Indians with injuries are reported to be six times more at risk of death as compared with their counterparts from developed countries [

5]. Therefore, maxillofacial injury management requires adequate patient documentation, injury surveillance, and re-creation of data that adequately describe the whole spectrum of injuries [

6]. This would enable health planners and providers to specifically address the burden of maxillofacial injuries, and thus develop suitable preventive programs aimed at lowering the incidence of these through more efficient planning for resource allocation and delivering adequate care [

7,

8,

9]. The etiology of facial trauma also affects the incidence, clinical presentation, and treatment modalities of the facial fracture, and it is influenced by sociodemographic, economic, and cultural factors of the population being studied [

8].

The aim of this unicenter-based retrospective study conducted over a period of 1 year was to obtain a dependable epidemiologic data focusing on the analysis of the variation in causes and characteristics of maxillofacial fractures managed at our center, to highlight the underlying principles and formulate treatment guidelines by identifying, describing and quantifying trauma for use in planning and evaluation of preventive programs.

Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India. No ethical committee approval was obtained as this was a retrospective study taken from departmental medical records. This study was based on a systematic computer-assisted database search that allowed extraction of retrospective data of the patients who reported to our outpatient unit and emergency department (ED) including those who were hospitalized, from March 2015 to March 2016. Patients of both sexes and all age groups with clinically and radiographically diagnosed maxillofacial fractures (with or without contiguous bodily fractures/injuries) were included in this study. Exclusion of patients with incomplete records was done.

The following data were recorded for each patient: demographics (sex, age), etiology, geographic distribution, date of injury, site of facial fractures, number of fractures (single, two, or multiple), associated soft tissue and dentoalveolar injury, and type of intervention.

No formal sample size was calculated and all 1,000 patients who met the inclusion criteria during the study period were included. The patients’ age ranged from 0 to 94 years, and they were divided into eight age groups: 0 to 10, 11 to 20, 21 to 30, 31 to 40, 41 to 50, 51 to 60, 61 to 70, and older than 80 years. The following categories of cause of injury were considered: physical assaults (PAs), falls, and RTA. RTAs were analyzed and recorded according to type of vehicle, that is, two wheeler, four wheeler (heavy motor/light motor vehicle), position of the victim (driver/pillion rider). The dates of injury were grouped and analyzed according to the month of occurrence.

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution.

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution.

Fractures were evaluated for site and number that had been determined with clinical evaluation assisted with conventional radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scans and classified as fractures of the mandible, orbital-zygomaticmaxillary complex (OZMC), orbit, nose, LeFort, and nasoorbital-ethmoid (NOE) fracture. Mandibular fractures included fractures of the symphysis, parasymphysis, body, angle, ramus, coronoid, and condyle. Patients with isolated skull fractures and only minor superficial soft tissue injuries were excluded from our study. Sex-wise distribution of site of facial injuries was also done. Treatment was broadly divided into those who had undergone open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) and those who had been treated conservatively by closed reduction.

Data were presented using descriptive analyses. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to identify demographic and injury-related factors associated with outcome. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 16, IBM, Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses and a p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Site of Fracture

