Abstract

To date, research which integrates corporate governance and risk management has been limited. Yet, risk exposure and management are increasingly becoming the core function of modern business enterprises in various sectors and industries domestically and globally. Risk identification and management are crucial in any business strategy design and implementation. From the investors’ point of view, knowledge of the risk profile, risk appetite and risk management are key elements in making sound portfolio investment decisions. This paper examines the relationships between corporate governance mechanisms and risk disclosure behavior using a sample of Canadian publicly-traded companies (TSX 230). Results show that Canadian public companies are more likely to disclose risk management information over and above the mandatory risk disclosures, if they are larger in size and if their boards of directors have more independent members. Minority voting control ownership structures appear to negatively impact risk disclosure and CEO incentive compensation shows mixed results. The paper concludes that more research is needed to further assess the impact of various governance mechanisms on corporate risk management and disclosure behavior.

Keywords:

Corporate governance; Enterprise risk management; Agency costs; Fraction of controlling votes; Risk disclosure JEL classification:

G32; G38

1. REGULATORY FRAMEWORK FOR RISK DISCLOSURE AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

Financial accounting standards bodies and security exchange commissions, both in Canada and the United States, require “business entities” to provide information to financial statement users regarding their exposure to risk. Financial and market risk disclosures (such as currency, interest rate and credit risks) are the most regulated categories of risk (see for example Lajili and Zeghal, 2005). In particular, the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (or CICA) Handbook (Section 3860) requires that firms disclose any information that assists users of financial statements in assessing the extent of risk related financial instruments use such as the extent and nature of the financial instruments including the terms and conditions. The risks listed in paragraph 44 of this section include: price risk (currency, interest rate, and market risk), credit, liquidity, and cash flow risk. Furthermore, the CICA Handbook states that: “…entities are encouraged to provide a discussion of the extent to which financial instruments are used, the associated risks and the business purposes served” (CICA Handbook, section 3860 paragraph 43). Thus, mandatory risk disclosures concern primarily financial instruments use and are usually reported in the footnotes to the financial statements. Qualitative or quantitative discussions of the risks associated with the use of financial instruments and management’s policies to control those risks are currently voluntary to a great extent. While the Canadian regulations appear to deal more broadly with different types of financial instruments use and exposure disclosures, the US GAAP regulations contain more specific, detailed and usually more complex risk disclosure requirements. For instance, SFAS 107 “Disclosure about fair value of financial instruments” and SFAS 133 “Accounting for derivative instruments and hedging activities” establish accounting and reporting standards for financial instruments and derivative instruments respectively. In particular, SFAS 133 requires that an entity recognizes all derivatives as either assets or liabilities in the statement of financial position and measure those instruments at fair value.

In addition to the financial reporting statements for risk disclosure summarized above, securities exchange regulators both in Canada and the US, require that registrant firms disclose certain information (including risk) mainly in the MD&A section of the annual reports. Forward-looking information is only encouraged in Canada presently in contrast with the US exchange rules where the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires companies to provide both quantitative and qualitative disclosures about market risk including forward-looking information (e.g., FRR No. 48). Non-financial types of risk are currently disclosed on a voluntary basis to a large extent and mostly in the MD&A sections under the condition of “materiality” and “significant risk exposure,” which might give management a chance to exercise their discretion in choosing to publicly disclose potentially relevant risk information.

With regard to corporate governance, The CICA 2001 report on corporate governance in Canada highlights the role that boards of directors should play in corporate governance and proposes amendments to the disclosure requirements and guidelines by the Toronto Stock Exchange (sections 473 to 475). In the US, the recent COSO (i.e., Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission) report (2004) proposes a global framework for enterprise risk management to facilitate information sharing and communication between directors, managers and other employees. The CICA (2001) report stresses the distinction and separation between managing or running the firm (management’s role) and overseeing and monitoring management’s actions and decisions and holding it to account (the board of director’s major role). This view is consistent with agency theory since it emphasizes the separation between the agent’s and the principal’s actions and responsibilities and also the separation of ownership and control since the board of directors exist to protect the best interests of the shareholders.

