The Effects of Globalization and Foreign Direct Investment on the Economic Growth of South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Literature

2.2. Empirical Literature

2.2.1. Globalization and Economic Growth

2.2.2. FDI and Economic Growth

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

3.2. Model Specification

3.3. Estimation Methods

3.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.3.2. Correlation Analysis

3.3.3. Stationarity Test

3.3.4. Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Bounds Test

3.3.5. Granger Causality Test

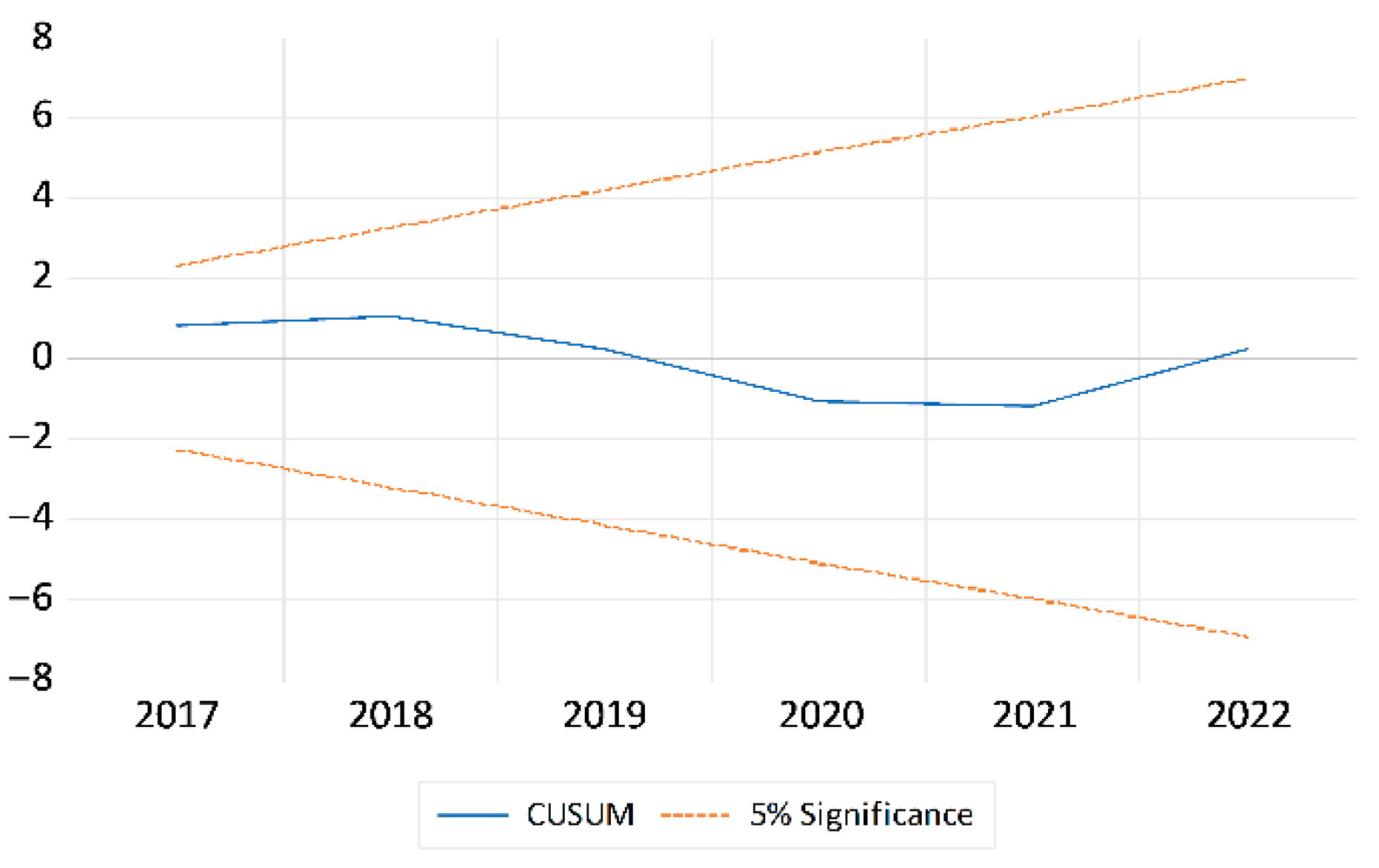

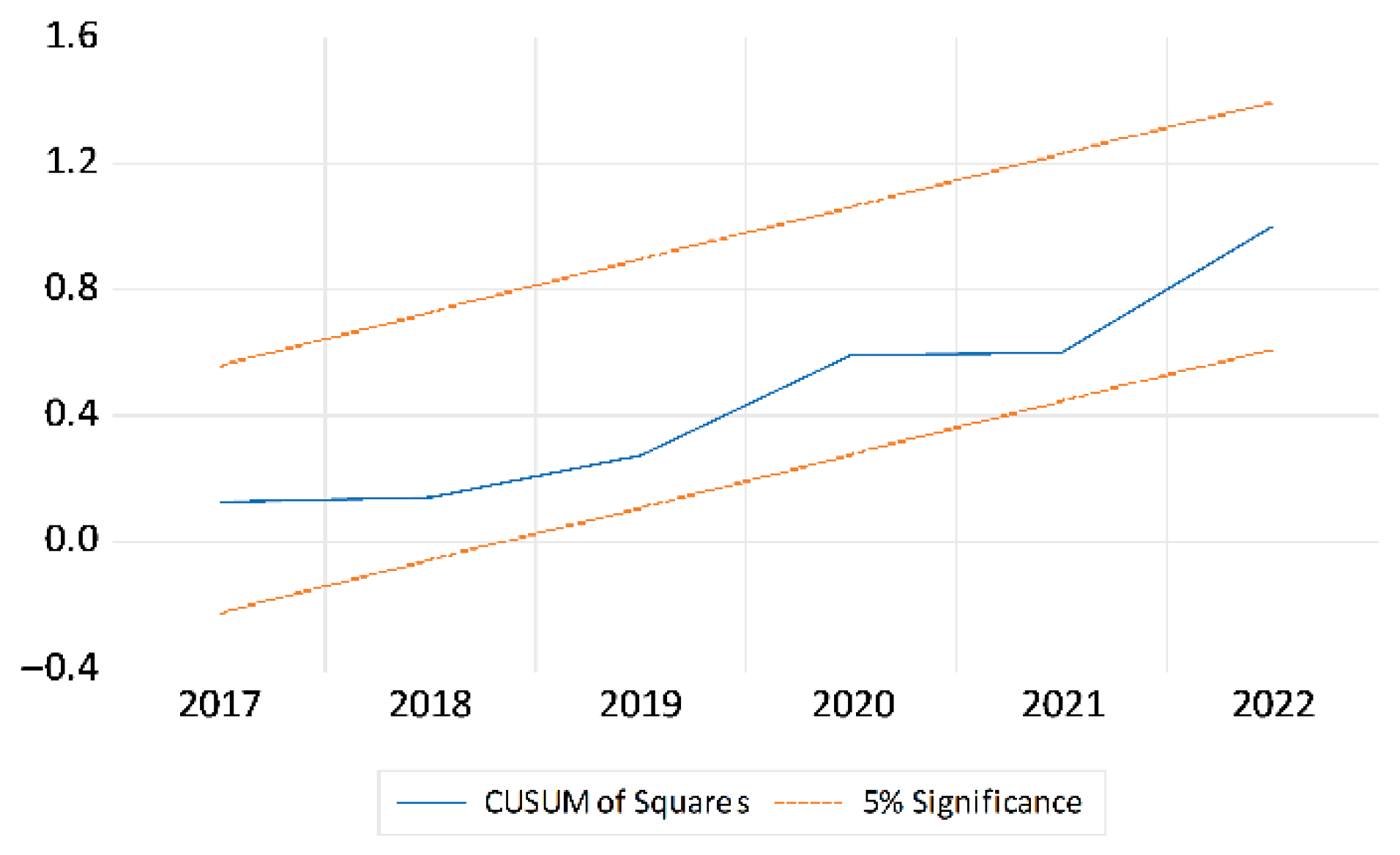

3.3.6. Diagnostic and Stability Tests

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistic Outcomes

4.2. Correlation Analysis Outcomes

4.3. Stationarity Outcomes

4.4. ARDL Bounds Outcomes

4.5. Pairwise Granger Causality Outcomes

4.6. Diagnostic and Stability Outcomes

