A primary one-stage (soft tissue, hard tissue, or composite) reconstruction is the preferred treatment option over the conventional delayed reconstruction approach. [

8,

9] One-stage reconstruction has been proven to reduce postoperative morbidity, shorten hospitalization, and reduce number of hospital admissions. [

8,

9,

10,

11] Despite various Nigerian publications on CGSWs, [

1,

2,

3,

4] little is known about the current prevalence and changing trends of CGSWs in Northern Nigeria. The objective of this study was to determine the pattern, characteristics, ballistics, and trends of CGSWs managed in a Northern Nigerian tertiary hospital over a 14-year period. This study also seeks to describe the management protocol for CGSWs at the center.

Methods

A retrospective review of all admitted cases of CGSWs from January 2000 to December 2013 at the Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital (AKTH), Kano, was conducted. AKTH is a tertiary health facility located in North-West Nigeria which serves as a major referral center for the region. Information on patients admitted for gunshot wounds for the duration was obtained from admission records. Case files were retrieved from the hospital health registry for analysis. Data retrieved from case files included sociodemographic characteristics, cause of injury, and duration of hospitalization. In addition, clinical and radiological findings, such as exit and entry wound sites, type of wounding object (bullet, pellet, “radiologically missing”), injury patterns/concomitant injuries, details on emergency care, type of definitive care, and complications were also collated.

Data analysis was done using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The period prevalence and 95% confidence interval were computed. Period prevalence before and during the insurgency period was compared using the Pearson chi-square test. Quantitative data were summarized using mean and standard deviation. Differences between means were tested using Student t-test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Management Algorithm for CGSWs

Gunshot patients were admitted through the emergency department of the hospital. Emergency management of fresh gunshot victims was done to stabilize victims following advanced trauma life support protocols. A preliminary survey was done at this time to determine the presence of other injuries which would require further emergent intervention. Following emergency management and patient stabilization, initial surgical management was done which usually involved wound debridement and skeletal stabilization. Minimal soft-tissue revision may be done at this stage with the aim of ensuring soft-tissue coverage of exposed bone. In some cases, definitive surgical management can be done at this time depending on wound severity.

Definitive management was guided by the functional and aesthetic demands related to the injury and could range from local advancement to pedicled flaps with or without bone grafts. Definitive management is often delayed for approximately 7 days after gunshot trauma in our center, to allow proper definition of the wound and defects for reconstruction. Soft-tissue configurational defects were acquired from both firearm-related avulsions and defects created, by the excision of contracture, consequent to healing of “injury altered” soft tissues which grossly limited oral functions. The use of pedicled deltopectoral, sternomastoid, submental, Abbe, forehead,

bandoneon, and other local advancement soft-tissue flaps were frequently employed to restore soft-tissue defects where indicated (

Table 1). These flaps are surgically developed and care is taken so as not to injure their major axial supply. They are subsequently anchored to the prepared recipient tissue bed with sutures for 21 days (for

neovascularization) before insetting the flap and returning the carrier portion. Donor site defects are covered with dermatome-harvested split thickness skin grafts from the hairless and color-matched anterolateral thigh region. Autogenous anterior iliac crest bone grafts are frequently used to bridge composite oromandibular continuity defects anchoring with 2.5-mm nonlocking

stainless steel mandibular reconstruction or miniplates and screws (Orthomax, Navadurga, Gujarat, India). These grafts are harvested using a mallet and chisel and can be used as either bone chips or corticocancellous bone and often used in conjunction with wound-acquired autogenous mandibular fragments.