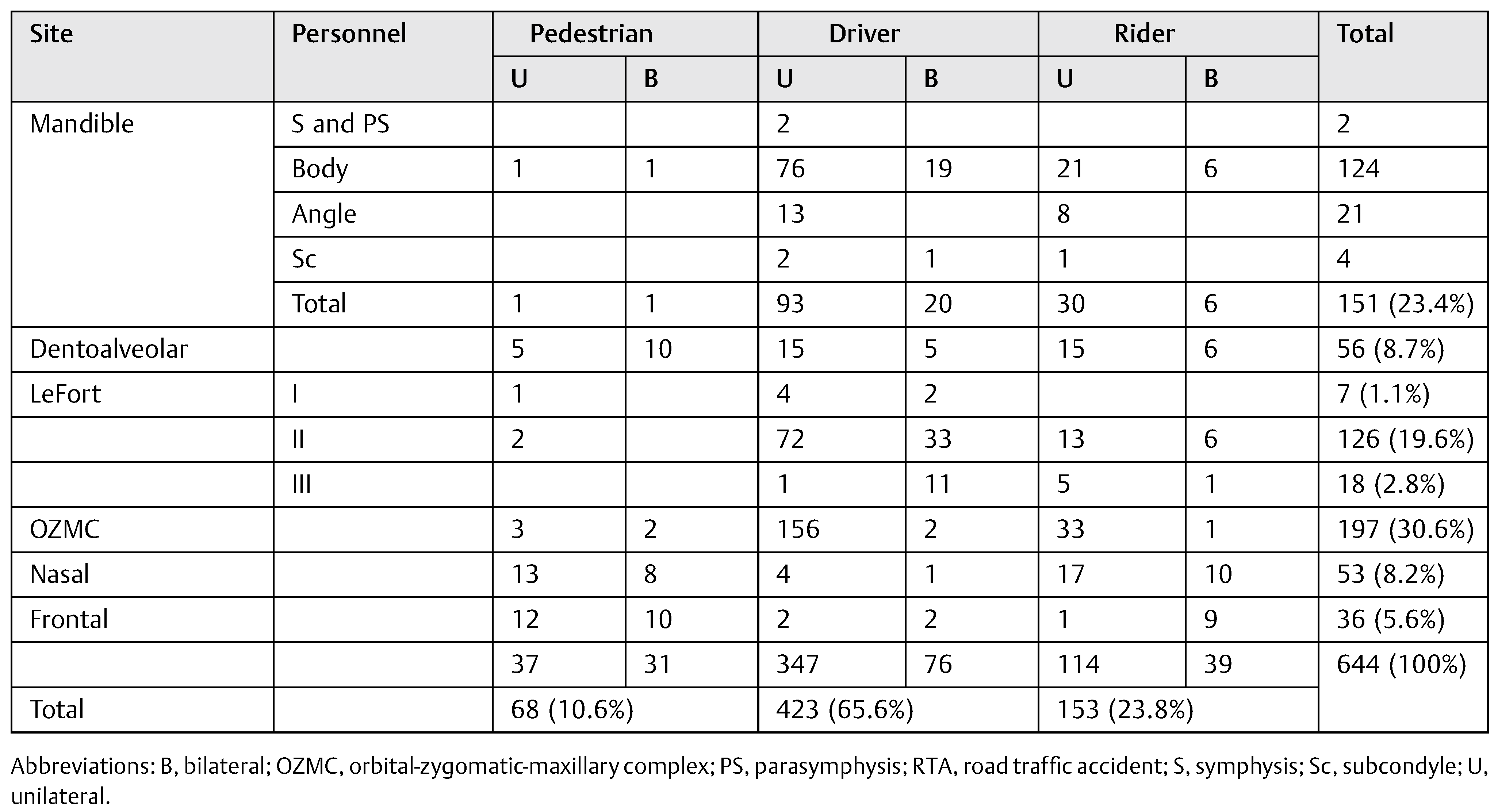

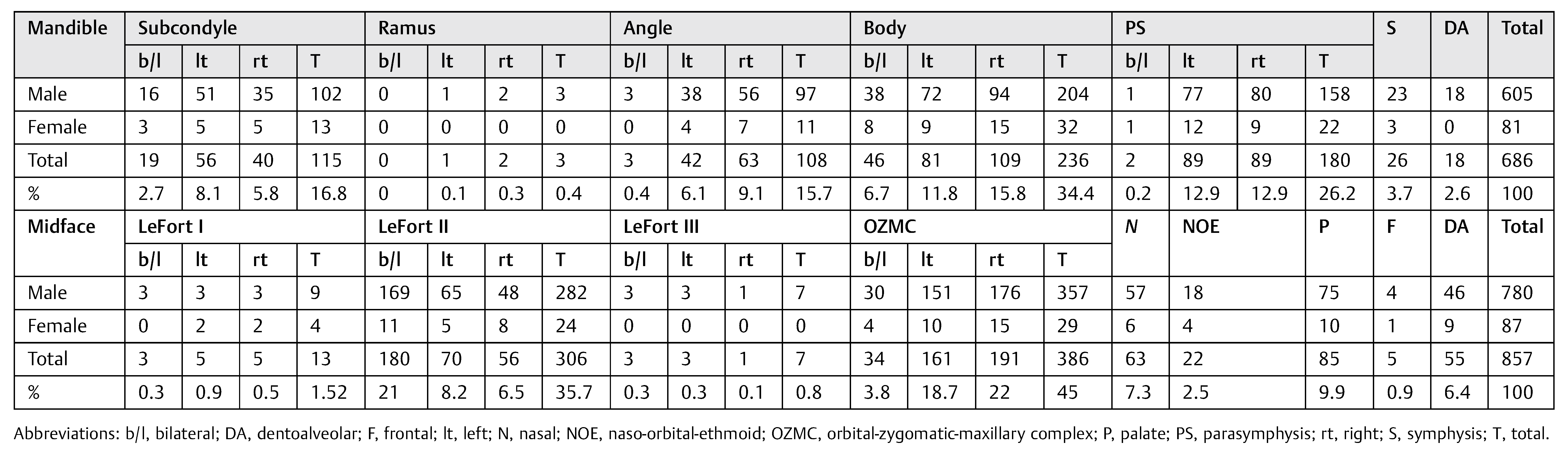

Among the facial fractures, the mandibular fractures (

Table 6) amounted to 686 (44.5%) and the most common site of fracture was the mandibular body (34.4%—46 bilateral, 81 left, and 109 right). 115 subcondyle (16.8%), 3 ramus (0.4%), 108 angle (15.7%), 236 body (34.4%), 180 parasymphysis (26.2%), 26 symphysis (3.7%), and 18 dentoalveolar fractures (2.6%) were encountered. Among the 857 (55.5%) fractures of the midface, OZMC fractures were most common (45%). A total of 13 (15.2%) LeFort I, 306 (35.7%) LeFort II, 7 (0.8%) LeFort III, 386 (45%) OZMC, 63 (7.3%) nasal, 22 (2.5%) NOE, 5 (0.9%) frontal, 85 (9.9%) temporal, and 55 (6.4%) maxillary dentoalveolar fractures were observed.

Fractures of the right side were more common (556, 36.03%) than left (508, 32.9%) and bilateral fractures were least common (425, 27.5%). Left subcondylar fractures outnumbered the ones on the right (1.4:1) and parasymphysis fractures were encountered equally on both sides. Most common bilateral fractures were those of the mandibular body (6.7%).

The mandibular fracture pattern showed that isolated mandibular fractures were most common (457, 29.6%), 222 (14.38%) patients had fractures at two locations and more than two fractures were seen in 7(0.45%) patients (