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abidemi, A. K., Bright, A. F., & Musa, A. (2023). Classification of some test of normality techniques into UMP and LMP using monte Carlo simulation technique. Mathematics Letters, 9(1), 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M., Kuldasheva, Z., Nasriddinov, F., Balbaa, M. E., & Fahlevi, M. (2023). Is achieving environmental sustainability dependent on information communication technology and globalization? Evidence from selected OECD countries. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 31, 103178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N., & Hussain, H. (2017). Impact of foreign direct investment on the economic growth of Pakistan. American Journal of Economics, 7(4), 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Apostol, M., Enriquez, H. A., & Sumaway, O. (2022). Innovation factors and its effect on the GDP per capita of selected ASEAN countries: An application of Paul Romer’s endogenous growth theory. International Journal of Social and Management Studies, 3(2), 119–139. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, R. P., & Robinson, W. I. (Eds.). (2005). Critical globalization studies. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Mim, S., Hedi, A., & Ben Ali, M. S. (2022). Industrialization, FDI and absorptive capacities: Evidence from African Countries. Economic Change and Restructuring, 55(3), 1739–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J., & Lee, J. W. (1998). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics, 45(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, S. (2025). Long live globalization: Geopolitical shocks and international trade. International Economics and Economic Policy, 22(2), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplyuk, V. Z., Akhmedov, F. N., Zeitoun, M. S., Abueva, M. M. S., & Al Humssi, A. S. (2022). The impact of FDI on Algeria’s economic growth. In Geo-economy of the future: Sustainable agriculture and alternative energy (pp. 285–295). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D. (2000). City, space and globalisation: An international perspective. Journal of Urban Design, 5(1), 86. [Google Scholar]