Results

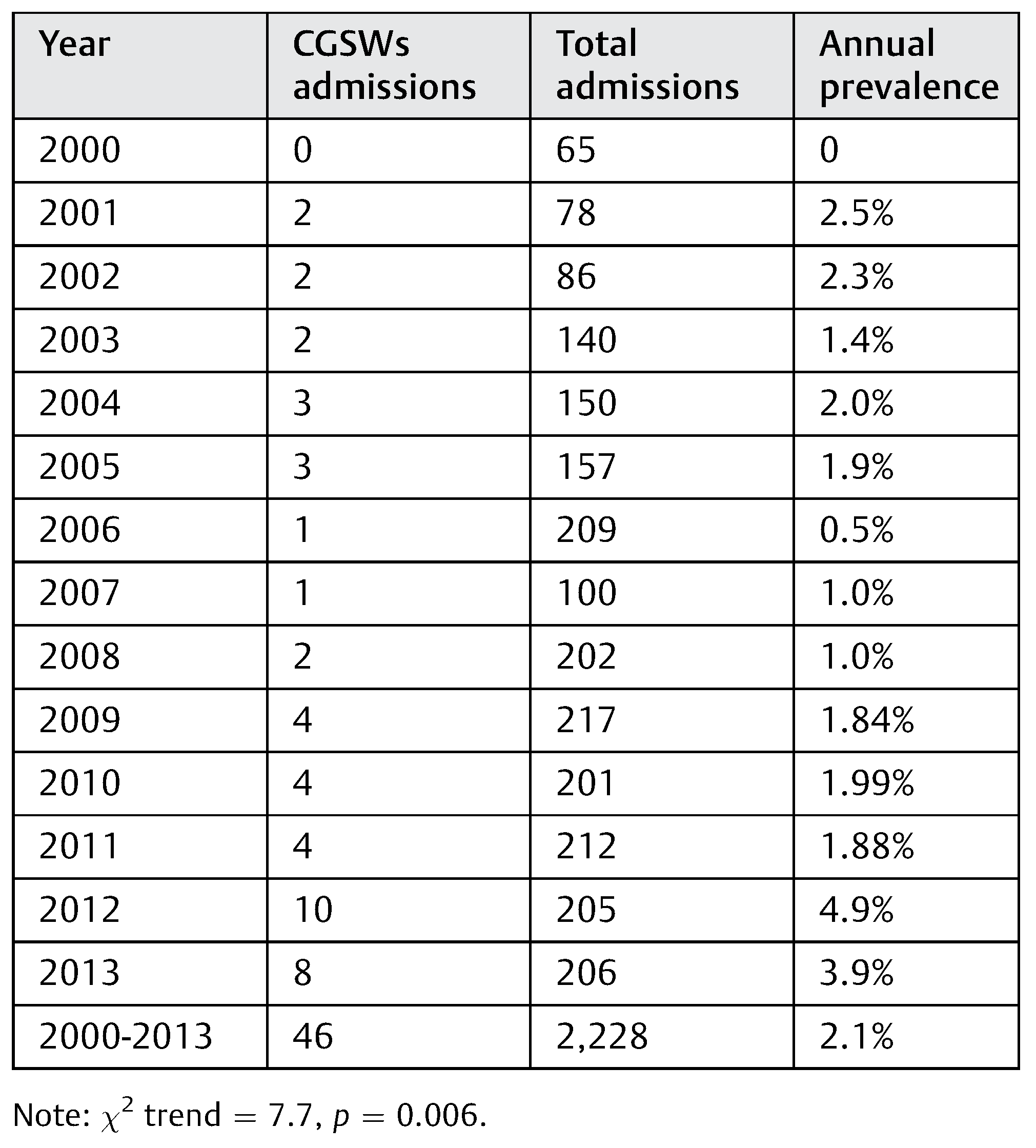

During the study period, 46 CGSW admissions were made from a total of 2,228 maxillofacial inpatient admissions. This gave a period prevalence of 2.1% of maxillofacial admissions. Only six CGSW admissions involved female patients giving a gender ratio (M/F) of 14.3:1. Patients’ ages ranged from 17 to 54 years, with a mean ( SD) of 32.9 8.4 years. The pre-insurgency period (2000–2011) recorded a prevalence percentage of 1.54% (28 CGSWs out of 1,817 admissions) compared with 4.37% that characterized the insurgency period (2012–2013, 18 CGSWs of 411 admissions).

Table 2 shows percentage of the annual prevalence of admissions indicating significant increase in trend of CGSWs over the 14-year period (χ

2 trend = 7.7,

p = 0.006). Majority of CGSW admissions were observed in the past 2 years (2012–2013), as also shown in

Figure 1, with HE CGSWadmissions being greater for this period.