2. PRIOR RELATED RESEARCH AND STUDY’S HYPOTHESES

Most recent research in the finance and accounting literature have examined firm risk exposure and corporate governance structure as it relates to firm performance, value, and audit pricing decisions, among others (e.g., Beasley et al. 2005, Bedard and Johnstone 2004, Cronqvist and Nilsson 2003, Gompers, Ishii and Metrick 2003, Cohen et al. 2002, Beasley and Salterio 2001). Generally, the findings from these studies lend support to agency theory predictions with regard to the effects of the separation of ownership and control and related agency costs on firm value. For example, from a sample of Swedish public firms, Cronqvist and Nilsson (2003) document a significant decrease in firm value (Tobin’s q) associated with controlling vote ownership or a controlling minority shareholder (or CMS) governance structure. Family CMSs were also found to be associated with the highest firm value discount among all controlling owner categories such as corporations and financial institutions. An important implication of this result is that the higher the agency costs borne by a firm or organization, the lower the expected market performance of the firm and consequently its value in the market.

Agency relationships are complex and difficult to manage because the principal cannot perfectly and cheaply monitor the agent’s behavior, actions and information (e.g., Jensen and Meckling 1976). However, the more control the principal exerts over financial and other relevant economic resources in the business organization, the more likely he/she will be able to control and effectively oversee the agent’s actions and effort. In agency theory, the crucial question comes down to finding the most efficient or optimal incentive compensation contracts and information alignment schemes between the principal and the agent, a challenging undertaking both in theory and in practice. The design of relevant and reliable managerial performance measures, the degree of risk exposure and risk sharing involved in different compensation schemes, as well as the parties’ utility functions and compensation preferences, should all be examined thoroughly before such a contracting scheme is adopted. Further, and since contracts are by nature incomplete (e.g., Hart 1988) and not comprehensive (specifically because of risks and uncertainties in future business transactions and the inability to foresee all possible contingencies), they should be revised and renegotiated on an ongoing basis.

In addition to the agency theory foundations of corporate governance usually captured through the incentive compensation packages and contingent contracts aimed at aligning shareholders and management’s, executive power and control of decision making rights within an organization have led to the development of the managerial or executive power approach to corporate governance and its interaction with organizational and firm performance variables. For instance, Adams et al. (2005) provides evidence that corporate performance (e.g., stock returns) will be more variable if a corporation is run by a powerful CEO with centralized decision making power concentrated in his/her hands. To proxy for CEO power, Adams et. al (2005) uses governance variables such as whether the CEO is also the founder of the company, formal position and titles, and status as the board’s only insider. The paper thus questions the validity and implications of policy recommendations calling for example for the separation of the CEO and chairman of the board functions (i.e., Sarbanes-Oxley Act 2002) because firms run by powerful CEOs could out-perform or under-perform their peers with less powerful CEOs. The current paper also adopts a more integrated approach to corporate governance linking both board and executive characteristics with agency-related governance mechanisms (e.g., incentive compensation and ownership and control variables) to risk management disclosure volume and behavior.