Table 7). Among midface fractures, the number of patients with single, double, and multiple fractures was 480 (31.10%), 367 (23.78%), 10 (0.64%), respectively. Most common isolated fractures were nasal and OZMC. Males encountered a total of 862 (55.87%) fractures whereas females had 681 (44.13%) fractures; 937 patients had a single isolated facial fracture (60.7%), 589 (38.17%) had two sites fractured, whereas only 17 patients had more than 2 (1.1%) fractures.

Table 5.

Seasonal distribution of mode of trauma.

Table 5.

Seasonal distribution of mode of trauma.

Discussion

The epidemiology of maxillofacial fractures is considerably variable [

9,

10,

11]. Frequencies differ both within and between countries depending on contributing entities such as environmental, cultural, and socioeconomic factors [

10,

11]. Our study demonstrates the pattern of trauma in a population of Uttar Pradesh, India, over a period of 1 year.

Our patients were predominantly male, as in previous studies [

12]. The male:female ratio (8:1) was higher than those reported in developed countries (3:1) [

12] but corresponded to those of developing ones (7:1) [

13]. The demographic characteristics of maxillofacial fractures differs significantly between both genders [

14]. The majority of fractures seen in males were most likely due to higher physical activity, more involvement in road accidents, altercations, and work-related casualties [

8]. Lesser incidence of maxillofacial fractures in females could be because of lesser reporting of injuries [

15]—due to either the sex-based neglect still prevalent in many rural areas or domestic abuse.