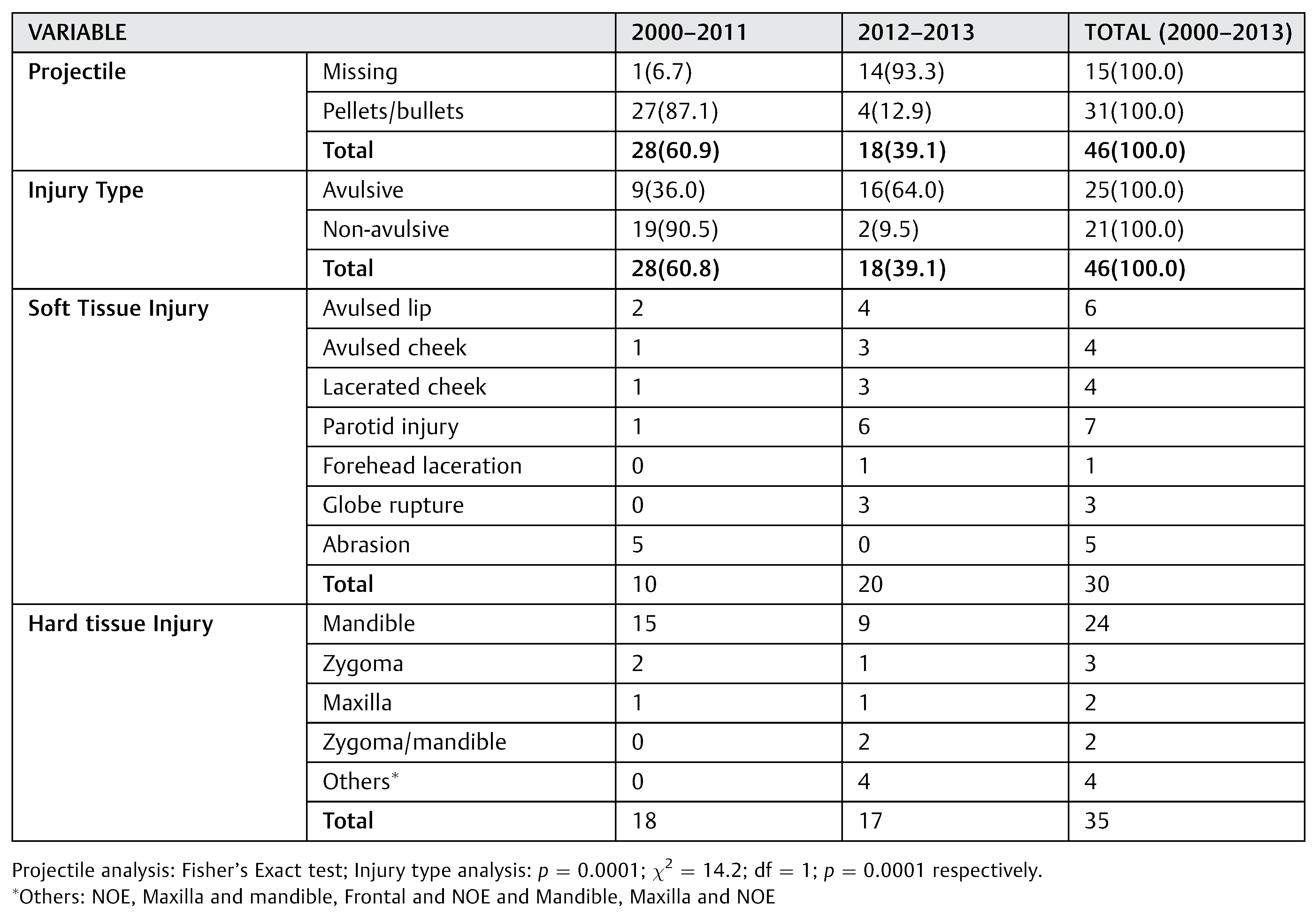

Etiology of injury for the 46 patients over the study duration was armed robbery (31 cases, 67.4%), unknown gunmen (11 cases, 24%), and accidental police discharge (4 cases, 8.7%). For the past 2 years (2012–2013), etiologyof injury was distributed as unknown gunmen (11 cases, 61.1%), armed robbery (6 cases, 33.3%), and police discharge (1 case, 5.6%). Projectile entry points were varied with the mandible having the highest value (16 cases, 33.3%), followed by the cheek (13 cases, 28.3%) and nose (5 cases, 10.9%). Other entry points were the submental region, ear, orbital margins, zygoma, lip (2 cases each, 4.3% each), and temporal and mastoid regions (1 case each, 2.2% each). However, only 15 cases had exit wounds which were also distributed in various sites. It was statistically significant that there were more radiologically identifiable projectiles during the pre-insurgency period than in the period of insurgency (87.1 vs. 12.9%, Fisher exact test, p = 0.0001. This tendency was buttressed by the incidence of greater tissue disruption and avulsions during the insurgency period with a statistically significant difference (χ2 = 14.2, p = 0.0001) due to heavier caliber weapons.