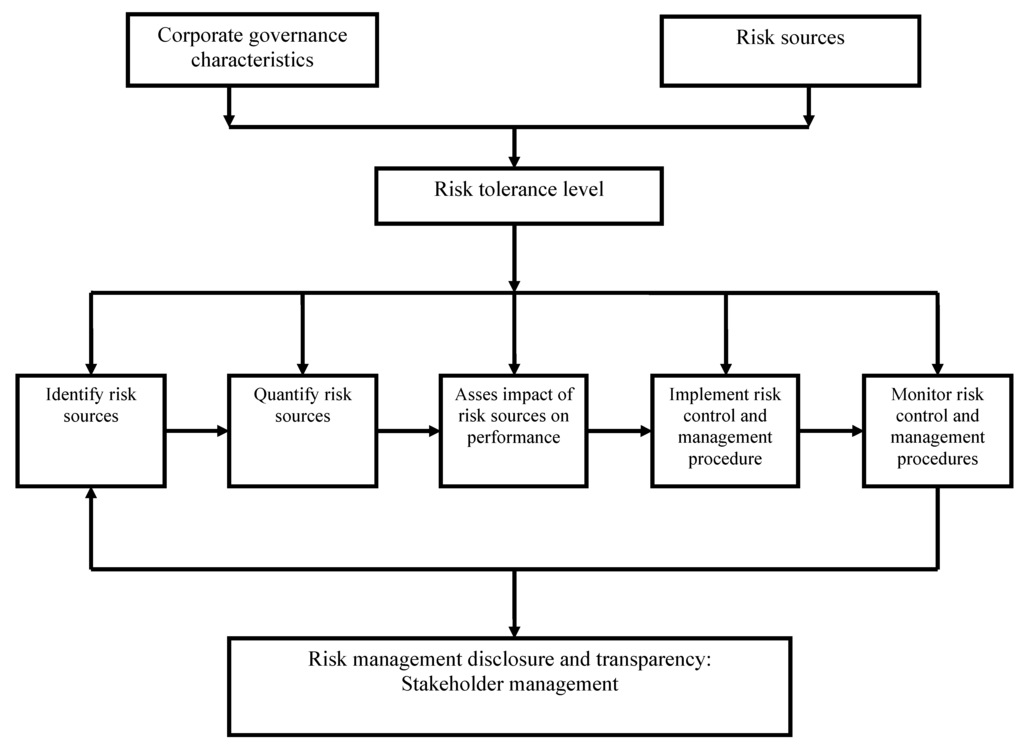

Tufano (1996) examines the impacts of corporate governance mechanisms (executive compensation forms and equity ownership structures) on the degree of financial risk management for a sample of North-American mining firms. The study results highlight the importance of managerial risk aversion and executive risk diversification strategies embedded in their incentive contracts on the degree of corporate risk management. Notably, the study finds that managers who own more shares of the stock of their firms manage more financial risk while those who hold more stock options tend to manage less financial risks, after controlling for other risk management variables such as leverage and the degree of business diversification. A most recent study, Beasley et al. 2005 examines the extent of enterprise risk management (ERM) implementation as it relates to corporate governance and other organizational factors for a sample of 123 American and international organizations. They find that ERM stage of adoption is positively related to certain key governance and organizational factors such as the presence of a chief risk officer, board independence, support shown for ERM from the CEO and CFO, and the presence of a Big Four auditor among other factors. In the current paper, the relationship between risk management information disclosure and corporate governance is empirically investigated. Despite an extensive research on corporate governance and accounting disclosure in prior literature, research linking both governance and risk disclosure in particular is rare (e.g., Lajili and Zeghal 2005, Beasley et al., 2006). The current paper attempts to provide a primary step towards the development of a more systematic approach to corporate governance and risk management and disclosure in the future.

Based on prior literature and this study’s motivations, this study’s research hypotheses are formulated as follows:

- H1: An increase in the number of independent board members positively affects the extent of voluntary risk management disclosure, other things being equal.

- H2. An increase in minority controlling vote ownership structures negatively affects the degree of voluntary risk management disclosure, other things being equal.

- H3. CEO incentive compensation positively affects the degree of voluntary risk management disclosure, other things being equal.

Hypothesis (1) is based on the premise that the higher the proportion of independent directors on the board (all else being the same), the higher the extent of internal controls implemented by the company to provide more transparency and guidance into strategic decision making, performance measurement, and internal (as well as external) audit operations. This hypothesis is consistent with Sarbanes Oxley regulations and prior research (e.g., Beasley et al. 2005). Hypotheses (2) and (3) examine the impact of ownership and control structures and CEO incentive compensation, respectively, on the extent of enterprise risk management disclosures. While hypothesis (2) anticipates a negative relationship between the extent of ERM disclosure and the extent of minority controlling vote ownership structures, hypothesis (3) predicts a positive impact of CEO incentive compensation on ERM disclosure. The underlying argument behind hypothesis (2) sign prediction is grounded in agency theory with regard to the potential conflicts of interests between the minority control owners and the rest of the common shareholder base which would increase total agency costs potentially leading to ineffective corporate governance. To protect their interests, minority control shareholders would be more inclined to disclose less risk and risk management information and thus withhold potentially relevant information on which they could act at their own discretion. Hypothesis (3) prediction is also based on agency theory since incentive compensation (assuming it is optimally designed) is expected to mitigate agency costs (between managers and owners) and help align senior management’s (i.e., the CEO) goals and interests with shareholders and the board of directors. The higher the incentive compensation of the CEO, the lower the agency costs and the more effective are the corporate governance mechanisms including risk disclosure.