- Dabwor, D. T., Iorember, P. T., & Yusuf Danjuma, S. (2022). Stock market returns, globalization and economic growth in Nigeria: Evidence from volatility and cointegrating analyses. Journal of Public Affairs, 22(2), e2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H., Abdulrahman, B. M. A., Ahmed, S. A. K., Abdallah, A. E. Y., Elkarim, S. H. E. H., Sahal, M. S. G., Nureldeen, W., Mobarak, W., & Elshaabany, M. M. (2024). The dynamic relationships between oil products consumption and economic growth in Saudi Arabia: Using ARDL cointegration and Toda-Yamamoto Granger causality analysis. Energy Strategy Reviews, 54, 101470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(366a), 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, A. (2006a). Does globalization affect growth? Evidence from a new index of globalization. Applied Economics, 38(10), 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, A. (2006b). The influence of globalization on taxes and social policy: An empirical analysis for OECD countries. European Journal of Political Economy, 22(1), 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, A., Sturm, J. E., & Ursprung, H. W. (2008). The impact of globalization on the composition of government expenditures: Evidence from panel data. Public Choice, 134, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazaalloh, A. M. (2024). FDI and economic growth in Indonesia: A provincial and sectoral analysis. Journal of Economic Structures, 13(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, D. M., & Ruffin, R. J. (1993). What determines economic growth. Economic Review, 2, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, C. W. J. (2008). Spurious regressions. In The new Palgrave dictionary of economics. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y. (2025). Mirror, reflection, and prospect: South Korea’s integration into economic globalization—Process, experiences, and implications for China. Journal of Current Social Issues Studies, 2(5), 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jijian, Z., Twum, A. K., Agyemang, A. O., Edziah, B. K., & Ayamba, E. C. (2021). Empirical study on the impact of international trade and foreign direct investment on carbon emission for belt and road countries. Energy Reports, 7, 7591–7600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S. (2000). The club model of multilateral cooperation and problems of democratic legitimacy. In Power and governance in a partially globalized world (pp. 219–244). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kgomo, D. M., & Zhanje, S. (2024). Foreign direct investment, trade and economic growth: A case study of South Africa. International Journal of Research in Business & Social Science, 13(7), 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, M. A. (2020). The role of ICT infrastructure, innovation and globalization on economic growth in OECD countries, 1996–2017. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 11(2), 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., & Tanna, S. (2019). The impact of foreign direct investment on productivity: New evidence for developing countries. Economic Modelling, 80, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Liu, X. (2005). Foreign direct investment and economic growth: An increasingly endogenous relationship. World Development, 33(3), 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, S. S., & Somwaru, A. (2004). Impact of foreign direct investment and trade on economic growth: Evidence from developing countries. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 86(3), 795–801. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3697825 (accessed on 22 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Motoyama, Y. (2025). A dynamic optimization model considering cost and speed in the cobb-Douglas production function. Decision Analytics Journal, 14, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, B., & Khan, M. K. (2021). Foreign direct investment inflow, economic growth, energy consumption, globalization, and carbon dioxide emission around the world. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(39), 55643–55654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natufe, O. K., & Evbayiro-Osagie, E. I. (2023). Credit risk management and the financial performance of deposit money banks: Some new evidence. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(7), 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, A., & Ahmad, E. (2018). Driving factors of globalization: An empirical analysis for the developed and developing countries. Business & Economic Review, 10(1), 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. H. (2020). Impact of foreign direct investment and international trade on economic growth: Empirical study in Vietnam. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(3), 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P. (2000). A virtuous circle: Political communications in post-industrial societies. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nye, J. S., & Donahue, J. D. (2000). Governance in a globalizing world (pp. 45–71). Visions of Governance for the 21st Century. Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Okwu, A. T., Oseni, I. O., & Obiakor, R. T. (2020). Does foreign direct investment enhance economic growth? Evidence from 30 leading global economies. Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies, 12(2), 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegkas, P. (2018). The effect of government debt and other determinants on economic growth: The Greek experience. Economies, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, P. (2017). Indian manufacturing industry in the Era of globalization: A Cobb-Douglas production function analysis. Indian Journal of Economics and Development, 5(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, P. C., & Perron, P. (1988). Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika, 75(2), 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilinkiene, V. (2016). Trade openness, economic growth and competitiveness. The case of the central and eastern European countries. Inzinerine Ekonomika-Engineering Economics, 27(2), 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A. (2023). The dynamic nexus between economic growth, renewable energy use, urbanization, industrialization, tourism, agricultural productivity, forest area, and carbon dioxide emissions in the Philippines. Energy Nexus, 9, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, R. (1992). Globality, global culture, and images of world order. In Social change and modernity (pp. 395–411). University of California Press. Available online: http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6000078s/ (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Robinson, W. I. (2007). Theories of globalization. In The Blackwell companion to globalization (pp. 125–143). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. (2007). One economics, many recipes: Globalization, institutions, and economic growth. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94(5), 1002–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), S71–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P. M. (1994). The origins of endogenous growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M., Kannaiah, D., Yahya Khan, G., Shabbir, M. S., Bilal, K., & Zamir, A. (2023). Does sustainable environmental agenda matter? The role of globalization toward energy consumption, economic growth, and carbon dioxide emissions in South Asian countries. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 25(1), 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A., Khan, M. A., Sarwar, Z., & Khan, W. (2021). Financial development, human capital and its impact on economic growth of emerging countries. Asian Journal of Economics and Banking, 5(1), 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilirò, D. (2019). Public debt and growth in Italy: Analysis and policy proposals. International Journal of Business Management and Economic Research, 10(5), 1695–1702. [Google Scholar]