The distribution of injury type along with the pattern of soft- and hard-tissue injuries are presented in

Table 3. Concomitant injuries occurred in seven (15.2%) cases: dura tear in combination with frontal lobe contusion (

n = 2; 4.3%), isolated dura tear (

n = 1), soft-tissue injury to the upper limbs (

n = 3), and bilateral fractured humeri (

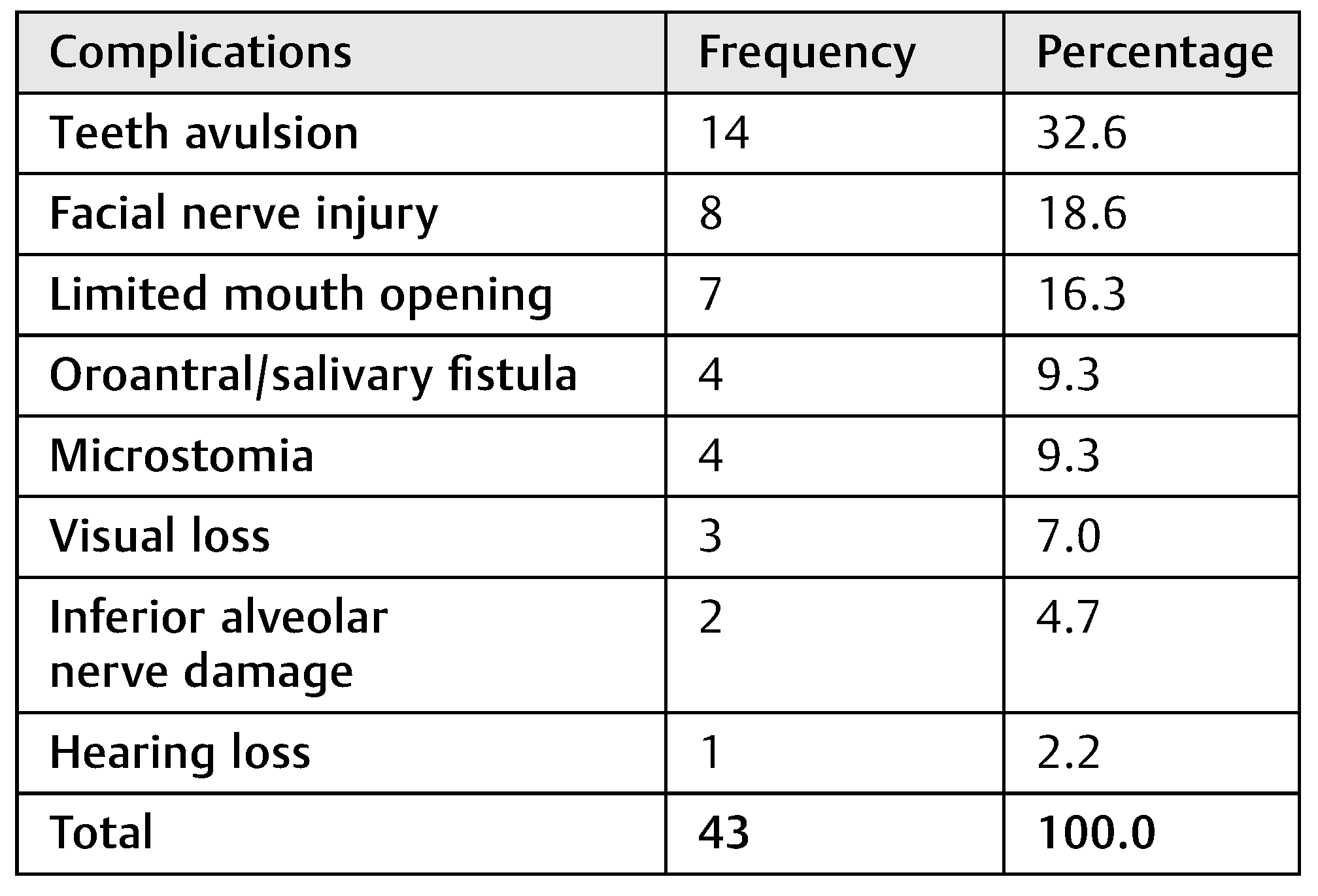

n = 1). Four patients (8.7%) were referred to our center for definitive reconstruction. Preliminary treatment was provided in 42 cases (91.3%). Four of these patients (8.7%) required tracheostomy and one patient (2.2%) required arrest of severe hemorrhage. Tracheostomy was necessitated by severe bilateral mandibular comminution with loss of tongue support (two patients) and bleeding from floor of the mouth/avulsed palatal segments and airway edema (two patients). The observed complications are presented in

Table 4. The management of 18 patients (37%) stopped at emergency care and preliminary management, which involved wound debridement/missile extraction, skeletal stabilization, and suturing.

Table 1 shows the categories of definitive care given in 28 patients with CGSWs.

Twenty-two (47.8%) out of the 46 patients treated required rehabilitation which was in the form of dental prosthesis (n = 8), physiotherapy (n = 6), dental prosthesis/physiotherapy (n = 5), and ocular prosthesis/physiotherapy (n = 3). The duration of hospital stay ranged from 3 to 62 days with mean ( SD) of 17.7 ( 15.56) days.

Discussion

This study was hospital based and retrospective; thus, prevalence rates of CGSWs obtained from such studies may be under-reported. Several patients may have died before reaching the hospital and thus would not be included in these data. Also, several patients may have gone to other hospitals in the region for treatment. An increase in incidence of CGSWs was observed from 2009, with majority of the cases in the final years of the study attributed to “unknown gunmen.” This may be attributable to the activities of religious insurgents/terrorists which appeared to have occurred more as isolated attacks. Insurgency/terrorist activities in Northern Nigeria commenced around September 2009 but reached a peak in January 2012 with more than 3,000 recorded firearm and ordinance explosion deaths. [