3. DATA AND METHODOLOGY

To examine the nature of the linkages between corporate governance mechanisms and risk disclosure empirically, a sample of the largest Canadian companies represented by the TSX/S&P firms in 2002 is used in the current study with a focus on voluntary risk management disclosure, i.e., risk information disclosed over and above the mandatory requirements and controlling for industry nature. Risk management as a full process is internal to the firm’s operations and is usually considered proprietary information. Therefore, only part of the risk management process is observable to outsiders through public disclosure (both mandatory and voluntary-type of disclosures) which potentially hinders our efforts to study the systematic relationships between corporate governance mechanisms and actual risk management. Given this limitation, the empirical results should be carefully interpreted with caution and not to confound risk management strategies with risk management disclosures.

A detailed content analysis (e.g., Milne and Adler, 1999) of risk and risk management disclosures by this sample’s firms in their annual reports (both in the notes to the financial statements and in the MD&A sections) was conducted to assess the volume and frequency of risk disclosures in the time period under study. Content analysis is suitable for assessing and measuring the volume, intensity and consistency of disclosures particularly when the information disclosed is qualitative in nature which is the case for most risk management disclosures (e.g., Lajili and Zeghal, 2005). Following previous content analysis research (e.g., Milne and Adler, 1999) a graduate student familiar with content analysis procedures was instructed to code the risk information in the annual reports and identify the categories reported by marking on the worksheet the number of words in each risk-related sentence and for each risk category where the word “risk” appeared in the annual report. Corporate governance data was collected for the same study sample and time period using the proxy circular disclosures. Other sample firms’ characteristics were also collected using the Compustat database.

4. Results And Discussion

4.1 Descriptive and content analyses

The study sample comprised 225 firms trading on the TSX in 2002 representing the largest Canadian public companies with average total assets of $13 billion. The sample has a higher proportion of firms in the manufacturing sector (about 40% of the total sample) followed by the mining and construction sector (about 18% of the total sample). Table (1) gives more details about the study sample characteristics in terms of the corporate governance attributes and risk management disclosures. As shown in table (1), the financial services industry has the highest number of board members with an average of thirteen and a median of fourteen members, and the mining/construction sector has the smallest board size with an average of eight members. The degree of board independence in strict terms (i.e., where board members are not identified as company insiders through direct employment by the company) appears to be relatively high in the sample exceeding 74% of board membership on average with the highest independence attributed to the financial services sector (about 81%) and the lowest shown for both the mining/construction and the trade sectors. Most companies represented in the sample also have an average of three to four different committees as shown on table (1). Results not tabulated for ease of presentation show that the most common board committees are the audit committee (99% of the sample), the governance committee (81% of the sample), the compensation committee (59% of the sample), and the “environment, health and safety” committee (27% of the sample). Only 9% of the sample firms have a “risk committee” and most of those firms belong to the financial services, transportation and communication, and manufacturing sectors, respectively.

Table 1.

Corporate Governance and Risk Disclosure: Sample Descriptive Statistics

---------------------------------------------------

Insert Table 1 about here

--------------------------------------------------

In contrast with the uniform distribution of the board attributes across sectors in the TSX sample, table (1) shows that the corporate governance dimensions of ownership, control and executive compensation are widely dispersed and exhibit a significantly higher variability across the companies and sectors represented in the sample. This could be partly attributed to the lack of clear guidance or regulations with regards to these corporate governance mechanisms in the wake of the recent accounting scandals in North America (e.g., Enron, World Com, Nortel Networks,…etc). For example, the fraction of controlling votes varies widely across firms and sectors ranging from as low as 0% to almost 100% for some firms in the sample and the average control vote proportion ranges from about 11% in the manufacturing sector to about 38% in the transportation/communication sector. CEO incentive compensation also shows high dispersion ranging from about $100,000 to about $ 2,885,000 across the firms and sectors in the sample. Similarly, CEOs of the study sample own stocks and options in their companies ranging from 2,200,000 to zero options and stock. Finally, Panel (B) of table ) shows that Canadian publicly traded firms disclose both financial and non-financial types of risk information thus consistent with the enterprise risk management (ERM) conceptual framework (e.g., COSO, 2004).