Table 6.

Distribution of mandibular and midface fractures.

Table 6.

Distribution of mandibular and midface fractures.

Table 7.

Number of fractures.

Table 7.

Number of fractures.

Table 8.

Treatment distribution of mandibular and midface fractures.

Table 8.

Treatment distribution of mandibular and midface fractures.

Most fractures occurred between the first and fourth decades, as reported earlier [

16]. The observation that men aged between 21 and 30 years had the highest frequency of facial fractures is consistent with literature [

10,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Pediatric fractures accounted for 16.6% in our study (predominantly due to falls). In agreement with previous studies, we observed the rarity of facial fractures before 5 years of age, while their incidence progressively increases with the beginning of school and adolescence [

22].

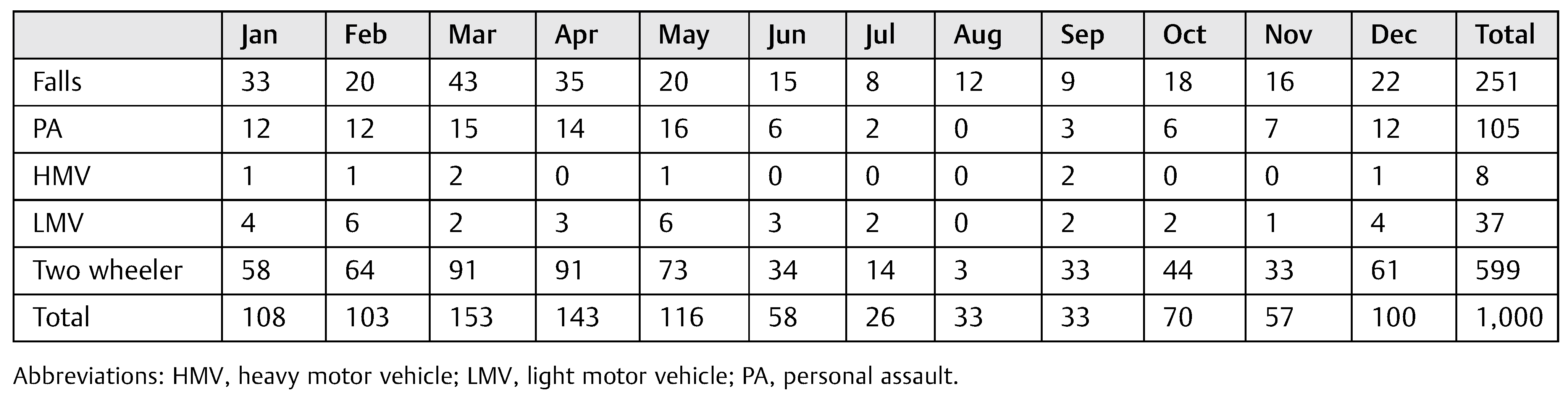

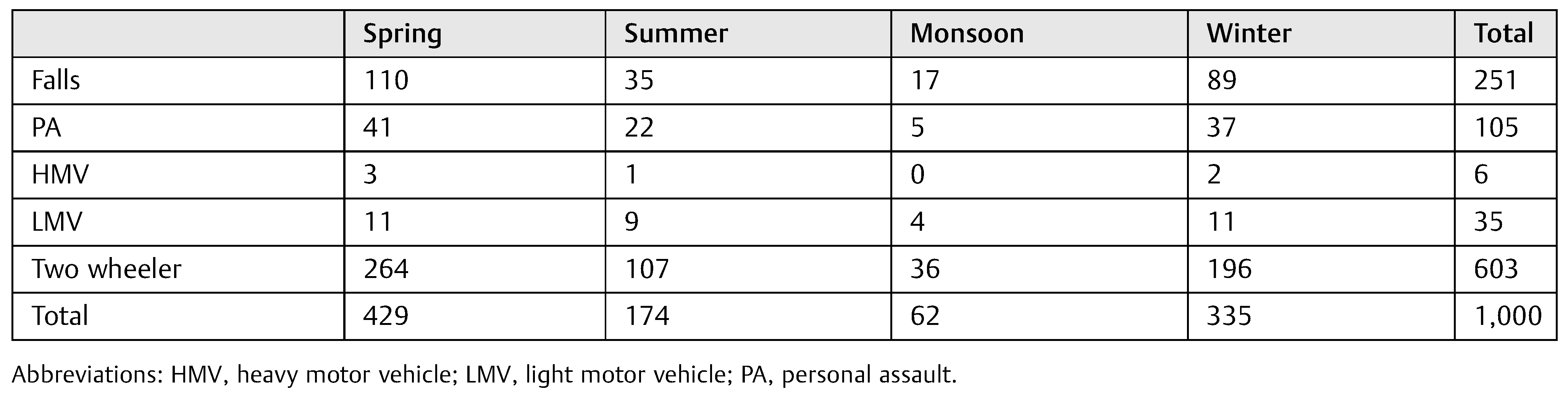

A peak in incidence of maxillofacial fractures in March to April was in accordance with many authors [

7] with peak seasonal distribution observed in spring and winter in contrast to studies in which most injuries are reported during summer [

8,

16,

23].

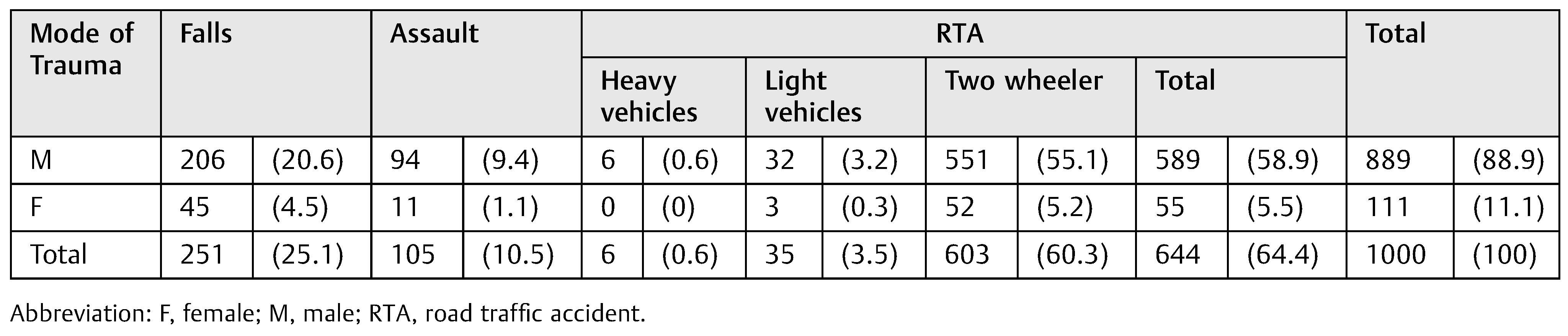

RTAs, assaults, and falls are the leading causes of maxillofacial fractures worldwide. The main cause of fractures in males was RTA [

19,

20,

24]. It was striking that male vehicle drivers sustaining facial fractures far outnumbered female drivers, confirming the risk-taking behavior of young men [

25]. Inadequate road safety awareness, unsuitable road conditions, violation of speed limits, ill-maintained vehicles without safety features, failure to wear seat belts or helmets, entry into opposite traffic lanes, violation of the highway code, use of alcohol or other intoxicating agents, behavioral disorders, and socioeconomical insufficiencies of some drivers are the cardinal reasons for the large numbers of RTA in India. Two-wheeler accidents predominate as a result of inattention and poor road conditions [

4].

Fall-related facial injuries were the second most common cause of facial bone fractures, seen predominantly in elderly population, especially affecting the mandible, was similar to previous studies [

22,

26]. Assault was the third most common cause of facial injury, the magnitude of which is lesser (10.5%) compared with that reported (13–90%) by other countries [

27,

28] and reported as the leading cause by a few countries [

22,

29].