12]

There was also a change in pattern of injuries from non-avulsive to avulsive in the later part of the review period. This may be due to a possible change in the ballistics of the weapons used as a result of transition from CGSWs mostly seen from armed robbery to those resulting from terrorist activities. Insurgents may have access to heavy-caliber, military-type weaponry, speculatively from subregional conflicts and peace-keeping missions in Africa which gain entry into the country through various means. [

3,

4]

A comparative analysis of subregional prevalence of CGSWs in Nigeria has shown that etiology varies depending on the socioeconomic, ethnopolitical, and religious indices. In Western Nigeria, Ugboko et al. [

3] reported a predominance of low-energy (LE) CGSWs arising from accidental discharges. Armed robbery attack was the prevailing cause in Eastern and Southern Nigeria. [

4,

13] Young male adults are frequently the victims of CGSWs via armed robbery attack, as they constitute the economically productive age group. [

1] Kaufman et al. [

11] opined that male patients were more often involved in ballistic violence, be it accidental, self-inflicted, suicide, combat, or assault. This was also corroborated by other authors within the country, [

1,

2,

3,

4,

13] the United States, [

7,

10,

11] and other regions. [

6,

8,

14] The strength of this observation is buttressed by a cultural norm of keeping women indoors in Northern Nigeria. [

1]

The severity of firearm-related injuries is determined by ballistics. [

6,

7] This is divided into internal (projectile/propellant interaction), external (influencing flight path, e.g., wind), and terminal ballistics (effect on tissues). [

6] While it was difficult to identify firearm types in this study, the radiological identification of projectile type and comparison with resultant injury pattern [

6,

7] suggested injury classification into the nonavulsive LE injury and avulsive HE injury types.