Table (2) further summarizes the content analysis results and highlighting the predominantly qualitative risk disclosures as reported by the sample firms. It shows the degree of risk exposure, as captured by the likelihood of occurrence of the uncertain event and its potential consequences for the total sample and also by sector in panel (B) of the table. Based on the qualitative risk disclosures provided by the sample firms in their annual reports which were then coded to show a rated scale from 1 to 5 (see footnote to table 2), results reveal that most TSX firms in 2002 recognize their economic exposure to more than one risk factor or category and seem to follow an integrated or enterprise risk management framework (e.g., Beasley et al., 2005, Miller, 1998). For example, 191 firms in the sample report that they are relatively highly exposed to operational risks such as technical failures and loss of key employees among others (e.g., Lajili and Zeghal, 2005) rating the likelihood of such risks occurring at 4.1 on average. The industry analysis further highlights that the “services” sector faces the highest exposure to operational risks (3.95 out of 5) followed by the “financial services” sector (3.89) and the “mining” and “transportation” sectors respectively (3.83).

Table 2.

Risk Assessment and Analysis

---------------------------------------------------

Insert Table 2 about here

--------------------------------------------------

Although the perceived likelihood of risky events or risk factors seems to be higher for some non-financial risk types (e.g., operational risk, government regulation risk, competitive risk), the impact of these risk factors appears to be less severe than financial risks such as interest rate and credit risk according to table (2). It is not clear whether this is attributed to a well-defined risk response plan and strategy followed by the sample firms to control such non-financial types of risks, or if the potential impacts of those risks on firm performance are under-estimated or poorly understood. More research is needed in the future to clarify such issues. Furthermore, the qualitative risk assessment and analysis as disclosed by the sample firms and summarized in table (2) offer interesting insights as to the willingness of some firms to publicly communicate risk information to their stakeholders, however this form of risk disclosure might be limited by the lack of quantification of the risk impacts on firm profitability and more in-depth risk analysis such as the “value-at-risk” or other risk assessment methodologies (e.g., Linsmeir et al., 2002) which is the subject of ongoing research.

4.2 Multivariate analysis

To further investigate the relationships between corporate governance mechanisms and risk disclosure and test the study’s hypotheses, both logistic and multiple regression models are developed and estimated for the study sample firms. Table (3) gives the Pearson correlation coefficients for some of the key study’s variables.

Table 3.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients (p-values)

---------------------------------------------------

Insert Table 3 about here

--------------------------------------------------

As shown in table (3), corporate governance attributes such as board size and board independence are significantly positively correlated. The control ownership variable is positively correlated with both board size and board independence but the correlation is only statistically significant for the board size variable. To distinguish between CEO incentive compensation and base compensation which is more competitively determined on the labour markets for executives, CEO total compensation is broken down into three different components, namely the base salary, bonus pay, and the number of stocks and options held by the CEO. While CEO base salary is significantly and positively correlated with almost all other corporate governance variables, “CEO stocks and options” correlation coefficient with those same variables has the expected sign (positive except for the control ownership variable) but is not statistically significant. Later in the regression analysis, bonus pay is added to other long-term cash incentive compensation to more fully capture all components of CEO incentive compensation. Firm size as measured by total sales is positively and significantly correlated with almost all corporate governance variables and is thus introduced as a control variable in the regression. Table 4 summarizes the logistic regression results to test the study’s hypotheses and help explain and predict corporate risk disclosure intensity based on corporate governance attributes and mechanisms, namely board size, board independence, the fraction of controlling votes, and CEO compensation while controlling for firm size and industry type. Given the high correlations between some corporate governance variables included in this study as shown in table (3), these are alternatively included in the logistic regression. The dependent variable in the logistic model estimated in table (4) is set to 1 if the company outperforms its industry peers in disclosing non-financial risk-type information, and 0 otherwise based on the average non-financial risk disclosures per industry as shown in table (1). Since most financial risk disclosures are mandated by the regulatory bodies in North-America as discussed in section (1) of this paper, non-financial type of risk information is generally disclosed on a voluntary and discretionary basis in Canada in particular. By comparing each company’s disclosure intensity with respect to its peers in its industry group, we effectively control for industry differences across the sample firms and also focus our attention on non-financial more voluntary-type of risk disclosures which might potentially drive stakeholder decision-making.

Table 4.