There is a stark difference between the incidence and etiology of trauma in developed and developing countries. In American, African, and Asian countries, road traffic crashes have been shown to be the predominant cause [

24]. The EURMAT (European Maxillofacial Trauma) collaboration highlights the changing trend in maxillofacial trauma epidemiology in European countries, with trauma caused by assaults and falls now outnumbering those due to RTA [

29]. The longevity of the European population, in addition to strict road and work legislation, could be responsible for this change [

29]. In Oceania assaults are predominant [

24]. This variation in etiology of trauma across the globe warrants the knowledge of different laws (regarding factors, e.g., traffic, vehicles, sports, and interpersonal violence) in different countries to allow for improvement in maxillofacial trauma incidence rates.

Fractures that occur most frequently following the assault include the nasal bones, mandible, zygoma, and midface in descending order [

30]. Nasal bone fractures have been reported as the most frequent midfacial fractures [

14] because of facial prominence, lack of soft tissue, and being an easy target in violence attacks, making them the most fragile facial bones. Remarkably, fewer nasal bone fractures were noted in this study. In the midface, the zygoma was frequently involved, as it is an anatomic structure susceptible to injury by external force [

8,

31]. The majority of fractures were of the midface [

4,

12,

26], the larger proportion of which were bilateral, more commonly being caused by high velocity trauma of RTAs. When analyzing fractures individually, the most common site was the mandible, consistent with studies [

12,

31,

32], probably as it occupies a larger vulnerable area in the facial skeleton. A majority of patients (60.7%) experienced trauma to a single bone, in contrast to previous research [

21].

As plate osteosynthesis has become the state of the art in the treatment of facial fractures, 46.2% of cases were treated with the open method with use of plating systems [

27,

33]. Most mandibular fractures (64%) were treated by open reduction [

21,

34]. Open reduction can prevent unwanted sequelae such as body weight reduction, poor oral hygiene, speech difficulties, and periodontal disease associated with the closed reduction. Our results correspond with previous studies [

10,

19,

35] in which open reduction was lesser frequently used. This can be attributed to closed reduction being economically profitable for people in developing countries in poorer living standards. The disparity in ORIF rates with only 32% midface fractures undergoing ORIF can be due to more amounts of nasal, frontal, and zygomatic arch fractures being treated by closed reduction. Also, this is the choice of management in medically compromised or noncompliant patients [

34].

Limitations of the study is that being retrospective, it may be subject to information bias due to inaccurate initial examination and incomplete or incorrect documentation. Also, the study population was obtained from a single trauma center and could possibly not reflect the experience at centers with a concoction of presentations. Details of drinking and driving and use of helmets were not included.

However, the results provide vital information required to excogitate plans for preventive measures to reduce the frequency of maxillofacial fractures, which when associated with other injuries due to RTA, are grueling to treat. Socioeconomic consequences of facial fractures include the cost of treatment and hospital admission, hospital resources, and loss of revenue [

36]. Consequences for patients include functional, psychological, aesthetic, emotional, and financial problems. India, a developing nation with a humongous population and rising economy, has massive traffic issues with increasing number of accidents every year, mostly due to the complete disregard of traffic rules and dismal abidance of laws for compulsory helmet and seat belt use. Most drivers are unlicensed, uneducated, do not maintain vehicles, and drive under the influence of alcohol [

37].

The only cure for the trauma epidemic is injury prevention. Preventive measures such as wearing helmets and using restraints reduce facial injuries by 65% [

38] and 25% [

36], respectively. Lower limits of motor vehicle speed in urban areas, road safety training for adolescents, and lanes to segregate two wheelers from motor vehicles [

39] should also prove helpful. Strict enforcement of existing traffic regulations, formulation of new staunch traffic policies, reinforcement of legislation aimed to prevent RTA, and educating people about safety guidelines before and after vehicles purchase are the need of the hour in our country to reduce traffic accidents. The trauma burden due to falls and PA could also be reduced by better care and vigilance of the elderly population and harsher laws for those engaging in interpersonal violence.