Nonavulsive LE injury types had small entry wounds with minimal bone destruction and soft-tissue contusions. They are the result of injuries sustained from low-velocity fire-arms (velocity <1,200 ft/s). [

7] Avulsive HE injury types were characterized by osseous comminution with extensive hard- and soft-tissue avulsions. They had small entry points with large cavitating exit wounds with no radiological evidence of the missile, [

7] probably from the

Avtomat Kalashnikova 1947 (AK-47) assault rifle, [

15,

16] being the most common weapon among insurgents. [

16] This weapon [

15,

16] is common among soldiers and terrorists all over the world because it is simple to handle, cheap, lightweight, and readily available, with an estimated 60 to 70 million AK-47 rifles globally. [

17] It fires 7.62 × 39 mm, 125 grain rounds with a very destructive muzzle velocity of approximately 2,330 ft/s. [

17]

The equationE = 1/2 (mass × velocity

2, where E = energy) suggests that the destructive energy quadruples when the velocity doubles. Thus, the greater distribution of injuries and multisystemic involvement which characterized HE injuries is related to this large energy dissipated on impact. It is a combined consequence of pressure wave and energized secondary fragments [

6,

7] as compared with nonavulsive LE injuries. Thelaterhad pelletsor singlebullets(9 mm) associated with simple undisplaced basal bone fractures, crushed dentoalveolar segments, and soft-tissue wounds without exits.

Tracheostomy utilization for CGSWs in our study was lower than that of the findings of Hollier et al. [

10] and Motamedi [

9] who reported 21 and 9%, respectively. This may be because of their larger sample size [

10] and more frequent involvement of intracranial injuries in both studies. [

9,

10] Moreover, the latter [

9] included battlefield injuries with greater tissue disruption and less optimal care in a poorly controlled combat environment. The post-admission mortalities (11 and 2.2%, respectively) reported by both studies may be due to the stated reasons, particularly intracranial involvement. [

7,

17,

18] Prevalence of difficult posttraumatic hemorrhage in our study was low (one patient) probably because the neck [

9,

19] was not involved in our patients and such patients might have died before presentation, thereby being excluded from our data. Control of posttraumatic hemorrhage related to CGSWs can be achieved by ligation of the external carotid artery and pressure. [

11,

19] The benefits of computed tomographic scan (CT) in assessing CGSWs include better visualization of spatial relationships of bone fragments in HE wounds; clearer assessment of continuity defects in its entirety; [

6,

11,

19] and localization of projectile fragments, through visualization of gunpowder residues. [

6] Orbital and cranial involvement was also better appreciated. [

9] However, due to the resource limitation, it is impracticable to make CT scan mandatory for all cases in our center and thus requests are made only where it would influence treatment (