Risk Disclosure and Corporate Governance Logistic Regression Results

---------------------------------------------------

Insert Table 4 about here

--------------------------------------------------

The logistic regression results presented in table (4) seem to partly support this study’s hypotheses. Board independence is positively and significantly related to the intensity and consistency of risk disclosure thus lending support to H1 in this study and also suggesting the Sarbanes Oxley independence requirement is supported by the data in this case. The higher the proportion of independent board members, the greater the likelihood of high risk disclosure, other things being the same. This finding is important as various regulatory and advisory bodies in North America (including the SEC in the US and the CICA in Canada) have all recommended high board independence as a main feature of effective and good corporate governance. However, other relevant corporate governance mechanisms have received less regulatory attention such as minority control ownership structures and CEO incentive compensation and research dealing with such important governance mechanisms is ongoing (e.g., Coombs and Gilley (2005); Klein, Shapiro and Young (2005)) . As shown in table (4), and consistent with hypothesis (2), the fraction of controlling vote variable is negatively but not significantly related to voluntary risk disclosure intensity. The higher the fraction of controlling vote exhibited by the firm in the sample, the less likely this firm will be a relatively high risk discloser. This result is robust to various model specifications including those not shown in table (4) for ease of presentation. These results suggest that the ownership and control structure is a potentially relevant corporate governance variable and thus should not be overlooked or under-estimated in future research and also regulatory discussions particularly in countries where such structures are commonly observed such as in Canada and some countries in Europe (e.g., Cronqvist and Nilsson 2003, Laporta et al. 1999). Minority control ownership structures could potentially increase agency costs and ultimately lead to ineffective corporate governance. However, it is not clear whether the source of minority vote control has any differential impact on corporate governance. We conducted further regressions including dummy variables denoting whether the minority voting control is held by a founder family, a corporation or a financial institution respectively. Results not shown on table (4) for ease of presentation show that if minority vote control is held by a corporation, it increases significantly the likelihood of high risk disclosure whereas if a founder family of a financial institution holds minority voting control, it negatively but not significantly impacts on voluntary risk disclosure intensity. Future research could further investigate this result and shed more light on the nature of information asymmetries and associated agency costs between minority control shareholders and other common shareholders and impacts on governance mechanisms. CEO incentive compensation whether captured by the number of options and shares granted to the CEO under long-term incentive programs or as additional incentive compensation in terms of bonus pay and other long-term compensation, shows a positive but not significant impact on voluntary risk disclosure intensity as shown on table (4). Thus only a weak support for agency theory with respect to CEO incentive compensation is documented in this study. Finally, firm size is positively and significantly associated with increased risk disclosure which is expected as bigger companies are usually exposed to more risks and are usually operating in various business segments and globally as well. Further, the firm size variable controls for the total disclosure intensity and behavior as larger firms are more politically visible, have economies of scale in processing information and are thus expected to disclose more corporate information voluntarily, other things being the same.

Table (5) further tests the study’s hypotheses using multiple regression techniques and reports the results for the sample firms. In this case, the number of non-financial risk sentences disclosed both in the notes and the MD&A section of the company’s annual report is the dependent variable. Industry type is now controlled for in the regression model by including dummy variables for each 1-digit sector included in the sample (TSX 230, 2002). The results are in general consistent with table (4) logistic regression results. Board independence and firm size and positively and significantly related to risk disclosure intensity whereas minority voting control is negatively but not significantly related to risk disclosure. Mining companies significantly disclose more non-financial risk information and this could be attributed to the degree of regulatory control imposed upon this particular industry given the nature of its business operations and environmental impacts and other potential risk factors. An interesting result shown on table (5) is the negative relationship between CEO compensation and risk disclosure intensity which is significant at 10% for the “stocks and options” incentive compensation variable. This result might suggest that granting more options and stocks to the CEO might have negative impacts on corporate governance by entrenching top management in this case and leading to less transparency and disclosure potentially increasing agency costs rather than reducing them. Further research is needed to clarify the links between CEO incentive compensation and risk management and disclosure in the future.

Table 5.