- Shittu, W. O., Yusuf, H. A., El Moctar El Houssein, A., & Hassan, S. (2020). The impacts of foreign direct investment and globalisation on economic growth in West Africa: Examining the role of political governance. Journal of Economic Studies, 47(7), 1733–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, R. G., & Wang, K. (2019). The Cobb-Douglas production function revisited. In International conference on applied mathematics, modeling and computational science (pp. 725–734). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M., Jan, A. A., Shah, S. Q. A., Alam, M. B., Afridi, M. A., Tariq, Y. B., & Bashir, M. F. (2020). Foreign inflows and economic growth in Pakistan: Some new insights. Journal of Chinese Economic and Foreign Trade Studies, 13(3), 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thach, N. N. (2020). Endogenous economic growth: The Arrow-romer theory and a test on Vietnamese economy. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, 17(1), 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trushkina, N. (2019). Development of the information economy under the conditions of global economic transformations: Features, factors and prospects. Virtual Economics, 2(4), 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsimisaraka, R. S. M., Xiang, L., Andrianarivo, A. R. N. A., Josoa, E. Z., Khan, N., Hanif, M. S., & Limongi, R. (2023). Impact of financial inclusion, globalization, renewable energy, ICT, and economic growth on CO2 emission in OBOR countries. Sustainability, 15(8), 6534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utouh, H., & Tile, A. (2023). The nexus between foreign direct investment and nominal exchange rate, real GDP, and capital stock in Tanzania. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum. Oeconomia, 22(1), 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utouh, H. M., & Kitole, F. A. (2024). Forecasting effects of foreign direct investment on industrialization towards realization of the Tanzania development vision 2025. Cogent Economics & Finance, 12(1), 2376947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimer, A., & Geda, A. (2024). A two-edged sword: The impact of public debt on economic growth—The case of Ethiopia. Journal of Applied Economics, 27(1), 2398908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y. H., Chang, K., & Lee, C. H. (2014). The impact of globalization on economic growth. Romanian Journal of Economic Forecasting, 17(2), 25–34. [Google Scholar]

| GDP | EG | SG | PG | FDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 2.282432 | 54.29913 | 57.21946 | 84.42479 | 1.707904 |

| Median | 2.485468 | 55.10880 | 58.38375 | 87.03045 | 1.064922 |

| Maximum | 5.603806 | 56.77578 | 64.50203 | 88.78750 | 9.660265 |

| Minimum | −6.168918 | 42.83302 | 46.89833 | 62.92066 | 0.205126 |

| Std. Dev. | 2.498752 | 3.121094 | 6.445045 | 6.202791 | 2.003242 |

| Skewness | −1.486435 | −2.593214 | −0.372588 | −2.042371 | 2.835439 |

| Kurtosis | 6.391188 | 9.412616 | 1.620898 | 6.966294 | 11.33980 |

| Jarque–Bera | 21.18554 | 70.85487 | 2.559596 | 33.76730 | 105.9491 |

| Probability | 0.000025 | 0.000000 | 0.278093 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| GDP | EG | SG | PG | FDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | 1 | 0.684304719066333 | 0.2067838396259611 | −0.1162302097486438 | 0.1854778738703447 |

| EG | 0.684304719066333 | 1 | 0.382512231466979 | −0.3389367069193484 | −0.2756592046858194 |

| SG | 0.2067838396259611 | 0.382512231466979 | 1 | 0.06710024620488241 | −0.478841140684206 |

| PG | −0.1162302097486438 | −0.3389367069193484 | 0.06710024620488241 | 1 | 0.06084438119746366 |

| FDI | 0.1854778738703447 | −0.2756592046858194 | −0.478841140684206 | 0.06084438119746366 | 1 |

| Level, I(0) | First Difference, I(1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model Specification | ADF Test Statistic | PP Test Statistic | ADF Test Statistic | PP Test Statistic |

