoperative period [

14].

Meanwhile, upper endoscopic procedures in patients with atrophy of muscles of mastication, advancing age, a shallow TMJ, and retching during procedure are more likely to have TMJ dislocation [

15]. There have also been reported TMJ dislocation post seizure [

4] and tetanus infection [

16,

17]. After dislocation occurs, spasms of the masseter and pterygoid muscle worsen over time [

14]. A mandible that remains dislocated for a long period of time induces morphological alterations in the intrinsic and extrinsic ligaments of the TMJ as well as atrophy of masticatory muscles [

11]. In our patient, these anatomical changes make the surgery very challenging. Closed reduction without general anesthesia and muscle relaxants is usually unsuccessful in treating chronic TMJ dislocation and thus failure rate is high [

12]. Some authors have reported conservative methods for chronic recurrent dislocation such as injection into joint space with autologous blood or infiltration into lateral pterygoid with botulinum toxin A [

12].

Although conservative methods such as elastic rubber traction with arch bars and ligature wires or IMF with elastic bands are reported to be useful to achieve reduction in chronic prolonged dislocation [

1,

12], we did not attempt this method in our patient as we believe prolonged period of dislocation makes anatomical changes in the TMJ joint and good results are difficult to obtain thorough this method. The treatment approach selected for this patient was open reduction with eminectomy under general anesthesia. Eminectomy was frequently performed in recurrent or longstanding TMJ dislocation [

18]. Intrinsic and extrinsic ligaments of the TMJ become stretched and unable to restrict anterior condylar excursion anymore [

11]. The rationale behind eminectomy is that if the articular eminence is resected, the condylar head can move freely in and out of the glenoid fossa without the risk of dislocation [

19]. Thus, it removes the mechanical obstacles in the condylar path [

8]. In our patient, we have encountered problem while performing reduction due to the presence of thick fibrous tissue around TMJ capsule. We chose to perform eminectomy on the left side only as we managed to torque back condyle into glenoid fossae on the right side.

Surgery performed in periarticular structure is not associated with occlusal alterations. This procedure maintains the relationship between condyle and articular fossa [

11]. Other common procedures that involve periarticular structures are lateral pterygoid myotomy, articular eminence augmentation with bone grafts, and implants or zygomatic arch downfracturing [

11].

Procedures that involve ramus/condyle are condilotomy, condylectomy, subcondylar osteotomy with coronoidotomy, inverted

L-shaped ramus osteotomy, bilateral sagittal split osteotomy, and modified vertical subsigmoid osteotomy [

7,

12]. Conversely, these procedures do not maintain the relationship between condyle and glenoid fossa. It maintains new joint position and at the same time corrects occlusion. Furthermore, patients are prone to develop malocclusion and internal joint derangement of TMJ postoperatively. Thus, we did not choose these procedures.

Osteotomy was not performed for this patient considering his general condition, as it was deemed too extensive for him. Although the occlusion that was obtained was not perfect, it was satisfactory to restore the patient’s oral function and subsequently improve his quality of life. The patient and his parents seem happy with the result.

Conclusion

Delayed management of bilateral TMJ dislocation is undoubtedly challenging. Diagnosis of TMJ dislocation should be made prompt, especially after every procedure that involves manipulation of the mandible. This can be achieved by asking patients to occlude their teeth together and perform lateral excursions postprocedure. Late detection creates unnecessary discomfort to the patient and results in complex management.