Risk Disclosure and Corporate Governance Logistic Regression Results

---------------------------------------------------

Insert Table 5 about here

--------------------------------------------------

5. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The current paper explores the potential linkages between corporate governance and corporate risk disclosure intensity. Corporate governance is approached from two dimensions: the characteristics of the board of directors associated with effective governance mechanisms following prior research and recent regulations (e.g., SOX, CICA) and an agency theory-based approach to corporate governance in terms of the extent of the agency costs involved in governance structures. The empirical analysis dealing with Canadian publicly-traded companies (TSX 230 in 2002) seems to support the existence and significance of such linkages. The results lend general support to some of the recent regulations (e.g., SOX, CICA) and also to agency theory predictions (e.g., Cronqvist and Nilsson 2003). In addition to documenting a fairly good amount of predominantly qualitative information about risk exposure and risk management as disclosed by TSX 230 firms, thus consistent with the Enterprise Risk Management general framework (COSO, 2004), this study further shows that corporate risk disclosure intensity is closely related to some key corporate governance variables. More specifically, regression results show that Canadian public companies are more likely to disclose more risk information if their boards of directors have more independent members thus lending support to recent regulatory changes and recommendations (e.g., SOX, CICA). Another important finding is the consistent negative although not significant relationship between the degree of controlling vote ownership structures and risk disclosure, suggesting that ownership and control structures are perhaps among the key corporate governance variables that would impact risk disclosure intensity and transparency in the future. Another governance variable that warrants more research attention with respect to its potential impacts on risk management and disclosure in the future is CEO incentive compensation. Mixed results were found in this study. Future research could further elaborate on executive incentive compensation and its impacts on overall governance and risk management and disclosure behavior. Further, risk disclosure quality and not just intensity could be a more relevant research undertaking in the future where risk disclosures are used to infer the quality and effectiveness of the risk management strategies and overall corporate governance. Collectively, these results suggest that enterprise risk management as a strategically designed process and a performance control tool is inherently intertwined with corporate governance mechanisms and thus should be implemented following an integrated approach encompassing all possible aspects of firm’s operational as well as organizational and governance-oriented characteristics. From a public policy perspective, regulatory bodies and agencies in North America and around the world could further examine the impact of different ownership and decision control structures as well as CEO power and incentive compensation, among others, on risk disclosure quality, transparency, and corporate governance effectiveness in general. The Enterprise Risk Management framework seems to be well suited for providing a potentially sound, comprehensive and hopefully verifiable (audit-friendly) basis for integrating all the possible facets of risks to which companies are exposed and also ensuring that those risks are fairly communicated to all stakeholders. More research is needed to guide management, boards and regulatory bodies as well as information users in effectively measuring risk and tracking management performance records in managing all kinds of risks and business uncertainties.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research support of the CGA Accounting Research Centre and the Telfer School of Management at the University of Ottawa are gratefully acknowledged.

Telfer School of Management, University of Ottawa55 Laurier East, Ottawa, Ontario K1N 6N5, Telephone: (613) 562-5800 ext. 4736, Fax: (613) 562-5164, Email: lajili@telfer.uottawa.ca, and/or Lajili@uottawa.ca. As corporate risk management continues to evolve globally to embrace several aspects of business operations and activities, corporate governance and corporate risk management are increasingly intertwined thus highlighting the importance of interdependencies and mutual impacts of corporate governance choice on overall risk management strategies and disclosures. In other words, enterprise-wide risk management is a natural and key component of corporate governance. While several regulatory changes have been implemented recently (e.g., Sarbanes-Oxley act) much of the relevant information disclosed by corporations remains voluntary to a great extent. Risk disclosure is no exception and recent governance regulations and guidance seem to offer research opportunities to first document firms’ responses to these regulations and then examine any changes in disclosure behavior. This paper provides a primary step towards closing this research gap by empirically investigating the nature of the linkages potentially existing between corporate governance and risk management disclosure for a sample of Canadian publicly-listed companies. The paper highlights the importance of considering several dimensions of corporate governance simultaneously to evaluate the effectiveness of corporate governance structures and examine in a more comprehensive way accounting disclosures related to governance and risk disclosure issues within a unified framework of enterprise-wide risk management. Results from this empirical study reveal that firms are more likely to disclose risk management information over and above the mandatory requirements, if their boards of directors have more independent members, thus consistent with the Sarbanes-Oxley board independence requirements. Firm size and industry nature also significantly impact the likelihood of increased risk disclosure by sample firms. Further, a negative relationship between the degree of controlling vote ownership structures and risk disclosure is documented, whereas the CEO incentive compensation components show some mixed results as to their impact on risk disclosure behavior as explained in more detail below.

The paper proceeds as follows: Section 1 briefly reviews the regulatory framework for risk management and corporate governance disclosure in North America. Section 2 discusses some prior related research and presents this paper’s research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data and methodology for the empirical analysis, while Section 4 reports and discusses the empirical findings. Section 5 concludes with some policy implications and suggestions for future research.