| GDP | Intercept | −3.928384 *** | −3.922439 *** | ||

| Trend and intercept | −3.887106 ** | −5.095355 *** | |||

| EG | Intercept | −7.434145 *** | −7.968747 *** | ||

| Trend and intercept | −7.512395 *** | −6.684237 *** | |||

| SG | Intercept | −1.446228 | −1.486405 | −4.684442 *** | −4.699117 *** |

| Trend and intercept | 0.403939 | 0.089354 | −5.418640 *** | −5.537796 *** | |

| PG | Intercept | −9.007075 *** | −9.387655 *** | ||

| Trend and intercept | −3.704694 ** | −7.443643 *** | |||

| FDI | Intercept | −4.734383 *** | −9.883640 *** | ||

| Trend and intercept | −4.809780 *** | −10.24407 *** | |||

| F-Statistic: 6.620790 | |||||

| K: 4 | |||||

| 10% | 5% | 1% | |||

| 1.900 | 3.010 | 2.260 | 3.480 | 3.070 | 4.440 |

| LONG-RUN | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Probability |

| EG | 1.269232 | 0.494413 | 2.567146 | 0.0194 ** |

| SG | 0.162452 | 0.278528 | 0.583253 | 0.5670 |

| PG | −0.947091 | 0.425053 | −2.228174 | 0.0389 ** |

| FDI | 1.469641 | 0.922679 | 1.592797 | 0.1286 |

| SHORT-RUN | ||||

| D(EG) | 1.305165 | 0.216392 | 6.031483 | 0.0001 *** |

| D(SG) | 0.539466 | 0.370725 | 1.455165 | 0.1763 |

| D(PG) | −1.197494 | 0.361277 | −3.314611 | 0.0078 *** |

| D(FDI) | 0.830651 | 0.100216 | 8.288627 | 0.0000 *** |

| SPEED OF ADJUSTMENT | ||||

| ECT | −0.943755 | 0.127056 | −7.427870 | 0.0000 *** |

| Null Hypothesis: | Obs | F-Statistic | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| EG does not Granger-cause GDP | 22 | 0.71420 | 0.5586 |

| GDP does not Granger-cause EG | 0.43410 | 0.7317 | |

| SG does not Granger-cause GDP | 22 | 3.78077 | 0.0334 ** |

| GDP does not Granger-cause SG | 0.30237 | 0.8232 | |

| PG does not Granger-cause GDP | 22 | 1.54273 | 0.2445 |

| GDP does not Granger-cause PG | 0.54396 | 0.6596 | |

| FDI does not Granger-cause GDP | 22 | 0.44622 | 0.7236 |

| GDP does not Granger-cause FDI | 1.57017 | 0.2380 | |

| SG does not Granger-cause EG | 22 | 0.42729 | 0.7364 |

| EG does not Granger-cause SG | 0.97575 | 0.4302 | |

| PG does not Granger-cause EG | 22 | 0.89436 | 0.4668 |

| EG does not Granger-cause PG | 1.63199 | 0.2241 | |

| FDI does not Granger-cause EG | 22 | 1.21127 | 0.3397 |

| EG does not Granger-cause FDI | 0.70910 | 0.5615 | |

| PG does not Granger-cause SG | 22 | 1.84872 | 0.1817 |

| SG does not Granger-cause PG | 0.79229 | 0.5169 | |

| FDI does not Granger-cause SG | 22 | 3.28123 | 0.0503 * |

| SG does not Granger-cause FDI | 1.85790 | 0.1801 | |

| FDI does not Granger-cause PG | 22 | 3.74951 | 0.0343 ** |

| PG does not Granger-cause FDI | 0.37685 | 0.7710 | |

| Estimation Technique | Probability | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jarque–Bera normality test | Normal Distribution | 0.875630 | Accept , there is normal distribution. |

| Breusch–Godfrey Serial Correlation LM Test | No serial correlation up to 2 lags | 0.6439 | Accept , there is no serial correlation. |

| ARCH: Heteroskedasticity Test | No Heteroskedasticity | 0.6826 | Accept , there is no heteroskedasticity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ratombo, N.E.; Kgomo, D.M. The Effects of Globalization and Foreign Direct Investment on the Economic Growth of South Africa. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2026, 19, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010007

Ratombo NE, Kgomo DM. The Effects of Globalization and Foreign Direct Investment on the Economic Growth of South Africa. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2026; 19(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleRatombo, Ndivhuho Eunice, and Dintuku Maggie Kgomo. 2026. "The Effects of Globalization and Foreign Direct Investment on the Economic Growth of South Africa" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 19, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010007

APA StyleRatombo, N. E., & Kgomo, D. M. (2026). The Effects of Globalization and Foreign Direct Investment on the Economic Growth of South Africa. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 19(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010007