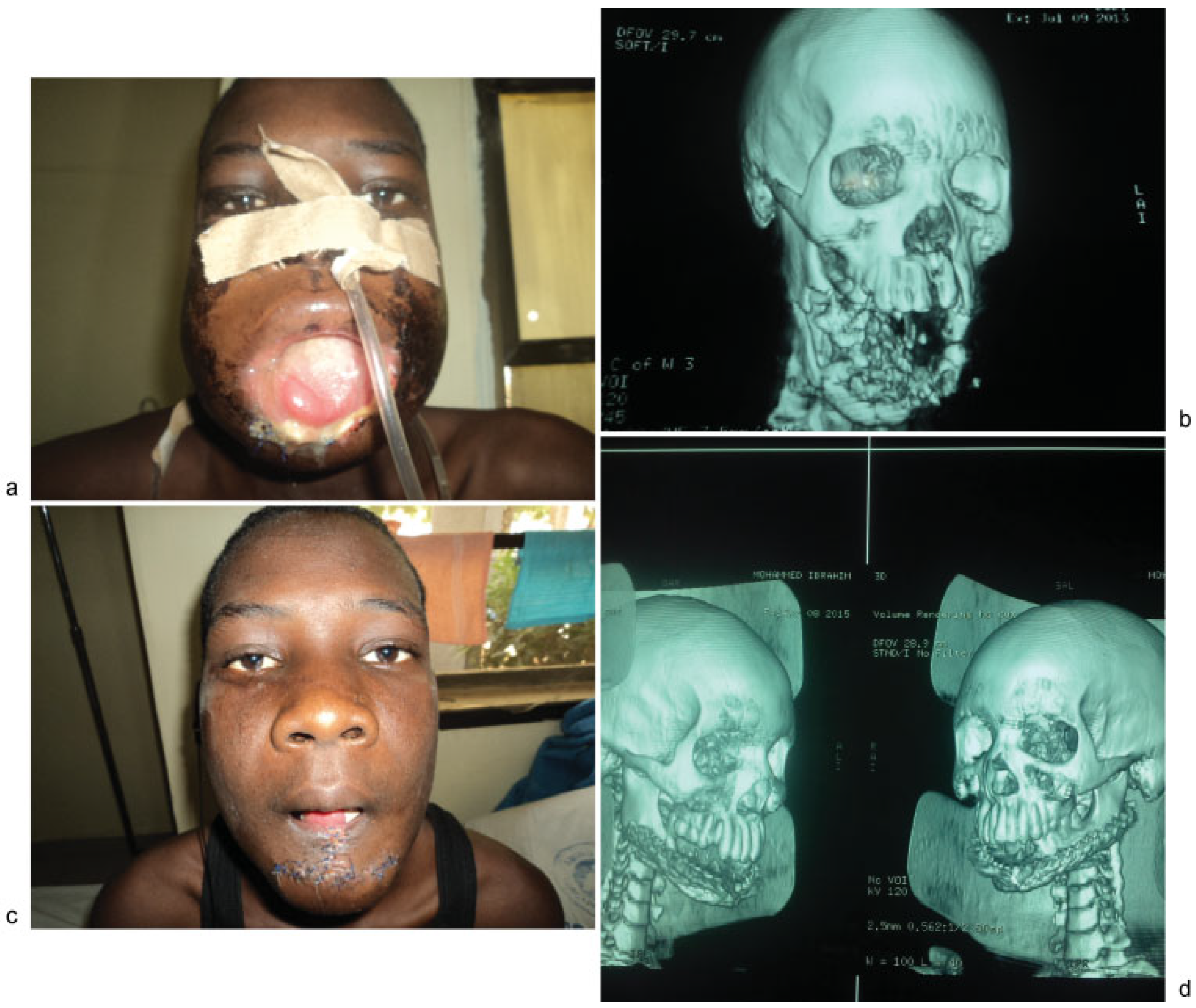

Figure 2a–d)

Contemporary paradigm suggests that the first major surgery should be performed with the intent to definitively manage all aspects of the injuries within 48 hours [

10,

11,

19,

20] (primary treatment). Our experience has shown that wound contamination, secondary infection, and poor clinical status often compromise early reconstruction attempts in our environment. We have thus adopted the delayed approach to management of CGSWs. Reduction of posttraumatic edema, reduced infection rates, and less necrotic debris have been highlighted as some of thebenefits ofdelayed reconstruction. [

21]

Vásconez et al., [

21] however, observed no significant difference in infection rates between both groups, stating that delayed reconstruction resulted in debilitating wound contracture, evidenced

by limitation of mouth opening which often made prosthetic rehabilitation difficult. [

19] Furthermore, immediate reconstruction reduces local dead space, thus enhancing tissue immunoreactivity, robust biologic coverage, and expediting wound healing through better access to hematogenous nutrients. [

22,

23] These benefits suggest that patients who had immediate reconstruction experience better healing and have fewer and less complex surgical revisions than the delayed reconstruction group. [

9,

11]

The iliac crest is a suitable choice for nonvascularized graft to restore bony continuity especially in the mandible because of its dimensional similarity to natural mandible and ease of harvest. [

11,

20] Our choice of stainless steel–based fixation devices over the titanium-based equivalent is secondary to the high cost of the latter, despite its obvious benefits of greater biocompatibility and malleability. The use of pedicled deltopectoral, sternomastoid, submental, Abbe, forehead,

bandoneon, and other local advancement soft-tissue flaps for soft-tissue reconstruction is based on their ready availability and their pedigree as reliable alternatives to microvascular tissue transfers. [

24] These locoregional flaps [

24] with good technique are highly vascular, easy to develop, provide good color match, and hardly fail. The donor-site morbidity is often acceptable to the patient who has been properly consented prior to the procedure and is often skin grafted [

24] (

Figure 3d).

Figure 3(a–c) demonstrates a GSW patient with composite alveolo-palatal defect who had soft-tissue reconstruction with pedicled forehead flap. An interim clasped hollow box obturator was later used to reconstruct the anterior maxillary defect pending bone grafting.

The use of delayed approach to management frequently prolongs hospital stayas seen in our study. This is in addition to reduction in ridge height and loss of sulcular depth that is often associated with our bone replacement technique, as some patients found denture wearing difficult. Hospital stay may be further lengthened in those patients requiring pedicled flaps for soft-tissue reconstruction. Vascularized grafts using microvascular techniques would be a preferable approach where available. Unfortunately, the armamentarium and required expertise are currently not available in our center.