REFERENCES

- R. B. Adams, H. Almeida, and D. Ferreira. “Powerful CEOs and Their Impact on Corporate Performance.” Review of Financial Studies 18, 4 (2005): 1403–1432. [Google Scholar]

- M. S. Beasley, and S. Salterio. “The Relationship between Board Characteristics and Voluntary Improvements in the Capability of Audit Committees to Monitor.” Contemporary Accounting Research 18, 4 (2001): 539–570. [Google Scholar]

- M. S. Beasley, R. Clune, and D. R. Hermanson. “Enterprise Risk Management: An Empirical Analysis of Factors Associated with the Extent of Implementation.” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 24 (2005): 512–531. [Google Scholar]

- J. C. Bedard, and K. M. Johnstone. “Earnings Manipulation Risk, Corporate Governance Risk, and Auditors’ Planning and Pricing Decisions.” The Accounting Review 79, 2 (2004): 277–304. [Google Scholar]

- G. J. Benston, and A. L. Hartgraves. “Enron: What happened and what we can learn from it.” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 2002, 105–127. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA). “Guidance for Directors: Governance Processes for Control.” 1995 (December). [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA) (2000). “Guidance for Directors: Dealing with Risk in the Boardroom.” 2000 (April). [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA). “Beyond Compliance: Building a Governance Culture, Final report.” (November) 2001. Available at: http://jointcomgov.com. [Google Scholar]

- J. Cohen, G. Krishnamoorthy, and A. M. Wright. “Corporate Governance and The Audit Process.” Contemporary Accounting Research 19, 4 (2002): 573–594. [Google Scholar]

- Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). “Enterprise Risk Management- Integrated Framework.” COSO, New York, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- J. E. Coombs, and M. Gilley. “Stakeholder Management as a Predictor of CEO Compensation: Main Effects and Interactions with Financial Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 26 (2005): 827–840. [Google Scholar]

- J. Core, and W. Guay. “The Use of Equity Grants to Manage Optimal Equity Incentive Levels.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 28 (1999): 151–184. [Google Scholar]

- H. Cronqvist, and M. Nilsson. “Agency Costs of Controlling Minority Shareholders.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 38, 4 (2003): 695–719. [Google Scholar]

- P. A. Gompers, J. L. Ishii, and A. Metrick. “Corporate Governance and Equity Prices.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 118, 1 (2003): 107–155. [Google Scholar]

- O. Hart. “Incomplete Contracts and the Theory of the Firm.” Journal of Law 4 (1988): 119–139. [Google Scholar]

- M. Jensen, and W. Meckling. “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure.” Journal of Financial Economics 3 (1976): 305–360. [Google Scholar]

- M. C. Jensen, and K. J. Murphy. “Performance Pay and Top-Management Incentives.” Journal of Political Economy 98 (1990): 225–264. [Google Scholar]

- Peter Klein, Shapiro Daniel, and Jeff Young. “Corporate governance, Family Ownership and Firm Value: the Canadian Evidence.” Corporate Governance: an International Journal 13, 6 (2005): 769–784. [Google Scholar]

- K. Lajili, and D. Zéghal. “A Content Analysis of Risk Management Disclosures in Canadian Annual Reports.” Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 2005, 22, 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- R. Laporta, F. Lopez-de-Silanes, F. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. “Corporate Ownership around the World.” Journal of Finance 54 (1999): 471–517. [Google Scholar]

- T. J. Linsmeir, D. B. Thornton, M. Venkatachalam, and M. Welker. “The Effect of Mandated Market Risk Disclosures on Trading Volume Sensitivity to Interest Rate, Exchange Rate, and Commodity Price Movements.” Accounting Review 77, 2 (2002): 343–377. [Google Scholar]

- J. T. Mahoney. “The Choice of Organizational Form: Vertical Financial Ownership versus Other Methods of Vertical Integration.” Strategic Management Journal 13 (1992): 559–584. [Google Scholar]

- K. D. Miller. “Economic Exposure and Integrated Risk Management.” Strategic Management Journal 19, 5 (1998): 497–514. [Google Scholar]

- M. J. Milne, and R. W. Adler. “Exploring the Reliability of Social and Environmental Disclosures Content Analysis, Accounting.” Auditing and Accountability Journal 12, 2 (1999): 237–256. [Google Scholar]

- “Sarbanes-Oxley Act, of 2002. (SOX).” In Public Law No. 107-204; Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2002.

- Oliver, E. Williamson. “The Mechanisms of Governance.” New York: The Free Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]